It is a very sunny afternoon in June at the Sarabande Foundation in Dalston and Bianca Saunders is giving me a tour of her studio. Her assistants are hard at work on her SS22 collection. Patterns are strewn across her desk. Pinned on the wall are some images of bodybuilders she’s been looking at for inspiration for the season ahead. “I’m obsessed with the way the clothes move around their muscles,” she says, pointing to their mountainous biceps. “The way their muscles change the pattern of the clothes themselves.”

This fascination is indicative of Bianca’s approach to fashion. She mixes together playfulness and curiosity with rigorous formal exploration and technical excellence. There’s an assured and slightly restless creativity that runs through everything she does. “I get bored easily,” she says. “Or maybe, more correctly, I enjoy doing everything. I like to do all these different things in the studio – cutting patterns, doing the research, designing. Fashion was always my light. I know it sounds cringe but it was always what I wanted to do when I was younger.”

Bianca grew up in Lewisham. She still lives there. Her mum is a hairdresser, her dad a plasterer, and she credits both with encouraging her to do what makes her happy and fostering her creativity. She went to Kingston to do a BA and then the Royal College of Art for her MA, and started properly designing and thinking about menswear there. She then launched her brand, under her own name, as soon as she was done with school “because it was the easiest way to have a job that didn’t feel like having a job.”

She is one of those rare designers who seems to spring to life both aesthetically and conceptually fully formed. From the very beginning you could sense how talented she was. There was already a world around these clothes, and characters who inhabited that world. Just look at her first two collections – her AW18 graduate collection and SS19 London Fashion Week debut – and you can see that almost everything she was preparing to say about masculinity, race and fashion was already there being sketched out.

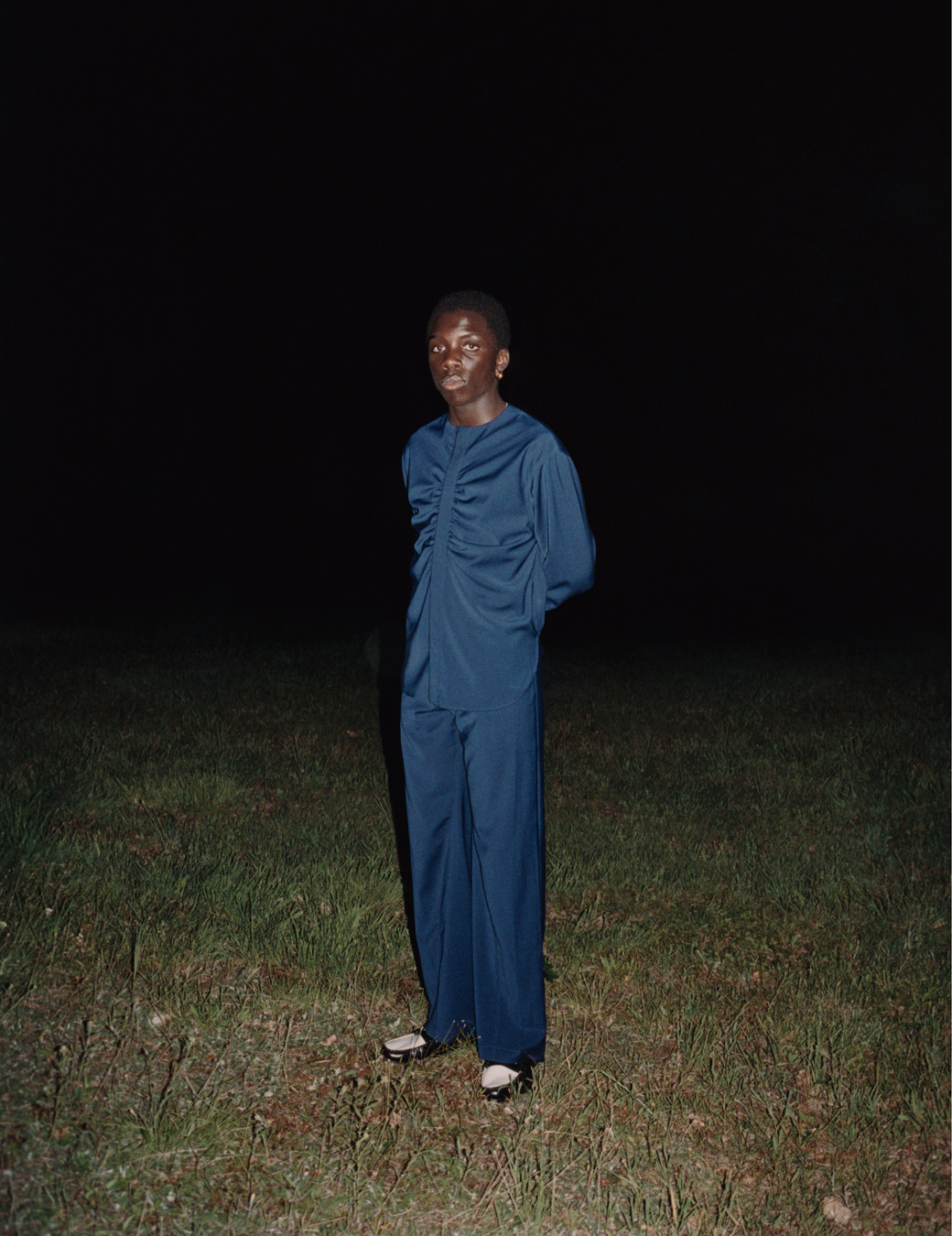

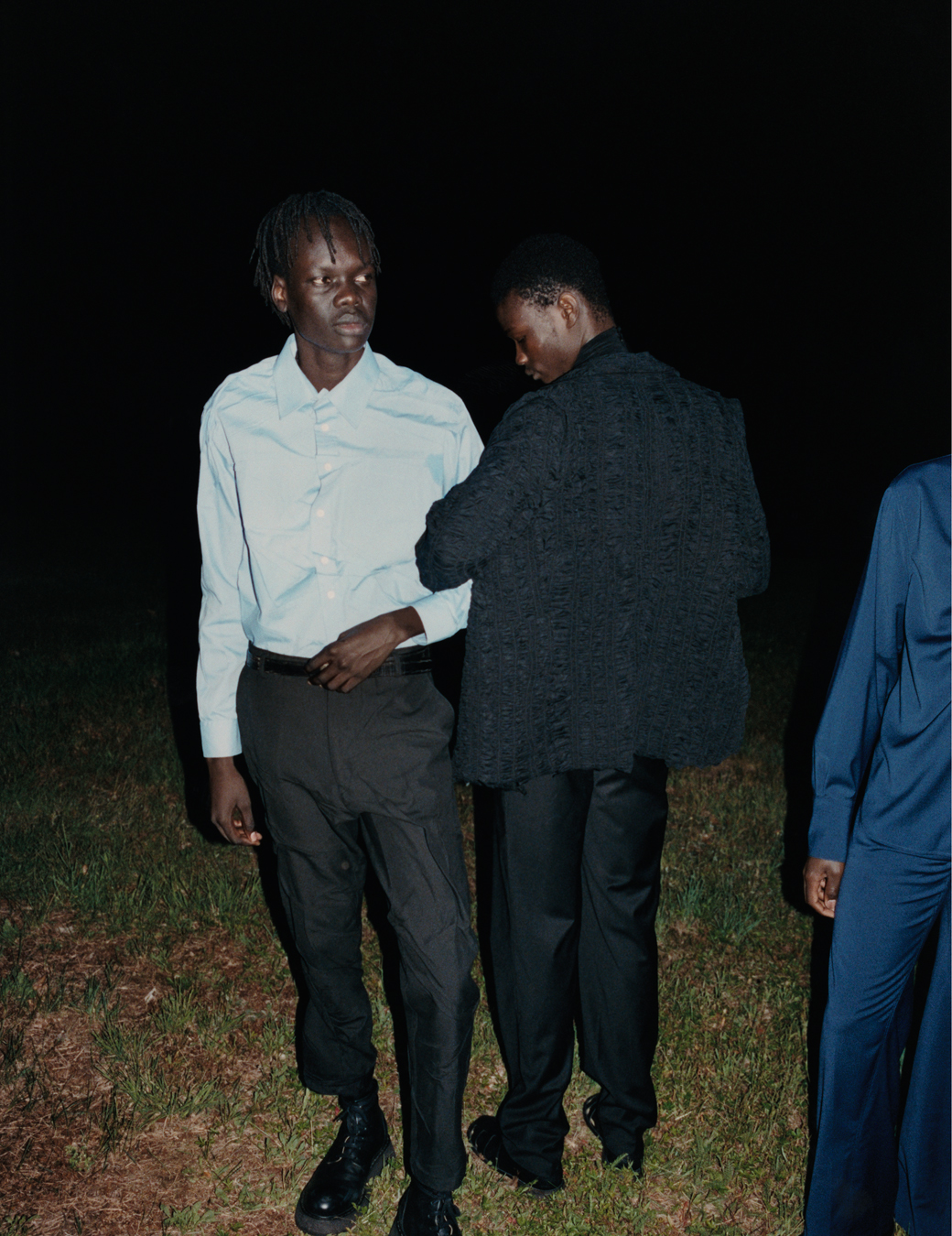

Take SS19, for example. Shirts are cinched in at the waist, or cut a little too high; they are ruched and asymmetrical. Trousers are slit up the front and twisted a little. Her silhouettes look like they were cut on the body to mimic the way clothes are actually worn. This all comes from careful, curious, studied observation. Her clothes are confident, clear, beautiful, with an elegance and strength and pride in themselves. They seem to propose new ways of seeing masculinity, or offer new possibilities and ways of holding yourself as a man, or even how you, as a man, could be wearing clothes that don’t fit into the rigidity of hegemonic masculinity. It’s not just about softness, or the blurring of binary dressing, but more about an all-encompassing attitude, a stance, a pose.

When she was studying at the RCA and Kingston, London’s menswear scene was easily the most exciting and forward thinking of the big fashion cities. Bianca was moulded by that scene and drew inspiration from designers like Jonathan Anderson and Craig Green. She cites both as influences, although you can feel their influence more than you can directly see it. Aesthetically they are not similar, but it is in the way she approaches gendered dressing with a freedom, and the way she turns to the foundational garments of menswear and finds new ways of seeing them and new ways of wearing them; it’s there in the mixture of the formal intricacies of tailoring with the attitude of streetwear.

“There were some really weird patterns we used at the beginning,” she explains of her process and how it has developed. “And there were some mistakes too, but the mistakes led to some interesting discoveries. We adapted when things were slightly off in the fittings or we altered the seams directly around the body. A lot of it comes from experimentation, from making things I might hate at first or from revisiting things later on and trying to see them in a different light. Like this jacket,” she says, pointing at an image from her AW21 collection. “This is a new version of an old jacket we’d made, and we took the padding out, took the quilting out, allowed it to move a bit and feel different. Or these trousers,” she says, pointing to those aforementioned trousers with the slit up the middle seam. “I keep trying to get rid of them from the collections but people love them.”

Movement is one thing at the heart of what she does. Her clothes look like they are caught in action or encouraging it. They have an awkward grace to them, contorted and wriggling. You want to work out how they are made, their angles lure you in. A lot of this comes from observation of how men wear clothes, or carry themselves when wearing clothes, how they edit the clothes themselves or how their bodies do. Two things indicative of this influence of movement and observation, that Bianca was looking at recently, were the works of Hans Eijkelboom and Erwin Wurm. With Hans Eijkelboom it was his work An Ideal Man that she looked to, a photographic series in which the artist interviewed women about their ideal boyfriends, and then he turned himself into them – using clothing and make-up – in a retooling of the female/male gaze. In Erwin Wurm’s One Minute Sculptures, participants followed his instructions and created sculptures out of their bodies and everyday objects, like clothing, fruit and furniture. “I wanted it to feel a little surreal,” she says, of how these influences have found their way into her work. “I wanted to twist things that felt familiar to people, to play with ideas of tactility.”

In a project for GucciFest, initiated and designed during the early days of the pandemic and lockdown, this mode of observation was carried through into the display of the clothes in a short fashion film called The Pedestrian, made with BAFTA-nominated filmmaker Akinola Davies. The film featured the models, usually so unknowably silent, joking and talking, describing themselves, their ideal dates, their ideal partners. It was a playful and sweet and tender vision of masculinity and romance. “It was really fun doing the auditions for it,” she says, “And the show where the models were dancing, too,” she says, in reference to her AW20 show. “I’m really interested in breaking this fourth wall that exists in fashion. I think you have to creat new ways of showing and presenting. I don’t think what I’ll do next will be a classic runway show, it might feel a bit anticlimactic.”

It’s been a busy lockdown for Bianca in other respects too. She’s currently working on a few collaborations, expanding her line’s offering of accessories – including a bag that’s influenced by the way a large folder or art portfolio crumples and moves when held under the arm, because of its unwieldy size – and has been busy in Paris with prizes and an art exhibition, where she created a sculpture with wires and garments.

This year, she made the final of the LVMH Prize again, with the winner to be announced during Paris Fashion Week in September. When I interviewed her, she was preparing to go back to Paris. She’d been nominated for the ANDAM Fashion Award too, one of the most prestigious. She won it a few days later, joining the likes of fellow winners Martin Margiela, Anthony Vaccarello and Christophe Lemaire.

It was a little unexpected maybe, but not undeserved. And despite the growth and accolades, you don’t get the sense that things will change too much. Bianca’s is a project that feels rooted in her self and her interests and her expertise, rather than in anything cynical. She simply remains an incredibly talented designer from Lewisham with a mission to observe and interpret and define the way men dress in the 2020s.

Credits

Photography James Brodribb

Fashion Milton Dixon III

Hair Tomo Jidai at Streeters using Oribe.

Set design Hans Maharawal at The Wall Group.

Styling assistance DeVante Rollins.

Hair assistance Ann Gior. Make-up assistance Ayaka Nihei.

Production Bonnie Osborn at Bonnie Charm Inc.

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING.

Casting assistance Alexandra Antonova.

Models Dwyer at Ricky Michiels, Kyle Dopgima at Next, Duot Ajang at Muse NYC, Michael Martin at DNA, Ali Ba and Benzo Perryman.

All clothing BIANCA SAUNDERS.