The story of Dior starts, technically, in the second week of December 1946. Although really, or at least in the public imagination, it begins on the 12th of February 1947. Christian Dior had formed his company that December — after a period running an art gallery and then working for fellow French designers Robert Piguet and Lucien Lelong before he was called up to the military — with the backing of businessman Marcel Boussac.

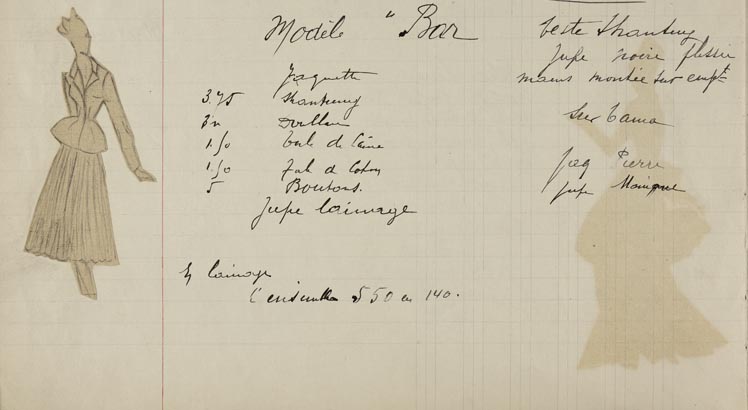

But it is the latter date — the occasion of his first show — that has gone down in history. It was the birth of “The New Look” — the moment fashion re-emerged after wartime privation. The most vital and enduring symbol of this renaissance remains the Bar Suit. It is deceptively simple; a white satin jacket with soft shoulders and a dramatically nipped-in waist, a flowering expanse of black skirt radiating outward from it. It’s a silhouette that seems to embody and define elegance, sensuality, modernity, purity, Paris as a city, youth and newness. Maybe even fashion itself? It still has that capacity to summon these feelings 73 years on.

And on the occasion of the Bar’s 73rd birthday, the label are launching a new permanent collection — named 30 Montaigne, the address of Christian Dior’s first atelier, and the location of that very first show — of which the relaunched Bar is the star and centrepiece.

The Dior Archive is located just across the street, and is run by Soizic Pfaff, who has worked for the maison for 46 years now. In the long history of Dior the archive is a relatively new development though, and only really began to be organised in earnest after Bernard Arnault bought the company for a single franc in 1984, the company on the verge of bankruptcy. Arnault staged the first retrospective of the house in 1987, to celebrate its fortieth anniversary, and soon realised just how much of the history of the house was missing.

There was a lot of documentation but “almost no finished garments,” Soizic explains, pulling books, files, folders and magazines down from shelves to illustrate the history of the house and the Bar Suit. Bernard Arnault quickly realised the importance of maintaining the history of the house, and they began to track down the most interesting and exciting haute couture pieces from the history of Dior. The first donation to the fledgling archive came from the collection of Princess Grace of Monaco — hardly a bad place to start. “That was the beginning of everything,” she says, “and then we started to begin buying back pieces, and it’s still a process that goes on”. Soizic moves swiftly around the library of the archive, the documentation is fascinating, tracing Dior’s beginnings and expansions, his creative and commercial genius, his ability to play the press.

But the creative cornerstone of this history is the Bar Suit. It was an immediate success. Shocking, exciting, tantalising and new. It was exaggeratedly corporeal and also alluringly impressionistic in the way it emphasised the body. “Mr Dior didn’t like the way women dressed during the war,” Soizic explains of the motivation behind it. “He really wanted to completely change everything. He wanted more femininity, more elegance, more happiness, he wanted to show the curves of the body.

“Growing up, before he became a designer, he wanted to be an architect,” she continues. “And the Bar Suit is the purest expression of his love of architecture.” One of the many things the archive shows is how quickly the company grew off the success of that first collection. Christian Dior did not set out to create a global fashion empire. “At the beginning he didn’t want to create this very big house, he just wanted to work with a few clients from a few countries, women who were very rich and beautiful and elegant. Then straight away, he realised how successful it could be and began to expand.”

The Bar Suit was the revolution. Dior doubled in size as a company every year between ’47 and ’57, when he died. He was generations ahead of his time in the way he utilised the press to help create scandal and excitement and interest around what he was creating. He quickly expanded to the USA, London, South America (the first actual Dior boutique was not in Paris, but Venezuela, a store operated alongside Cartier) and Japan.

He translated his first book — Je Suis Couturier — into six languages and serialised it in magazines. Criticism on the front page of a newspaper, he once said, is better than being praised on the last. If that initial vision of The Bar Suit was the revolution, over those 10 years as a designer under his own name, he continued to evolve it. “The Bar Suit is really only that original 1947 design,” Soizic says, “but it became so popular that Mr Dior continued to reference it. It appears in 1950, ’55, ’57, the last collection…”

After his death, and as a succession of creative directors followed in his footsteps, the Bar Suit only seemed to grow in importance for Dior, its impact becoming a definite marker of a change in fashion, heralding too, a new kind of fashion industry. Marc Bohan, Gianfranco Ferré and John Galliano all looked to the Bar at times during their tenures at Dior, but it is the spirit of it that seems to reverberate most rather than a strict interpretation — after that initial shock it retains its feeling of femininity and elegance. And it is, despite its very specific shape, quite adaptable.

Soizic pulls down book after book, tracing echoes of it here and there throughout the decades. A shock of white and black, and it becomes cuter or more rarified, easier or stricter, exaggerated or subtly alluded to. In Gianfranco Ferré’s SS91 haute couture collection, the sleeves billow out loosely, the black skirt replaced by the cascade of white, more cute dress than power suit. Galliano later resculpts it, drags it back towards grandness and glamour and femininity.

But maybe most of its modern focus can be found in the recent work of Maria Grazia Chiuri and Raf Simons. Raf Simons sought to minimalise and modernise it, making it sleeker and sexier, pushing it as the cornerstone of his new, romantic vision of Dior. Maria Grazia has continued to rework it, finding new feminist angles within it; softening its lines into something quieter, paired with a T-shirt maybe, or reworking that white-black strictness of colours into shades of grey. Adapting it, too, collaborating with Grace Wales Bonner for the house’s Cruise 2020 show in Morocco, seeing it not just as historic relic but as something continually new.

The latest iteration finds it now embedded at the heart of the house’s permanent collection, relaunched today in a similar fashion to the Saddle Bag, on the backs of influencers across the globe. Spreading via a new virality — one that Christian Dior, that master manipulator of press reaction, would probably appreciate, understand and be fascinated by — it again proves this jacket’s status among the most versatile, enduring creations in the history of fashion design.

When asked what Soizic thinks has caused it to not just endure but thrive for 70 years, she says it is “elegance”, quite simply. Which it certainly has, but it’s an “elegance that can transform you” — it seems to carry with it something original and powerful, a pure distillation of beauty. There are some garments, that when you wear them, seem to change how you carry yourself through the world. The Bar Suit might just be the most powerful of them all.