At the start of the month, the 35th Bienal de São Paulo – the world’s second oldest after Venice’s, inaugurated in 1951 – opened its doors. Housed in the Oscar Niemeyer-designed Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion in the city’s sprawling Ibirapuera Park, this edition sees the works of 121 participating artists, the majority of which hail from countries with a history as colonial subjects, with a particular focus on Brazil. The event marks one of a number of high points for Brazil’s exponentially booming art world over the past year, drawing the world’s attention to the nation’s incredible artistic heritage and wealth. Other events of note include the 19th edition of SP-Arte, Latin America’s foremost art fair, as well as the currently ongoing Bienal das Amazônias, taking place in Belém.

Another of this year’s highlights for the Brazilian art world took place in May, when Bottega Veneta landed in São Paulo to unveil the latest edition of The Square — the Italian luxury brand’s itinerant cultural exchange series. Chiming with the 10th anniversary of its arrival in the country, it commemorated the legacy of Italian-Brazilian architect, designer and thinker Lina Bo Bardi – a perennial point of reference of current Bottega Veneta creative director Matthieu Blazy – inviting a dynamic coterie of Brazilian artists, curators, thinkers and community leaders to celebrate this seminal cultural figure; contemplating the paths she paved for the generations of Brazilian artists that have followed in her wake.

Under the curatorial remit of esteemed Rio de Janeiro-based curator Mari Stockler, The Square took place in the Casa de Vidro – a Modernist architectural jewel that served as Lina’s private residence until her passing in 1992 – and its sprawling tropical gardens. A collaboration between Mari, Matthieu and the Iguatemi group, the conceptual impetus for the project was Mari’s desire “to find a way to bring the house to life,” she shares, looking to its existing collection of artworks and objects to contemplate “which contemporary and modern artists would Lina have brought into it today?”.

Structured around four thematic pathways, visitors to The Square over the course of its 10-day run found themselves immersed in a series of open dialogues between artists, generations and timestreams; confronted with works by artists that represent the unfathomable breadth of Brazil’s artistic output, from internationally renowned interdisciplinarian Luiz Zerbini to emerging visual artist Raphael Cruz. Among those invited by Mari, three young artists were of particular note: Allan Weber, Davi de Jesus do Nascimento and Gokula Stoffel.

Broaching themes spanning police brutality, the relationship between the human psyche and materiality, spiritual protection and the contemporary Brazilian sociopolitical climate, their work is a testament of the range and artistic richness of an emerging generation of Brazilian artists. Below, the three artists discuss their respective practices, and the significance of being part of Bottega Veneta’s São Paulo iteration of The Square.

Allan Weber

How would you introduce yourself and your practice?

My work is based on my daily life, and my existence within the favela, where I take codes that come from drug trafficking, cultural manifestations like dances and haircuts, and even objects that are only seen in these communities. From there, I deconstruct them, giving them new meanings and concepts, and transforming them into objects, installations, sculptures or even photographs. Anything, really.

What are your main preoccupations and intentions as an artist?

I’ve always thought about who I was going to make art for and where I was going to take my work. I think a lot about the place I came from, where art or the contemporary art market has never been. The favelas in Brazil are incredibly culturally rich: we need artists from the favela, curators from the favela, gallerists from the favela. The favela is a place where, with very little, everyone can do incredible things and everyone is very talented – they seem to have superpowers. If they had access to certain tools I think this would only add to art history and the art market.

My intention has always been to take art to my people – when I went home, my friends would ask me what I was doing for work, and when I said that I was an artist, they thought I was singing trap or asked if I did graffiti. So I needed to show them what I did. Contemporary art, in an institutional sense, wasn’t something they’d been exposed to, so it was all very abstract for them. That’s where I got the brilliant idea of opening an art gallery in my favela, Galeria 5bocas, which is in the middle of Complexo de Israel in Rio. That’s where I was able to exhibit my first works and help people to develop a sense of intimacy with the space and the art. As much as my works had many things and elements from our reality, they were still created with the intention of deconstructing their views.

Tell us a bit about your journey to becoming an artist. What would say were the defining moments that set you on the path that you now follow?

I started working at a very young age due to my family’s financial situation. I worked at McDonald’s, I sold cans, I watched over cars on the street, I helped bricklayers, I was a salesperson, I did illegal things… but one day I went to work in the stock cupboard in a women’s shoe store in Ipanema. It was far from my house, so I spent time in the neighbourhood and on the beach, walking to save time because of the traffic. I ended up at a skate park by the Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, and started going everyday, eventually picking up skateboarding. I made a lot of friends there, and that’s where I had my first contact with cameras. I thought their style was really cool, and I soon bought a camera and started photographing my skater friends and their clothes. At work, I spent a lot of time doing nothing because I got everything done pretty quickly, but there was a newsstand and I was friends with the guy who worked there, so I would borrow the fashion magazines to read upstairs and return them later. When I went back to the favela I also took photos of my friends there, flying kites, playing football, dying their hair, wearing their hats. During that time, I was asked by Zé Tepedino to work with him as a freelancer at Osklen, a fashion brand from Rio. I did a little bit of everything there, but I spent a lot of time on campaign shoots, where I was able to watch great photographers, directors and models work. Beyond Osklen, Zé was also an artist, and he started taking me to art exhibitions. Seeing all this happening up close – the fashion shows, the campaigns and the art – stretched me a lot visually and physically. It gave me a great desire to start producing and expanded my perspective. I saw that there were several possibilities, because where we come from there are few career opportunities, or you become a hustler or a drug dealer.

Within these spaces, while beautiful, I started realising that I didn’t see things that talked about the favela, or that represented me. That’s when I chose to pursue art and bring my reality to this market. Then, the pandemic came, and as I was a freelancer and had no formal connection to Osklen, I had to stop working with Zé. My son had just been born, so I borrowed some money, bought a motorbike started working at iFood [a food delivery service], without even having a license. In the second week, I started to realise that everything was working in a different way, where everyone was in their homes, and delivery drivers were taking risks by taking food to people. There was a problem there, but I saw that it needed to be recorded firsthand – that it wasn’t someone recording the life of a delivery man, but that it was the delivery man himself recording his work. Through these photographs, together with some I’d already taken, I found the courage to show my work and, with the help of friends, to create a book, Existe uma vida inteira que tu não conhece (There is a whole life that you don’t know).

Tell us about the work you exhibited as part of The Square São Paulo. What is its significance?

The photograph I showed is of a friend with a patch-bleached buzz cut, which is very much in fashion in Rio’s favelas. Because of that, though, anyone who leaves the favela with this hairdo is automatically seen as a criminal, and they therefore suffer brutal attacks and prejudice on the streets. My intention in bringing this work to Casa de Vidro was to place and represent favela communities in this space, and to make people see it in a different way — without prejudice or media spin. It’s showing that for these people, just because of the way they have their hair, it’s normal to have police officers come and ask them to put their hands up against the wall, which is why the subject is turned away.

What was the significance of having your work included in the exhibition?

Being able to access these places, and showing that people from the favela can occupy them, too, felt very significant. I want to serve as an inspiration for my children and show them that there are different possibilities; they need to see us happy and well, as they are so used to seeing us in mourning.

Davi de Jesus do Nascimento

How would you introduce yourself and your practice?

When I was born, in 1997, in the north of Minas Gerais, they gave me the same name as my father, Davi de Jesus do Nascimento. I am a Curimatá Barranqueiro born on the banks of the São Francisco River, the watercourse of my life, and was raised among carranqueiros [artisans who craft carrancas, wooden figureheads attached to boats to protect boatmen from river-dwelling evil spirits], fishermen and laundresses. My work is a testament to the affections of riverside ancestry and perceives “quasi-rivers’’ in arid landscapes.

What are your main preoccupations and intentions as an artist?

I have been busy drying the bittersweet waters that run down from my brow to Pirapora, where I grew up. For us – those who were born in the upper-middle reaches of the São Francisco river, and who experience the trauma passed down by our Barranqueiro ancestors, inflicted by the Sobrinho dam spilling over – our intentions are to make roads and fix planks. To water the fruit trees in every yard. To assure ourselves that we can once again learn to swim against the current. To replace the cracked clay floor with water.

Tell us a bit about your journey to becoming an artist. What would say were the defining moments that set you on the path that you now follow?

Until I was 18, I grew up in Pirapora, a Barranqueiro city in northcentral Minas Gerais. My first references were the carranqueiro masters, my librarian mother and my fisherman and canoeist father. I was surrounded by books of poetry, rusty nails, baited hooks and lots of wood (in addition to our family’s backyards and the sound of a running river).

The most decisive moment in my journey so far was the death of my mother, in 2013. I spent a few years with blurry, dampened views, but it was only when I moved my body, suitcase and gourd to the big city that I came across the ”art scene” and understood the meanings of breaking up, walling up and keeping secret.

Tell us about the work you exhibited as part of The Square São Paulo. What is its significance?

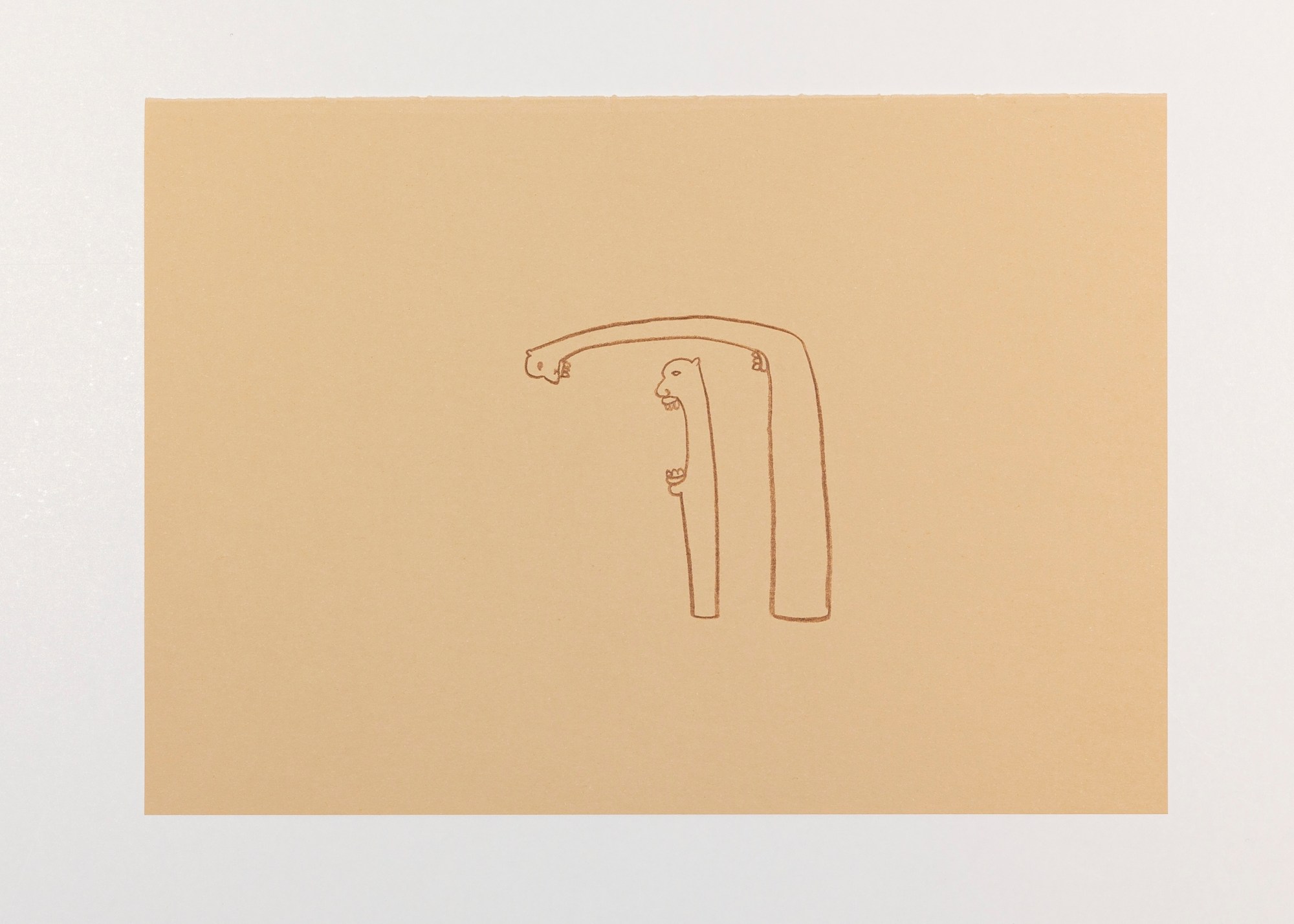

The drawings I showed at The Square are part of a series called Warning Cries, which I started working on in 2018, just before the crime committed by Vale [the Brazilian mining company] in Brumadinho, which caused the bridge we used to shake when people were crossing. The teeth that dug into my right hand compelled me to draw carrancas, and since then, I have been scratching out what my mouth cannot speak. This work is about the attempt to gather carrancas in a port that is infinite and protected by them; where each vessel has the power to glide over all types of waterways, even the densest and narrowest.

Gokula Stoffel

How would you introduce yourself and your practice?

I am a daughter of Hare Krishna parents, and until I was 10, I had a nomadic childhood in communities across Brazil. One of the experiences that impressed me the most was living in the Amazon rainforest and the dreams I had during that period. Now, those memories inform my visual vocabulary.

On the one hand, constantly moving made me always feel like a foreigner. On the other, it allowed me to witness many different worldviews from an early age and cherish their differences. That resonates nowadays with my artistic practice; not privileging one kind of visuality or media over another, and always leaving room for the unknown.

Tell us a bit about your journey to becoming an artist?

It took me a while to understand that art was a career possibility. In my teenage years, I wanted to study philosophy and ended up working as a model, photographer’s assistant and even salesperson in the fashion industry. That evolved into a desire to create clothing, and my way to start that was by taking drawing classes. After I did an immersive course that taught me drawing as a main vehicle to build ideas, and not just translate or express them.

Then, my artistic training evolved in a self-taught manner. I turned an empty room in my flat into a studio and started taking art classes and joining study groups guided by the interests that arose in the studio. In retrospect, I see that my crisis moments set me on the path I now follow. Initially, I was creating compositions with ready-made objects I collected, like paintings suspended in space. After a while, I felt those objects carried too many meanings and narratives, and I needed the work to become more my own. That’s when I started painting, initially using photographs I took as motifs. After my first solo show, I had a second major crisis, so I broke up with the idea of planning my compositions. That’s when I developed the process that I currently rely on most of the time. I start creating backgrounds and keep adding to this atmosphere until I see something on it.

How, if at all, does your work respond to Brazil’s current sociopolitical climate?

My response to my country’s current sociopolitical climate is subtle. In a more extreme condition, like the pandemic, for example, the pieces I was doing were dealing with the eminence of death in our lives and ideas of fear. Living in an extremely unequal country, I try to create works that do not rely on previous knowledge to be accessed, especially for those who feel no intimacy with the art world.

Tell us about the work that you exhibited as part of The Square São Paulo. What is its significance?

The work I’ve shown is a piece made of felt called “Windy Landscape”. It refers to an internal landscape divided by a horizon line that divides it into two fields, and the lower one is a distorted reflection from the upper. Playing with the idea of the double makes me think of amplified perceptions, the reality of things versus how we perceive them. Views from nature that convey emotional states are a recurring motif within my work.

Credits

Polaroid photography Pedro Pinho

Artwork photography courtesy of Bottega Veneta