When Studio Ghibli’s co-founder Hayao Miyazaki announced his retirement back in 2014, it was rumored that the Japanese animation house was dead for good. However, just eleven days ago it was revealed that When Marnie Was There, a film largely believed to be the studio’s last, will receive an official UK release on June 10th. Even more exciting is the news that Dutch filmmaker Michael Dudok has been hard at work creating a new feature which cites the studio’s other co-founder, Isao Takahata, as its artistic producer. Entitled The Red Turtle, the film will make its debut at this year’s Cannes Film Festival and will be officially affiliated with Studio Ghibli, proving once and for all that there’s life left in the animation giant. Over its 30 years in business the studio has spawned the highest-grossing Japanese film ever in the form of 2003’s Spirited Away, which generated $300 million profit worldwide and bagged a prestigious Academy Award for Best Animated Picture. 1997’s Princess Mononoke was a similarly pivotal release which, until Titanic came along, held the record for the most successful film in Japanese history. Studio Ghibli is responsible for eight of the fifteen highest-grossing films to ever come out of Japan and the excitement surrounding new releases show there’s still demand for fresh material — but what is it that sets Ghibli apart and gives it such enduring international appeal?

One common thread that links Ghibli films is the inclusion of varied female protagonists; a far cry from the outdated stereotypes favored by Hollywood giants. Princess Mononoke is unique because it takes the ‘dependent princess’ narrative and flips it entirely; as opposed to a vulnerable damsel in distress, San (known to humankind as ‘The Wolf Princess’) is actually a feral heroine fighting to defend her forest homeland from destruction. She is often violent, short-tempered and aggressive — you know, because she was raised by wolves — but there’s an underlying complexity and compassion that make her one of anime’s most interesting characters. Lady Eboshi is similarly contradictory; she has all the stereotypical qualities of a villain yet spends her spare time rescuing local women from human trafficking and even provides refuge for victims of leprosy.

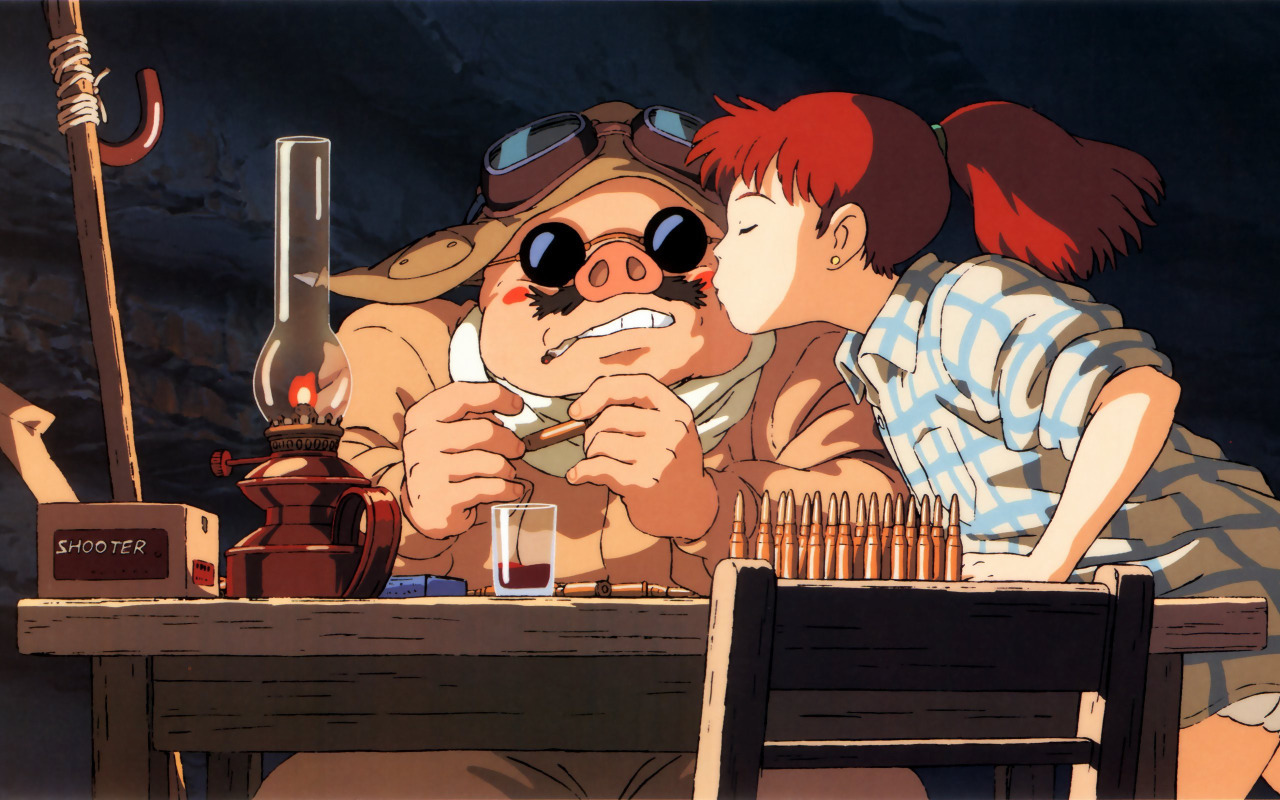

There are more relatable examples of feminism too, like Only Yesterday‘s Taeko. A young, unmarried woman living in Tokyo, she faces constant pressure from her family to settle down and follow a ‘traditional’ route to love. Instead, she turns down a marriage proposal and decides that she’s happy to do things on her own terms. These women break the connotations of gendered occupations too; instead of stay-at-home mothers, the directors at Studio Ghibli prefers to create female mechanics or witches as their protagonists. Porco Rosso‘s Fio is the 17-year-old granddaughter of an aircraft designer left in charge of the family business and, naturally, is initially met with skepticism due to her age and gender. However, as the film progresses she gains respect and proves abilities and even manages to avoid romantic involvement altogether — basically unheard of for a female character in the film industry. Probably the reason that Studio Ghibli is so popular is that it provides an antidote to Disney’s saccharine heroines, instead feeding audiences aspirational female role models with talent and substance.

The element of fantasy is another key factor in the success of Studio Ghibli — its most successful films are brilliantly bonkers, combining evil spirits and greedy old hags with magic dumplings and Buddhist cults. Regardless of the presence of mythology and spirituality, each film comes complete with a moral message that results in a relatable human touch. Princess Mononoke, for example, is actually a story designed to highlight the destruction of natural resources by mankind, whereas elaborate online theories have argued that Spirited Away covertly touches upon themes of prostitution and the corruption of children. In a film industry usually dominated by clichéd love stories and low-rent rom coms, the immersive worlds of Studio Ghibli obviously resonate with a global audience looking to be challenged and presented with heavy topics. Animation is often written off by the film industry due its link with children’s films — unsurprisingly, Ghibli films with child leads are often dismissed by foreign audiences as ‘too cute,’ whereas in reality they deal with issues such as pacifism in war and eco-terrorism. There’s also Kiki‘s Delivery Service, a surprisingly touching film that documents the childhood of a young witch (accompanied by her black cat Jiji) struggling to master her natural abilities. Kiki meets the elderly owner of a bakery and subsequently sets up her own delivery service that goes well until she loses her flying abilities. The aesthetic may be light-hearted, but Kiki falls into a bout of depression — making Kiki‘s Delivery Service arguably one of the first anime films to actually tackle the mental health issues triggered by adolescence.

While the anime film industry may still be viewed as a niche market by foreign audiences, the continued success of Studio Ghibli proves that it can resonate worldwide when done right. Its success may be largely due to the progressive attitudes of its co-founders Takahata and Miyazaki — their emphasis on layered female characters sets them apart in a film industry dominated by archetypes of femininity. The Ghibli heroines are varied and each powerful in their own way; they struggle with depression, peer pressure and social judgement yet overcome these issues in their own unique ways. Underlying messages of morality give these films endless repeat potential and, crucially, make their audience consider larger issues in the modern world such as mental health, the potential of pacifism and the lasting impact of human greed on the environment around us. The Red Turtle may only be a co-production, but the anticipation surrounding its release only serves to underline the importance of the studio’s lasting legacy. It’s widely argued that the productions won’t be the same after the departure of Miyazaki — and it may well be true. All we know for sure is that the Japanese film studio may still have a few international hits to come.

Credits

Text Jacob Hall