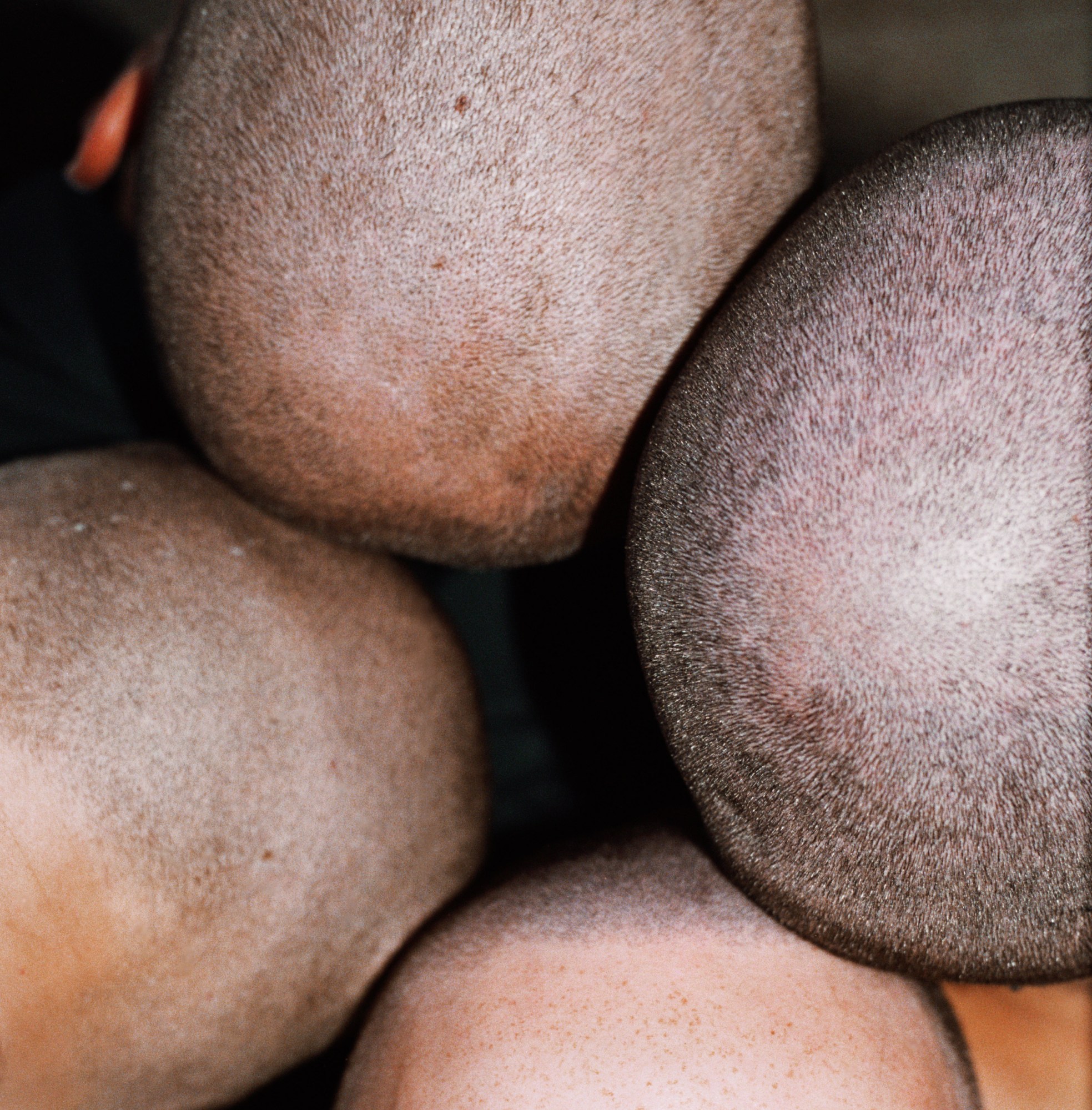

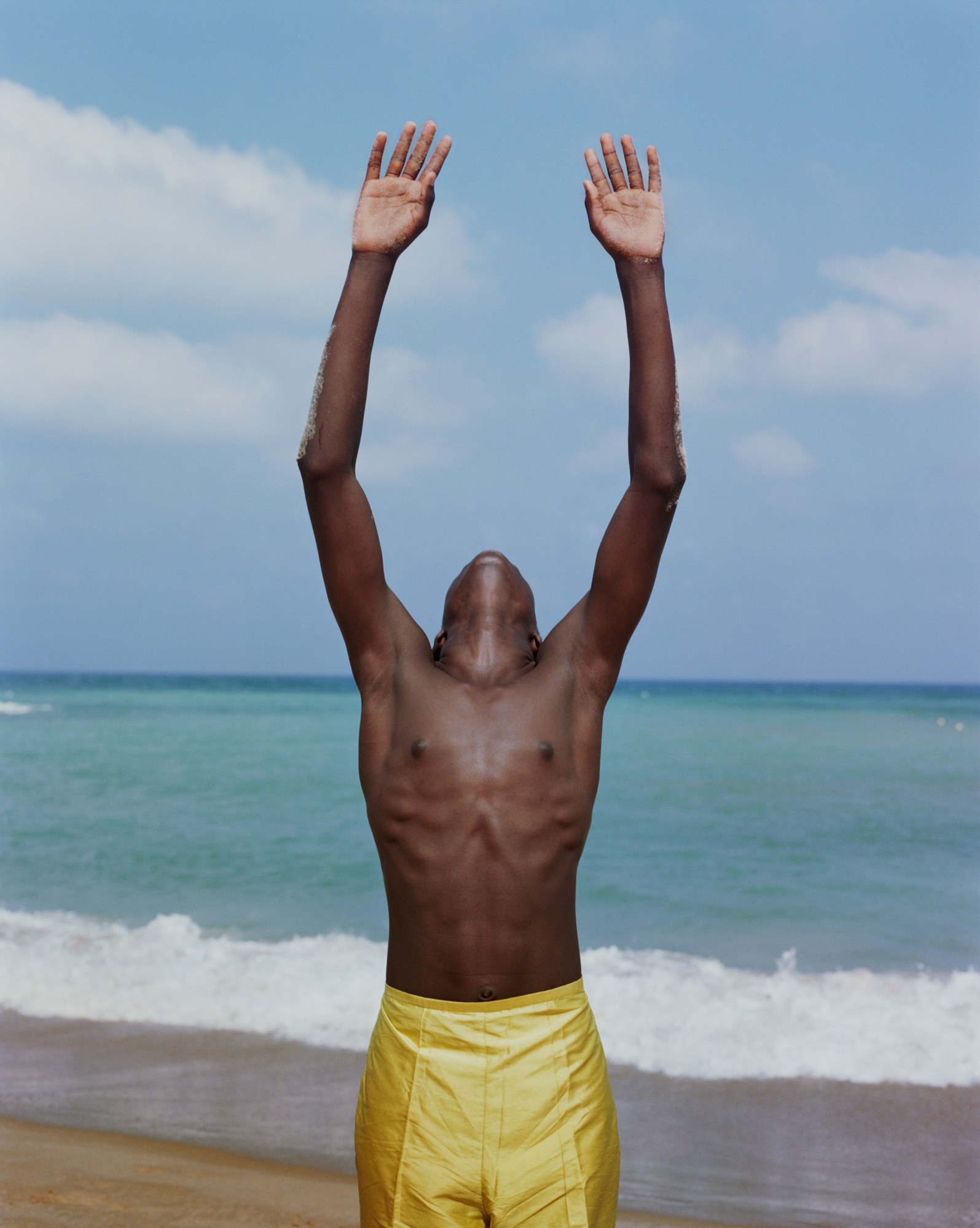

Israeli photographer Dudi Hasson’s work has been published in international editions of Vogue and Vanity Fair, but he started as a self-taught striver. Bathed in the exquisite Mediterranean light, often against sea and sand, his photographs capture the raw vulnerability of his subjects. He focuses on the body: the stretch of a silhouette and the curve of form, from hunched shoulders to shorn heads, from lean torsos to upended butts, from hanging breasts to outreaching arms.

Dudi’s first book, published this month by Libraryman, juxtaposes—with spare beauty—images from his various series and commissions. The book’s title, “As Far As Close,” is based on a Hebrew poem contained within its pages, dreamed up by an emerging poet especially for this project, about the disorienting feeling of occupying liminal space.

In between travel engagements, Dudi discussed the influence of family portraiture, his approach to working with nude subjects, and attempting to let go in the process of grief.

How did you land on photography as your medium of choice?

I started taking photos when I was 15 years old, guided by a somewhat naive feeling, like a first love. I focused on people and moments rather than scenery or objects. My mind was—and still is—constantly generating frames and compositions, constantly observing, imagining how I would direct those around me. I don’t walk around with a camera everywhere; it’s more of an inner burn.

As an autodidact, I had the privilege and bliss of ignorance; it allowed me to really find my own voice and be free of any rules. I drew inspiration from people that roamed the streets: I would go to Tel-Aviv and explore Allenby Street—a big main street in the city that wasn’t mainstream then—with my camera. It was filled with that special mixture of people that exists in Israel, all kinds of characters. I’ve been influenced by different kinds of visual arts, especially cinema, but the street has remained my main influence and even passion.

Did you grow up in an artistic household?

My childhood home wasn’t an artistic one, but it was nevertheless an inspiring one. I definitely gained an aesthetic perspective growing up around women: My mother was a hairdresser who worked from home and different women came and went, each with her own aesthetic.

I love that. How did you shift from photography enthusiast to photography professional? What there a pivotal moment for you?

I started by working in a photo printing store. It was before digital photography; everything was old-school. I was developing and scanning photos for three years. I saw family trips, family portraits, family life. Looking back on my work—especially the images selected and created for “As Far As Close,” being a book that revolves around relationships—I now realize how much those three years in the shop influenced me.

I started making a living off photography at a relatively young age. I was working as an assistant for an Israeli fashion photographer, and I was the worst assistant! Naturally, I was fired. If I had to point to one pivotal career moment, that would be it. Once I was let go, I started to do my own production. I did everything: making the pickups, working on the set decor, styling, the whole process. I submitted every project to Israeli magazines, hoping they’d take it. After magazines liked my work, they started approaching me themselves. As I made a name for myself, I started traveling the world, absorbing inspiration from versatile experiences.

Are the people featured in the images often ones you know well, or models you work with?

Many featured in the book are people I know, many are not: It’s a mix. There are intimate photos of people close to me, friends and their families, as well as people I’ve known for five minutes while traveling, and probably will never encounter again. But with all of them, I shared an unexpected moment.

Can you talk about the role of territory in your work? How does your Israeli identity shape your photographic practice?

The book portrays work from Ukraine, India, Israel, and other places. As an Israeli, I get a lot of Middle Eastern inspiration from this tiny country’s scenery, which combines so many different landscapes: desert, snowy mountains, vast forests, and four different seas. Israel is a complex place, but also a magical one. The astonishingly wide range of cultures, ethnicities, races, religions, and genders is fascinating to me.

What was your selection process for “As Far As Close”?

I already had some sense of what kind of works I wanted to include, but for the first time in my life I sat down and went over all my work—from all over the world, over all the years. This long process made me realize how much my work was influenced by my personal, real-life experiences, and I wanted this to be reflected in the book. I also created new work especially for it.

There’s a poem in Hebrew, alongside an English translation. What is your relationship to poetry? Why this particular poem?

Though I enjoy poetry and prose, I never write. I was always much more comfortable expressing myself through visuals. But I thought something poetic would shine a light on the book’s theme. I reached out to Noam Noy, an up-and-coming young Israeli writer I knew through mutual friends. I told him about my book idea and showed him the work. We started meeting regularly and had long conversations and became close. After coming up with the book’s title together, I asked Noam for the opening text: Not an existing poem that might fit, but something new that resonated with the photographs and this title. When Noam came back with the text, I knew it was a perfect fit.

You photograph bodies beautifully. How do you create an uninhibited environment that facilitates both bodily nudity and tender vulnerability?

I think one of the things that creates an uninhibited environment, in which my subjects can feel comfortable, is that I’m so busy with capturing the moment that I don’t pay any attention to the nudity just as nudity. This makes it easy for the person being photographed to feel the same way: the nudity is not for the nudity itself, but for something bigger. I never remark on anyone’s body and in fact I don’t even look at their body except through the lens. My gaze is always aimed at their eyes; that helps to make it a non-issue. Often, the moment captured creates a sense of fantasy; the nudity is never blunt or harsh.

I love your portrait of Shira Haas. Do you think about portraiture differently with someone who has a public-facing persona—and projections that come with that?

Photographing ‘unknown’ people is indeed different than working with a public-facing persona. Experienced models or actors sometimes tend to be overly prepared; they can be overly confident and bring that public persona forward. My goal is to bring the real person to the front and capture a moment of authenticity.

What obsessions would you say you have?

I’m drawn to relationships in general and towards families specifically. ‘Measuring’ the distance between people is a key element of my work. I find relationships between twins mesmerizing. In the book, there’s a specific ‘chapter’ for which we even changed the paper to distinguish it as a series. It’s a project called Ein Hod, named after the northern Israeli village the photos were taken in. I also photographed my assistant Yasso’s family, in their home and around the village.

What is the symbolism of “As Far As Close” as an overarching title for you?

The book was published a week after my father passed away, after a long-term struggle. This process of saying goodbye to my father created a complex relationship with the book: A feeling of alienation from it was slowly replaced with acceptance.

While having to let go of my father, I was also learning to let go of my fixation of controlling every little detail of my work, like trusting the publisher to arrange the photos and edit the book. Two weeks before the book was printed, I stopped the process—I decided to add a text dedicated to my father, knowing that he probably wouldn’t live to see it. My father died a few days before the book was printed. The birth of the book and the death of my beloved father were both overwhelming. I decided to take some time for myself and to be with my family. Now, after a year of taking it slow, I’m traveling again, working more and more, and my search is now deeper, and more meaningful, than ever.