“You can actually pinpoint the second when his heart rips in half”.

This memorable line was uttered by Bart Simpson in the now iconic 74th episode of The Simpsons episode I Love Lisa, first aired in 1993. He plays back a video of his sister Lisa vehemently rejecting her would-be suitor Ralph Wiggum on national television, pausing the footage just as the spurned Ralph clutches his chest with a grimace of pure anguish. Love hurts, it told us.

Despite its eventual decline, The Simpsons was once a powerful window into American identity, specifically into the petty mores of the suburban nuclear family. In what has become known as its Golden Era (the moniker hardcore fans have bestowed on the show’s earlier, most influential seasons), it deftly exposed the world’s fears and foibles.

Its razor-sharp observations and caustic lampooning of the stock characters in everyday American life made for hilarious viewing, but unlike other shows, the social commentary in The Simpsons was rarely throwaway. It was only later we realised how astonishingly prescient and insightful the writing was — there is now a whole catalogue of absurd (at the time) predictions that The Simpsons got right, like that time future-Lisa replaced President Trump. While the Simpsons has expertly satirised everything from class struggle (remember Marge’s stint at the country club in her mangled Chanel suit?) to society’s fatal complacency about climate change (see The Simpsons Movie), its most piercing revelations were about something more personal — love.

I Love Lisa was the Simpsons’ first foray into Valentine’s Day, and in this masterfully constructed cartoon is everything we need to understand capitalism’s favourite pointless holiday. The episode opens with KBBL radio mistakenly playing Monster Mash, a Halloween song, instead of a love song. The radio presenter Marty feebly attempts to disguise his mistake by arguing the song could be relevant to the holiday — his awkward attempt to shoehorn love into a place it clearly doesn’t belong, we will understand as the episode progresses, is a mirror of the self-delusion we all perform in relationships under capitalism, as we desperately try to attach a cart to a horse that just wants to run away.

In the next scene, Abe Simpson dismisses Valentine’s as “another Hallmark holiday designed to sell cards” — then moments later begs for the envelope from another old man’s card. This opening moment sets the tone for the message of the whole episode — Valentine’s is a terrifying window into the conflicting desires at the heart of how we relate to other people. We know that the performative notion of perfect love represented by Valentine’s is a sham, another capitalist hoop we’re expected to jump through; but equally, what we crave more than anything in the looming shadow of death, is simply to not face it alone. Love, The Simpsons tells us, is little more than that; a symptom of our desperate yearning to be anything but by ourselves.

“As Ralph advances and Lisa recoils, we understand the asymmetry at the heart of every relationship (especially heterosexual ones, but other types too); we are all coming from different social and political spaces, and no matter how hard we try, bridging the gap between the personal histories of two people is almost always doomed to fail.”

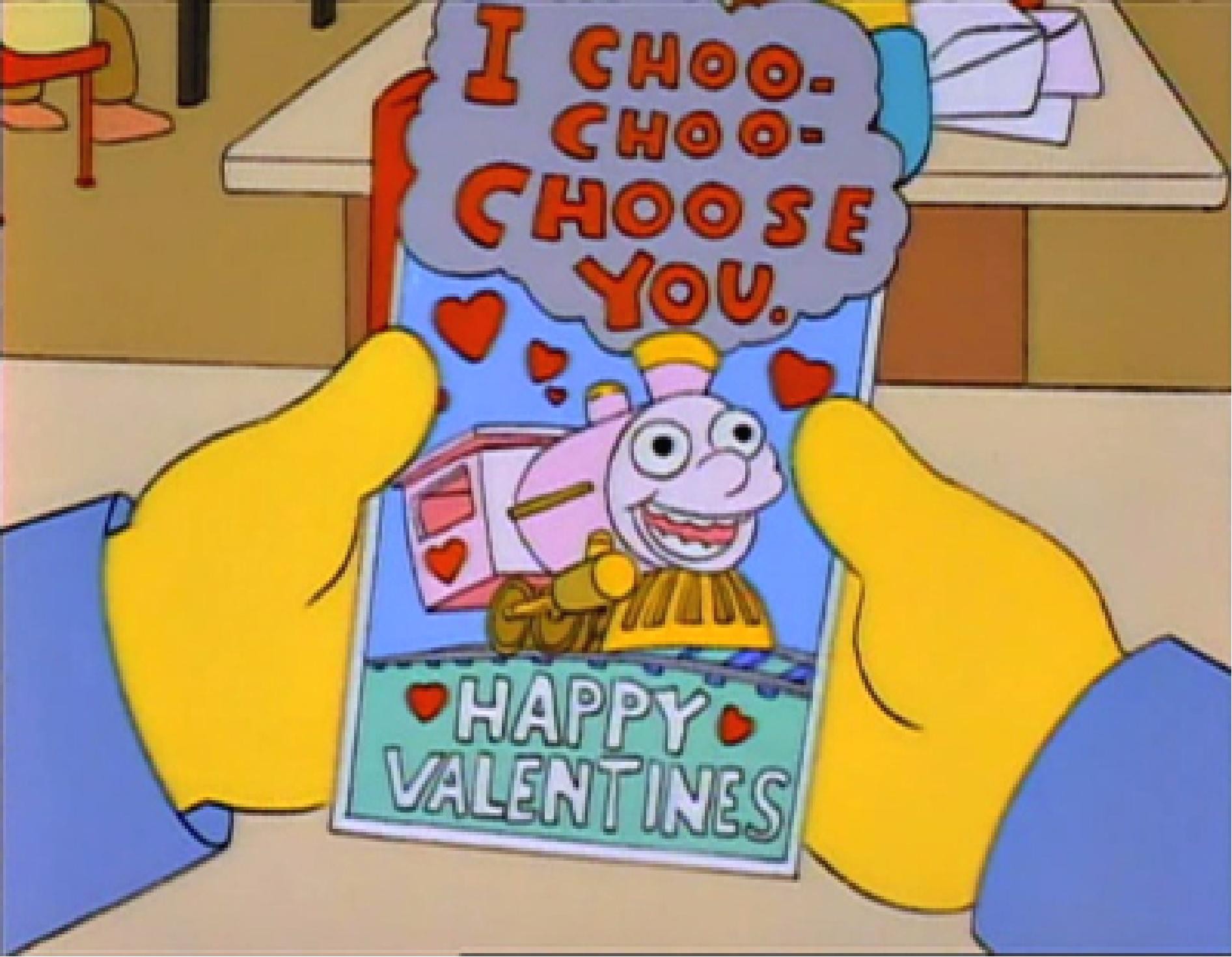

As the episode progresses into its plot proper, we enter Lisa and Ralph’s classroom. Ms. Hoover admits to assigning the students “pointless busy work” in the name of Valentine’s, an occupation which ultimately leaves Ralph in tears when he doesn’t receive any handmade cards. Lisa, taking pity on the companionless boy, offers him hers. It’s beautifully crafted and with clever artwork, but the apparently painstaking care with which she constructed it belies the indifference she feels toward Ralph as a person. The sentiment at the core of Lisa’s card, “I choo-choo-choose you”, is a lie — while it lays claim to a sense of certainty about its recipient’s character and his suitability to her as a partner, the material reality is that Lisa was simply wearing these feelings of certitude as a costume. Ms. Hoover assigned her a task, and in her eagerness to please her capitalist overlord (in this case, the teacher who is training her to be a subordinate servant of the industrial machine), she executed an excellent facsimile of real emotion.

In this way, Lisa is a metaphor for all of us on Valentine’s Day: capitalism certainly invented this holiday to sell mindless gifts, but it also invented it to condition us into the lie of traditional love, and to aspire to that “useful” ideal. The fundamental unit of capitalism is, after all, the nuclear family: a small engine which allows the individual parents to continue supplying their labour while training their offspring to do the same. On Valentine’s, just like Lisa, we are told to rehearse and aspire to traditional love, so that some day we will slot neatly into the matrix of productive, obedient couples.

Lisa is excellent at pleasing people. But as good as her fake sentiment is, it is more a symptom of her socialisation into the role expected of a woman in capitalism — i.e. to perform emotional labour for men, to tend to their fragilities. This concept was made famous by Arlie Hochschild’s 1983 book The Managed Heart — capitalism pushes women into roles which require the selling of emotion, e.g. nursing, air stewarding, etc. Lisa saw Ralph was alone and felt it her duty to placate his misery. Later, as she realises what committing to this role would really mean, she is horrified, and wrenches back from what she perceives as a morbid future with a wormy partner.

Ralph’s return of the sentiment is equally false — he “chooses” Lisa back not because of some electric connection between them, but because she presented herself as the only one willing to tolerate him. His pathetic attempts to forge some connection on their walk home from school — “So… do you like… stuff?” — is an indictment of how, as humans, we are more concerned with not being alone, with finding the bland, stable partner capitalism demands we find, than with discovering a kindred spirit who sets our soul on fire and enriches our lives.

Later, as Lisa attempts to hammer home to Ralph’s stubborn brain that she isn’t interested, the men in Ralph’s life (namely his witless father Chief Wiggum) assure him that women want to be pursued — another heteropatriarchal capitalist lie that tortures women. “Win a mate at any cost,” capitalism whispers in the credulous male ear.

As Ralph advances and Lisa recoils, we understand the asymmetry at the heart of every relationship (especially heterosexual ones, but other types too); we are all coming from different social and political spaces, and no matter how hard we try, bridging the gap between the personal histories of two people is almost always doomed to fail. This is explored in multiple other Simpsons episodes, through the lens of class as well as gender; when Lisa falls in love with Nelson in episode #160, her attempts to groom and intellectualise him collapse spectacularly. In episode #122, when she sees a vision of her future engagement in the fortune teller’s tent, the snobbish man she meets at university cannot lower himself to slot into her humble background. Even when The Simpsons tells tales of superficially “successful” relationships, like that of Homer and Marge, it dissects the misery behind the pretence. In that episode where Lisa wants to change Nelson and asks her mother for advice, Marge assures Lisa that she has built Homer into a better person — something the audience knows not to be true. Marge, like Lisa, is performing the role capitalism expects of her, indulging a man who consistently drains her of energy and optimism while she props up the family unit with backbreaking false happiness.

And so we come back to that most iconic moment, when Ralph’s heart breaks on live television. It tells us the inevitable result of trying to achieve the heteropatriarchal ideal that Valentine’s Day espouses is, at best, heartbreak. That’s right, the best result. The Simpsons repeats this morbid mantra throughout the series, via its peripheral characters and subplots (Moe and Helen Hunt… err, I mean, Renee…, cheating Apu and Manjula, Kirk and Luann Van Houten). The worst result isn’t what we see played back in slow-motion by Bart — the worst result is being trapped forever.

Lisa has repeated bleak visions throughout the series of being married to Ralph, of being married to Milhouse; she realises that what is worse than heartbreak is living with someone your heart can’t even break for. Perhaps this, the most hellish future, is represented in the spine of the whole Simpsons: the marriage of Homer and Marge. At least Kirk and Luann eventually broke up…

More than 25 years after this episode first aired, its cynical view of Valentine’s Day and the limiting options offered by its capitalist understanding of love still proves a sobering lesson.