The compulsion to buy stuff is ever-present. And it’s rarely stuff we need, really want or can afford. Consumer culture has fed us the lie that we can buy our way to happiness, leaving us forever chasing a dopamine hit that never provides any lasting satisfaction; a compulsion only intensified by TikTok churning out micro-trends at breakneck speed. In the process, it’s draining our bank balances and, as we already know all too well, doing untold damage to the planet.

A subset of influencers claim to be on a mission to right these wrongs. Among them is Jessica Clifton, a self-described ‘sustainability influencer’. Jessica sees influencers as having an important role to play in promoting better consumption habits, whether it’s through signposting people towards ethical brands (instead of the Amazon storefronts often found in influencers’ TikTok bios) or making content around “educating and inspiring” audiences, rather than always pushing products. As she puts it, “Posting hauls everyday is just bad influencing”.

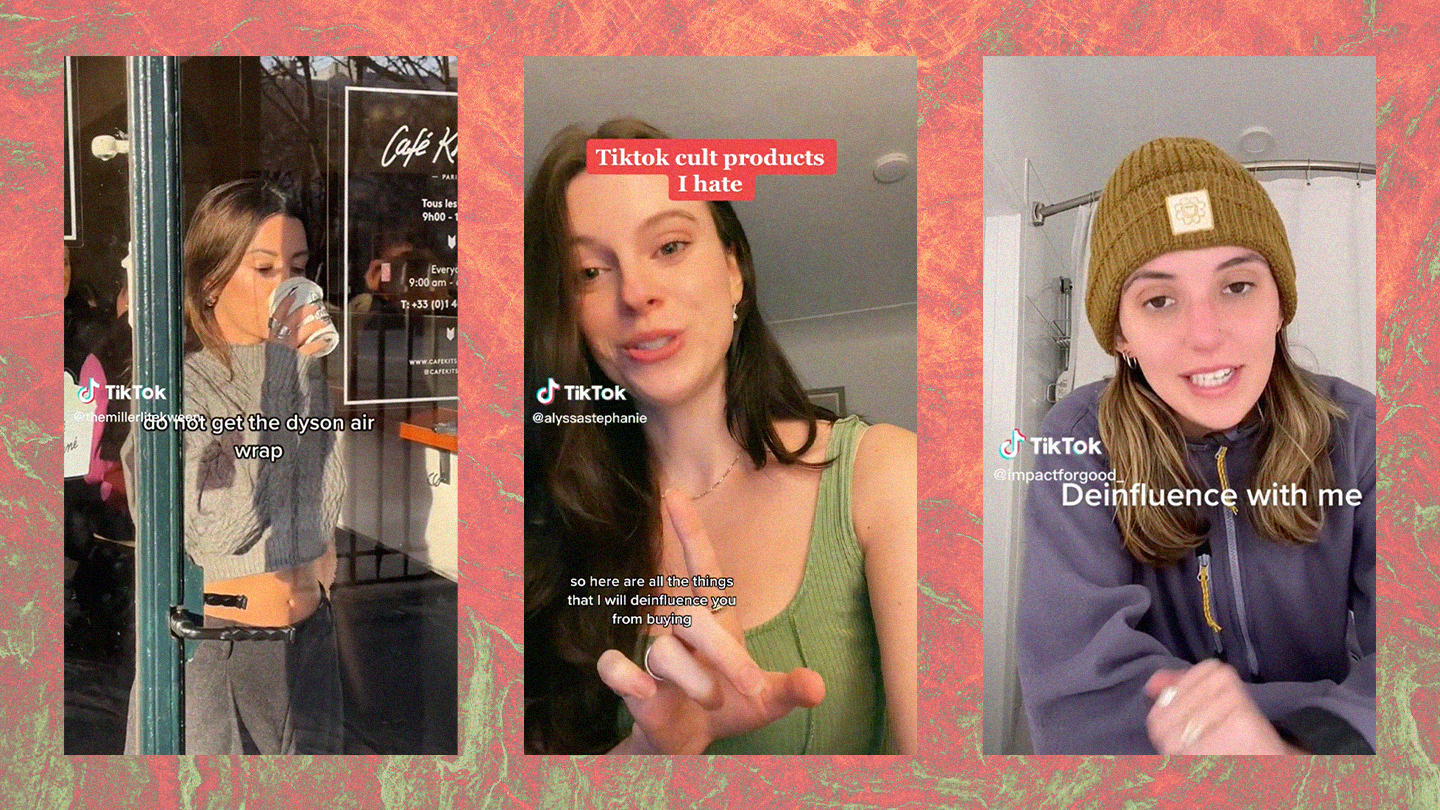

The deinfluencing trend currently sweeping through TikTok (#deinfluencing currently has 114.5m views) started off with similar intentions. Videos typically see people listing products that have blown up on the app – whether it’s the Dyson Air Wrap, Charlotte Tilbury Flawless Filter or Ugg Minis – with a simple message uniting them: you don’t need it. Jessica praised the trend in a viral video (“I can’t believe we, as a collective, are finally admitting that overconsumption has gotten out of control”) before pointing to some favoured products (“I bought the rare beauty blush, and I will not be buying another one for two years”).

Deinfluencing isn’t just about a weariness toward overly-hyped up products, it also reflects a growing mistrust of the very people pushing those products. Last month, the beauty influencer Mikayla Nogueira was subject to fierce backlash from people who accused her of using fake lashes in a TikTok promoting L’Oreal mascara. Dubbed ‘Mascara Gate’, it only added fuel to the deinfluencing fire. As Reddit user chronicallyillsyl put it: “[Mikayla] is the epitome of influencer culture: making super short videos for undisclosed ads for items she never uses again while worshipping nothing else but money.”

Anti-influencer sentiment is of course nothing new — it’s been bubbling away for a while. “We’ve seen influencer fatigue change over the years,” says Biz Sherbert, Culture Editor at The Digital Fairy. “It was first characterised by mocking the perceived vapidity of influencers but has evolved to be more aligned with an awareness of the role influencers play in forming identity around how we look and what we own. People are becoming more aware of influencers’ inherent link to consumerism.”

This raises the question: if influencing and consumption go hand in hand, can there be such a thing as sustainability influencing? The ‘deinfluencing’ trend now seems far more focused on redirecting people to ‘better’ items or cheaper dupes, therefore paradoxically still ‘influencing’ people to purchase products. For content creators, it’s become a way to tap into the anxiety of economic precarity, helping us to spend more wisely at a time when inflation is soaring, rather than telling us to actually buy less. As some TikToks have already alluded to though, by the time people have bought multiple products in the hope of finding the perfect dupe, they may as well have purchased the more expensive, ‘deinfluenced’ item.

As Biz Sherbert points out, the direction de-influencing is going means it will likely have little effect on most mass-market brands. “It seems brands who sell upmarket or expensive products will be most affected by de-influencing,” she says. “I don’t see the de-influencing trend being as relevant for brands with more affordable products that have gone viral, like CerAve.”

Jessica says she is saddened to see how the trend has evolved. “When it first came out, I was so inspired. It was genuinely about awareness… people realising you don’t need ten brushes, or that you can go through all your products [before buying more]”. But what started out as a sincere effort was very quickly subsumed by the culture of pushing products on TikTok, she says. “It became about the products that aren’t worth your money, and those that are worth your money.”

At a time when consumers expect brands to address the climate crisis, it makes sense that content creators are co-opting trends that promote sustainability. Fashion accounts for around 10% of greenhouse gas emissions from human activity, meanwhile about 70% of the beauty industry’s waste comes from packaging. According to the latest reports from Zero Waste Week, beauty packaging amounts to 120 billion units every year. Exploiting our anxieties around the climate crisis while convincing us to buy more products is nothing new, of course (see: greenwashing).

While some influencers may have good intentions in wanting to use their platform to highlight these issues, there is good reason to be skeptical about just how much power they have when it comes to creating positive change. This is particularly true of platforms like TikTok, where short-form, snappy content is favoured — in other words, not the kind content that aims to educate people about ethical consumption in any in-depth way. Platforms like TikTok, Twitter and Instagram are useful insofar that they can point people towards resources (such as environmental charities and organisations) or protests that could have a transformative impact. But influencers — who operate on platforms designed to sell us things — will always be limited in their capacity to impact consumption habits.

In this sense, ‘deinfluencing’ feels more like a catchy buzzword, one that may just come and go as quickly as the products it looks to discredit. The fact is, despite the recent backlash, influencer marketing isn’t going anywhere, with a recent survey showing that 53% of advertisers plan to increase creator marketing spending in 2023. So perhaps what we really need to do is turn out ‘influencer fatigue’ into action that has meaningful outcomes.

We can demand greater transparency and accountability from content creators, but the reality is that influencers won’t save us. What we need is a rejection of a system which pursues growth at all costs, causing human exploitation and environmental destruction. On an individual level, it requires a shift in mindset where we don’t see our happiness as inextricably tied to accumulating more stuff; where we realise that no matter what new, shiny product emerges – we don’t need it.