I first wrote about Charlotte Rampling nearly three years ago, because I kept running into her in different cities. She was usually alone, reading. I was usually alone at my computer. When it happened in Los Angeles and then, not long after, Paris, magical thinking took hold.

The subtext of that earlier essay was my ambivalence towards social media, how I wouldn’t show intimate moments with loved ones for fear of cheapening them. I think Rampling showed up IRL because I wasn’t spending enough time offline. She, nearly seventy, does not participate in social media nor, I imagine, would have if it were around years ago. Rampling’s abstention is common of her generation, and yet I kept seeing picture after picture of her in my feed. Somehow Instagram still managed to make her no longer feel like a discovery, like mine.

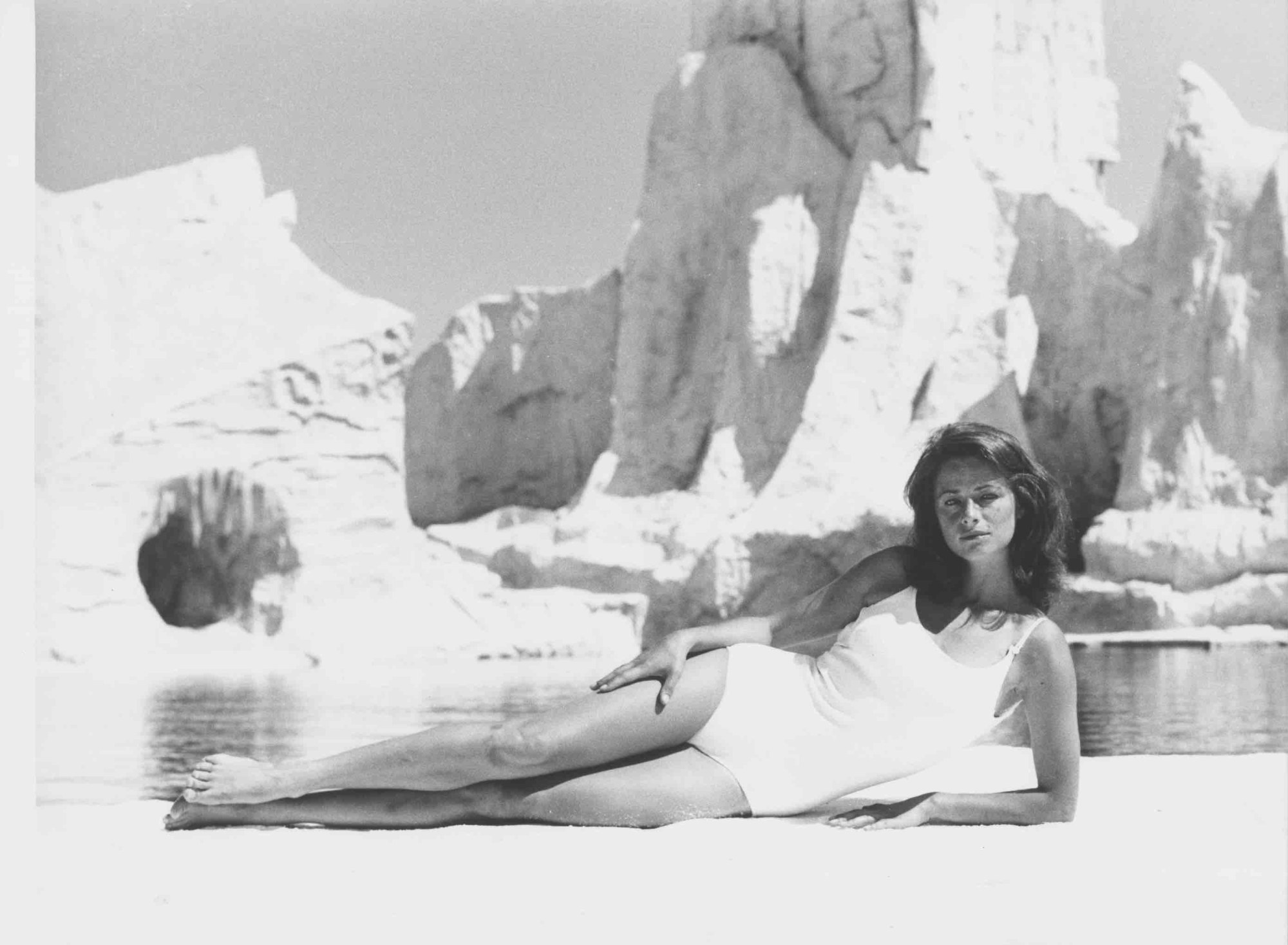

Since I was young, I’d watched Rampling’s films and collected tearsheets of her. I loved how she wore clothing with a kind of uncomplicated shrug, and how she looked even more comfortable when she took off these layers. It was less about a signature piece, more about an iconic stare and accompanying air of casual cool. I’ve never been very impressed by fancy clothes. I’m not even sure I can tell you my favorite Rampling outfit. I find her “style” equally memorable in film stills, when it’s clear the clothes are not her own.

The classic, impenetrable one from The Night Porter, Rampling as twisted lover Lucia, topless in black pants and suspenders, black elbow-length gloved hands over her breasts, hair pulled back, wearing an officer’s hat. Or there she is next to Woody Allen in Stardust Memories, in a crew neck sweater with short hair as the neurotic Dorrie. Then, her lesser known films, like James Salter’s Three. Here, she is Marty, the object of desire for two American boys, in denim top and jeans or subdued bikini between young Sam Waterston and Robie Porter. As Margaret Krusemark in Alan Parker’s Angel Heart, she is a little older, dressed in a navy blue blouse and calf-length skirt with white crochet detail.

All these looks and her famous photos sittings live online now, filed by hashtags, no longer hidden only in rare photo books. My obsession was marred when its empress multiplied, when she showed up en masse, a little army of proliferated images.

Rampling is also incongruous to social media in that she doesn’t – hasn’t – catalogued her own successes. She’s gone about her work, not looking for strangers’ validation. It found her. This is easier, of course, when there’s a stable of pictures taken by talented photographers, like Helmut Newton or Juergen Teller or image captures from art house films. More common to a younger class of artists are gossip items or embarrassing early work living online forever.

The problem with coming of age in the late 90s is that you made mistakes before you understood the power of technology’s new everlasting record. And now, all you have left is social media to course correct. But maybe that’s kind of great, because you once were unafraid and learning and evolving, not just projecting. Rampling also represents for me, a woman who continues to evolve as an artist, trying new things, as she ages gracefully.

As a writer, I find it interesting to examine how Rampling’s sensibility is transferred to the page. For years, I tried to find a copy of an authorized biography I’d only heard about. I asked various rare book dealers for help. No luck. It turned out, Rampling had pulled out of the project and not a single copy was to be found, nor trace of these interviews. Somehow this narrative collaboration must have not worked for her and so, she shut it down.

Just last month, she released a different project, Qui Je Suis, a kind of poetic, rambling “autobiography,” the summation of ten years working with editor and writer Christophe Bataille. It is an elegant wandering text, as far as possible from a “tell all.” I like this.

Rampling chose to recount memories in hazy, episodic stories, similar to her approach in the biopic documentary The Look. It becomes clear that she feels safer when a straightforward personal narrative isn’t required. And this explains why the false celebrity of social media or reality television will never create icons like her. That’s the problem with the internet. How to disappear and leave only the work.

We’ll be rolling out stories by our favorite writers on their personal style icons all week. Read them all here. Who’s yours?

Credits

Text Stephanie LaCava

Photography Stanley Bielecki for Getty Images