Within the last decade, Lagos went from just any other city to one of the most inspirational creative hubs in the world. One of the exciting names the city has to offer — and competition is stiff — is multidisciplinary artist and creative Daniel Obasi, who’s been doing graphic design, styling, photography and filmmaking in the last five years alone.

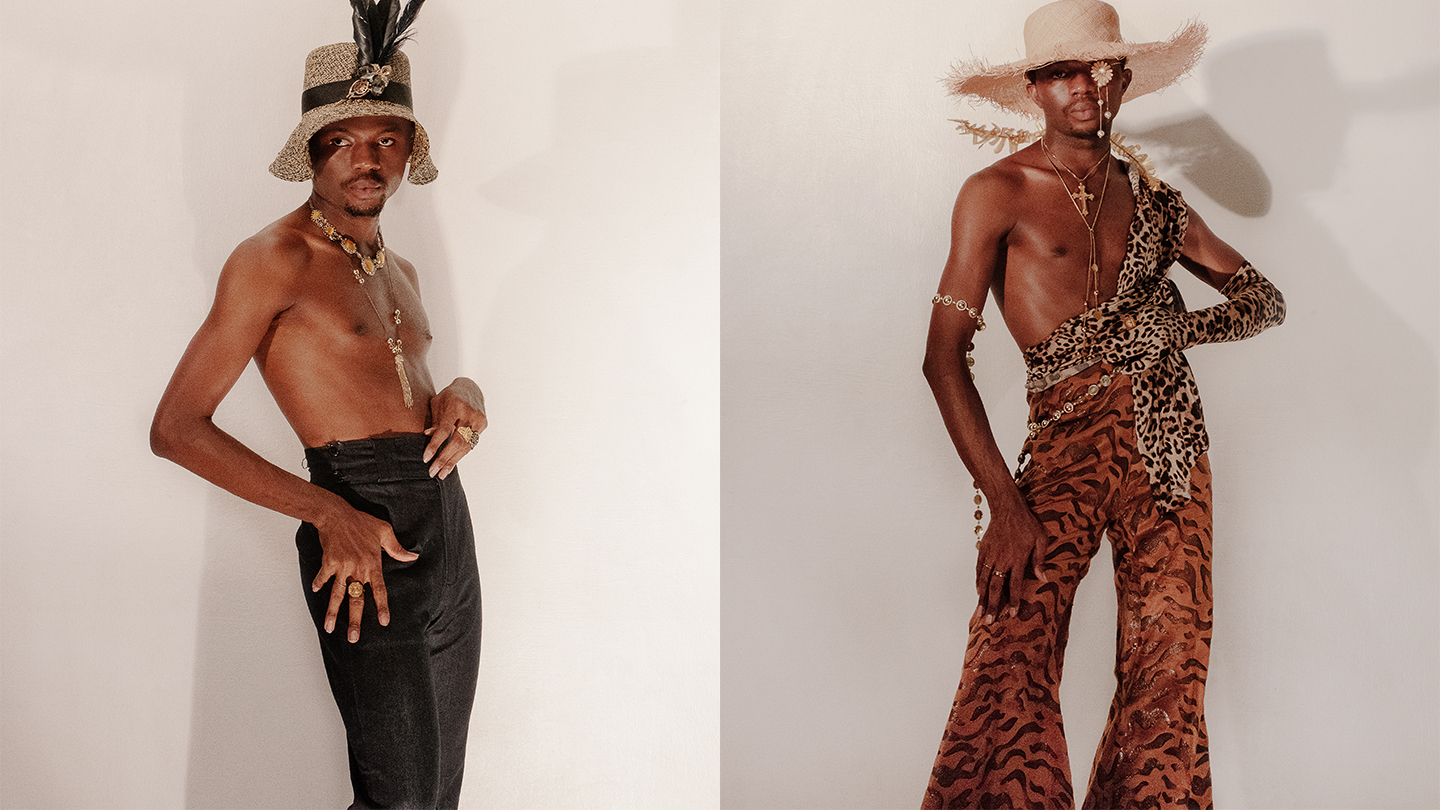

Deeply concerned with advancing African narratives through creativity, Daniel’s work is a heartfelt ode to the country that raised him, turning the good and bad into visual poetry by using the medium of fashion. Whether it’s styling music videos, creating beautiful self-portraits like the ones he’s made for i-D today, or exploring sexuality and masculinity, his unique narrative and approach create its own universe, one that you’d happily lose yourself in.

But like many creatives across the world, Daniel’s practice and lifestyle has been completely transformed by government mandated coronavirus lockdown. We caught up with him as he hunkers down in isolation to talk staying creative and world building when the world is closed for the foreseeable.

How have little creative practices like self-portraits and writing helped you keep sane during lockdown?

I mean the whole pandemic hit us all pretty hard, and by surprise of course, and just a few weeks after I had returned from a film festival in Berlin everything began to lock up. I guess the only positive thing would be that it has given me a little bit more time for myself. I have always enjoyed being a muse and with the past year spent on working on different projects I got some free time to perform in front my camera.

It’s been mentally refreshing and a welcome distraction from the horrid news that we‘ve been bombarded with weekly. I had some ideas that I wanted to write about and possibly create but never had the time and patience to see it through, but now I do. I can look through all my scattered notes and finally begin to pull bits together into one body of work. I have no idea where this particular work will lead to or what it will look like eventually but it just feels good to escape a little.

What made you want to become an artist?

I was really introverted growing up in Lagos and Aba. When I got to primary school my mum decided we should move back to the east to be closer to our heritage, and we moved back to Onitsha. I lived there for three years. While I was there I felt this overload of fashion for the first time because Igbo people are so extra, but it didn’t click to me that it was fashion per se, it was just something I found very interesting. My landlord, for instance, had seven daughters and every Sunday they’ll go out dressed up. It was all interesting and colourful. All of that was registering in my subconsciousness.

How did you develop your visual practice as a photographer and filmmaker whilst also working as a stylist and designer?

I embraced photography out of necessity — because there weren’t a lot of photographers in Lagos who could shoot the way I wanted to present an image. Same with filmmaking. I always liked the idea of experimentation and I also noticed that the kind of visuals I was trying to create weren’t really popular. It wasn’t something I could explain to a director and they won’t get it, so I was like fuck it, I’ll direct it myself. I made a lot of mistakes along the line but I’ve learnt from them. Making these little clips and personal projects kept building up to me taking on an entire film project. When I look back at the projects I’ve done, I still don’t feel I’ve scratched the surface.

How would you describe the world you build through your practice and projects?

When it comes to world-building, I always like the idea of existing in a time loop where you’re drawing inspiration from the past, present and future — something that some people may refer to as Afrofuturism. We live in a society that’s toxic, evil, very judgemental. The worlds I am imagining touch upon these problems but come from a place of no judgement — it’s a place where one can reflect on politics without being afraid of speaking up; a place you can reflect on sexuality without being afraid of being judged; a place you can talk about gender roles without conforming; a place women are powerful and men can be vulnerable. I try to elevate the position of the oppressed and create the visual scape that allows you to be free to exist.

What’s your perspective on the global attention African fashion has been having in the last few years?

It’s complicated. There’s a huge African American conversation right now concerning the diaspora; the need for identity, the growth in the music scene — it’s a lot of different things and all of it has drawn attention to what’s going on back home. African fashion has always pushed for a seat at the global table. Luckily things have started evolving and a lot of black gatekeepers in fashion have begun to pay more attention to where they come from. While the industry here is not so so big, underground it has been preparing for global attention for a couple of years now. It was perfect timing for us and we were ready to expand.

In saying that though, I for one don’t think our industry is sustainable yet. We haven’t really invested in our local markets yet because a lot of the time we are focussing on exporting the fashion. This makes us neglectful — we don’t have a lot of people here who buy clothes by Nigerian designers. Obviously the production and cost can be expensive but I feel it’s important for us to take a serious look at our production industry and embrace sustainability.

What does the future look like for you post-pandemic?

As for future plans, everything is really on pause for now — not a lot of jobs are coming in or out. It’s worrisome, especially for freelancers. I want to believe everything will be alright, but I also believe that change is important for the world right now. There is a lot the pandemic has brought to light, it will be a shame to just go back to business as usual in any sector.