Textile designer Constança Entrudo describes her homeland, Portugal’s Madeira Islands, as a colourful place. “Once you live there, you start to realize that the colour combinations are quite odd,” she explains, describing the idiosyncratic manner in which the region’s inhabitants dress, the vibrant flora and fauna, and the seemingly “random” hues of the island’s post-modern architecture. A quick Google Image search showcases land and seascapes of Atlantic turquoise, Strelitzia orange and Erythrina fuschia; coastlines dotted with terracotta rooftops, smooth stone buildings in marigold yellow and cobalt, fishing boats in reds and blues. As Constança alludes, it’s a beautiful clash. And it’s one that heavily informs the vibrant, experimental designs of her namesake fashion label: textile expanses where many diverse hues, prints, patterns and textures abound.

Born in the aforementioned Portuguese islands, Constança lived most of her life in Lisbon before moving to London at age 17 to pursue art. After a year there, she enrolled in Central Saint Martins’ Textile Design program, drawn to its fluid approach to both fashion and art. It was during the latter half of her studies, while specializing in print design, that Constança developed the unique textile-making approach that would come to define her practise. Focusing on creating prints — “surfaces” rather than fabrics, explains the designer — presented a much more free manner of making materials, not bound by the machines of knitting or weaving. For her graduate collection, Constança created a fabric made of bonded threads, unrestrained by the standard warp and weft of woven fabrics. “It started from the material and it grew into this larger concept of being a brand that resists any kind of restricted framework,” she explains.

In 2018, Constança showed her first runway collection at Lisbon Fashion Week. The offering extrapolated from the designer’s graduate collection with deconstructed shirting and suiting, frayed madras checks and jacquard beach stripes, ‘unwoven’ tube tops and dresses. The showing was met with much acclaim, and after a stint as a textile designer for Balmain’s haute couture department in Paris, Constança returned to Lisbon permanently to focus on her own label.

Guided by what the designer describes as the “very intimate connection” she feels with the materials she creates, Constança’s label foregrounds the world of textile, and all that that entails. “Colour plays a very important part in my work,” she says. “And in textile that’s something you can develop in so many ways: through dyeing, through the combination of materials, through manipulation.” Recently, the designer developed a heat technique that creates a fading effect, another way of playing with saturation.

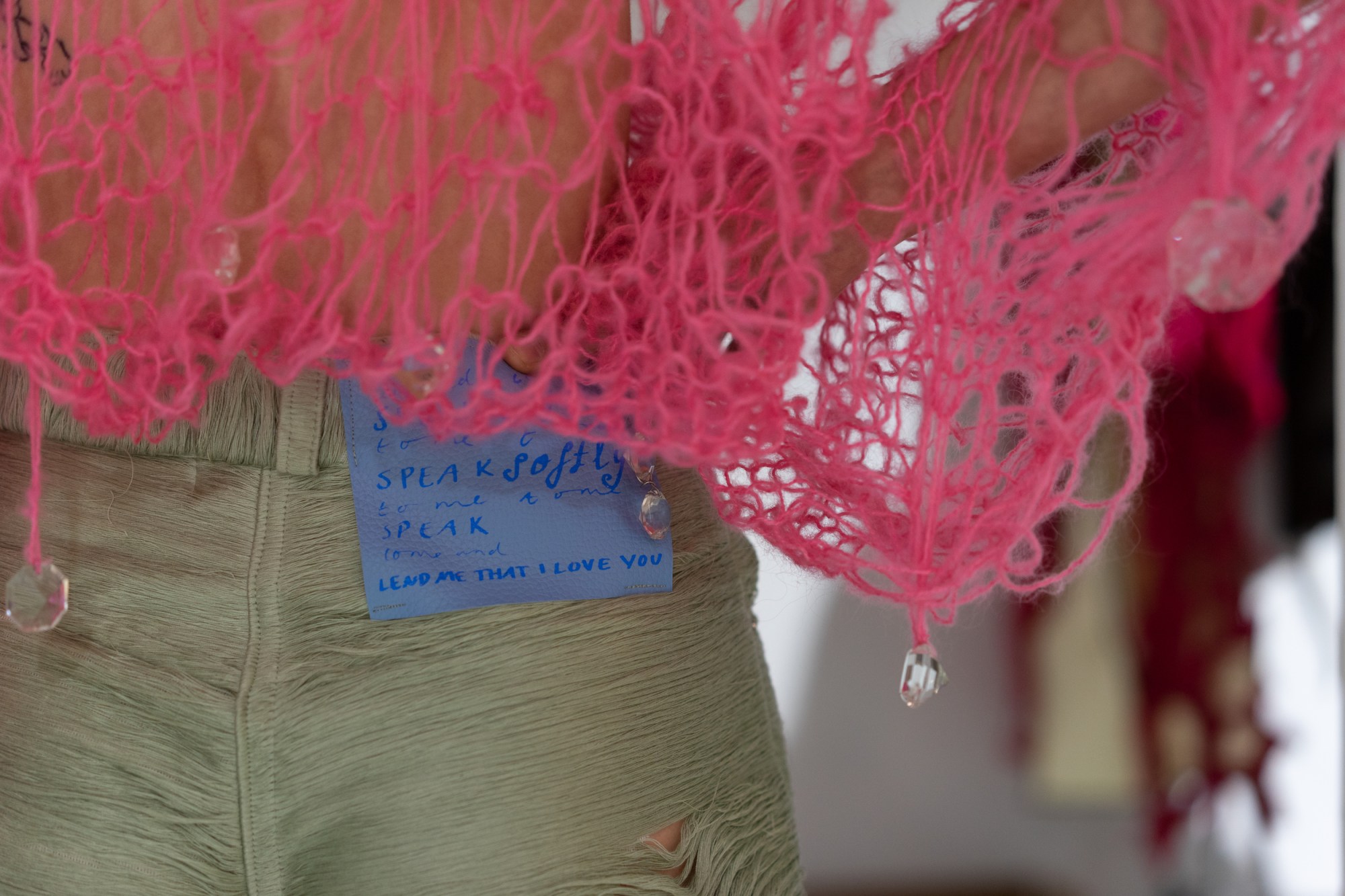

The concept of ‘play’ informs Constança’s practice in a secondary way, as well. “[My label] is about bringing humour to fashion,” she says. “Fashion is always taken in such a serious way. When I’m creating, I’m thinking that I just want people to feel free — to take themselves less seriously and have fun.” Constança cites Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel and Margiela as touchstones; the designer’s garments are imbued with the same surrealist, mischievous energy. “I like to create illusions in my work,” she says. “The idea of ‘trompe l’oeil’ — tricking the eye — is something I’ve been developing since university.” One of the label’s hallmarks is a series of ‘creased’ fabrics, which, upon closer inspection, were printed to look as such. For AW21, the designer developed a series of ‘cable knit’ garments, some of which were not knit at all, but were woven and embroidered to create the appearance of knitted cables.

The unique way in which Constança uses textile to disrupt, to evoke delight or to tell a story, is best exemplified by the label’s Trompe L’Oeil Dress. Conceived for a laugh during a lunch break in one of the designer’s knitting factories, the dress features a life-size image of the naked female form, sourced from a nude calendar belonging to one of the factory’s workers. “[At that knitting factory], they do this jacquard technique where an image is translated exactly like a photograph,” she says. “I was like, ‘Just for fun, let’s try this and make a fabric.’ We printed it and had a laugh, but in my mind I already had the idea for the dress.” What began as a fun, off-the-cuff experiment has become one of Constança’s best selling — and most viral — styles to date. It’s easy to see why: the explicitly photo-real garment conjures the shock and awe of the naked dress, with a playful wink. “[The dress] really represents what I stand for. It represents being brave as a woman,” she explains. “At the end of the day, it’s just a body.”

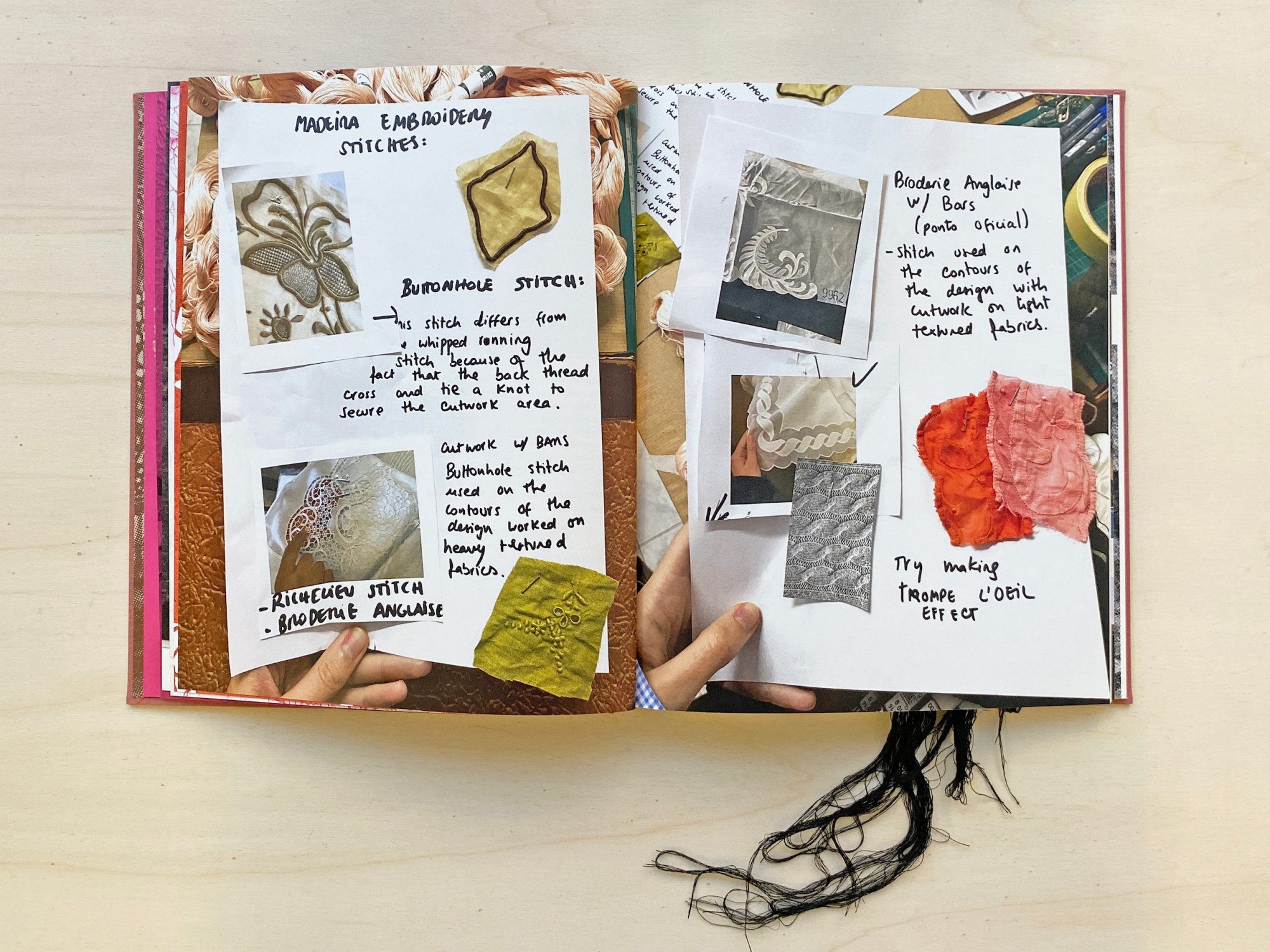

For her AW21 offering Constança confronted gender roles, albeit from a different perspective. The designer collaborated with the Madeira Institute of Wine, Embroidery and Handicrafts, renowned for its fine embroidery technique utilized by French couture houses like Chanel. “I’ve always had an issue with embroidery, in a way, because I always thought it was a gendered technique: how only women were embroidering, how they were all doing it from home,” she says. “But this collaboration changed my opinion about how I see embroidery in the 21st century. The whole collection was finished and embroidered in Madeira.”

Titled ‘The World We Live In, Part 2’ the AW21 collection itself, like many others last year, drew inspiration from the pandemic’s quarantine lifestyle. The season’s offering of coats, pants and dresses were printed and embroidered with photographs of sparse, human-less landscapes and sea-scapes, sourced from a vintage issue of Life magazine. “We were indoors and we were wearing what we were looking at: a deserted world.”

The designer developed the idea for the season’s virtual presentation from a poignant, early-pandemic Guardian article, titled “We Are All Edward Hopper Paintings Now”. “It’s exploring the passage of time but the idea of staying in the same place. The whole idea of the lookbook was that the models were all in the same spot, but time was passing and things were evolving. It was also about the idea of loneliness in modern life,” she says. “[Edward Hopper] depicts people in restaurants or hotels, looking out of windows and just thinking, and we wanted to recreate one of his paintings.” In the beautiful, surreal photographs, shot by photographer Igor Pjörrt, models stand in the threshold of a giant window as dawn turns to dusk, again and again. In one shot, the glow of moonlight illuminates a string of glass beads, the halter strap of a patchwork dress.

For SS22, Constança was inspired by the concrete poetry of the 60s and 70s. Artist-poets like Ilse Garnier and Cecil Touchon who explored typography as art form. To realize the collection, Constança tapped multi-disciplinary artist Isa Toledo to create a series of abstract poems which were then transformed into colourful prints. Across the offering, strings of words spill from the collar to the hem of a jersey gown; phrases turn and twist themselves around the body of a dress until they’re illegible; unwoven fabric trousers whisper to the written word, the page of a book fed through a shredder. On the jacron label of a skirt: a poem, written in curly aquamarine. “It’s funny because all my references this season were in black and white,” she says, referring to the textual works of Garnier and Touchon. “But in the end, the collection was really colourful.”

This season also marked Constança’s Paris Fashion Week debut. After a series of virtual shows, it was an opportunity to realize an installation-based presentation that had been percolating in the back of her mind for some time. “I wanted to create a whole world, a whole space for the models to inhabit. I designed a set made with layers, which is something I use a lot in my textiles and garments, so I thought it would make sense that the models were hidden in layers and [the audience] would have to go through them to discover [the clothes].” Constança presented her colourful offering among a series of undulating corrugated structures at Galerie Joseph. This time, beneath the gallery’s skylight, the designer’s signature glass beading was lit up not by a digital moonbeam, but a real ray of sun.

“This year the brand grew a lot,” Constança says. “We didn’t expect that to happen because of the pandemic.” But despite the textile designer’s success in the world of fashion, she doesn’t want to limit herself to a single discipline. “I’m also an artist; I want to be in the same conversation as artists,” she adds. “I want to create clothes that maybe you won’t wear everyday, but that you feel special about and you really value. She recounts how, recently, an art collector purchased a pair of her trousers to display as a wall hanging. It’s a prospect that excites her. “We should see clothes with a more fluid perspective.”

Credits

All images courtesy Constança Entrudo