Over the past month, I have ripped apart mismatched socks and rearranged them into three colourful, patchworked crop-tops. It was inspired, in part, by the upcycled fashion that has infiltrated every corner of our FYP and explore pages in 2020. From tops made of vintage scarves to thrifted hoodies, sold by creators from London to California, these garments all follow a similar aesthetic: combinations of textures, fabrics, and colours stitched together with copious amounts of thread and an overlock stitch.

Patchwork is a direct product of our time, influenced by everything from the growing sustainability movement to the return of Y2K style, but this DIY aesthetic has particularly boomed during the pandemic. With nowhere to go and no one new to see, many of us have spent the past six months clad in old sweatpants and oversized hoodies, unsure of how to fill our days. At first it was fairly cosy, but time spent in the same setting, recycling the same outfits, became stifling, isolating and left little room for expression of creativity or individuality. Combined with the endless amount of free time on our hands, this has prompted a resurgence in craft hobbies: learning to sew, crochet, embroider and tie-dye seem to be high on the list of ways to pass the time. And if the countless “how-to” videos on flipping thrifted clothes and re-working old garments on YouTube and TikTok are anything to go by, this crafting obsession is happening on a global scale.

It’s unsurprising that we’re craving unique fits in reaction to the ubiquitous loungewear look, but lockdown-induced DIY goes beyond teens sitting at home reworking old shirts. Patchwork-style clothing is showing up in the designs of fashion brands around the world too: cult labels like ASAI and Eckhaus Latta have become known for their own original takes on patchworked pieces that feature visible overlocking.

Examples of the practise have been threaded through the history of fashion: a similar deconstructed aesthetic was popular in the 90s, with looks from brands like Maison Margiela and XULY.Bët featuring hanging threads and exposed seams. Both labels were known for reworking and upcycling fabrics, and are some of the earlier examples of sustainability in the fashion industry.

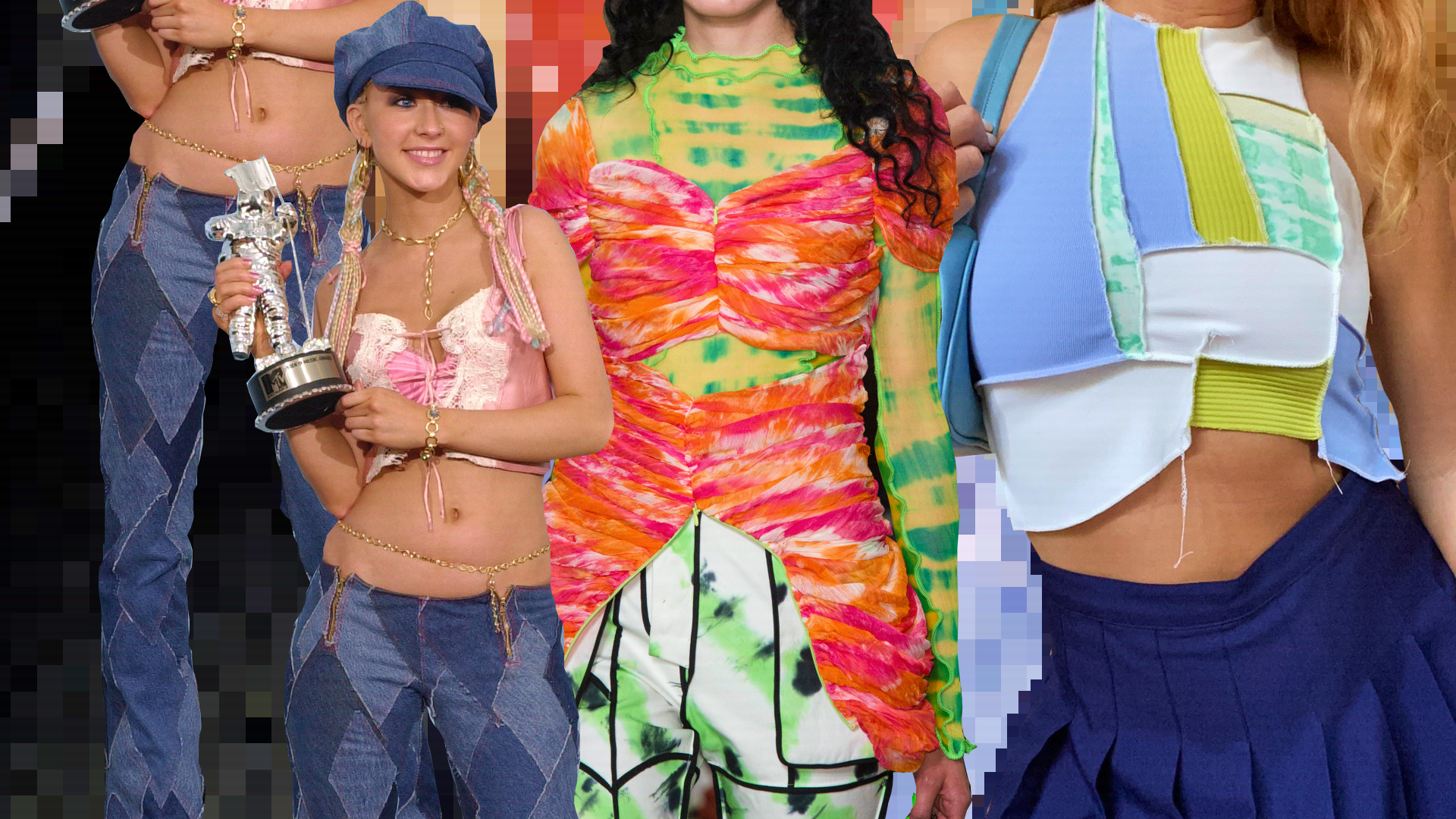

After this DIY aesthetic had successfully taken over 90s catwalks, a more mainstream version blew up as we moved into the early 2000s and patchwork denim became mandatory popstar wear. Remember Christina Aguilera wearing Zana Di patchy jeans with a big denim hat? How about that iconic Britney and Justin all-denim moment? It was the era of velour sweatpants, low-slung jeans, and bedazzlement, during which brands like Juicy Couture, Von Dutch and Baby Phat were the go-tos. As we are witnessing, Y2K style is having a resurgence in popularity thanks to recent noughties nostalgia.

Beyond having a lot of time on our hands and a penchant for anything reminiscent of the early 2000s, there’s another concern looming above that of the pandemic that has without a doubt impacted the sudden explosion of the patchwork trend — the climate crisis. With an emphasis on putting discarded fabric to use, this style speaks to the need (and increasing desire) for sustainable fashion. As we wake up to the damage we are doing to the Earth, there’s an enthusiasm for real change, both within the industry and the choices we make as individuals.

Maddy, the creative behind maddypageknitwear (a Top Seller on Depop with over 20k followers on Instagram) said she started her brand by collecting unsellable clothes from the charity shop she worked in and turning them into unique pieces. Since her business has expanded, she’s turned to deadstock and “end of the roll” fabrics in order to meet demand but still remain environmentally conscious. Discussing the importance of sustainability in the fashion industry, Maddy believes that “big retailers have a lot to learn from small, environmentally conscious brands”.

Similarly, Kim, the creator behind kustomsclothing also creates patchwork pieces out of recycled materials. When asked about how sustainability fits into her brand, Kim said that she often sources secondhand and saves fabric scraps to upcycle in order to cut down waste and combat the fashion industry’s negative environmental impact. “The process of turning what is effectively waste into something that people want to buy definitely challenges me creatively,” says Kim. “And more often than not, these pieces end up having the most character and tend to get the most positive responses from my followers.”

Reflecting both a return to homemade craft and the urgent need to preserve the environment, this patchwork trend represents everything that fast-fashion opposes. It is inherently slow-fashion. As people increasingly choose to construct their own clothing, or purchase from brands that upcycle fabric and emphasise sustainability, perhaps the fashion world will start to shift away from the overly fast-paced culture of clothing consumerism. Or perhaps these crafty looks will eventually get mass produced and join the trillions of pounds of yearly textile waste. Only time will tell.