In 1930, a group of the French elite gathered together in the courtyard at the end of the Rue de Babylone in Paris – at the foot of the townhouse of Count and Countess Pecci-Blunt. It was to play host to the duo’s extravagant ‘Bal Blanc’, or white ball, hosted in conjunction with American artist Man Ray. The dress code, as expected from the event’s name, was strictly white. As the guests arrived, dripping in diamonds and pearls, a projector erected from the window of the mansion and played a hand-coloured film by Man Ray, throwing waves of moving colour and imagery across the visitors, as they danced alongside the live band. The effect, according to Ray’s autobiography, was “eerie and fantastical – as if the guests had become moving screens themselves.”

It is perhaps, one of the earliest meetings of fashion with film – a partnership that we continue to see grow and evolve. But why have those two f’s become such great friends? Look to the employ of leading fashion houses for the costumes of some of our biggest Hollywood films to see just how much the runways have infiltrated the reels of film. Why? Ultimately, like the majority of things, it’s driven by money. But with money comes desire, and the pairing of fashion and film actually speaks broader of our wider creative desires.

If we think of some of film’s iconic inclusions of fashion we can start to answer that aforementioned question. In 1963, Breakfast at Tiffany’s debuted, with a leading look designed by Hubert de Givenchy. The floor-length, sleeveless black gown, with rear cutout décolleté is perhaps one of the greatest images of fashion in film, securing the little black dress a place in the modern-day woman’s wardrobe. The dress, as has been highlighted in the book The Audrey Hepburn Treasures “visually defined the character but indelibly linked Audrey with her.” So the LBD was born and women of the world flocked to Givenchy’s maison in Paris to buy a piece of the Hepburn look.

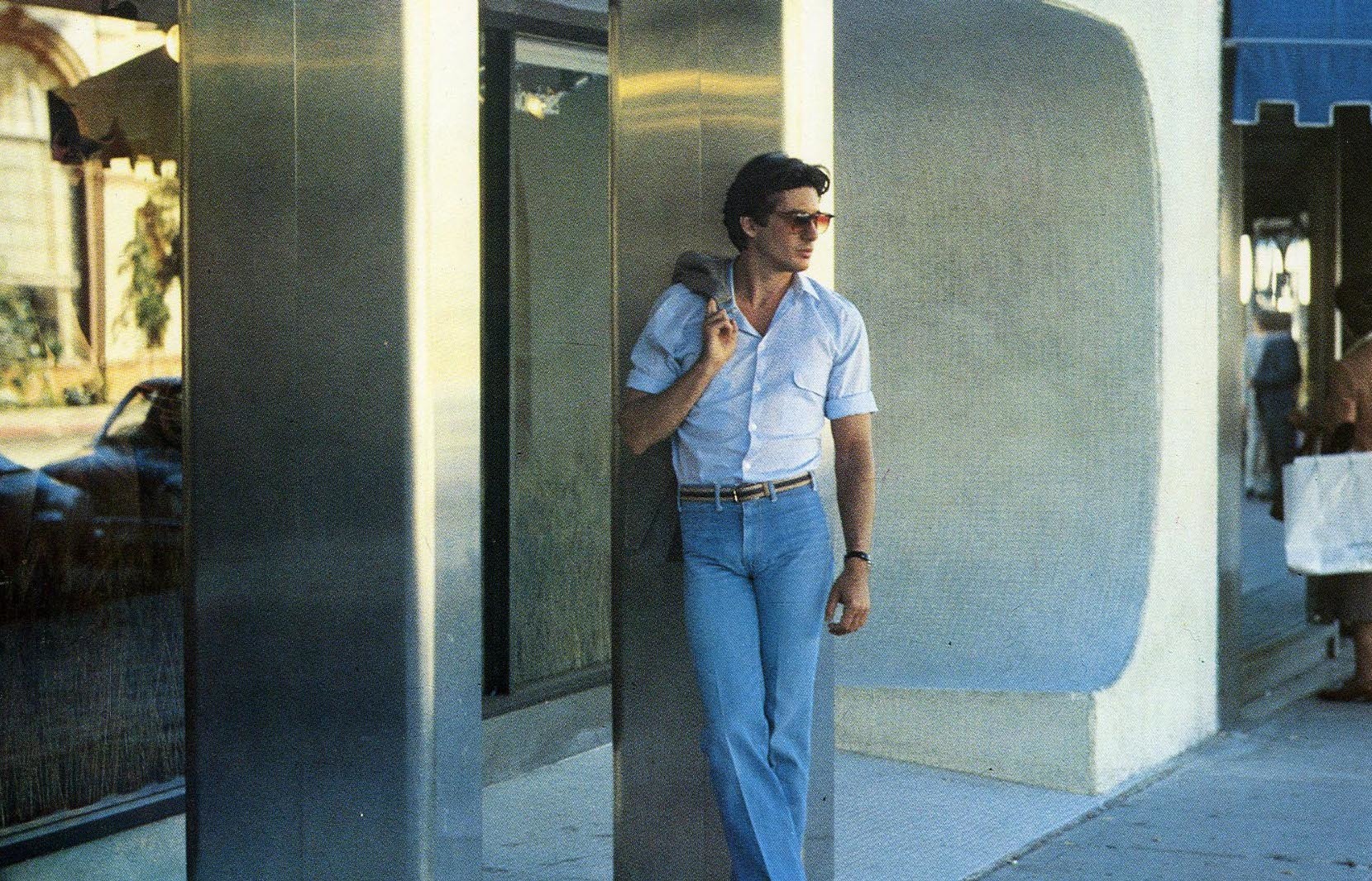

The clothing of 80s classic American Gigolo achieved a similar status, with the majority of the costumes provided by Giorgio Armani. Depicting the life of Julian Kaye, a male escort in Los Angeles played by Richard Gere, the film successfully adjudicated an alteration within menswear. It liberated the stuffy, structured tailoring of Savile Row, providing an antagonist in the form of loose-fitting linen suits and separates from the hand of Mr Armani. An obviously attractive Gere is used as a mannequin for Giorgio’s clothes, aligning them with the lifestyle he portrays. What man would not want to buy into the clothes that “leave women feeling more alive than they’ve ever felt before,” as the film’s poster suggests. Gere’s impact on the Armani brand was so important that it’s rumoured he could still walk into its stores and leave with anything from the rail.

These examples can be aligned with what writer Guy Debord identified as the society of spectacle, a world dictated by images and signs. Debord said that commodity is informed by the context in which it is presented. Hepburn’s association with love and luxury, and the Armani suit with sexual liberation, reinforced by the celebrity status of their wearers. Interesting then, that both these iconic sets of cinematic clothing help portray some form of sexualised protagonist.

So is it about sexual appeal? Do we crave that effortless image that Hepburn and Gere exude? Of course. But it’s not just sex that is governing the desirability of those garments. Sure, it plays a role, as sex does in the majority of fashion. But that’s part of a wider idea of fantasy that both fashion and film set out to establish as part of their remits. After all, great fashion and great film set out to achieve the same thing – great story telling. Look to Galliano and McQueen – masters of narrative. Fashion can borrow from the fantasy of film, as film borrows from the tangible reality of fashion.

It’s perhaps why we’ve seen designers directing major blockbusters and A-list directors producing fashion films. Tom Ford’s cinematic interpretation of Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man is a prime example. Argued by many as a two hour long promotion of the Ford brand, the film does indeed see its lead characters dressed in the director’s suiting, alongside Nicholas Hoult, who also modelled in the designer’s 2010 ad campaign. Stylistically, the film mirrors the modernist aesthetic that Ford loves – set amongst slick redwoods and California’s Frank Lloyd Wright inspired mid-century modernism. The effect is something that feels less ephemeral than the constantly changing fashion seasons in which Ford presents, cementing the entire brand into visual history.

So what then of the continued involvement of fashion in film? Are we being continually conditioned to purchase as we sit in the cinema for two hours, eyes ablaze as colourful imagery dances across our eyes? It all sounds a bit manipulative, no? Of course product placement has its part to play, but the real value of fashion and film comes back to that joint ability to tell stories.

In Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation of The Great Gatsby, Miuccia Prada worked alongside costume designer Catherine Martin and Brooks Brothers to dress the characters of the film. Rather than immortalising a specific garment in film history, or becoming a feature length advert for the Prada brand, the clothing enabled the modern day viewer to re-connect with the original F. Scott Fitzgerald story. The clothing and bohemian visual artistry of Luhrmann marry so effortlessly together, presenting atmospheric swathes of colour and party grandeur, that seems not dissimilar from those earlier descriptions of the ‘Bal Blanc’. Indeed, Martin said of the clothes that the aim was to “feel how it must have felt to hear jazz for the first time at a party. In order to feel how scintillating, extraordinary, new and dynamic these things were, there needs to be a frisson of the new for people to actually understand.”

And that’s what fashion does so well when done correctly on film – present the latest fashion. When that’s mixed in with any form of artistry, it aids our understanding of the subject matter and alters the way in which we see things, helping to give it identity and credibility. From a creative perspective, that’s a pretty powerful tool. And if perhaps we sell some clothes on the way? Well then so be it.

Credits

Text Greg French