This story originally appeared in i-D’s The New Wave Issue, no. 373, Fall/Winter 2023. Order your copy here.

Conversations about haute couture usually happen in Paris, where it perches at the fashion pyramid’s zenith as a near-sacred institution afforded to only a handful of fashion houses. It is defined by rules decreed by French government-controlled appellation: that a garment must be made to order by hand (in Paris, of course) and that it must be fitted on a client in person at least once. While labelled as such, anything that falls short of such regimental one-of-a-kind ‘high dressmaking’ is presumably punishable by the guillotine. Something about it feels incredibly camp.

This is probably why there are always rumours about the precarious fate of couture. Its future has been debated and doubted time and again as far back as when Cristóbal Balenciaga wilfully shuttered his couture house in 1968 as he felt there was “no one left to dress”. Around the same time, a young Brigitte Bardot proclaimed that haute couture “was for the grannies” and Yves Saint Laurent made the switch to ready-to-wear. As long ago as 1965, The New York Times noted that “every ten years the doctors assemble at the bedside of French haute couture and announce that death is imminent.” And yet, it has managed to survive the First World War, Spanish Influenza, the Great Depression, the globalisation of fashion, mass-market machination, the crash of Lehman Brothers, even COVID-19 — and continues to enthral audiences worldwide.

Couture, for industry insiders and outsiders, clearly still maintains a magical allure. Fashion executives see it as halo marketing for beauty products and small leather goods; designers see it as a no-holds-barred laboratory for experimentation and creative freedom; stylists see it as red carpet fodder; the uber-wealthy see it as the ultimate sartorial investment. Fashion writers like myself use it to illustrate fashion’s ever-evolving see saw of commercialism and creativity, traditional techniques and fantastical design, as well as the strange paradoxes of exclusivity and inclusivity, wealth and taste, muted luxury and outré conceptualism.

For Demna, the creative director of Balenciaga who has chosen to go by a mononym since 2021, it represented an opportunity “to communicate to the outside world, and to the industry, who I am as a designer,” he told me in 2021, the year he restored the house’s couture salons at 10 Avenue George V, replete with a decor that gave the impression of a half-century of neglect rather than months of painstaking restoration (which, of course, was the case). The salons set the tone for Balenciaga’s first couture collection in more than half a century. “It’s not about fashion; I love clothes,” Demna continued. “I realised that the purpose of fashion is not about the whole frenzy, the white noise, and the whole digital mayhem we’re living through — clothes are the essence of it, my passion, and couture is the best platform for that. Not sneakers and hoodies, which I love doing, and everybody knows that — this is actually what really turns me on.”

Three years later, I arrived in Geneva, Switzerland on a rainy July morning in search of the designer, armed with a list of questions about his third couture collection shown in Paris a few weeks prior. Far from the grand salons of the show, I find myself on a busy thoroughfare leading to the city’s central train station, searching for signs for Balenciaga between the fast food chains and commuter coffee shops. When a glass-eyed girl in a spoof ‘Top Model’ T-shirt appears, her Balenciaga outfit instantly sets her apart from the sea of navy suits. Surprisingly, she led me into one of the vast corporate buildings lining the street.

The creative nucleus of Balenciaga is, in fact, a co-working space. There is a vast open-plan reception area, booths, breakout hubs: an eerily corporate atmosphere that feels fitting for the various tech and finance start-ups that share the space. On a mock wood wall, giant signage explains: ‘THIS IS WHERE THE MAGIC HAPPENS’.

“Ready-to-wear is like driving on the highway at maximum speed and couture is like walking through the forest picking flowers.”

“I live 30 minutes away, surrounded by waterfalls and nature,” Demna almost apologises when we meet. He is dressed in camo cargo pants, flip flops and a T-shirt with ‘Balenciaga’ spelled out in masking tape. We are now upstairs, on a separate floor, at Balenciaga’s actual offices. Here, the carpets bear the house’s trademark kitsch florals — the kind that you might find at a market stall, but also on silk plissé dresses in Balenciaga boutiques — and Demna sits cross-legged on a beaten-up leather sofa at the end of a long room. The rest of the room is almost empty, beside a table surrounded by orthopaedic office chairs, and a coffee table presenting Balenciaga-branded espresso cups. The windows look out onto another glass-and-steel office, one of which hosts a McDonald’s on the ground floor.

“It’s a very laid-back lifestyle, a different speed—the further you go into the country, the further away fashion becomes,” he reflects. Earlier this year, the Georgian designer relocated his creative team and his family—his mother, his husband Loïk Gomez (aka BFRND) and their two chihuahuas, Cookie and Chiquita—from Zurich to Geneva, although technically they now live closer to Lausanne. “I couldn’t get used to the Germanic aspect of Zurich—too clean and organised,” he shrugs. “Geneva has that little bit of French je ne sais quoi.”

Although he and his team often travel to Paris, home to Balenciaga’s main HQ, he spends his weekends paddleboarding and hiking, far from the world’s fashion capital. He stays connected via incognito Instagram accounts, which he says is to keep abreast of mostly non-fashion content. His self-imposed exile resonates with his recent denouncing of celebrity culture and fashion-as-entertainment, following a global scandal surrounding a pair of botched Balenciaga ad campaigns that, in December last year, led to a conspiratorial barrage of accusations, including that it had sexualised children and condoned child abuse. Country life offered much needed refuge, although he doesn’t shy away from admitting, with a self effacing eyeroll, that “after one week, I’m like: ‘Fuck this.’”

Haute couture has also offered a sense of escapism for the designer. As the world re-emerged post-pandemic, he began to consider a natural extension of his meditative retreat. “Ready-to-wear is like driving on the highway at maximum speed and couture is like walking through the forest picking flowers,” he explains, “With ready-to-wear, I have to review 30 prototypes in one hour, and there’s so much product being made. With couture, you can really focus, and I think you can just be a better designer.” Obviously, he prefers the latter.

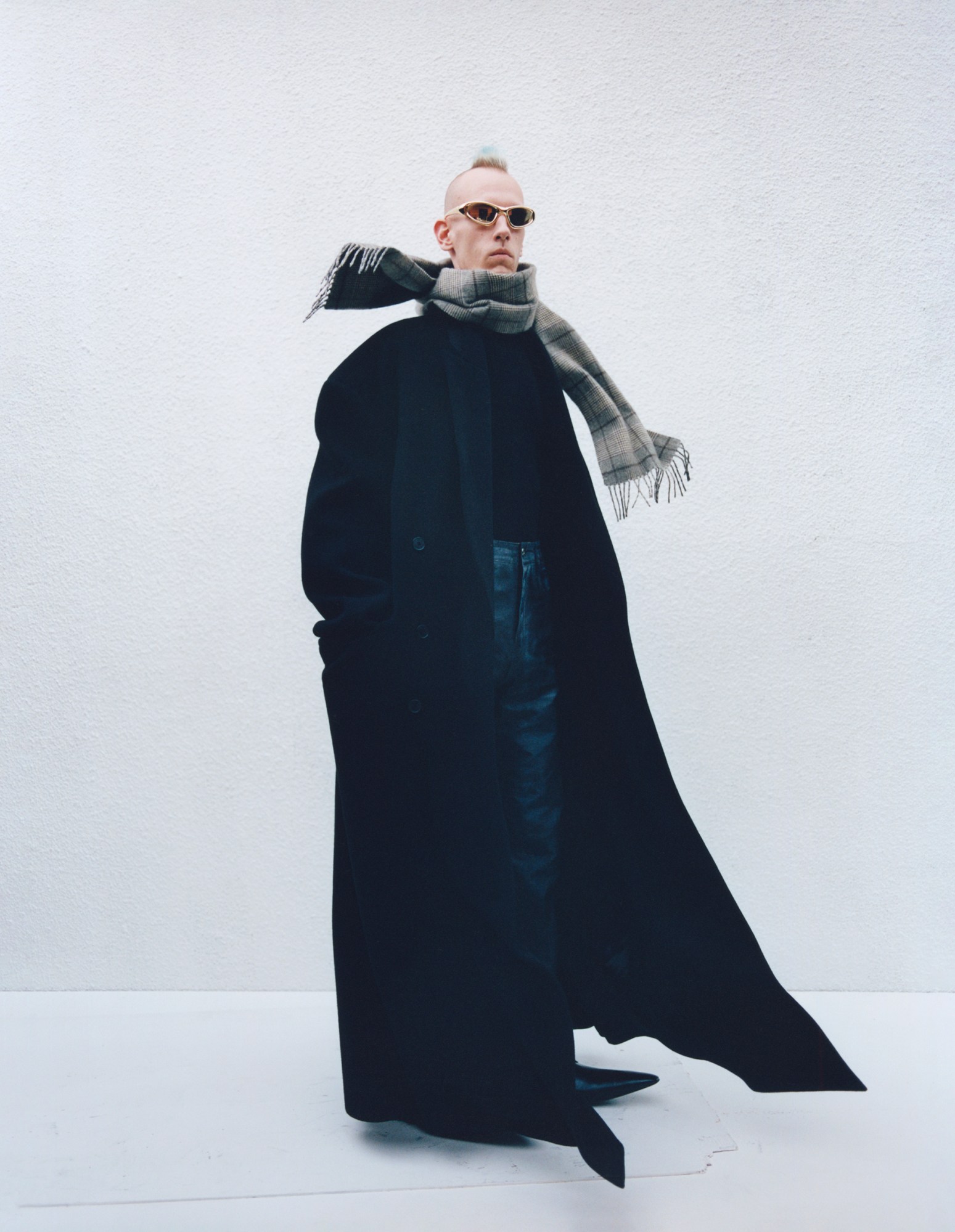

It is also where he can experiment, with both time and money funnelled into one-of-a-kind clothes crafted using mind-blowing techniques. His latest couture collection continued exploring some of his perennial themes — razor-sharp nods to Cristóbal Balenciaga’s jutting volumes, floorsweeping gowns quivering with feathers, trompe l’oeil jeans a result of hand-painting, as well as windswept clothing moulded as if to defy gravity and archetypal black- tie and casual garments reimagined in dramatic volumes and elaborate textures. The first look — a replica of a black velvet gown made by Cristóbal Balenciaga himself in 1966, worn by its original model, the elegant 85-year-old Danielle Slavik — firmly established the bridge between then and now; the last — a CAD-designed, 3D-printed gown of armour made with maquettes used for aeronautical engineering, worn by Demna’s own version of a house model, Eliza Douglas — translated Cristóbal’s sculptural forms that stood away from the body into video-game territory, a space the house previously explored during lockdown with its own game, Afterworld: The Age of Tomorrow. “Making clothes is my armour,” Demna said after the show. “Cristóbal used to say his métier was his armour — and [clothes] are the place where I reconnect with myself.” “How do you make couture modern?” one journalist asked, to which he replied: “You just saw.”

But really, the answer is more complex than the surface belies. “We have a tendency, especially working in this business, to always want to modernise things,” he reflects back in Geneva. “Does it need modernising? If art could exist in the context of fashion, I think it would be couture. Today, lots of questions are being asked: ‘What is fashion? What is luxury? Do we even need creatives at all? There is AI, there is celebrity. Do we really need people who have a vision?’ And I think couture is a great platform to carry that flame of what dressmaking is and how it can survive through these turbulent, value-deprived times we’re living in.”

The concept of couture, he explains, is innately modern because it is an antidote to mass-produced clothes and insatiable consumption. But where he has found space for innovation is in the inner workings of how the clothes are made because, as he points out, couture is “an elitist, old white grandma thing”. His couture team, by contrast, are mostly under 35 — young compared to other houses, many of which often release videos of matronly petites mains hand-sewing garments as a way of showing that couture is handmade by highly-skilled European experts. “What’s going to happen in 20 years? Who will know those techniques? People who work for 20 or 30 years at other houses will retire.” When assembling his team, he promoted from inside his ready-to-wear studio, as well as scouting promising young talent. “It wasn’t super important that they had years of experience,” he points out, “because someone with decades of experience of embroidering feathers might not understand what we’re trying to achieve.”

If Cristóbal Balenciaga was famously a perfectionist, a devout Catholic who sought sacred apotheosis in the seams of barrel-shaped suits and statuesque gowns, then Demna is a designer who convinced his audience that ostensibly ordinary items can be perfect, too. “Perfection is fucking torture,” he declares. “I take a lot of time destroying things, making them perfect-er than they were before. You can never get there. It’s great, because it makes you move further, trying more and more, but you’re always frustrated because the harder you try and the more you change, you can destroy what was originally a good idea.”

Whereas Cristóbal famously included one dress made entirely with his own hands in every collection, usually in his signature Spanish black, Demna is more open-minded about the possibilities of technology and the mechanisation of dressmaking (his AW23 ready-to-wear collection, for instance, features a puffer jacket designed by artificial intelligence). “You cannot be an ostrich,” he smiles. “I’m more like a meerkat—I need to see what’s out there.” In his couture collections, he has introduced digitally aided techniques alongside traditional savoir-faire: 3D printed garments, technical neoprene fabrics developed in Japan, soundtracks made with AI, traditional silks and satins shot with aluminium to create crinkled couture- like volumes. “I think there are technologies today that, if they had 50 years ago, they would have used,” he asserts. “Why just blindly follow the rule book, when we can also add some new rules to it?”

“It took me a while to understand that fashion is one of the most conservative systems in the world,” he adds. “You look at the food industry and it is so innovative, so open-minded. There’s so much going on in pharma, but fashion—well, we like the stitches on the leather bag the way we liked them 100 years ago.”

Who is carrying the bag is equally important to Demna. Casting has always been paramount to Balenciaga’s shows, as far back as the 40s, when Cristóbal established a new way of presenting his clothes. He took the true measure of a woman’s body and created clothes that had a positively transformative power, turning even his predominantly middle-aged clientele into what were then described as elegant “monsters”. He preferred models with the physique of the women in his Basque hometown, San Sebastián. “M. Balenciaga likes a little stomach,” one of his vendeuses famously observed. They were also often middle-aged (like his clients) and not traditionally pretty. He personally instructed them never to make eye contact, pirouette or smile.

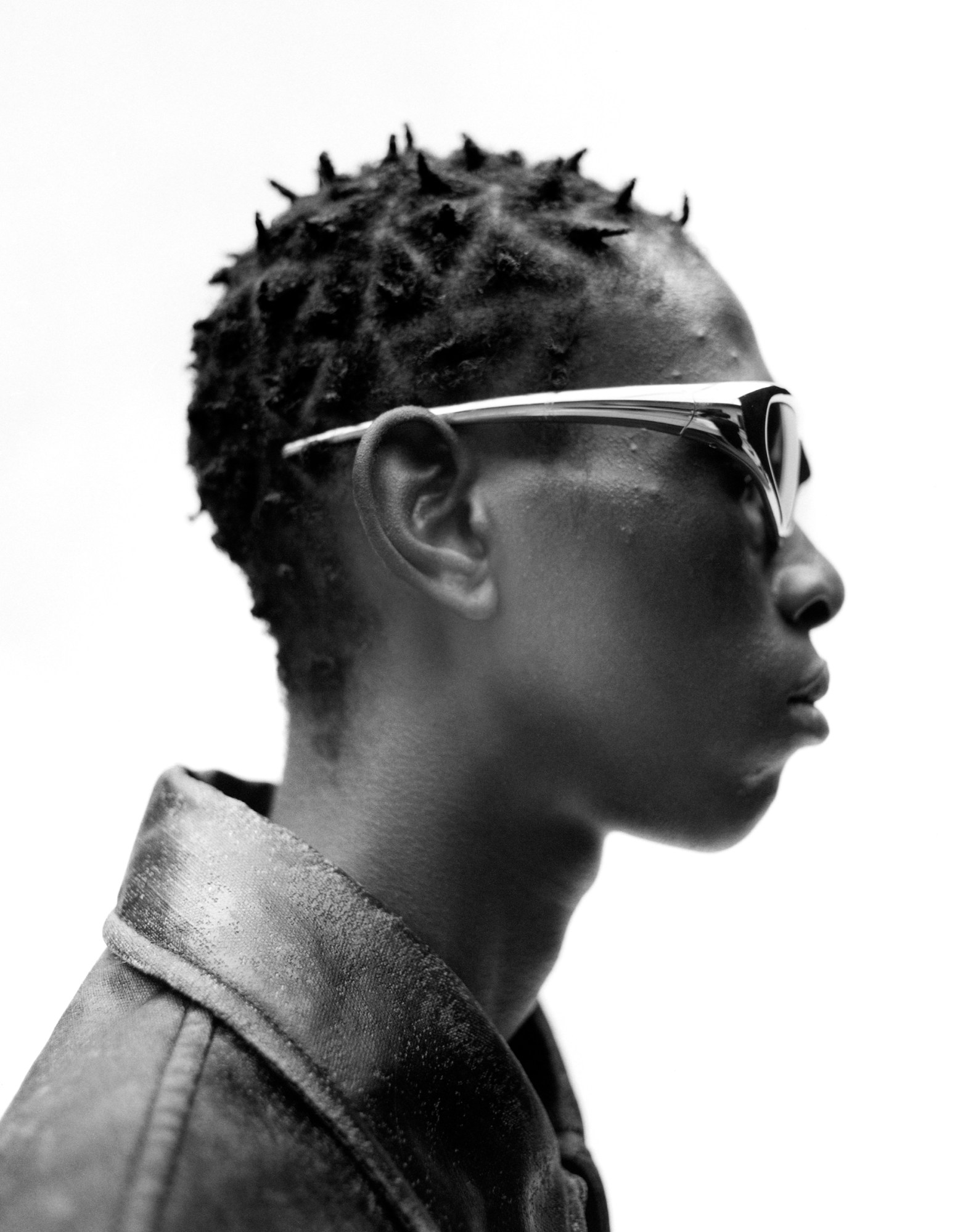

Demna’s models, too, are key to his aesthetic, and have little to do with notions of luxury or conventional beauty. But they’re also part of his unofficial cabine, since some of them—like Eliza Douglas and Minttu Vesala, both artists—are in every show, hauntingly bare-faced in their floorsweeping gowns. There are men, too. His couture collections are evenly co-ed — not that it matters, he says, because Balenciaga’s 30-or-so paying couture clients order whatever they want. Half of them, he points out, are men. “When I tried wearing my mum’s heels as a little boy, I was strictly punished, because this was not acceptable for a boy in [the] culture and society in which I grew up,” he told a journalist last year. “Putting men in high heels for couture was a symbolic act of liberation from those absurd boundaries for me.”

Cristóbal once told a friend, “I regret not being younger, because then I could create the amusing but tasteful ready -to-wear the times we live in demand — for me, it’s too late.” The opposite applies to Demna, who says that he desperately wants a break from producing the buzzy ready-to-wear collections and viral accessories that he has been known for since starting his label Vetements in 2014, originally an anonymous collective of friends, soon known the world over for its spliced-together jeans, lighter-heeled boots, DHL T-shirts and giant hoodies. At the time, they were divisively derided as Emperor’s New Clothes, but the aftershock was unstoppable, ushering in a post-Soviet, post-internet aesthetic to high fashion (Demna was born in Georgia in 1981, living through civil war and eventually becoming a refugee in 1993). His unique perspective upended traditional ideas of branding and connotations of banality, which makes a lot of sense considering Demna once told a magazine: “I remember seeing a Coke can for the first time and thinking it was a nuclear bomb”.

Since his appointment at Balenciaga in 2015, Demna has transformed the house from a 350 million dollar business into a two billion dollar megabrand, constantly making headlines with his memetic designs, like stiletto-heeled Crocs, Italian-crafted Ikea bags, souvenir- shop Eiffel Tower trinkets and the pseudo-political ‘Bern-lenciaga’ merch.

In doing so, he completely shifted the psychology of fashion, giving value to ostensibly ordinary clothes that we may already have in our wardrobes or find in second-hand stores, and therefore dismantle fashion’s cashmere- clad elitism. At Balenciaga, he has taken the populist totems of how people really dress and pedestalled them as holy grails of desire. The world laughed at first, but soon, the lobbies of five-star hotels and airport lounges around the world were filled with his sweatshirts, comically oversized sneakers and trinket-laden bags. His most loyal customers loved the so-called ugliness of it, both Berghain club kids as well as household names like Nicole Kidman, Justin Bieber and Kim Kardashian.

“Fashion can be too uptight,” he laughs. “I think it’s important that there is a fun element to it, but very often people felt like we were making fun of them, and they took things personally, almost like, ‘How dare you? I already have a garbage bag.’” Beyond following in a Duchampian tradition — with nods to one of his heroes Martin Margiela — there is, he says, simply a direct visual appeal as well as an intellectual subversion. “I think it’s often a ‘why not?’ moment. A bag of chips as a handbag is fucking funny. I think what has become perceived as provocative is the context, because Balenciaga has always been seen as a luxury brand — and a luxury brand for most people equals beige, grainy leather. For me, Balenciaga is everything but that.”

Humour aside, for him, clothes are thin-slicing cyphers for understanding someone and how they navigate the world. A month after we spoke, backstage at his SS24 show in Paris, he began to explain how during his summer vacation in the South of France, he had “a very horrible experience” where well-heeled holiday dwellers around them moved away from him and his husband because of the way they were dressed. The next day, the couple ventured to the local ‘resortwear’ boutiques and bought chino shorts, linen shirts and loafers. “It was an anthropological project to experience how it is to fit in for once, and how it is to be the kind of Demna that the world can tolerate,” he explained. “It felt disgusting, and it confirmed to me that the only way I want to be, and I want my work to be, is loyal to myself. I won’t try to be someone or something else — because I will never fit in.”

Indeed, between the playful irreverence of crisp packets and the serious self-expression of identity at Balenciaga is a grey area which can easily be misconstrued. Following the outrage surrounding its controversial campaigns, during which Balenciaga was ‘cancelled’ and Demna was given full-time protection due to death threats, stages of hyper-vigilance and sensitivity checks were implemented in the creative process at the house, across all product design and imagery. It introduced a tightrope between cultural awareness and instinctual creativity, radical ideas and sensitivity, and of course, countercultural subversion and mainstream acceptance.

The wake of the experience also offered a moment for Demna to reflect on the extraordinary settings for his most memorable shows—a flooded theatre, a giant mud pit, a blizzarding wind rotunda, a red-carpet premiere to a specially-commissioned Simpsons screening—and whether it was all just too much. “I’ve had such a crazy journey in which I grew [Balenciaga], and it became very loud,” he quietly reflects. “The whole idea of this crazy elaborate spectacle show—people just spoke about that. Nobody spoke about my collection, because they couldn’t see much of it—even though they were loaded with a lot of really good product. I felt frustrated, I almost felt like I betrayed something of my own, making it more important than the actual work and the ideas that I produced with my teams.” After his SS23 mud show, he told a journalist that he “felt like shit”.

These days, “it’s balance-iaga,” Demna laughs as we discuss the constraints. “I think the role of a designer is to be aware—just as we must be aware of what we eat, of what we wear, of the sensibility of the world around us and how things can be misinterpreted and hurt people. It’s a part of human nature to grow stronger when you are hurt… but that awareness cannot guide your creativity.” It’s an essential system in place for a brand the scale of Balenciaga, he adds, even if it’s “kind of like a turn-off.”

Such are the demands of a creative director at the helm of a multi-billion dollar megabrand. You can understand why, for him, haute couture became a meditative temple and a refuge from the noise elsewhere. “I feel like luxury has held fashion hostage,” he asserts. “The main element of the fashion system is growth, and luxury wants to be very loud to sell more small leather goods. It’s like the elephant in the room because everybody knows that. Fashion is different though; it needs to be small to be good.”

What could be smaller than haute couture? For Demna, it is the ultimate crystallisation of his job as a dressmaker — he is convinced that, in another life, he was a humble seamstress. “I can’t do anything else, to be honest, it’s my raison d’être,” he confirms. Besides, there’s still more that he would like to achieve. “We have a lot of areas that we haven’t even touched on.” His ultimate ambition is to create “a product that doesn’t need to be bought”. It may sound like another of his paradoxical provocations, designed to ignite conversation – but little does he realise that he already did. Such is the power of haute couture — clothes for the few, a sight to behold for the many.

Credits

Photography Stef Mitchell

Fashion Sydney Rose Thomas

Hair Akemi Kishida at MA+

Make-up Karin Westerlund at Streeters

Set Design Anne Aubert

Photography Assistance Daniel Johnson, Pierre Senechal, Jakob Muller Meernach and Anton Grebentsov

Fashion Assistance Marianne Chateauneuf and Mathias Rota

Hair Assistance Brenda Irène Ohale and Karla Garza

Make-up Assistance Morgane Nicole

Production Kitten

Casting Gabrielle Lawrence at People-File

Models Anne Kroon at Known, Sweia Hartmann, Mami Akol and Ash Rouault at Select, Deborah Akanni at Oui, Mortiz Wöhlbier, Seng Khan at Women, Kamil Sznajder at Aquamarine, Piotr Szatan at The Squad, Guo Jike at RockMen, Maguatte Thiam at Studio, Amance Bastard, Arthur Del Beato at Milk, Quadri Olajuwon at Xdirectn and Anton Grebentsov

All clothing and accessories BALENCIAGA COUTURE