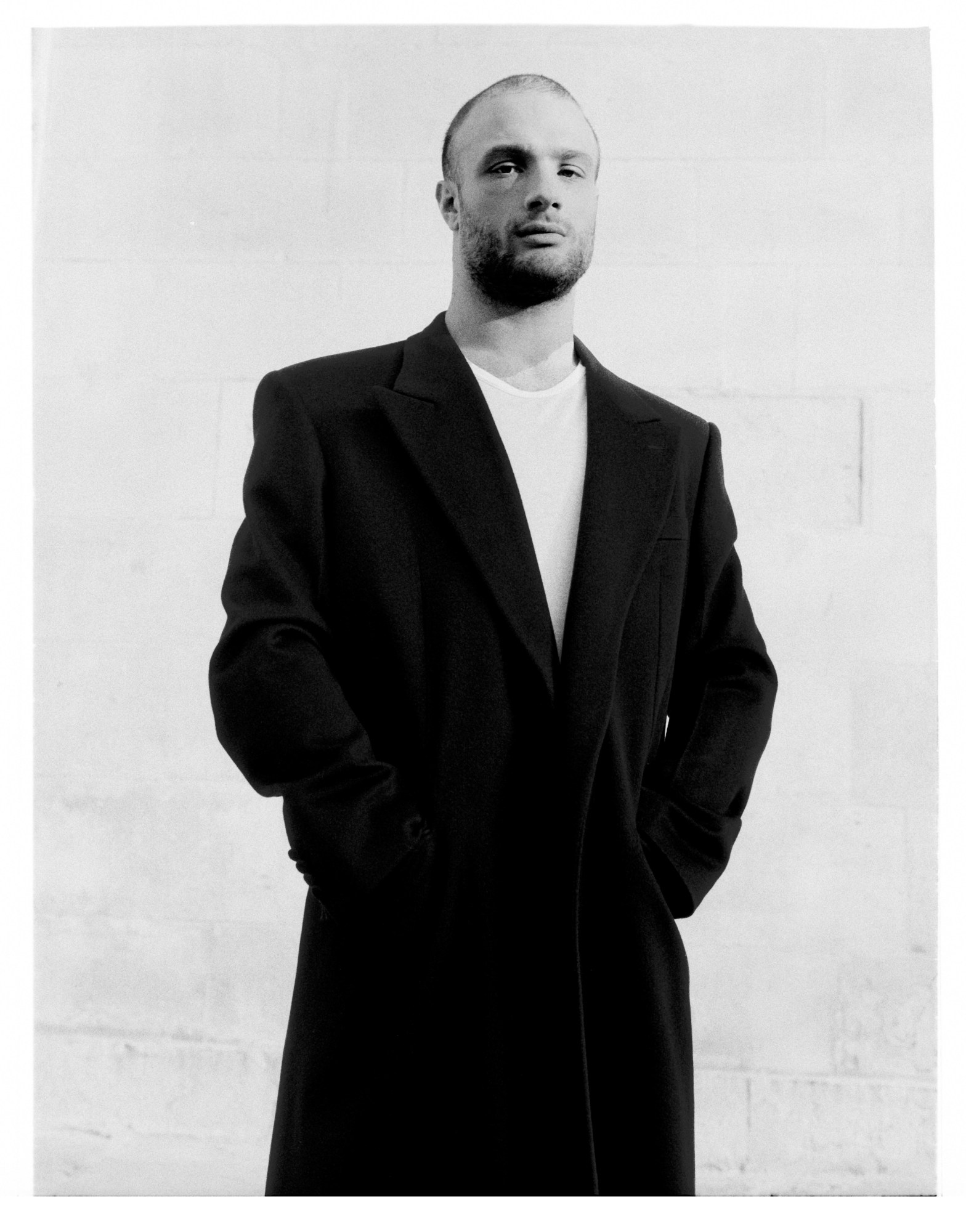

In March 2020, i-D met Cosmo Jarvis to discuss his role in ‘Calm With Horses’, when this article was originally published. Cosmo Jarvis will next star in Netflix’s ‘Persuasion’ on 15 July.

Cosmo Jarvis is stuck in limbo. “It’s that purgatory period where you’re waiting for every project to realise itself,” the British actor says, drinking a coffee in an east London cafe. He’s just shot four projects in quick succession, and for the past few months, has found himself with much more free time; a reality for most actors who favour interesting, independent work over a-million-arses-in-seats blockbuster movies.

When we meet, he’s just returned from the Sundance Film Festival, where The Evening Hour, an American indie about a small town drug dealer debuted. A fortnight from now, he’ll be at the Berlinale with Funny Face, in which he plays a brooding young Brooklynite who adopts a secret persona and stages an anti-Capitalist fightback against a big city kingpin. He’s been sitting and waiting patiently for these films to bow; eager to get out and talk about them.

Calm With Horses, which will be released in UK cinemas this month, is his first major movie role since his breakout opposite Florence Pugh in 2016’s Lady Macbeth. After that film’s release, he was dubbed a sparkling new star in British cinema, destined for greatness and wider fame. But the immediate impact of such high praise for most is an awkward segue from indie filmmaking into the glossy echelons of popcorn cinema; a knee-jerk transformation from a modest actor to sizzling, costume-cladded superhero. Cosmo Jarvis, respectfully, doesn’t care for those roles.

It says a lot about his patience that he didn’t automatically vie for something overly grandiose to follow Lady Macbeth, instead waiting patiently for something worthwhile to come along. Calm With Horses feels like a perfect vehicle for his talent. Set in a rain-lashed and grey contemporary Ireland, it tells the story of Douglas, nicknamed Arm: an imposing — if highly sensitive — former boxer, who since retiring from the sport, has wound up becoming the henchman for the notorious drug-dealing Devers clan in a pokey town in west Ireland. The gang become his de facto family since his fall from grace; handing him an income to help support his young, autistic son and ex-girlfriend, albeit through violent and destructive jobs he’s forced to absorb the blame for. In it, Cosmo is electric; an unyielding take on a supremely flawed character. Critics have compared him to Marlon Brando.

“At the time I was, like most actors, ready to fucking quit at any moment,” he says. “Because [the industry] is such a seemingly monstrous entity to conquer and realise. The script came through and you could tell how specifically Joe [Murtagh, the film’s screenwriter] had crafted this language. It was incredible and tied to its own environment.” Arm, though his situation is fairly singular, represents the kind of inner turmoil many men will deal with, their vulnerability and masculinity battling it out. “The arc of Arm himself, and question of where his head lies in terms of loyalty? These are all things we battle with all throughout our lives,” he says. “With everything I go for I try. But with this, I really wanted it.”

After securing the role, he gained weight and worked out — to make himself look “imposing” — and moved to County Clare a month before filming. There, he did “as much hanging around and conversing with people” as he could. “I’m fairly used to living out of a bag, but it felt like a brief migration to a place that was a gift to witness and be a part of.” When the cameras started rolling, he mastered the accent and assumed character, not dropping it until the day the film wrapped. The production team, most of whom were Irish, had no idea he was from Southern England throughout the month-long shoot.

On the surface, the performance — peppered with scenes involving gunshots, fist fights and heads shattered through glass tables — was an arduous experience, especially considering Arm is, underneath, far softer than his actions. How did Cosmo deconstruct that? “The beauty of it was that it was actually really easy,” he says, drawing out that last syllable into a light, satisfied groan. “I’ve witnessed the consequences of when the minimum level of perceived empathy isn’t reached by people. I’ve been privy to the miscommunication of empathy versus obligation — that side of it was easy to understand.” Instead it was the ways in which he and his character differed that forced him to analyse himself.

“When I’ve come into contact with [those situations], I over analyse and try and take it apart in a pseudo-academic way, but Arm isn’t that sort of person. He’s unable to look at it from a more withdrawn point of view,” Cosmo says. “You’re witnessing a man coming to terms with [his actions], albeit a little too late. You know that from the beginning. If I had seen a film like that growing up, I certainly would have allowed it to inform how I thought about my own life.”

It’s interesting to consider the changing face of the male cinematic role model. Ten years ago, a character like Arm would’ve been celebrated for his brute strength; framed, by some directors, as a statuesque, Statham-like figure of power. From the start of the film to its gutting final minutes, Cosmo creates a character that looks like this, albeit broken inside. Does he find roles that complex come up for men more often nowadays?

“I think it’s a tricky time for male roles because people don’t want to see men in the way that…” his sentence peters off. “For example, Han Solo wouldn’t have been presented in the way he was back when I came to love Han Solo, because he’s a scoundrel. Scoundrels are no longer politically correct, so I guess there’s been some adjustment in terms of how men will be portrayed in film.” He’s right, in some ways. The separation of art from reality, and depicting someone’s actions versus flat out condoning them, is a complex situation to make sense of. Men, who’ve been reprehensibly throughout cinematic history but always given a free pass for their behaviour, now are faced with an interesting challenge. The DNA of their character is shifting.

“Right now, I’m just taking what I can get as it comes and being grateful for it,” he adds. “There’s been such an influx of cultural and technological happenings that if something comes along and it’s good, then I’ll do my best to do a good job. I know what that is when I see it.”

For now, Cosmo Jarvis is balancing this path to the future while reckoning with those Brando comparisons, which he’s laughing off a little: “What an outrageous thing to say!” he grins. With all of these films lined-up, it’s set to be a busy year for the actor; loaded with possibilities and praise. Has he had time to think about what he’s learned? A revelation, perhaps?

A few seconds pass before he utters a response. “What, a revelation?” Another few go by before he musters up an answer, starting and stopping. “All you can really do is the best you can in the minute,” he says. “And realise that any projections of the future or nigglings of the past are deadweight. It sounds fucking obvious but I still haven’t realised that. I’m just trying to implement it now,” he says with a half-smile. “Slowly.” And with that, he’s out the door and off home, back to a life — though not for much longer — in languorous, temporary limbo.

‘Calm With Horses’ opens in UK cinemas on 13 March 2020. It will also play at Dublin Film Festival and Glasgow Film Festival on 5 and 7 March respectively.

Credits

Photography Scott Gallagher

Styling Louis Prier Tisdall

Grooming Petra Sellge