Tired of seeing independent designers struggle to build a sustainable career, 1 Granary launched VOID, where young talent is connected to established creative teams. Now at its second edition, the project resulted in an exhibition during London Fashion Week and a series of unique zines, collected in one publication . We spoke to the six VOID designers about their work, the power of collaboration and their hopes for the future.

Sinéad O’Dwyer’s work is always in interesting company. In summer 2017 one of her silicone busts shone confidently in a pink-hued, dreamy spread with the pop icon Bjork at its centre; a year later, one of her looks could be spotted on model and drag queen Aquaria as the four finalists of RuPaul’s Drag Race performed the song America; and most recently, Sinéad was invited by curator Bryony Stone to create the sculptural pieces worn by artist Zoe Marden and dancer Becky Namgauds during a night of slippery, carnal performances forming part of the exhibition all in: bodied. These regular stamps of approval bear witness to an approach that wash over the boundaries of ‘sculpture’, ‘garment’ and ‘performance’, and a vision that resonates with those interested in fluid, queer and changing matters.

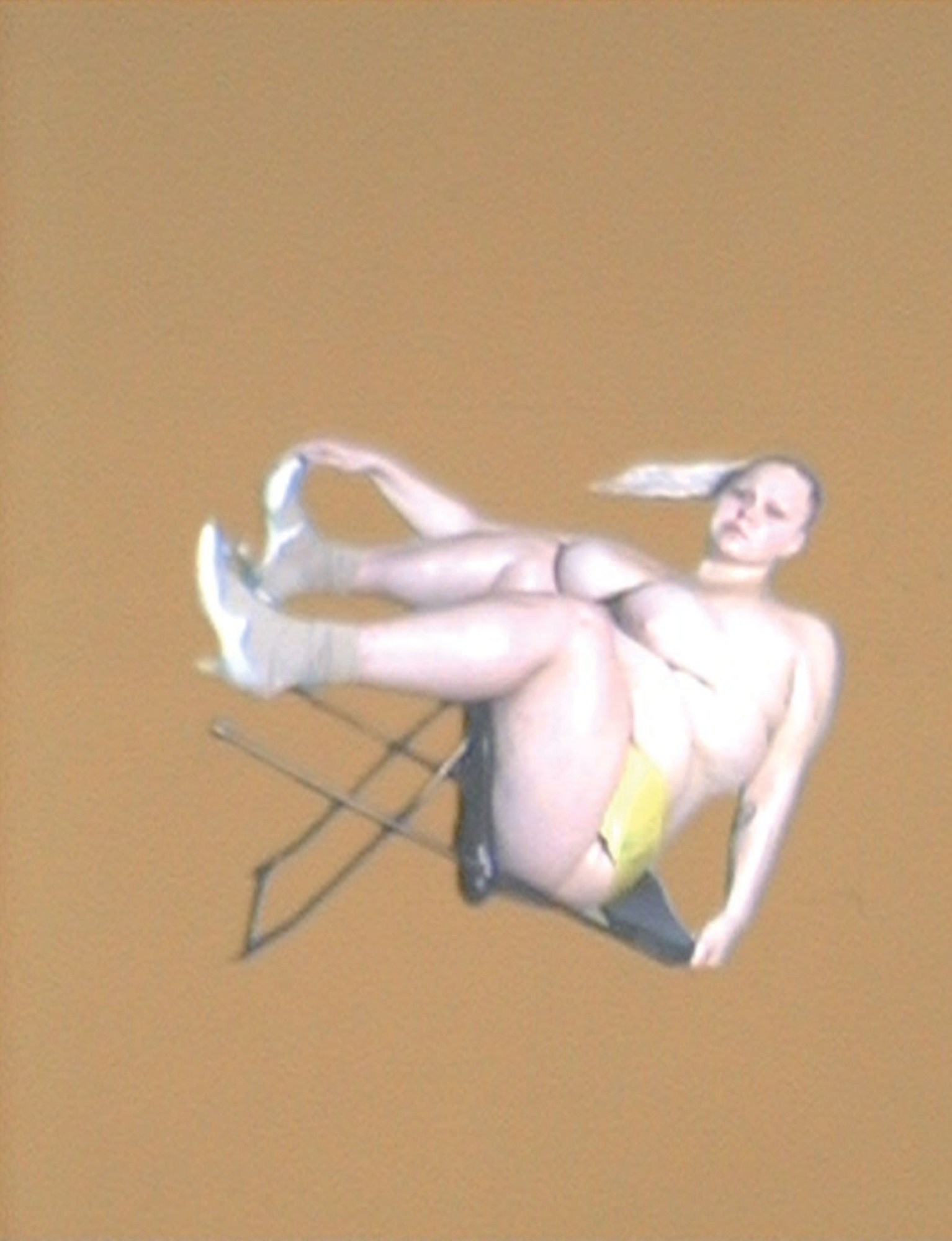

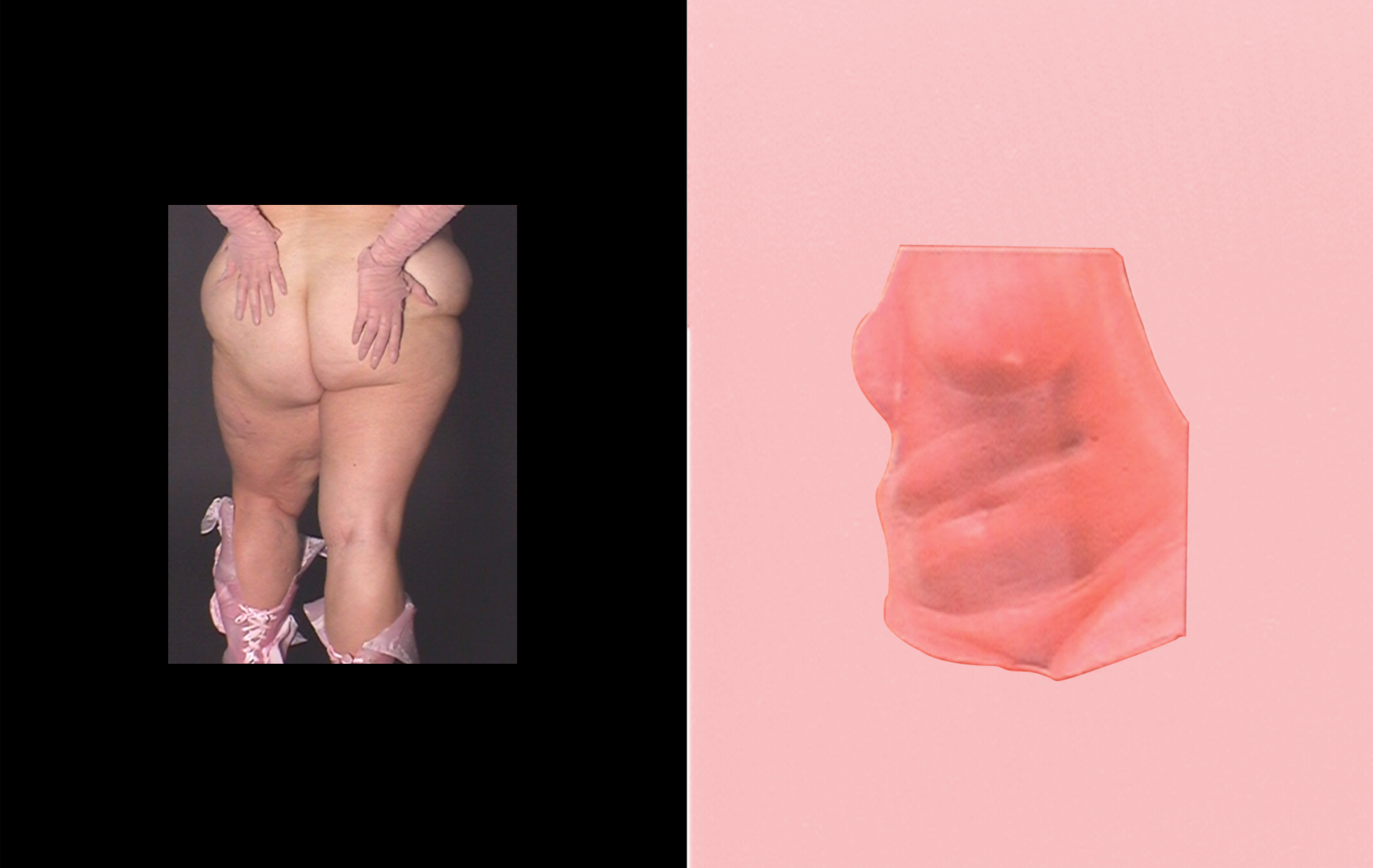

While recognition would seem to bestow easily on the designer who has only just graduated from the Royal College of Art this summer, it is thanks to a complex practice that does not shy away from the intricate and singular — be it shapes, persons or techniques. Sinéad examines the body with the thorough eye of a doctor or lover. Her lens falls on individuals otherwise invisible in fashion: the asymmetrical, curvy, or plus size (in other words: normal, fleshy humans). In her embrace of a diverse group of people, her work is resolutely democratic, but in a way that rises above the pits of the mainstream. With her graduate collection she presented a series of silver-lined body casts of her friend Jade, which sprung from aggrieved conversations about uniform fashion imaginaries, and many, full days of casting, sculpting, and resculpting — difficult pieces, each one a critique of the homogeneity of model bodies, and a sweet antidote to fast and standardised fashion.

For VOID, Sinéad collaborated with artistic director Jasmine Raznahan, stylist Danielle Emerson and photographer Sharna Osborne (“who I always wanted to work with” she says). We discuss her work, and how it very often develops from these types of earnest collaborations, below.

Can you explain the role of the female body in your work?

Many designers talk about how the body motivates them without really looking at it — they look at mannequins or fit models. Sometimes it feels inauthentic, as if they only care about one type of body. I wanted to create garments where the body was actually, literally, there, without changing it. When deciding to lifecast a body, my friend Jade felt like a natural fit, because we had been discussing sizeism in fashion, and because she has a beautiful body with so much form. I wanted to work with a body which was almost the opposite to the ones patterns are usually cut for. Beginning to lifecast was the most important step in really observing a physical body and not just saying that I was observing it.

You often work with a muse. Can you talk about the nature of your collaborations, with regards to your muses and in general?

I want there to be authenticity in my practice, by creating actual relationships with the people I work with. My garments are telling the story of individual bodies, as opposed to making universal claims. If you don’t know the person well enough, I think you end up generalising. It could easily become an act of ‘using someone’s body’ if the muse was not also a collaborator, just a model I hired for the day and casted because she had a nice ass. The person has to be a part of the story. Me and Jade travelled to the lifecasting place together — it was the day after her birthday — and after having cast her, we had lunch and talked about this experience we’d shared: all of that was really important to my process. It is also why I did a zine that features interviews with each person I collaborated with. For example, in Jade’s case, to facilitate a dialogue between her and the object I made from her body. The more you talk with one person, the more you understand how complex their body is, and the easier it is to make sure that it does not turn into a stereotype.

Your process is very technical and has required that you learn, among other things, the ins and outs of moulding and casting. Why have you chosen to work with these complex methods?

I love the process, it is the most exciting part. I love experimenting with industrial techniques and really push convention, so much that I sometimes question whether it is going to work or not. You never really know what you are going to get. It is such a long process. I start by lifecasting in alginate and plaster bandage and then I pour hot clay into the cast, which makes a clay version of the piece I want, one that still needs additional sculpting. When I have a clay sculpture I am satisfied with, I decide how to piece the mould together, then make each part using fibreglass. I try to make the fibreglass as thin as possible, and embed garments inside, to create these really interesting compressions and textures. I’ve been thinking a lot about how the process relates to ideas about the body, how the relation between the industrial nature of my technique and the fragility of the actual body is analogous to the way we treat our own body, or how society treats our bodies. It is a paradoxical process made up of extreme harshness and fragility at once.

You also make performances and here too, the position of the body is explored, in relation to eating, rituals and etiquette. What are the ties between your practice as a performer and as a designer?

Many of the conversations I had with my performance partner Jolene made me reflect on how I perceive my body in different contexts and settings. I see it as a real conceptual precursor to my final collection, an interrogation of the skewed perception we have of our body, and a desire to parade different types of bodies. The performances were also about healing. We created spaces for play, where the body could perform outside the bounds of where it is usually allowed, whether for the two of us or for a public audience. I think it has had a huge influence on my most recent collection, but not necessarily a direct one.

For VOID you collaborated with Jasmine Raznahan and Sharna Osborne. You have told me the collaboration with Jazmine and Sharna reintroduced some rawness to your work. Can you elaborate on this?

Yes, the rawness is exactly what was missing from the presentation of my final collection. When presenting it, I really wanted to focus on the garments. It was important to keep it clean. But messiness has always been important to me — as seen in my performances as well. With Jolene, I created these scenarios that were really beautiful and well-constructed, only to let them transform over time or disintegrate completely. We would do things like corner an entire glass table and pour two inches of lard into the form, then get hot pans and put them on top of the lard so it would melt. Something similar is true for my collection, but here it is through Sharna’s work, the styling, the hair and make-up, that a more rough and raw feeling has been introduced. I love it. I was happy with the way my lookbook was shot, but going forward, having someone like Agústa as a model, who is so expressive wearing the pieces, and Shana shooting it, as this strange story of a girl coming to live, adds another layer to my work.

What do you especially hope to learn or gain from participating in VOID?

VOID is so incredible because without it I would never have had an opportunity to work with someone like Jasmine or Sharna, people who have taken the documentation of my work in the right direction. This particular collaboration has helped me develop a brand image, its overall aesthetics and style. Jasmine and Sharna immediately had so many ideas about how to shape the imagery of my work. But VOID is not only that. I can always turn to the people from 1 Granary if I have any questions about the development of my work.

While having just graduated, you have already received a lot of attention, especially for your body casts. What, as you see it, are the biggest challenges for up-and-coming designers in keeping their momentum?

Money. I mean that’s it. If you don’t have some sort of investor or have an amazing freelance job where you magically make a lot of money and which does not require that much work either, it is really hard to find enough time to be in the studio. I think that is a really big challenge, but hopefully, I will figure out how to get paid for things that are more relevant to what I am actually focusing on, so I’ll have enough time to make and the money to make.

Last time we spoke, you told me that you were about to begin the development of new work, partly for the showcase coming up in Paris. How will this differ and align with your previous work?

The collection I showed in June is a starting point and not necessarily products that one could wear or take home that same day. It was very much the beginning of a conversation. What I’m working on now is the development of those ideas into things that are a bit easier to wear, actually, I wouldn’t say easier to wear, because they are not more commercial, it is just that they aren’t as heavy. I am not going to sell someone an entire body suit that weighs twenty kilos, so I am trying to translate my ideas and ethics into a small development, maybe ten pieces that are easier to actually put on the body. My focus is a soft, lingerie aesthetic. I am experimenting with stretch techniques, so I can get the same feeling of mapping out the body. If you wore a piece and then I wore it, the idea is, that your body would show on my body.

Credits

Portrait Chris Lensz

Photography Sharna Osborne

Stylist Danielle Emerson

Creative Director Jasmine Raznahan