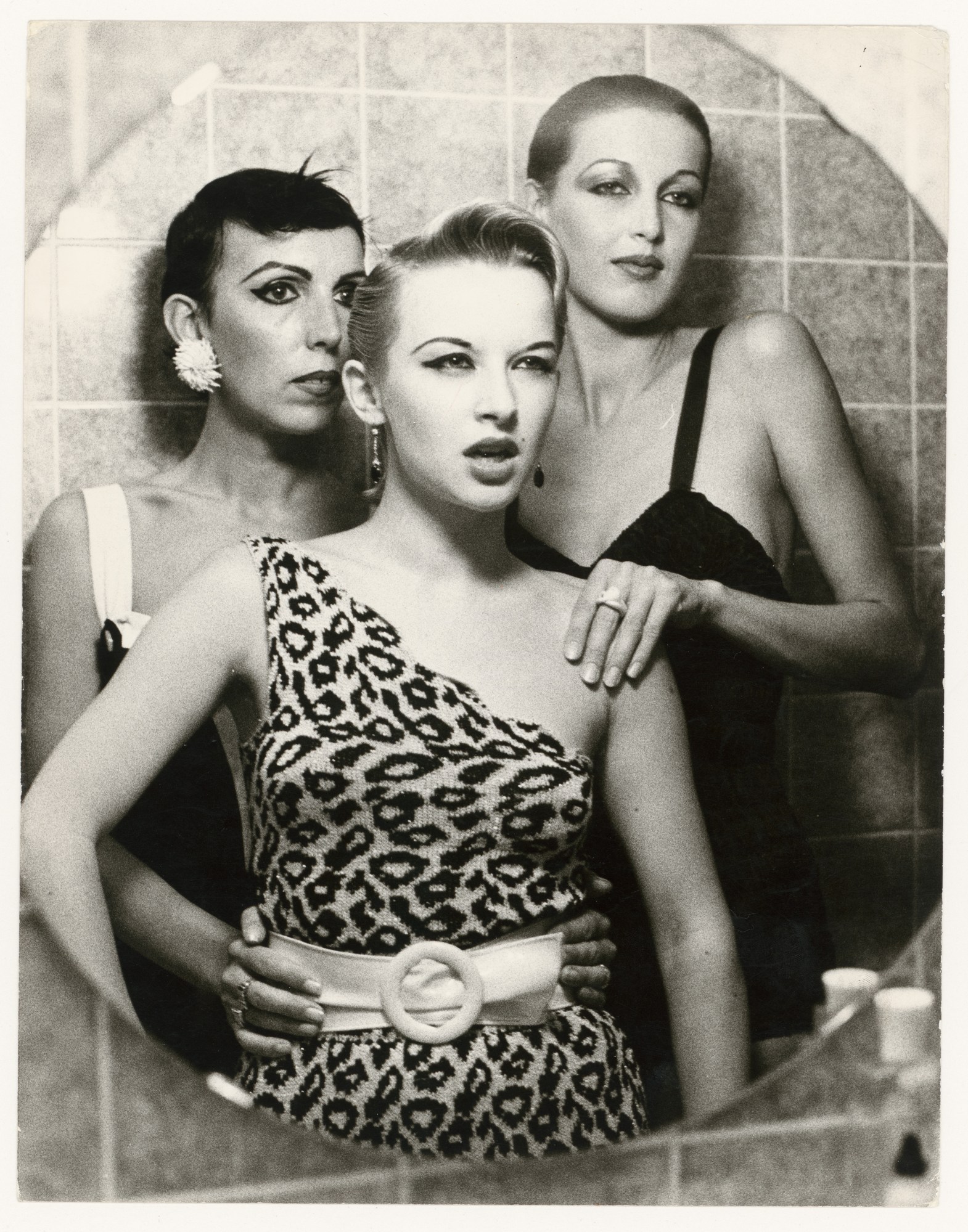

In the early 1970s, German fashion designer Claudia Skoda joined an experimental Berlin collective. Based in an abandoned Kreuzberg factory, their studio space, the ‘fabrikneu’, loosely resembled that of Andy Warhol, with a revolving door of cool upstart weirdos: a model who posed for Helmut Newton, an artist who would go on to gain international recognition and a percussionist for the band Tangerine Dream and Iggy Pop, to name a few. Claudia’s speciality, knitwear, was its own kind of playful aesthetic reinvention.

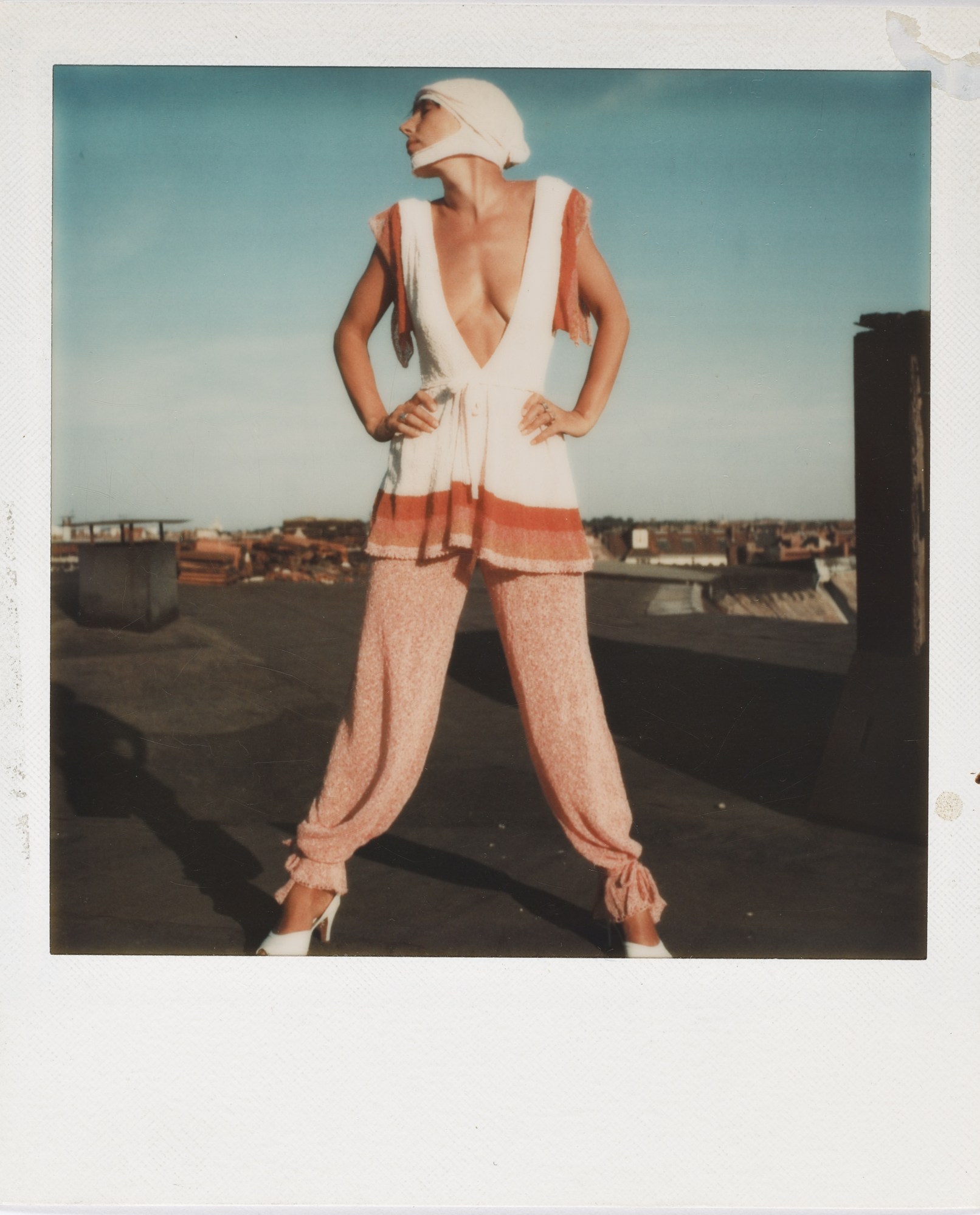

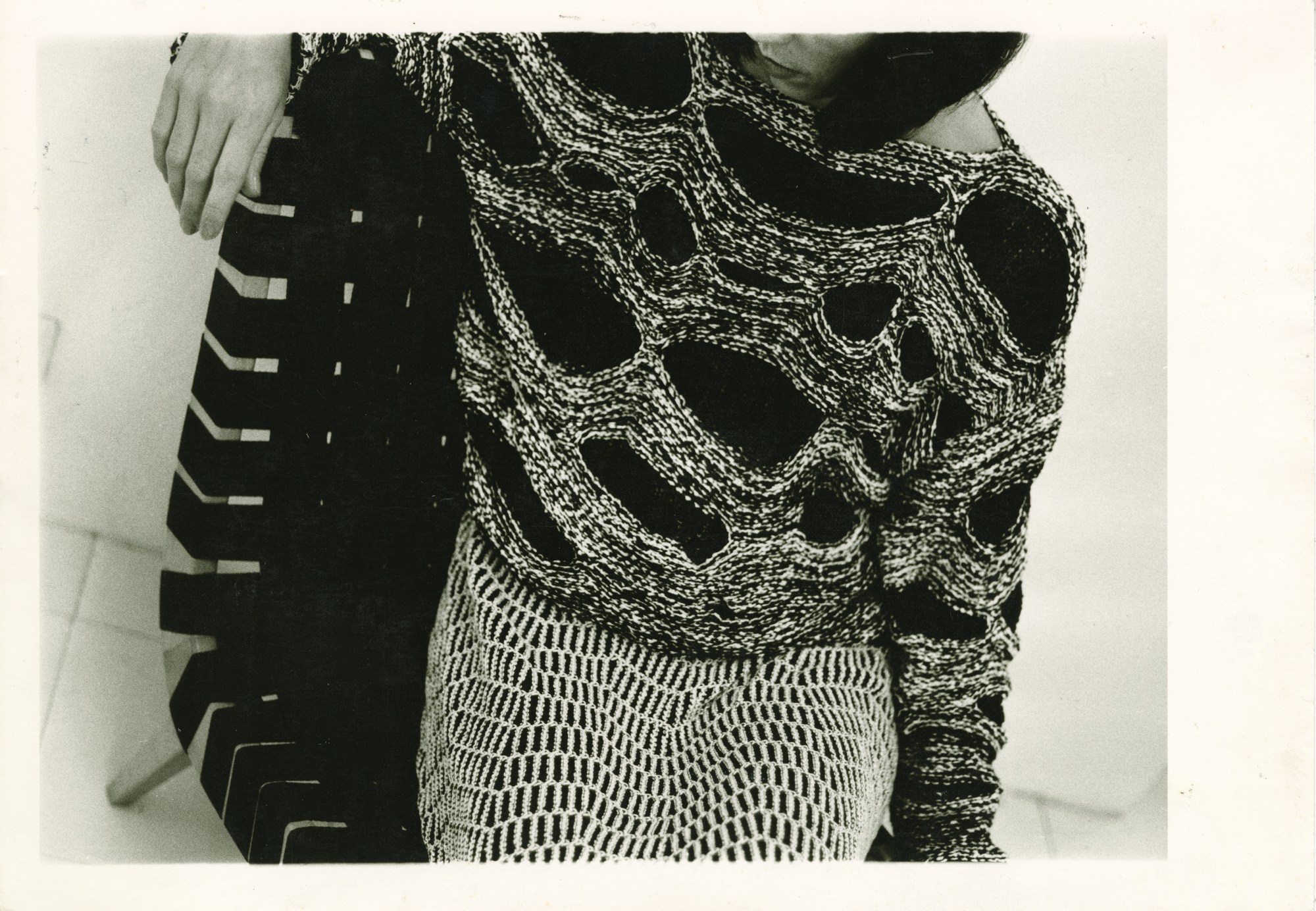

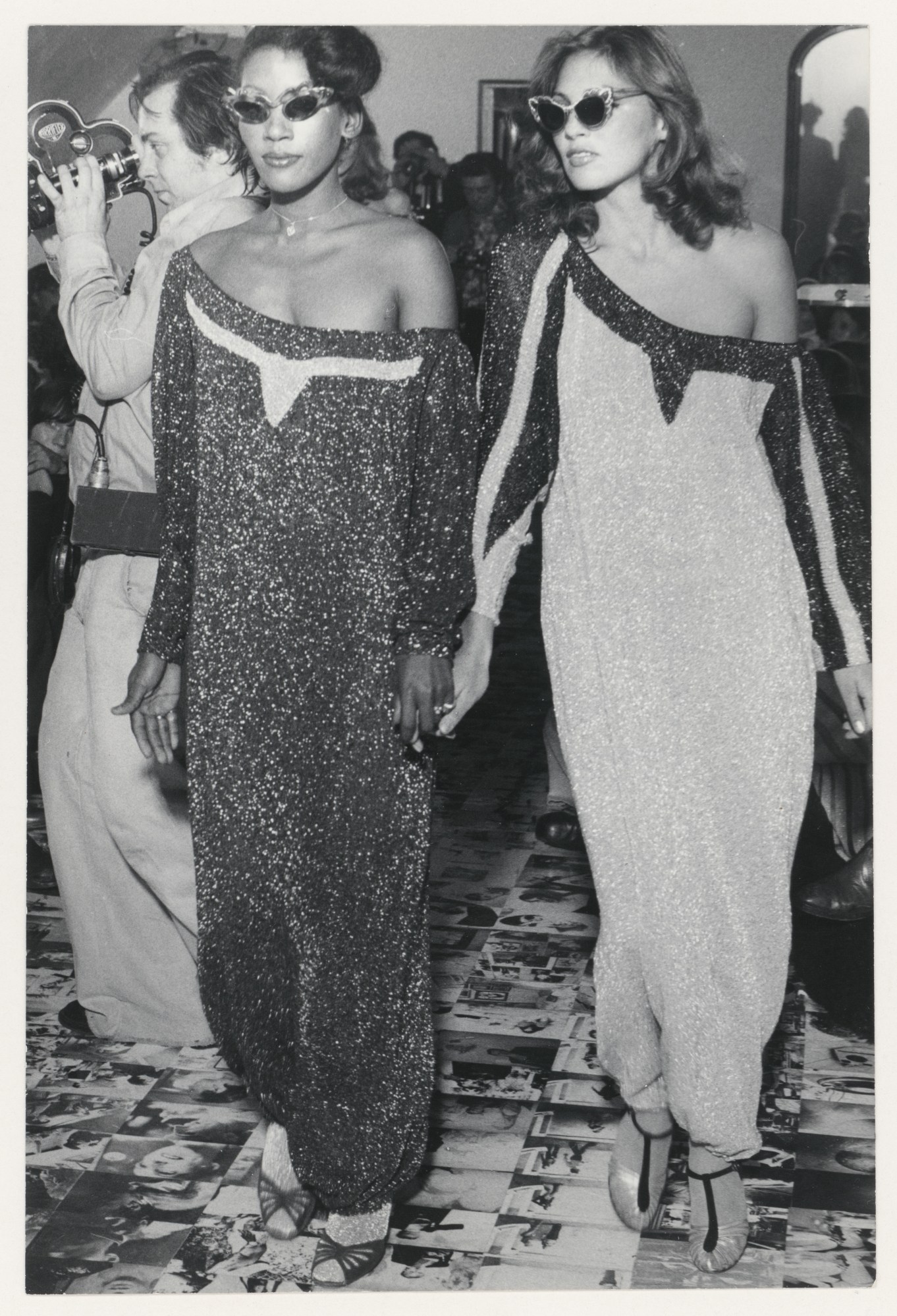

Entirely self-taught, Claudia began playing with a flatbed knitting machine in the late 1960s, when she couldn’t find the kinds of clothes she wanted to wear anywhere else. Though knitting isn’t necessarily a medium one associates with counter-culture, Claudia designed fluidly and liberally, creating garments that became synonymous with the era and would earn her a reputation as the “queen of texture” (PAPER, 1985). Dressed to Thrill, a new exhibition at the Kunstbibliothek in Berlin, takes a look at this striking sartorial output throughout the 70s and 80s — lots of graphic bodycon pieces with insouciant slouch — as well as the fertile creative scene of West Berlin.

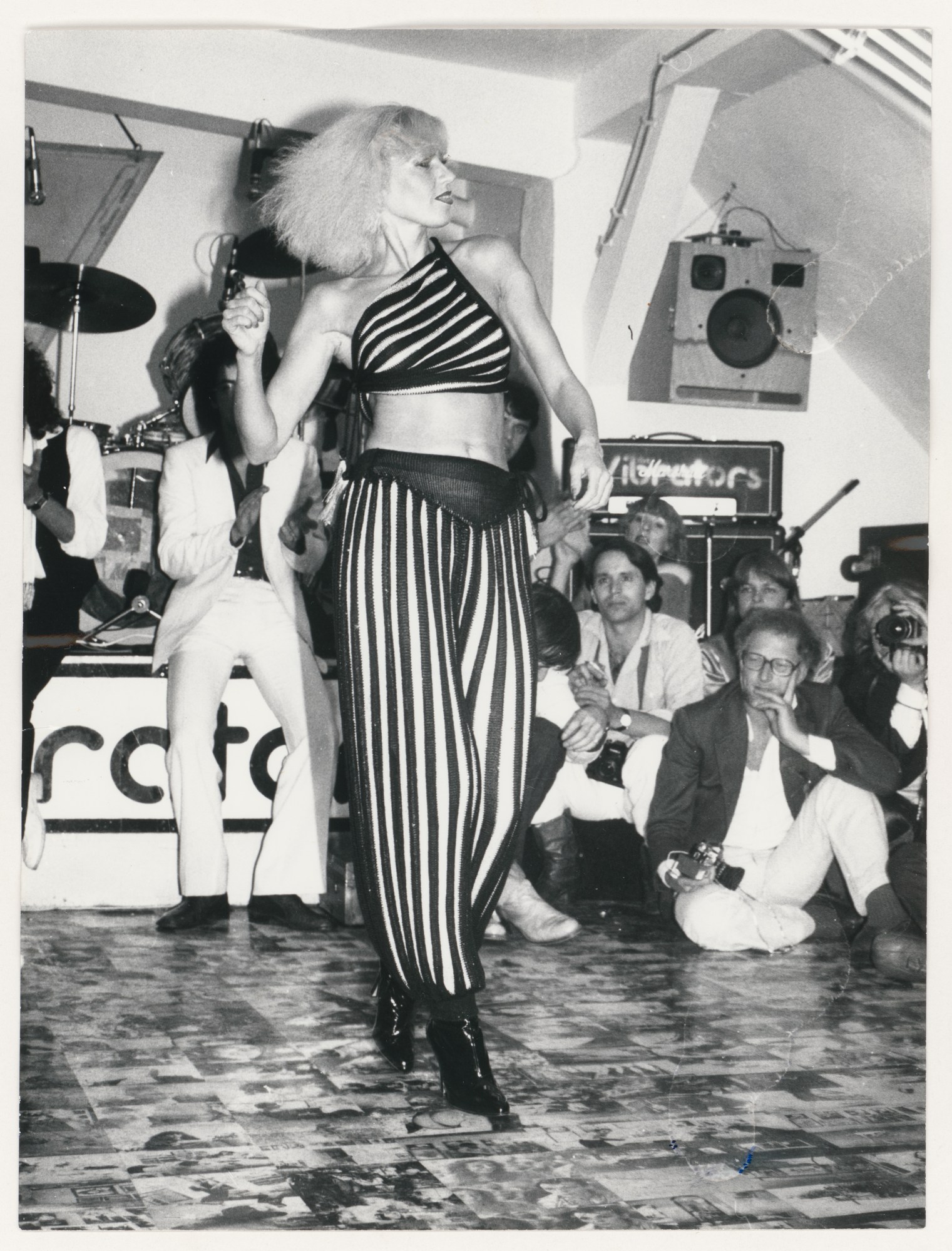

“Knitting is often associated in a clichéd way with housewives and eco hippies,” the show’s co-curator Marie Arleth Skov points out in the exhibition catalogue, “[but it can] make statements about queerness, or push gender stereotypes to the point of absurdity”. Pointing to artists like Rosemarie Trockel, Louise Bourgeois, Tracey Emin, and Mike Kelley, Marie asserts that, in the right hands, knitting can refute “certain notions of domestic/female existence”. Elsewhere in her designs, Claudia made wide pleat-front trousers and broad-lapelled jackets for men, and skintight womenswear out of latex and Lurex. She staged elaborate and disruptive fashion shows to present these progressive garments; the kind that would see models hatching out of giant eggs, for example.

With the exhibition opening this week, we called Claudia to discuss the pros and cons of Germany’s former isolation, the allure of New York City and the art of translating a mood into music.

What state were your archives in? Did you have a sense of the story you wanted to tell for the exhibition, or did you discover it along the way?

Two years ago, the curator and I went through everything. I wanted to do a [full] retrospective but once we started, we realised I have too much material — so we stuck to the 70s and 80s. In the beginning, I worked with different materials and style; it wasn’t until the mid-80s that I developed the knits I’m still working with today.

How was your brand shaped by the fabrikneu? It sounds incredibly collaborative.

I tried to include all the creative contact and energy [from the studio] in my presentations, fashion shows and photos. We were kind of the centre of a scene in Berlin; mostly artists who lived in this abandoned factory with us. There was a lot of going in and coming out, and New York people would stop by for music sessions. I did short movies, and I made a catalogue about my creations. In Berlin, there weren’t many brands: only a few designers, mostly haute couture. It was an open world: we did our shows in our factory, and clients came from all over Europe. In the beginning, we made a lot of stuff; then we picked things. It was not very economical! We went to fashion fairs — in Dusseldorf, Milan, Paris — and took pre-orders later.

Several pop culture icons sported your clothes: David Bowie wore your trousers in the 1980 music video “Ashes to Ashes,” and clients at your New York boutique included Cher and Donna Summer. How does celebrity register for you as a designer?

We lived on a kind of island — Berlin was closed off, and we had a hard time being connected. That’s why I decided to open my store in New York [on Thompson Street in SoHo]. David Bowie was a friend of ours, and he said: ‘you should go to New York or London or Paris.’ That was in 1981; in 1982, we opened a store. Vivienne Westwood’s store was across the street from mine, so I could always see what she was doing. I liked the way she was presenting her own style and the way she was working in the industry. I travelled between Berlin and New York all the time. In New York, I met people and realised what my standing was — I couldn’t figure that out in Berlin!

What was your standing?

Well, [seeing] how other designers worked, it was a totally different way of doing business in America. It also totally changed my style, in a way. It became a more international influence: American showbiz, but also Japanese designers [Comme des Garçons opened a store in the neighbourhood]. New York was about high sophistication — but it was also about streetwear. And this made me think not just about evening dresses or party dresses, but wearable clothes for the day that are themselves outstanding. It was a new ‘measurement’: that an item of clothing should be special, international, wearable. I transferred those influences to Berlin.

How did you get into fashion design in the first place? You worked in publishing initially, but your father was a tailor, and you grew up with a relationship to textiles.

My father was a “real” tailor — like Savile Row style. As a child, I would sit in his workshop and think how hard it was to work on a suit or coat jacket. I couldn’t imagine doing that. In the mid-60s, young people came to Berlin, but there wasn’t really anything for them to buy. I went to London, or Paris, or Amsterdam for clothes. I went to second-hand stores, and my inspiration was fashion from the 20s. I thought, ‘it’s hard to find good clothes in Berlin’ — so I started making some, using a knitting machine. I liked knit as a medium because I could play with the colours and shapes and transparencies. It was how I found my way forward. And the vintage inspiration [confirmed] my aesthetic — nothing I made looked like it had come from a department store.

How did your relationship to music evolve? You did some experimental electronic stuff yourself, and were friends with people who shaped the music scene. How many people can say the guys from Kraftwerk did the visuals for their first recording!

Music was always around in the factory. There was a girl living there [Esther Friedman] who was dating Iggy Pop. When I was playing music, I wouldn’t dare consult a big star like Iggy or David — it was just for fun. Ambient electronic music started in Germany. America had pop culture, but in Berlin, musicians found their own style. I was doing stuff with my friend; I started my own label. I did an EP recording with Manuel Göttsching, “Ich bin a Domina” (I Am a Dominatrix).

I worked on that for three years and then felt like I had to decide between fashion and music. I decided I was a music consumer and not a music maker. My fashion shows always had live music. I had friends “translate” the vibe I imagined, and they’d interpret it their own way.

Which other designers you are intrigued by?

Eckhaus Latta — I see a lot of similarity to how I was when I was starting out. And they also do a lot of knits. I used to love Pierre Cardin; he put modernism into fashion at the time. And Rudi Gernreich. Today, I like JW Anderson for what he does for Loewe. Big brands aren’t too interesting for me. Big houses work with young designers and kind of envelop them. I mostly look at other designers for what not to do — because it’s already out there. My big challenge is always to do something that hasn’t been done in that way before.

Having been in the business for so many decades, how do you feel about the resurgence of certain aesthetics? Are they part of a natural cycle or are they facile references?

I’m a modernist. I want a modern style, one that doesn’t look back in a nostalgic way. As a consumer, I prefer real vintage as opposed to remade vintage done by big brands. I’m very much inspired by architecture and artists working now and the materials they’re using. There are changes in terms of the knowledge of how to make fashion, like the approach of Iris Van Herpen, whom I like a lot. But I’m too old to think about new inventions. Me, I’m still using my hands.