Francis Bacon is chic, fry-ups are chic, being happy is chic – according to the notoriously unhappy-about-everything Daily Mail – and Lorde’s Prada coat is chic. Bottega Veneta has resurrected chic, heroin isn’t chic anymore, but ketamine is, and being a disappointment to your family is chic. None of these words mean anything.

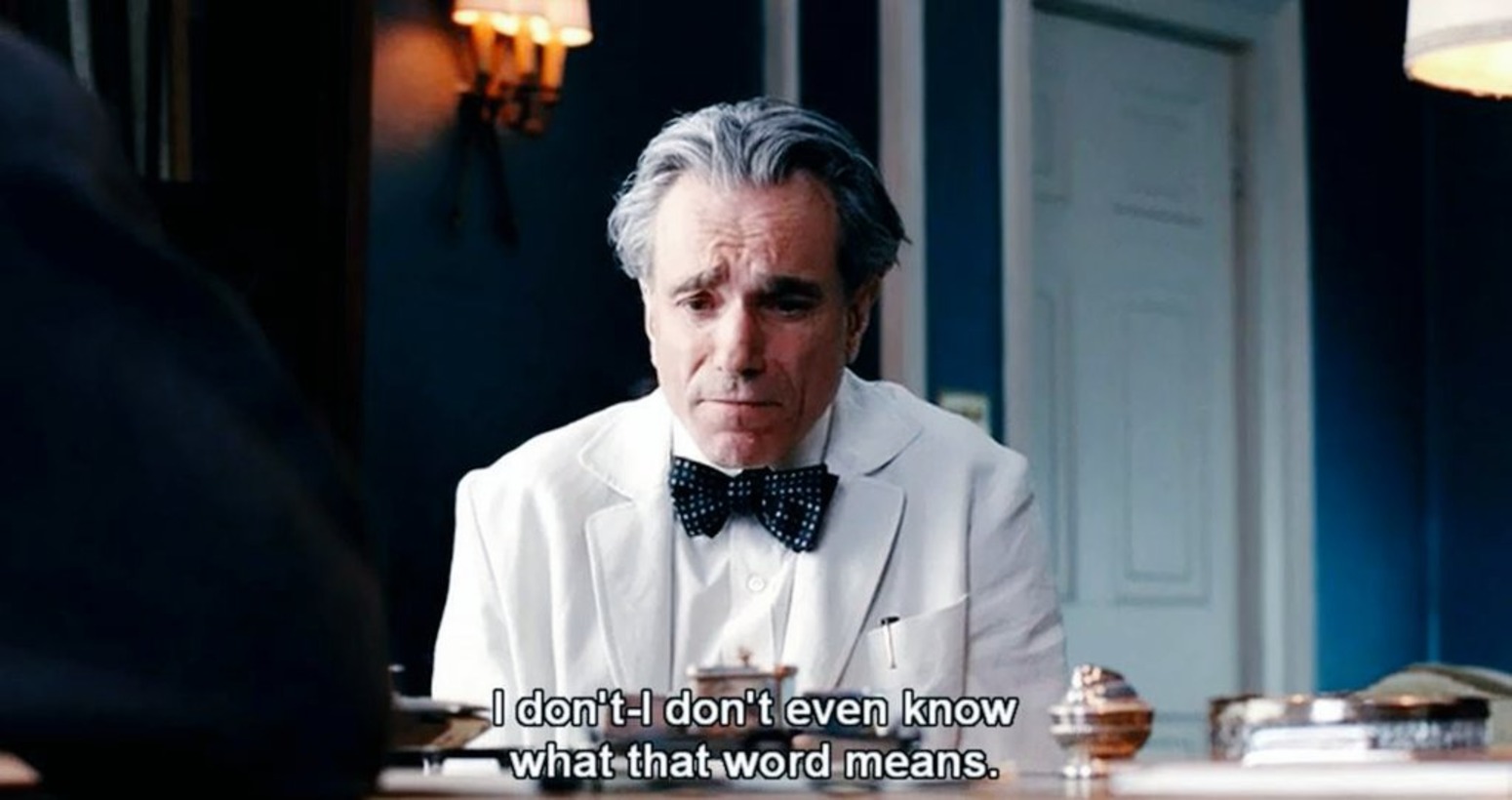

They don’t mean anything because we’re obsessed with describing things as chic, and as a result, sadly, nothing is chic anymore. We have killed chic. Chic is dead. Or dying at least. It was done probably before it approached three quarters of a billion views as a hashtag on TikTok. It was struggling after the release of 2017’s Phantom Thread, when Daniel Day-Lewis, as cantankerous British designer Reynolds Woodcock, railed “Chic? Oh, don’t you start using that filthy little word. Chic! Whoever invented that ought to be spanked in public. I don’t even know what that word means! What is that word? Fucking chic! They should be hung, drawn and quartered. Fucking chic”. (The Cut subsequently decided it was, as a word, as passé in fashion vocabulary as “glam” or “iconic”).

More recently, it neared its apex when Kate Moss played ‘chic or not chic’ to celebrate her new job at Diet Coke, declared modelling not chic, and it’s been downhill ever since. Chiming its death knell against the backdrop of Bottega Veneta’s defiant resurrection of chic, fashion critic Rachel Tashjian declared chic a lost art in our current age, an age where chic as a concept is near-impossible to attain (we can’t smoke inside anymore, everything is ridiculously expensive, minor celebrities are constantly doing notes app apologies for cheating on their not-even-famous wives, people use Twitter). “Chic is not merely an overused word—it’s a misused one,” she writes. “‘Chic’ has become the meaningless, maligned little term writers fling around as a catchall when they don’t feel like making up their mind about whether something is beautiful or interesting or just trendy.”

Chic has emerged as our favourite meaningless meme of a word at a time when what it means to be considered culturally relevant is more amorphous and uncertain than ever, a time when there’s never been more of a risk of going from beloved to reviled at breakneck speed. Fast fashion and TikTok mean trend cycles move faster than ever, which is why, every week, we’re being presented with something ridiculous with the suffix core – blokecore, barbiecore, goblincore, cottagecore – as though this makes it in any way a real thing. If ‘core’ has replaced ‘trend’, has replaced ‘fashion’, then ‘chic’ has simply become a byword for ‘style’. Cores may come and go, but chic is forever, by this logic. But chicness has never been a synonym for style. There’s something less tangible to it than that. And because it’s always been something intangible, like charisma or the presence of God, it can mean literally anything.

“I think it isn’t quite as ubiquitous yet as random, or mood, or slay,” says Tom Rasmussen, a writer and columnist and presenter of cult fave Instagram series ‘chic or not chic’. “It’s a little more refined, and multilayered. But the way we have started to use it, in the UK at least, is actually a translation of the typical French idea of chic, which is really I think is different, specific things.

“There’s the typical usage, ‘oh my god, Marie-Amélie Sauvé is so chic’. And she is, in the typical sense. Then there’s the use of chic to reclaim something tragic or camp: crocs, or undercooked chicken or falling down at baggage reclaim. There’s something chic in the failure of it all, there’s something chic in knowing and reclaiming.”

And so we’ve adopted it in a memetic way to be used merely as a synonym for ‘cool’ – you could comment ‘chic’ under someone’s Instagram and they’d know you meant ‘you look cool!’ without the indignity of actually telling them so – and ‘cool’ historically, means nothing, or it takes itself far too seriously to mean anything even adjacent to chic. Or, as Tom says, we’ve adopted it in an ironic way as a synonym for camp, to celebrate the fun, vulgar things we like which would otherwise have been considered bad taste. Or we’ve adopted it as a synonym for aspirational, a way to perform something about ourselves, rather than being something we inherently possess. An individuality or constancy that isn’t beholden to trend-cycles and is still somehow timeless, something that makes you stand out without being odd. But all of that’s a misinterpretation of what chic actually is, if it was ever something that could be defined in the first place.

“Chic is not aspirational. Chic is the most impossible thing to define,” wrote Luca Turin, the legendary biophysicist and perfumery writer (a chic job combo). “Chic is all about humour. Which means chic is about intelligence. And there has to be oddness – most luxury is conformist, and chic cannot be. Chic must be polite and not incommode others, but within that it can be as weird as it wants.”

Chic has never meant anything then, you could argue. What’s the difference today? What makes it such a particularly meaningless term now? The answer is, as always, the internet. The concept of chic was always something difficult to grasp and define, but Luca Turin and Karl Lagerfeld and Francis Bacon and Coco Chanel, none of them were forced to define it in the age of Twitter and TikTok – where one person can say something is chic or unchic and all of us, en-masse, can instantly decide if it’s funny and if we want to make it true. And then brands can capitalise on it, mass-producing whatever concept or idea or trend we have decided is chic, somehow never fast enough to stop it being over by the time it reaches shops. Words and ideas are disseminated much faster, and become meaningless quicker than ever. We have access to more information than ever before, and we have access to it all at once; a state of affairs that could be chic and intellectually exciting and interesting but is, in practice, just kind of annoying.

Perhaps because we’re living in the era where chic feels both overused as a word and dead as a concept, it feels easier to define things as the antithesis to chic rather than being chic itself. “As with anything, chic is often defined today by what is not chic,” Tom says. “Like, champagne coupes are overused and unchic, so champagne flutes are now chic. Again it’s a reclamation.”

It’s true that it’s more fun, more easy, and more internet-neg-friendly, to disparage things as unchic rather than chic. Being gender-critical, for instance, that is unchic. Working five days a week is unchic. Getting Covid in 2022 is unchic. God Save the King is unchic. Asking “can I pay contactless?” is unchic. Elf Bars are unchic. Lime Bikes are unchic. Being on the pill is unchic. Instagram pastel infographics are unchic. Describing an article as an ‘essay’ is unchic. CBT is unchic. Members clubs are unchic. Small plates are unchic. Having a newsletter is unchic. Natural wine is unchic. Getting married is unchic. Tarot is unchic. Trying to buy a house is unchic.

But again: none of this means anything. It’s all just a way to perform culture, cultural knowledge, and cultural capital. A way to prove you’re a serious, or interesting, or cultured person, without actually being serious or dour about culture or being interesting (which is, of course, unchic). “In the end: it’s actually just a lot of fun,” Tom says, “and it’s a way to try to understand your own taste.”

But beware: like ‘random’ in the halcyon, nascent-internet days of the early-2000s and ‘slay’ in 2021, bleeding into 2022, ‘chic’ is fast-becoming nothing more than our word-du-jour, something that we can use to death, use until we’re sick of it. Eventually it’ll become so ubiquitous – arguably it is already – that its use becomes in itself, fundamentally not-chic. Perhaps it’ll become so definitive for our current moment that it’ll become the next Dictionary Word of the Year, immortalised next to entries like “emoji tears of joy” (2015, not chic) and “vaping” (2014, not chic), and “youthquake” (2017, take a wild guess). Our over-investment in the cult of chic will inevitably become a moment in time as much as millennial pink and the Harlem Shake. How deeply, intolerably unchic.