In July 1975, film director William Friedkin — two years after his massive box office success The Exorcist — attended a film class at Manhattan’s New School as guest lecturer. He recalled his research methodology for the room of burgeoning, dewy-eyed filmmakers. For 1970’s The Boys in The Band, William’s first gay-themed movie, he took a pilgrimage to New York City’s own gay mecca: Fire Island.

He specifically recalled The Meat Rack, an infamous outdoor cruising spot: “It’s a gigantic pit with 200 to 300 guys in a daisy chain balling each other in the ass. One guy got close to me. He said: ‘I think you’re cute,’ and I turned around and got out of there as quick as my legs could take me.”

A voice cried out from the crowd: “No wonder your movie was so lousy!”

This was journalist and queer activist Arthur Bell, one of the twelve founding members of the Gay Activists Alliance. Bell had written his first article for The Village Voice in 1969, covering the Stonewall Uprising. He began a regular column for the Voice in 1976, “Bell Tells,” in which, with an infamous combination of bombastic charm and personality, he would cover nightlife and show business in New York City.

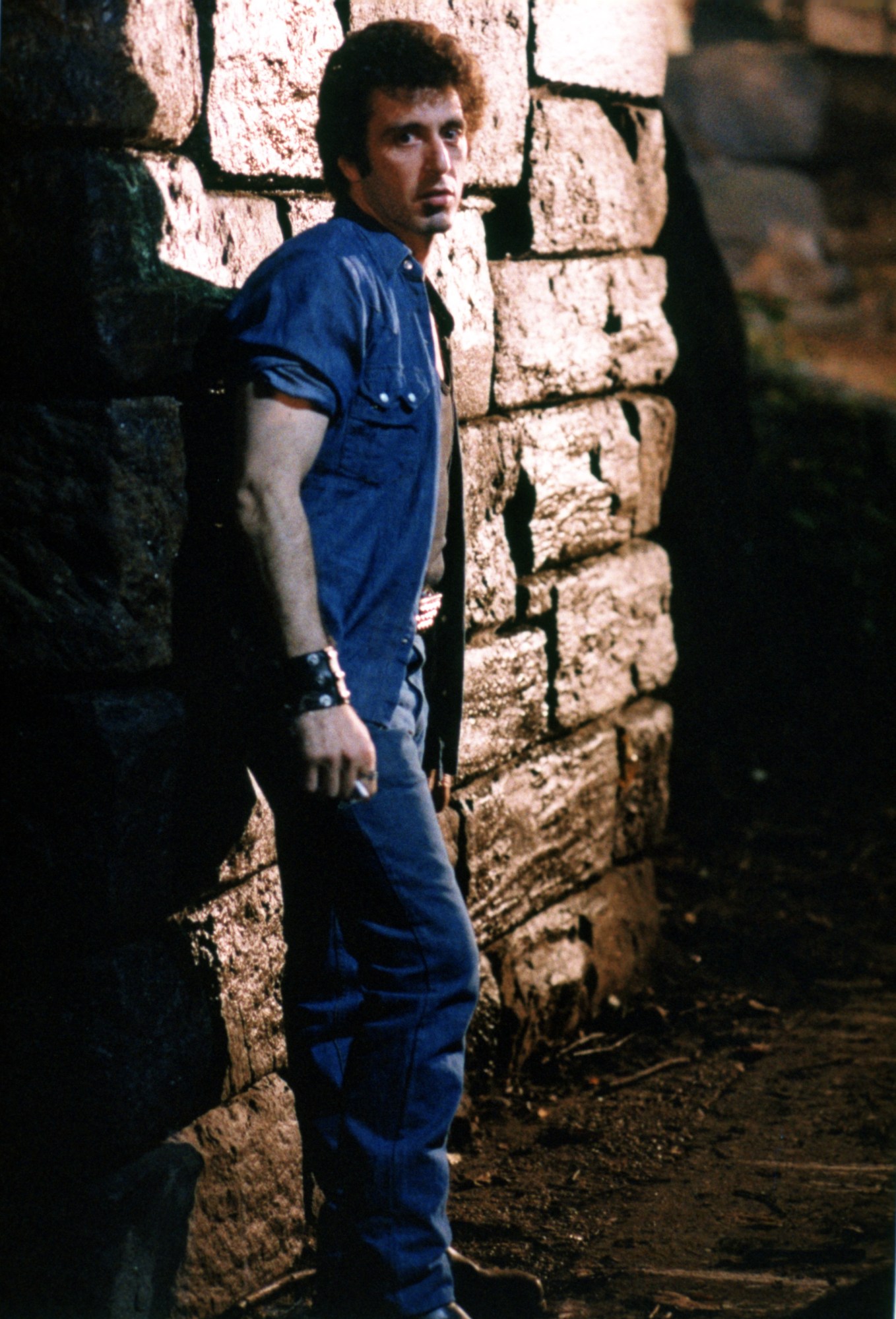

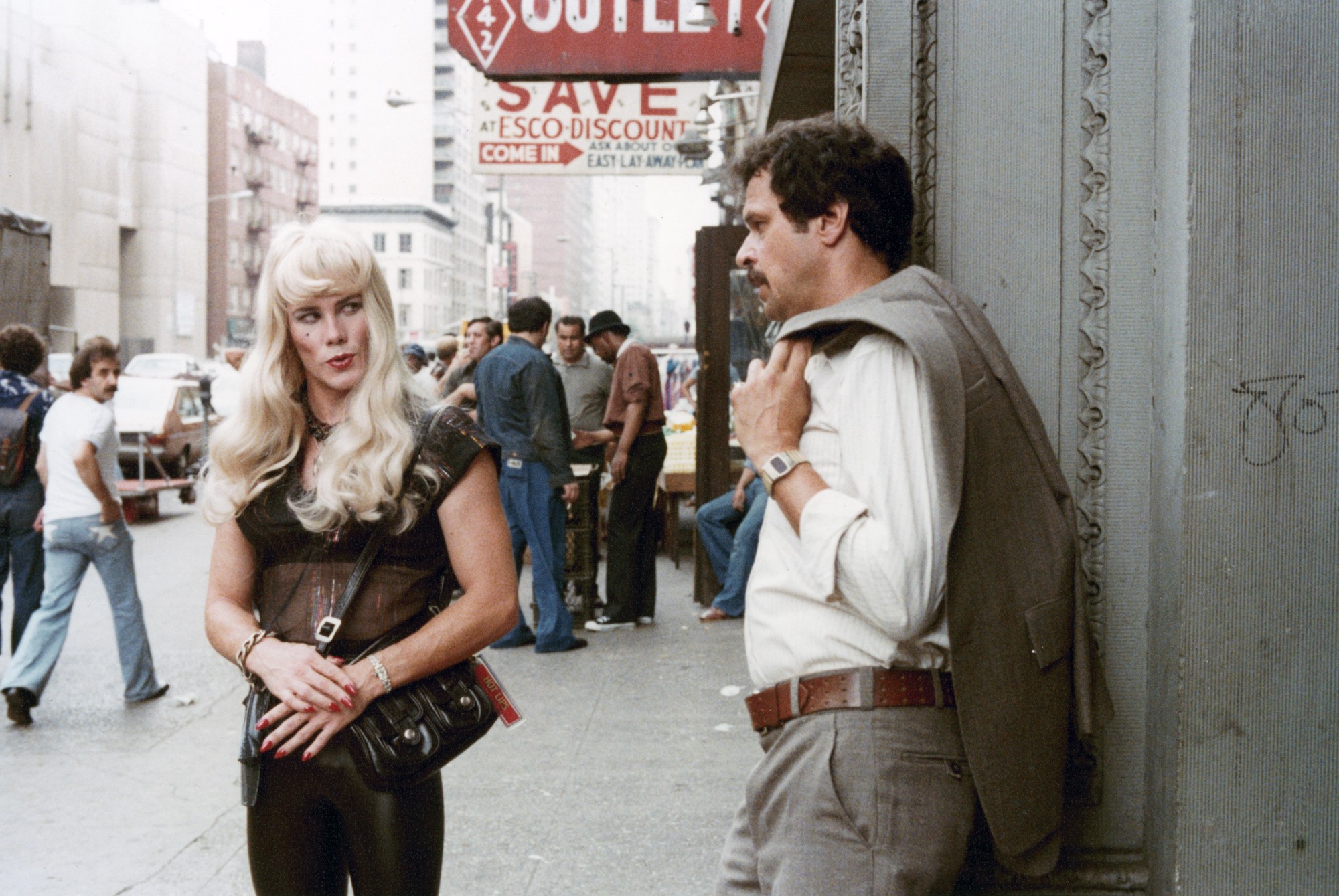

Five years later, and William had announced production of his next film: Cruising, a slasher flick starring Al Pacino and set in New York City’s sordid gay underground. It would be the first film to bear witness to the hedonistic leather scene of the city’s meat district: poppers, used hankies and all.

In the 16 July edition of the Voice, Arthur’s column decried the film as “the most oppressive, ugly, bigoted look at homosexuality on screen,” and “a validation of [anti-gay rights campaigner] Anita Bryant’s hate campaign”. Acting as “the godfather of the gay movement,” as he would later self-describe, he called on the city’s gay community to organise.

By 25 July, several hundred demonstrators had mobilised against the film. And after Mayor Ed Koch denied the National Gay Task Force’s demands for Cruising’s shooting permit to be revoked – on the basis that there was no reason for filming to be halted when all legal and safety guidelines had been met – the protests snowballed into the thousands.

“I remember those protests,” Randy Wicker, a veteran of the gay liberation movement says. “They were mainly composed of [Gay Activist Alliance] activists. As I recall, they used a lot of whistles.” The Gay Activists Alliance popularised the “zap,” an in-your-face tactic of direct action that contrasted with the peaceful picket lines of other gay rights groups. This included, as Wicker describes, whistle blowing on the fringes of Cruising’s production line.

“The idea for ‘noise disruption’ came from the reality that it was physically almost impossible to get to the filming because of police barricades,” Randy adds. “Noise interruptions supposedly cost [the production] something like 30 thousand dollars an hour… so that was their main technique. It could have been an exaggeration, but it was effective. We knew we couldn’t stop the film, but we could ‘make them pay’ for presenting a bad image of our community.”

Craig Lucas, who would go on to write the first ever theatrically-distributed film about the AIDS crisis, Longtime Companion, was a struggling young writer in the Summer of 1979. “I was scrambling to make enough money not to be evicted, and in every waking moment when I wasn’t painting apartments, I was trying to write my first play – I was kind of a hermit,” he explains.

It was at the height of Craig’s financial problems that William Friedkin came knocking. Craig’s was one of the scenes shot earliest, so he wasn’t aware of the burgeoning protests against the film. “I guess I knew enough about gay liberation to be able to improvise dialogue as an activist complaining to the mayor about the NYPD,” he says. William’s motivation, Craig suspects, was to reactively incorporate aspects of the debate around the film’s political soundness (or, rather, lack thereof). I was certainly an out gay man, which I am guessing is why William was willing to cast me. By the time I woke up to what was at stake, I’d shot my scene and then I was just wishing that I hadn’t been a part of it.”

A considerable schism in the Cruising debate centred on the filmmaker’s freedom of speech: weighing up William’s right to make Cruising, ethics be damned, against the gay community’s right to mobilise, and asking to what extent their actions could be considered censorship.

On 26 July 1979, long-time gay activist Ethan Geto, speaking on behalf of the National Gay Task Force, demanded that “the Mayor respond to a large segment of his constituency and withdraw the support of the city.” In the view of the NGTF, the demand wasn’t for censorship, It was for humanist tolerance and respect.

“I objected at a Gay Activist Alliance meeting, saying that I did not believe in censorship,” Jim Fouratt, a co-founder of the Gay Liberation Front says. “I did believe an artist has the right to free expression, and to suffer the consequences of that expression as long as there was no physical harm intended as part of that expression. I remember Vito Russo supporting me that night.”

Protests would continue in force throughout the months of the film’s production, and renew on the steps of movie theatres when the film was released. At one demonstration, on the evening of 21 August 1979, Jerry Weintraub — the film’s producer — was struck by a thrown bottle.

“One morning I was awoken by the sounds of pots banging and loud whistles, as GAA members were disrupting the shooting of the film on the block I lived on,” Jim continues. “I went to my bedroom window and watched this ugly action of self-righteous anger. Politically correct censorship — an attempt to censor creativity.”

Cruising was eventually completed, although approximately 60% over budget, mostly owing to the “zaps”. It screened nationwide from 8th February 1980. The controversy surrounding the film’s production would contribute to a lacklustre performance at the box office.

“I wasn’t living in New York at the time, but I remember the controversy,” Jeffrey Escoffier, the co-founder of The Gay Alternative, a gay culture magazine in the 1970s says. “To some extent I think the ‘political’ significance of the movie has changed. I’ve also heard younger gay men say that it helped them to come out. Apart from whether or not it was homophobic, there are also some other interesting aspects to it: it was incredibly explicit about gay sex, and the visibility of gay male sex through the city gives it a kind of historical value.”

The protests should never be denigrated — Cruising was released just a decade after Stonewall, during a time where few legislative rights or protections were afforded to queer people. Anita Bryant and the Moral Majority made sure of that. And the film, made for a mainstream (read: heterosexual) audience, manifestly exploited the ‘risqué’ gay community for profit.

But what the past 40 years have allowed for — past the AIDS crisis, political hurdles, and the progressive wave of tolerance towards gays in the West — is a renewed analysis of Cruising. It best exists today as a historical snapshot; a celluloid relic of a community long forgotten.

This piece was originally published in 2020. We are republished it in the wake of William Friedkin’s death.