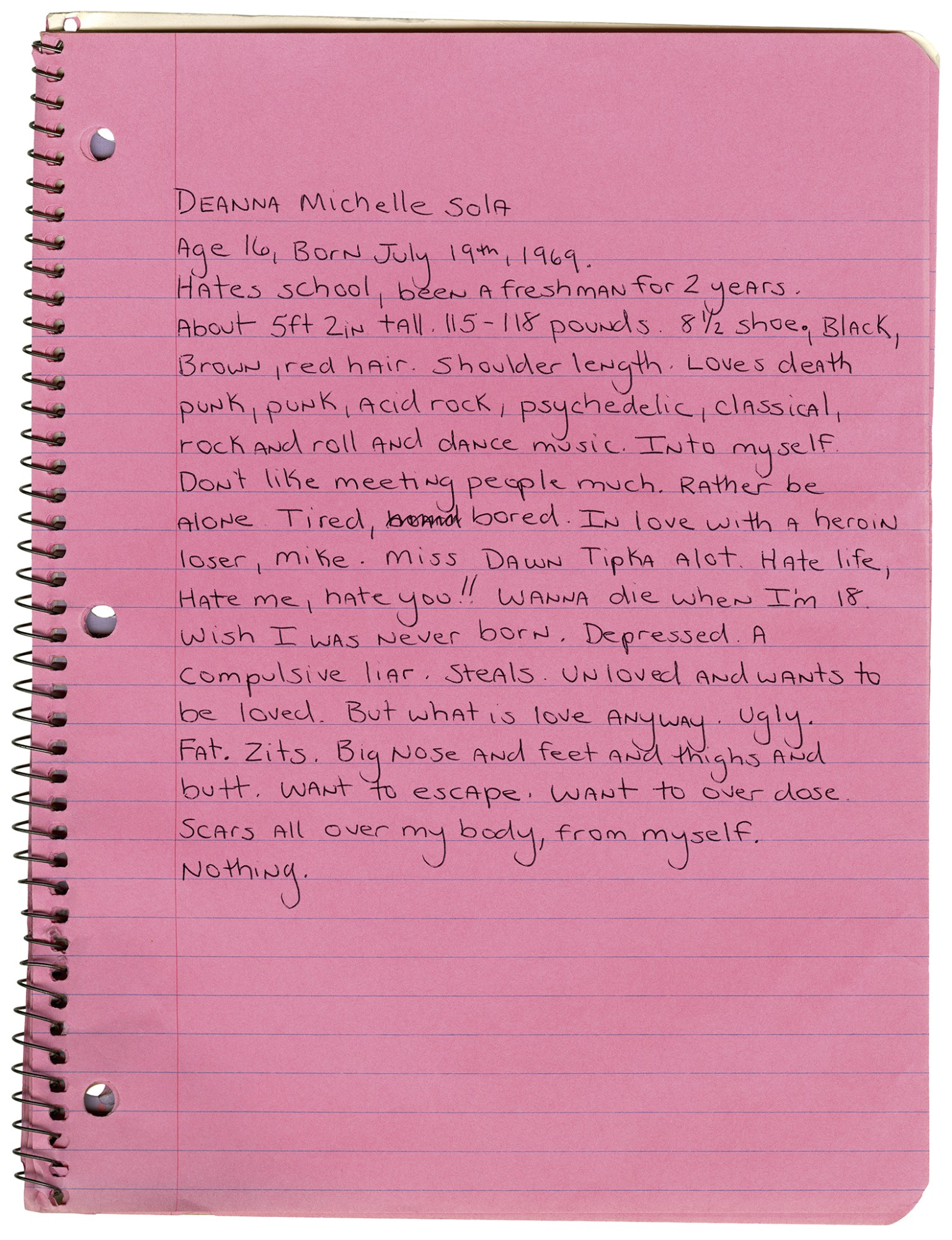

Deanna Templeton has been thinking about her adolescence a lot lately. Her new photo book, What She Said, is not only filled with dreamy portraits of young women in California, it features her own scribbled diary entries from when she was around their age. In these extracts, her teenage self ponders things like, “My face is so ugly. All my scars and pimples.” And, “I’m so tired and lazy and unhappy. I’m only 15 years old, what’s wrong with me, why am I so UNhappy?”

Back then, Deanna would sit in her bedroom in Huntington Beach, California, looking at cut-outs of supermodels and asking herself, ‘Why don’t I look like them?’ She resented the way she looked so much that she eventually started self-harming. Her solace was found in music, obsessively going to live shows to see bands like Black Flag and Bad Brains.

Her new project reflects on that period of her life, but more than that, it burrows deep inside the internal world of young women as she photographs them today. She underlines youth’s universal pains and joys — from anxieties about body image to the feverish intensity of live punk shows. Granted, when she was their age, she didn’t have Instagram or even a mobile phone, but there’s clearly a parallel between the experiences of Deanna and her subjects.

“These young women that I photographed had a lot in common,” she says. On the surface, the girls share a punk aesthetic, sure — many wear T-shirts of bands, have tattoos, etc. But it was self-loathing that emerged as the common thread. One girl Deanna photographed in 2006 had the word UGLY scrawled on her torso. “I think she might have said ‘I hate myself’ or something. I think that one had the most impact on me because I felt like what was written on her stomach was written on the pages in my journals.”

Deanna mines her memories and feelings as she meets these young women in the street. In seeing them, she saw herself at 16. “It was me, how I either saw myself or how I wanted to be,” she says. But she’s clear about one distinction. “I also want to make sure people understand that these words [from the journals] are not their words, they’re my words,” she says. “I’m not trying to project onto them. But I do feel like the photographs were able to give a visual to that time, even though they’re modern prints. But again, at least in my eye, you could quite easily pop them into the 1980s.”

To include her own journals was a courageous decision. Not only does it reveal her own vulnerability, but it created a level playing field with her subjects. She’s compassionate. She gets it. She has no ulterior motive; there’s zero exploitative artist crap.

As a photographer, of course, she was thrilled to spot these young women in the street. Sometimes she would see girls wearing a shirt with a band she saw in the 80s and start a conversation. Sometimes the girls would be at skate events where they might recognise her husband Ed, a professional skater. “I would get excited almost to the point of startling some of the young women that I’d run-up to and ask if I could take their portrait,” she says. “My mouth would be running a mile a minute just explaining like, I love your look, you know, pointing out things that I love, like their hair, or their clothes or their makeup.”

For Deanna, it was vital to show respect first. “If I approach anyone for a photograph, and I see them hesitate, I back off, because I just realise they don’t feel comfortable saying no yet,” she says. “I also knew that when I was younger, I wasn’t comfortable in my own skin to voice my opinions, to say no if I didn’t feel comfortable with something.”

She remembers one encounter from an older project where a group of girls were still learning the power of saying ‘No’. “I went up to a group of young women at a surf contest, asking, ‘Can I shoot?’ They were four really cute girls, and they were really excited, like, ‘Sure, of course!’ Then they said, ‘At least you asked; we’re having guys trying to shoot our butts all day long’. And I noticed, oh my gosh, these girls don’t realise, they could have just said no to me. They just didn’t understand the power in their own voice.” She adds: “Going through what I went through, I think helps me be more empathetic in that sense. It definitely helps me be aware of how I take portraits of people, trying to be mindful, especially for people who might not have their voice yet.”

It’s striking how emotionally direct Deanna’s project is regarding her own struggles, the lack of ego, the this-is-me frankness of it. Most of us cringe at the melodramatic words we wrote in our teens, but to publish it to the world? That takes next-level courage. I ask how it felt revisiting painful memories, how it felt to remember her insecurities. “At some points it was hard,” she says. “I’m in such a better place now than I was then that it was…” She pauses, struggling for the words. “It was just really sad to read how sad I was. Because considering I have been in a better place for a long time, it wasn’t until I sat down and re-read it all in my head… [that I realised] like how hard I was on myself. I just wish I could have given myself a break.”

I wonder what teenage Deanna would think of the project, seeing her words laid bare for the world to see. Would she be mortified? “Yeah, totally!” she says. “I would have been really scared. I couldn’t even talk to my parents when I was having all the thoughts I had. That’s the whole reason for cutting my arms; it was a cry for help.” Back then, she says, “The music spoke for me; I didn’t have the words to express the way I was feeling out loud. I could write things down, but I couldn’t actually say it with my own mouth.”

What would she say to her teenage self? First, she would hug her. “If I could have given my teenage self this little bit of confidence, we’re gonna do this; we’re gonna share this, you’re gonna be fine. This [book] is probably what she needed.”

‘What She Said’ by Deanna Templeton, published January 2021 by MACK.

Credits

All images courtesy MACK