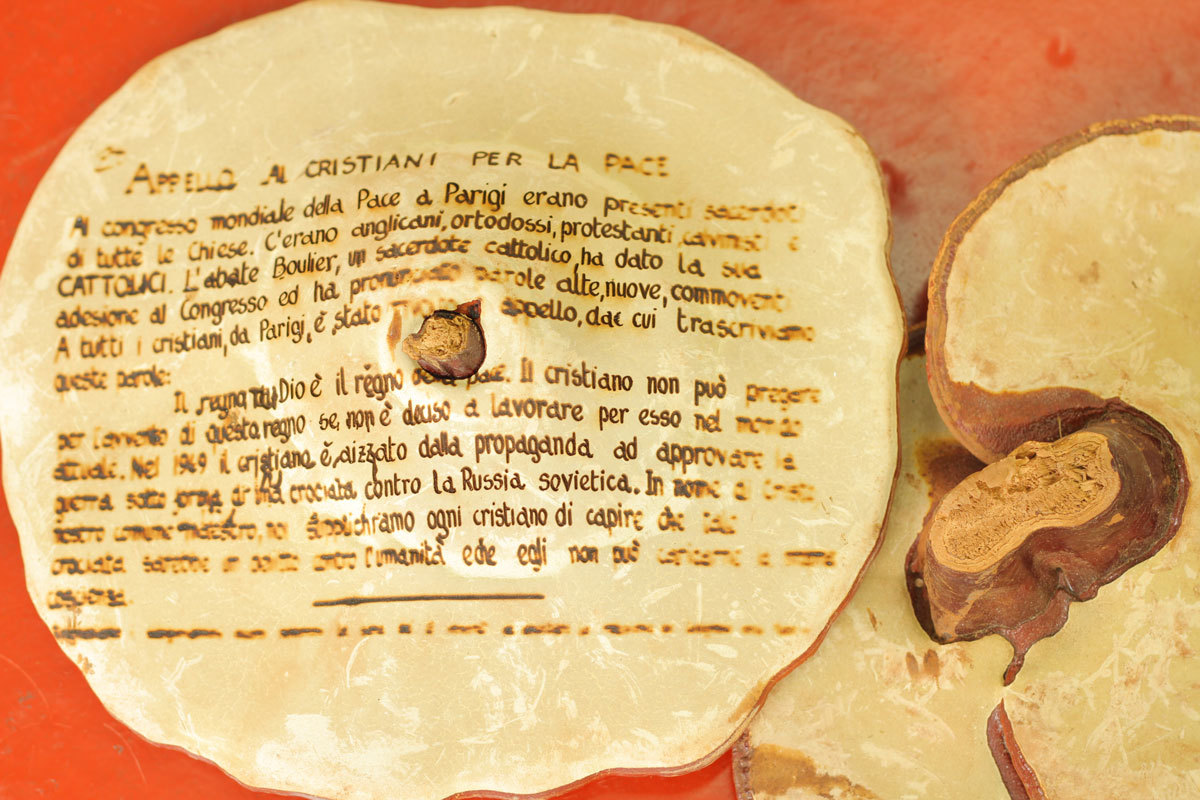

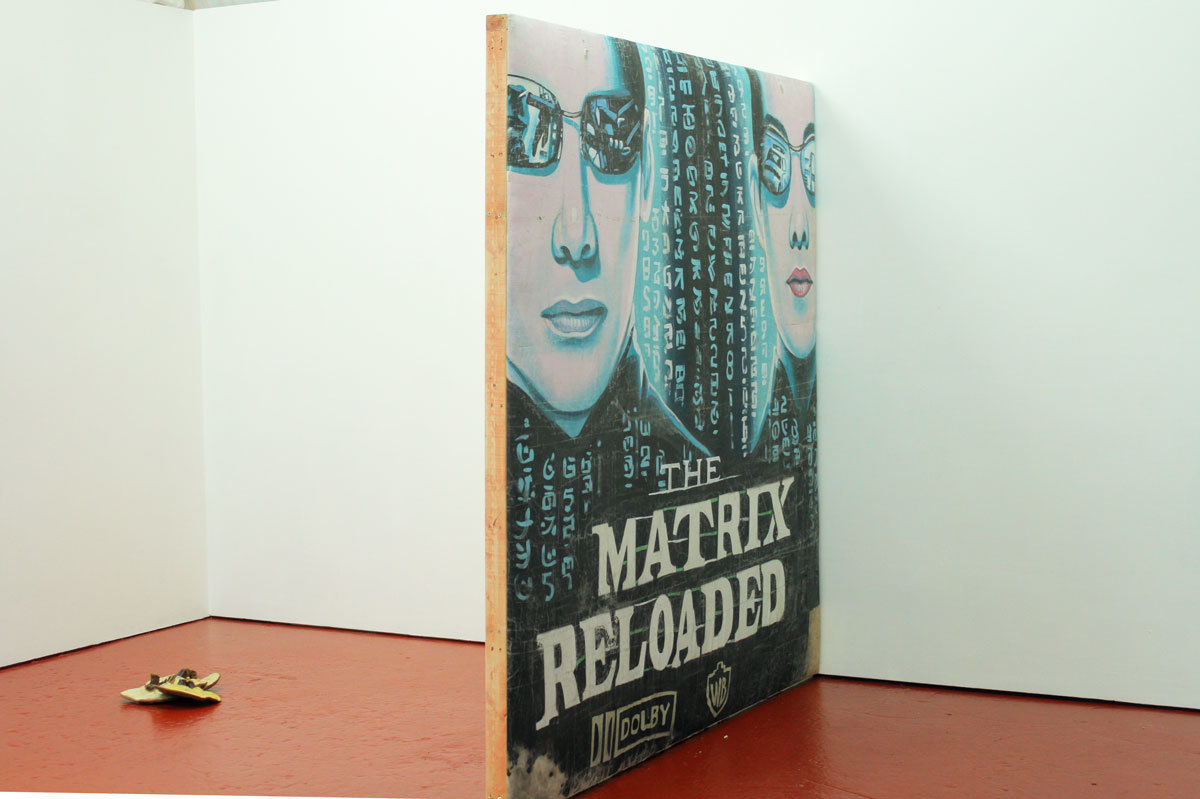

Dried Reishi mushrooms, laser etched with political provocations in the Italian dialect of Friulian, scatter the floor and walls. A hand painted Matrix Reloaded poster on a linen sheet is stretched across a hand built wooden frame, a wineglass resting on one of its rear crossbeams. Two shirts hang above head height, laser etched with burnt-looking text. The floor is painted deep, earthen red. An overhead slide projector delicately transposes an A4 reproduction of a poster onto a gallery wall, occasionally interrupted by the projection of a hand as you realise that it’s a live feed of a shelf containing the exhibition’s information and poster handouts.

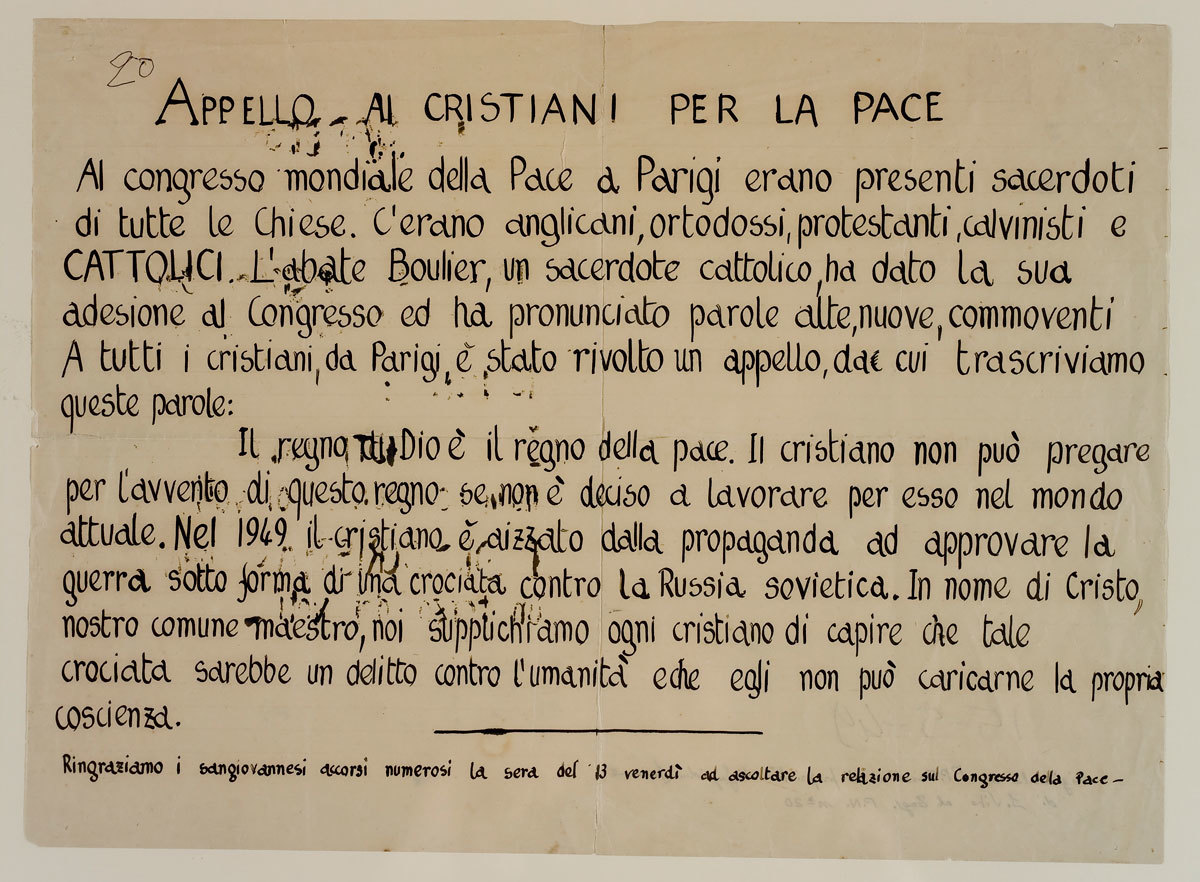

Carlos Reyes is an artist based in New York. Last week he opened the exhibition pindul’s rewards at London gallery Arcadia Missa. This put his sculptural practice in dialogue with Italian filmmaker, poet and political activist Pier Paolo Pasolini, who passed away in untimely fashion aged 53 in 1975. Organised by Italian architect and curator Alessandro Bava, the exhibition picks up on a series of pamphlets and posters produced by the young Pasolini in his hometown of Casarsa in the late 1940s. Made available by the Centro Studi Pier Paolo Pasolini, which is located in Casarsa and contains Pasolini’s archive, these digital files are re-situated within the material economy of today’s digitally permeated, globalised world.

A “Catholic Marxist” affiliated with the Italian Communist Party from 1947, Pasolini maintained a devout relationship to the rural working class, embodied in his use of Friulian and always present in the content of his work. Yet he was a cosmopolite comfortable in the big city and in international film circles. Resolute in political conviction, he was happy to embrace systematic contradictions as a starting point in radical thought – contradictions that are rife in any political or artistic work to this day.

The exhibition’s title translates the title of one of the featured posters (“Li sodisfassions dal pindul“). This tells the parable of two figures, one communist and the other a free market ideologue, arguing over who has the greater freedom: free market freedom to suffer from hunger, or the communist’s freedom to suffer the indignity of Alcide De Gasperi, the Italian Prime Minister of the time. If this is a debate still alive in austerity London in 2015, however unsavoury and opaque it’s become, it’s clear to Pasolini which the ennobling route out is.

What inspired you to work with the Pasolini archive?

Alessandro Bava: Pasolini’s work has been an obsession since I was a teen, and I found that outside of Italy he is known mostly for his films, so it was important to me to try and uncover lesser known facets of his work, especially his ventures into painting and drawing. The posters that are the base of the show are very unique artefacts because Pasolini made them in his early 20s in his more raw, early phase, so I see them as a synthesis of writing, political activism and art.

Is there a relationship between Casarsa in the late 40s and London today?

AB: Poor labor conditions… Bad housing… But the link is more Casarsa-NYC (where Carlos lives). I read an interview recently between Oriana Fallaci (the Italian journalist) and Pasolini, who after his first trip to New York states how obsessed with how people dress there he is, how “free” they seemed. For him the New York of the 70s was fundamentally anti-bourgeois, as much as the peasants in Casarsa.

Carlos Reyes: Casara has a complex history especially post-WWII given its proximity to Italy, Slovenia, Croatia and Austria. All these countries were divided along different political ideologies where pre-existing cultural ones already existed – Casarsa is in Italy yet shares the Friulian dialect with parts of Slovenia.

While London’s borders remain the same, its demographic makeup continually shifts. Its cultural borders are always in flux. There are countries within countries here, and competing political ideologies mixed with pre-existing cultural ones. Add to that the possibility of accessing information instantly and forming networks with communities of people globally and one gets the sense of a constant state of disintegration/ reintegration between the mindset of fractured marginal communities and psychologies, and the dominant consumerist hegemonic structure.

The works of Pasolini you are exhibiting are items of direct political antagonism, flyposted by Pasolini around his community. Is there a conflict produced when these things are brought off the streets and into a gallery space?

CR: The posters are 66 years old and the content refers to a specific time and locality, so perhaps by reinstalling them into gallery they are given a degree of universality. I hope placing them in Arcadia Missa provides a new context and thus new life, a new valence, rather than subsumes them.

But on a broader scale, the conflict only exists if you construct the relationship between politics/aesthetics as a binary. I’ve always wondered about this conflict between politicising aesthetics and aestheticising politics, and about how the realm of the sensual has been positioned as a counterpoint to the literary, absolute, rational, and political. I think one pulls the other and they sort of massage information out of each other. Sensuality is used as the scapegoat for manipulation of politics, instead of the actual people who are doing the manipulating in a very conscious way. This doesn’t acknowledge the possibility of permeability within our heads: I rarely walk around with a fixed position and am capable of assimilating information beyond binaries and beyond gestalt.

Another thing … why is a gallery considered a private aesthetic zone and the “public” a political zone?

AB: To me these belong to a gallery space AND to the street in equal measure, like a Rodchenko or a John Heartfield poster. With Carlos we tried to readdress the posters as works of an artist engaging his community. We saw them as political and poetical objects capable of triggering a reaction even within the gallery. I thought a lot about Pontus Hulten’s Poetry Must Be Made by All exhibition at Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1969 where images from the May ’68 demonstrations in Paris where literally taken off the streets and put in a museum. In that case the museum really turned into a space of conflict, so we wanted to deal with the political content of the works with more distance and in a more allusive way.

How do posters translate into sculptures?

AB: The idea was to deal with the posters in multiple ways: address their materiality as works of an artist while translating it both literally from Italian to English and as takeaway posters that are translated from a 90s American projector to a British power plug. We didn’t want to express respect for Pasolini, we wanted to express love!

CR: We spent quite a bit of time translating the works into English as well as looking at the physicality of the objects themselves. We looked at how they were edited, how they were hand printed, and considered the actual material they were printed on. In one instance we realised that the poster which had a decidedly Marxist view-point was hand printed on the back of a Christian Democratic poster. This was no doubt a conscious decision by Pasolini. The wording on the Christian Democratic poster bleeds through the front and graphically plays with the Pasolini text, which recounts a political situation that happened in Hungary. We found these design decisions interesting since they synthesised aesthetic decisions and calls for civic awareness. It was the basis for one of the material translations in the show, one of my own shirts with this “uncovered” poster laser etched on the fabric.

While having a conversation with a friend, he pointed out that I was speaking about the sculptures in very formal terms. For example, I had mentioned how I wanted to give some weight and volume to some of the posters. However speaking about them in formal terms is an acknowledgment of their physicality and doesn’t negate the conceptual effort behind the works or the task of translating them materially. Being given access to them as digital files on the Centro Studi Pier Paolo Pasolini’s website opened the doors for all types of reprinting given today’s “ubiquity” of printers, 3d printers, laser etchers, and digital distribution at our disposal.

Pasolini famously wrote in Friulian, a dialect of Italian originating in northeast Italy, where he was from. Do your sculptures have a relationship to dialect?

CR: “Dialect” is an interesting word because it presupposes that there is a universal standard of language and the deviations from that in tone, syntax, construction etc. as different and sometimes subordinate. However, two people speaking from the same regions, in the same language don’t hear “dialect”.

I suppose I give in to dialect in the sense that when I choose materials, I am not concerned with them being ahistorical vessels for universal truths. I like to think of the construction of the sculptures as more porous – as allowing for regional, time-specific readings of their component parts, and at them same time a rearrangement of those material expectations to uncover other possibilities in understanding what “truths” lay behind the perceptible world.