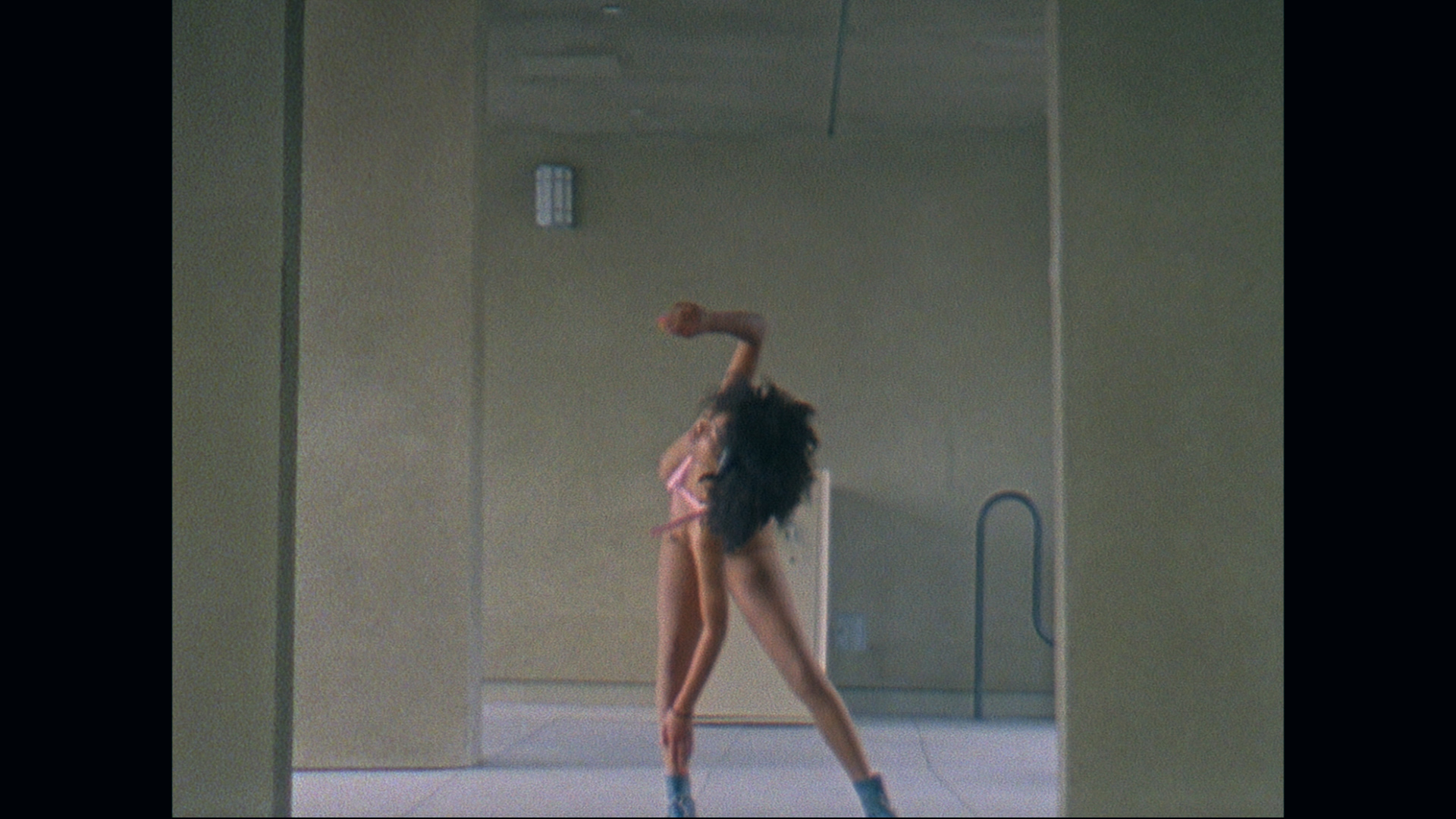

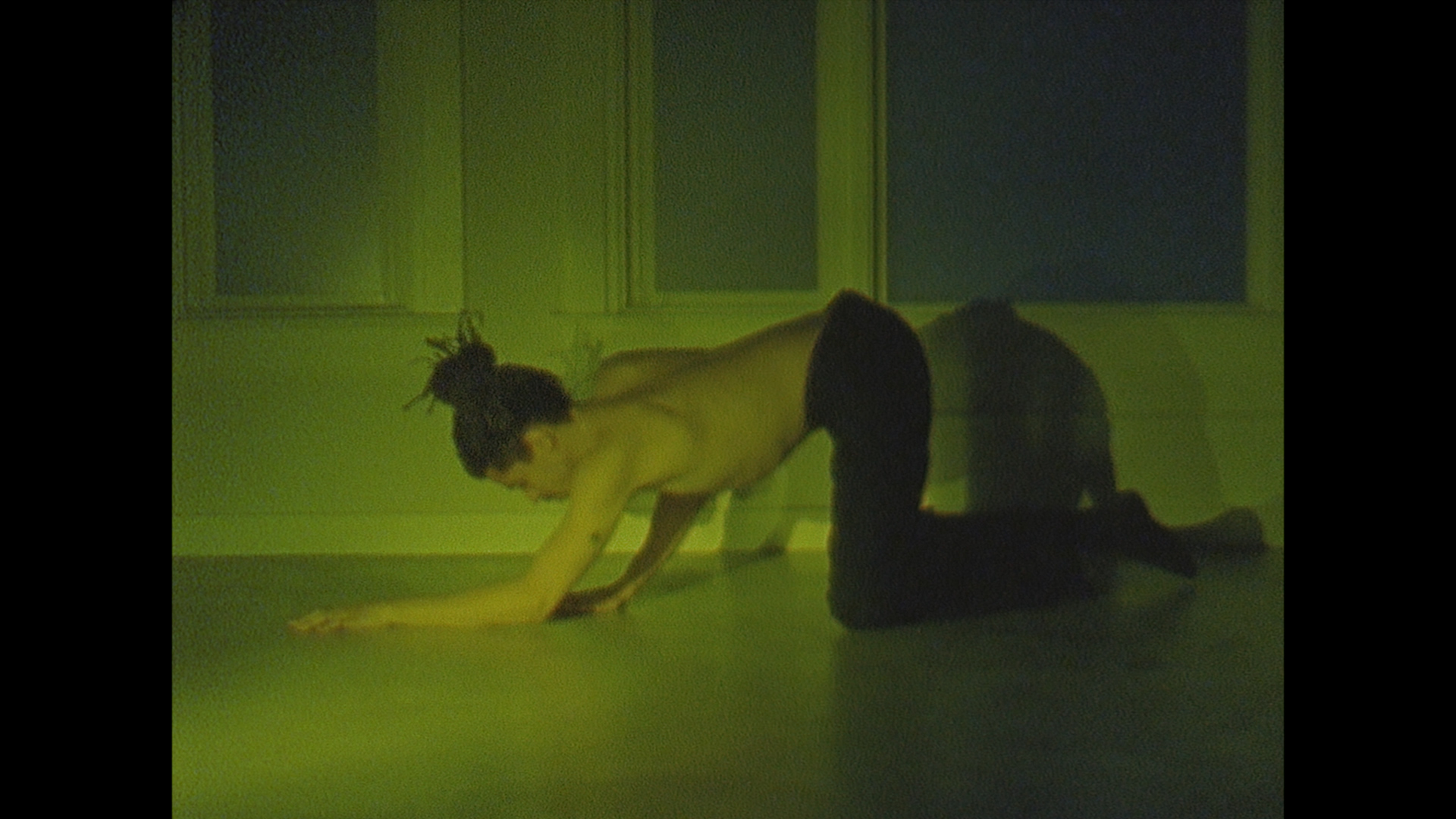

A woman meditates in a field of wildflowers, eyes closed, almost nude, her hair tousled. She slowly twists and turns her body, examining how her own parts move and find their form. She stretches each limb as if limitless, before letting out a silent, though still hair-raising scream. These are just a few of the opening shots from Cara Stricker’s new short film, Formless — Meditations in Music, which features Nadia Lee Cohen, Ajani Russell (of Skate Kitchen and Betty) and Sean Frank and premieres on i-D today. “I wanted to shoot people close to me, to look into how people felt around me in these times,” Stricker explains, “to capture that moment on film, listening to the experiences they were having internally, and communicate that.”

The short film deconstructs the idea of form and that which is beyond form, and focuses on silence, timelessness and existence beyond the self. It accompanies the release of Stricker’s ambient album of the same name. Formless — Meditations in Music was made over the last few weeks in her home in Los Angeles, and listening to it is meant to create a feeling of calmness. The collective work is an intimate look at what it means to free the mind, the body and the soul. It’s a soft and sensuous salve for our times — and it’s perhaps what we need most right now.

To celebrate the release of Formless — Meditations in Music, we caught up with Stricker to find out what it was like making a short film during quarantine and how we can all be a bit more ‘formless’.

How did the idea for Formless – Meditations in Music come about?

I’ve been thinking a lot about the universe, our friends, our community, our home and how all of this has brought us to a closer place of empathy and inner quiet.

I also wanted to make you feel good wherever you are, to peacefully tune out, and tune in. If you’re anything like me, moments of silence and meditations in sound has been a soundtrack to daily life. That’s where the concept begun, to be present in the sounds around us, letting both nature, and each other, breathe.

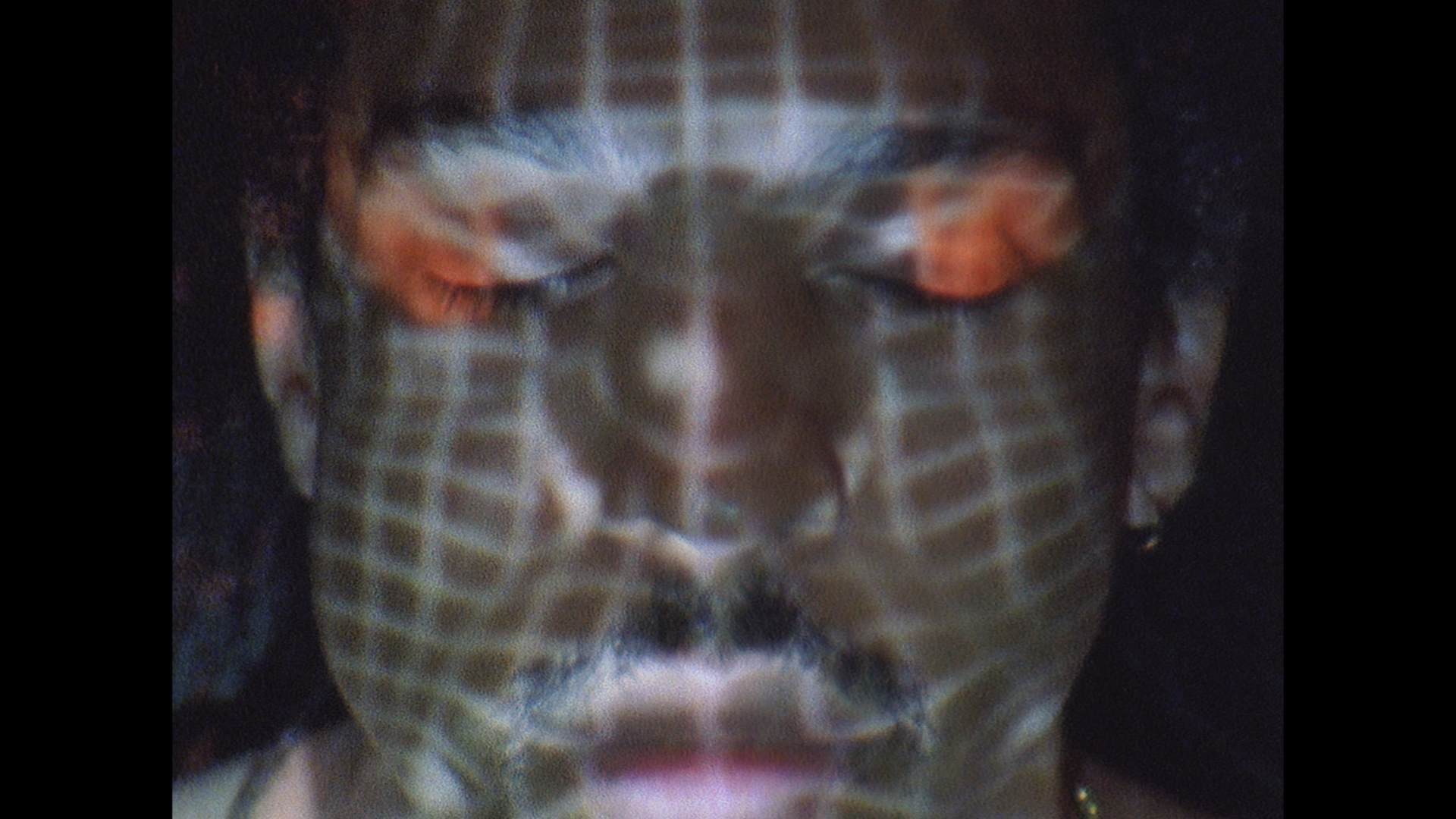

The film and music explore a deconstruction of the human form through movement or the lack thereof, the characters we play, the skin we are in and bound by, but by which we can also shape, and present like a sculpture. At home, looking at this interplay with these two worlds, that which we can see, and that which we can’t, is a fascinating and really important thing to re-evaluate right now, and take that experience into the future. To explore new ways of living, and being with yourself. It is a love letter to the earth.

What does ‘formless’ mean to you and how do you instill this sense of being in your work?

That you are neither in nor out yet you totally are, to be without becoming. To observe the senses that you are beyond, to observe the mind that you are beyond, to observe thought that you are beyond.

I try to capture that sense of being by reflecting it through different energetic progressions that we experience throughout the day in the visual textures, the storytelling, movement and score. Like life… chaotic at times, other times calm and reflective, and being able to observe that sensation of the spirit, through nature, framing and rhythm.

What made Nadia Lee Cohen, Ajani Russell and Sean Frank the perfect characters for this piece?

All friends, all artists in their own right, they were instinctually the first people I felt safe with exploring a very deconstructed version of filmmaking.

Nadia, in her artistry, channels such beautiful characters, so the idea of playing with the construct of the character, and stripping away at that to interplay with the raw human form, I find really inspiring to work with. Amongst the pandemic, it was fascinating to step in between the lines of identity and that which is beyond identity. Exploring our body, our skin, and what that looks like outside of the societal functioning and limitations of right now, and lean into the natural side of self.

Ajani I’ve shot a couple times for various projects. Her lucid, open nature and connection we share with poetry and inspiration coming from systemic dreams, makes a continuingly interesting character to keep creating with.

Sean Frank is a dear friend, and filmmaker. At this time he was one of the only people in my home, a person which I could safely explore carving out the visuals with. I wanted to shoot people close to me, to look into how people felt around me in these times, to capture that moment on film — listening to the experiences they were having internally and communicate that.

How did you work through the obstacles of making the film during this time?

The piece was born entirely in quarantine. Initially, Kodak and I were talking about a different film piece that we were going to shoot during this time. When quarantine was enforced, and every production shut down, we discussed perhaps exploring something more intimate. They are so supportive and dropped off a camera and film. I began to shoot, alone, without crews, simplified it all. I shot with 8mm film, loaded, pulled focus, operated and exposed. I leaned into the dogma of it, using the long zoom lens to be at least ten feet away from my subjects, using only what was in the space, projectors, flashlights, lasers in my home, and outside places that were open on the fringes of LA. I captured people who were around me, close to me, felt the same impact as me within the quarantine. We coloured virtually, from home, and edited from home.

The film development took weeks, as all our local businesses, like Spectra, who processed the film, are only operating every couple weeks if at all. It was a really incredible moment to see how the passion of filmmaking helped people during this time. The Kodak team would drive over to pick up the film I left outside for them. It felt really intimate, honest and freeing.

You were a dancer for many years and movement is a huge part of this film, and your body of work. How does your dance background influence your filming style?

So much of our communication, around 55%, is told through body language. Dance has been part of my life and language since it’s very beginning, so that has shaped how I tell stories. In this particular film, I wanted to explore the art of sculpture, in filmmaking. How we position the body in space. Movement or the lack thereof, defined the language of sculpture. I find the camera in itself dances, so the choice of how the camera moves with the subject, whether entirely still, or gliding with them, is all informed by dance I believe.

The short film accompanies the release of your ambient album. Can you tell us about it and how it all came together?

I was interested to combine frequencies and vibrations that lean into a calming, meditative, feeling in the body. It moves through progressions to drop deep into our inner rhythms and like life, it shifts between energies that we experience throughout the day.

I started making it without too much thought, everyday, a rhythmic meditation on music… Just letting each progression expand and contract, without judgement, and letting it be just what it was. The body of work surfaced after that. I found this experience very healing, and hope others can fall into that feeling. The music is there to close your eyes, to move, to make your own formless connection to your environment through sound, whatever that means, and looks like.

I was collaborating with a VFX animator in New York, Anton Woll Söder at the beginning of the pandemic, and we were exploring how nature, and our relationship to it, can be presented as a hopeful look toward spirituality, fusing nature within technology. This is where the animations are born from to accompany the music.

What have you been listening to these last couple months in lockdown?

Yusseff Kamaal, Spiritualized, Bob Dylan new and old, Inoyamaland, Gill Scott-heron, Toshio Matsuura Group, Nick Cave, Four Tet, a lot of classical spotify algorithms, Satoshi Ashikawa, Kraftwerk, Jamie xx’s “Idontknow”, Brian Eno, Pharoah Sanders, Yves Tumor, Dorothy Ashby…

What’s next for you?

Just finished the first draft of my first feature so hopefully that soon.… Let’s see. Then the next one I guess.

The film is supported by Kodak Motion Picture and Entertainment, and in support of shelter shorts challenge to raise money for World Central Kitchen’s COVID-19 food relief efforts. Donate here .