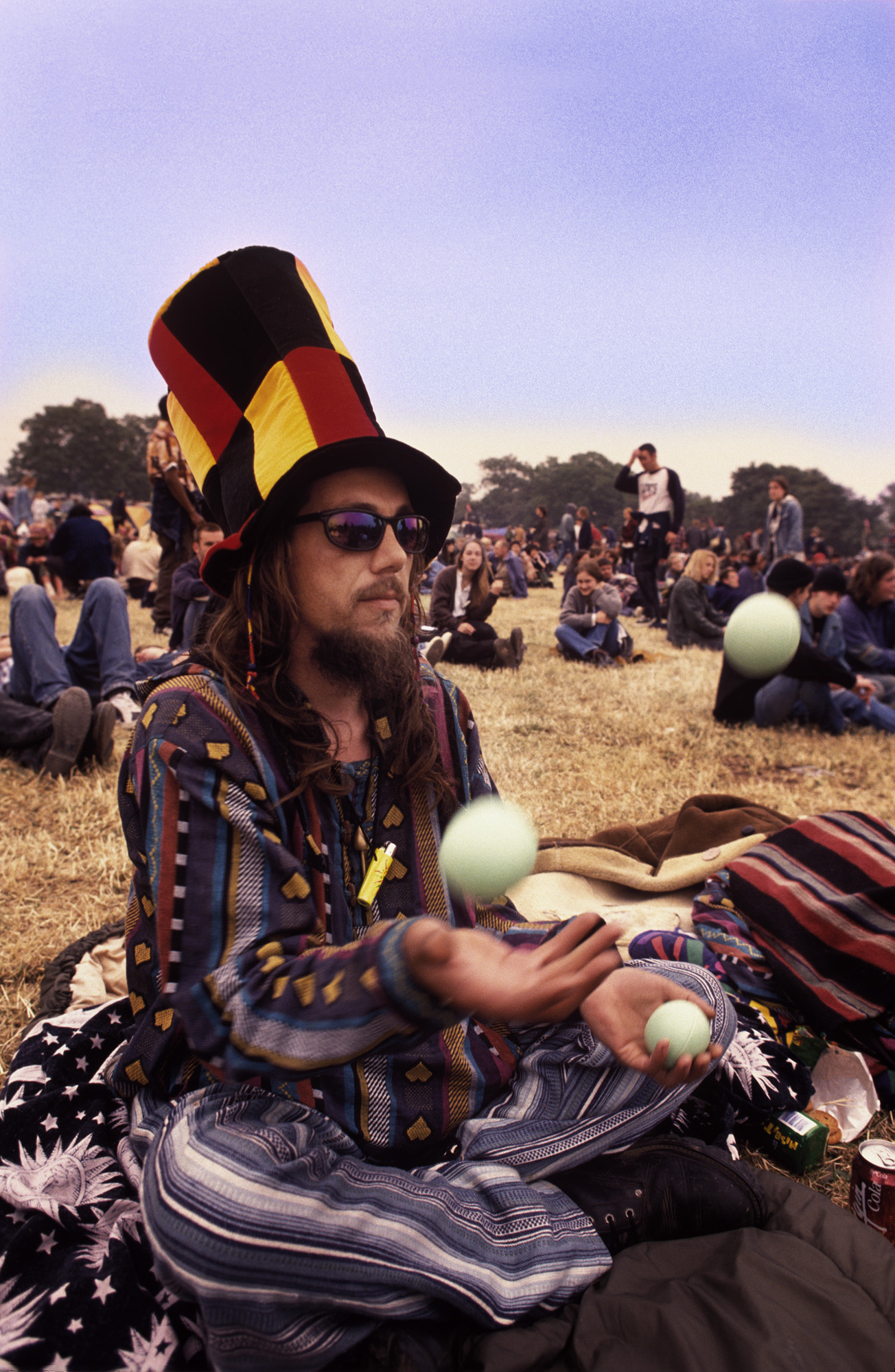

Derek Ridgers, the master documenter of all things subculture and underground, spent a decade shooting Glastonbury on assignment for NME in the 90s. We thought, given all this, it might be nice to share some of these classic shots in tribute. Taken at a very different moment in Glastonbury history — one far removed from its current capacity at 79 stages and 200,000 attendees — these images are a reminder of the humble, counterculture origins of Michael Eavis’ world renowned festival. “I enjoyed every single moment of the time I spent shooting Glastonbury,” Derek says. “2000 was my last time — the one Bowie played at. But if I could still get the right passes, I’d still go.”

Here, Derek selects a handful of his favourite Glastonbury shots from his extensive archive, as we discuss with him what the festival was like, pre-gentrification.

Tell us a little bit about your work shooting Glastonbury in the 90s. What was it like back then?

I was always there on assignment for NME and, to begin with, it was great. The backstage car pass meant one could usually find a great spot only a few yards away from the backstage bar — where all the journalists and quite a few of the bands would hang out. In later years the backstage car parking was moved further and further away from the action and it became much more of a schlep. I’d usually drive down at the crack of dawn on the Friday. There were always stories on TV of long traffic jams ,but I never seemed to find any. I’d shoot all day Friday, sleep as best I could in my car and shoot all day Saturday too.

Then, in the early hours of Sunday, I’d drive back to London, usually going straight to an all-night film lab to get my colour film processed. I’d then drive home to process and print a selection of black-and-whites and deliver everything to NME as soon as it was all done on the Sunday morning. Then, obviously with no proper sleep for 48 hours, I’d drive back and catch the later acts on Sunday evening. It was very hard work but I loved the intensity of it. I’d have been ready to do it all again on the Tuesday, if I could have done.

Were many people other photographers shooting for big publications when you were there?

Yes, even 30 years ago Glastonbury was quite a big deal and they didn’t give backstage or VIP passes to just anyone. Plus, there were a few well known but highly illegitimate tricks to help with the aforementioned. But working for the NME, one would usually find a way to get a seat at the top table.

Did you enjoy it in and of itself, or was it just about the photography?

I don’t suppose I’d have ever been there without a camera. But, saying that, if I didn’t have a camera, I’d probably never leave my couch. The camera gives my whole life a legitimacy that might be in doubt, if I didn’t have one. And it’s allowed me to extend my adolescence well into old age.

Given how expensive and commercial it’s become, back in the 90s did it feel like you were shooting something a little more authentic?

To begin with, it was probably more of a counterculture thing than anything else. The fact that ‘the man’ wasn’t controlling everything and charging people through the nose for it, was all part of the attraction. I’ve been going to open air music events since the 60s and, to begin with, they were mostly free events. But even then, the appeal of popular music wasn’t the universal thing it is these days. When Pink Floyd played their first free show in Hyde Park in 1968, you could pretty much rock up at any time that afternoon and still get a great view. I know, I did. I was one of about 30,000. Nowadays if Pink Floyd re-formed and played a free show in Hyde Park, half the world would want to be there.

As someone with a keen eye for different style tribes, what kind of intersection of subcultures could be found at Glastonbury during the 90s?

To begin with it was really just a hippie thing. By the time I started going to Glastonbury there were still quite a few flower children, travellers and assorted members of the counterculture. Like everything else, it gradually changed and became more and more corporate. It became gentrified. These days you can rent a luxury yurt. If you have a spare £13K kicking around.

Did you ever cross paths with familiar faces from the clubs and parties in London you shot?

Occasionally, yes, but a lot of the night creatures from the London clubs don’t come out much during daylight hours. And they’d either melt in the sun or all their warpaint would wash off in the rain. Many of them wouldn’t be seen dead at something quite as uncouth as a pop festival anyway.

Limited editions of Derek Ridgers iconic music portraits are available at Sonic Editions.

This story has been updated.

Credits

All images courtesy Derek Ridgers