When thinking about erotic art or photography, we often imagine it as a genre charged by the male perspective and created for the sake of eliciting visual pleasure. But what if topics pertaining to the body, pleasure, fetish objects and self-discovery could be approached differently? What if they could be broached through an empathetic, powerful, celebratory female-centering gaze? Atom, a collaborative book from artist Ekaterina Bazhenova-Yamasaki and leather brand Fleet Ilya offers just that, challenging traditional ideas around, and depictions of, the female body and leather garments. It’s a fluid and gentle preservation of experiences of vulnerability and introspection, power and joy, and discovering the potential of the second skin.

Atom came to life in the winter of 2020, when Ekaterina was stuck in London in the midst of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unable to return to Los Angeles, where she is currently based, she had to confront physical and mental isolation. Thankfully, she could turn to a collaborative project with Fleet Ilya.

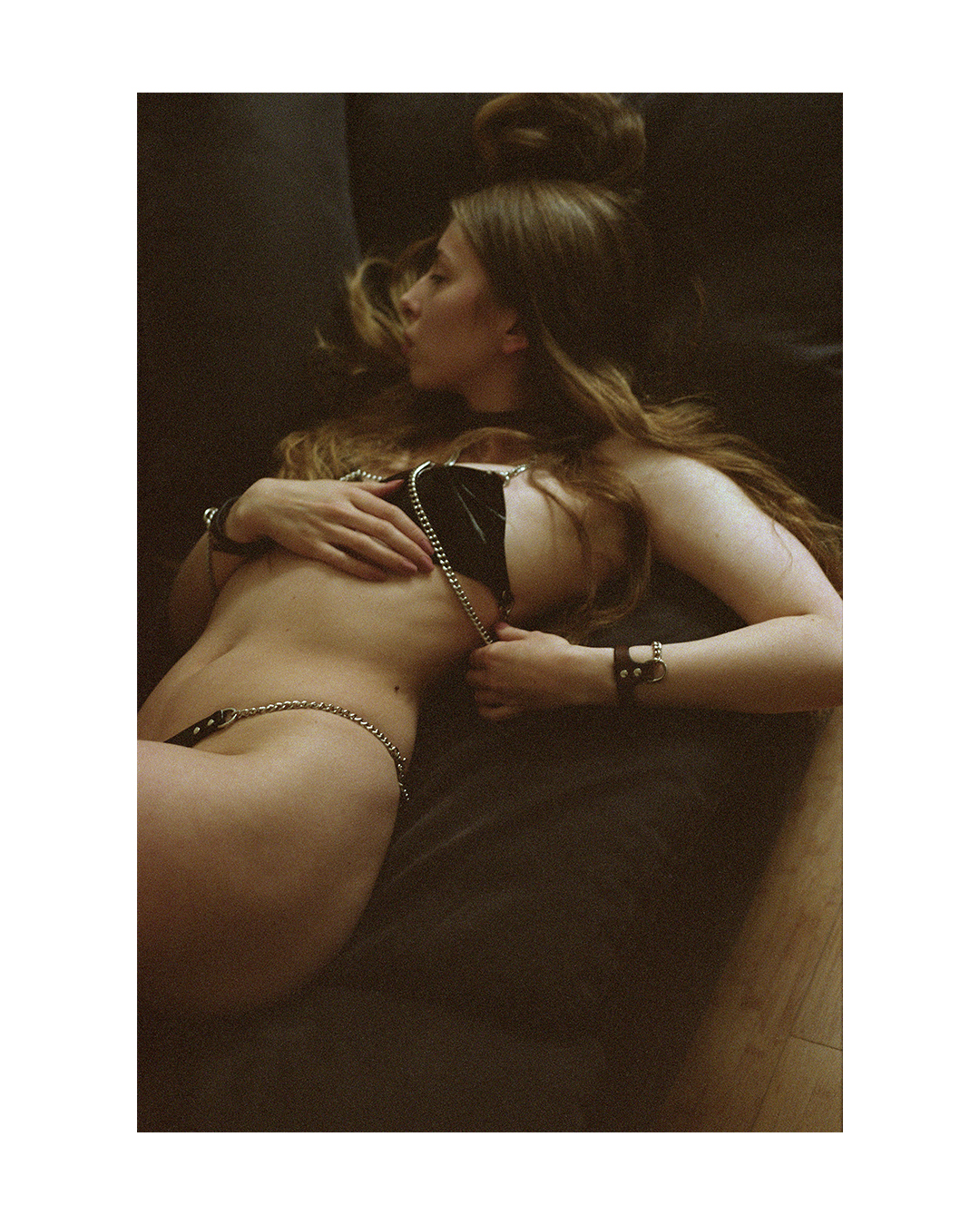

Ekaterina and Fleet Ilya founders Ilya Fleet and Resha Sharma (who also edited the book) have known each other for almost a decade. The London-based label was established in 2003 and focuses on handcrafted leather pieces at the intersection of fetish and fashion: harnesses, collars, belts, headpieces, whips, cuffs and leather lingerie. In Atom, Fleet Ilya’s pieces become tools of self-discovery, intimate connection, and collaborative creativity.

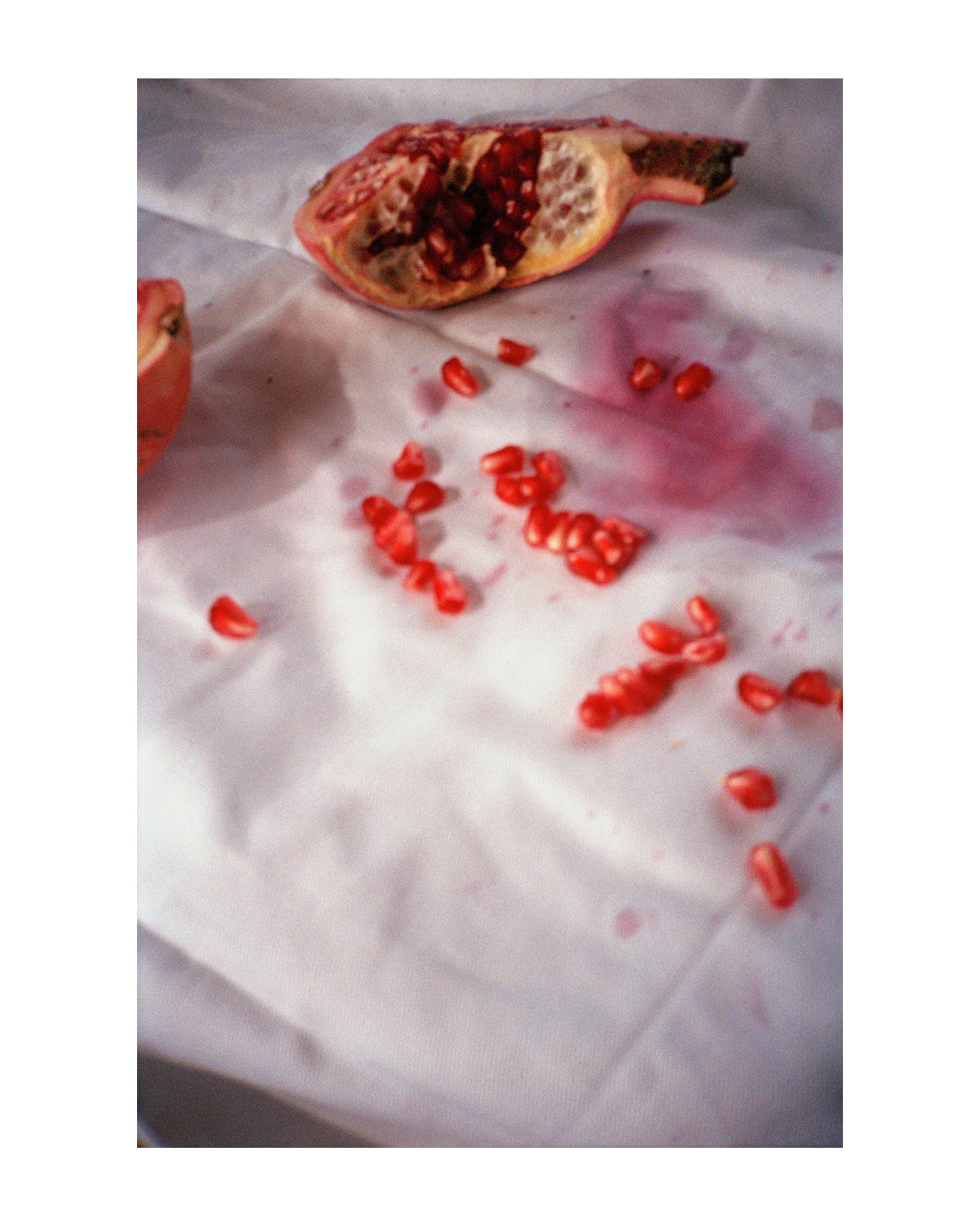

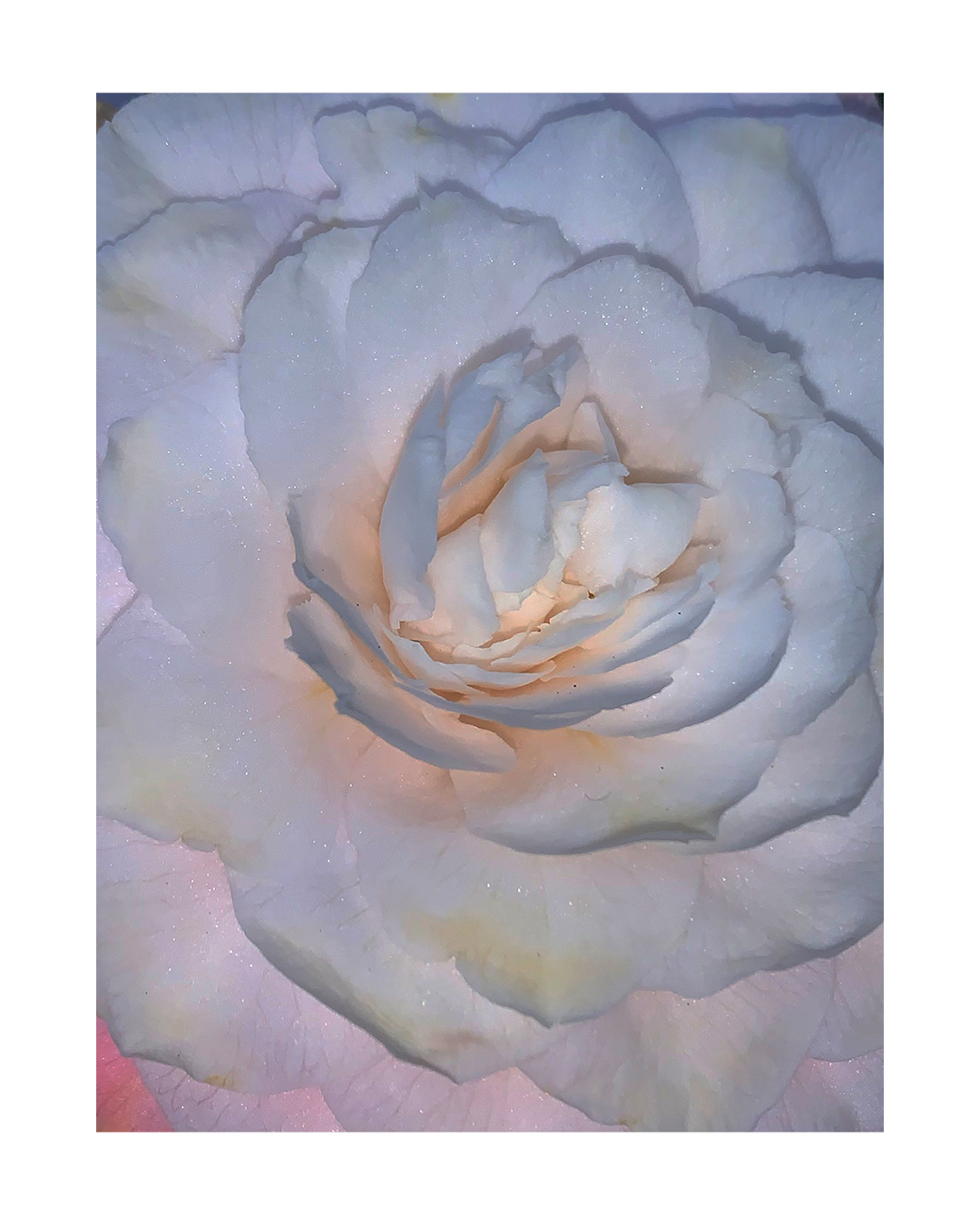

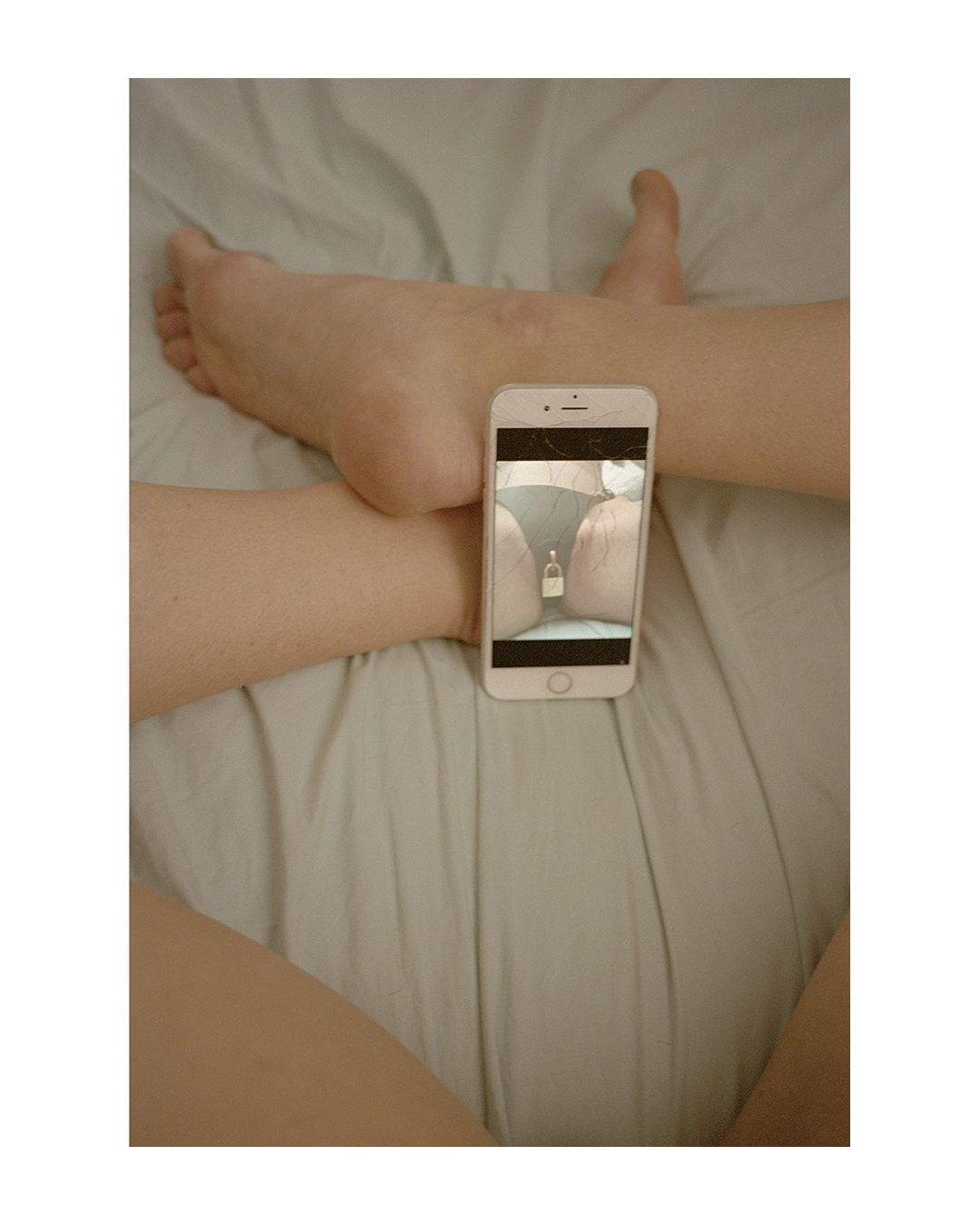

Over the course of making the book, Ekaterina photographed four London-based heroines (and herself) wearing leather pieces in their private spaces. She focuses on their momentary experience of leather and self in this intimate yet exposed environment. Portraits are combined with still-lives and poetic texts specially written for the book by Beata Duvaker. It is an intricately beautiful reflection on the body, leather, eroticism, sexuality and self-reflection in our turbulent times.

With her book launching this week, we sat down with Ekaterina to discuss the female gaze, the body in art, and reinventing erotic photography for the current era.

Could you tell us a little bit about Atom and how the idea of the book emerged and developed?

Atom is a very poetic project which explores loneliness and self-acceptance in a particular environment at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s about the loneliness we all craved but could never imagine going through in this kind of circumstances. When we were working on the book with Resha, our aim was to create something which wasn’t about the imagery, but more about the feeling. When you look through the portraits of women in leather, still-lives and Beata Duvaker’s poetry, you go through this experience page by page. And if we’re talking about the physicality of it, I really wanted to create something textural, that’s why I’ve chosen this kind of cover and included very fragile, translucent pages.

How did you connect with Fleet Ilya and how did your collaboration work for this project?

I have known Resha and Ilya for almost 10 years, and we have collaborated on still image and video work before. We have the same outlook on craft and design, and I love their perspective on the female body in relation to their designs. Everything they produce is made-to-order, which makes a big difference in how the object feels compared to other wearable items. We’re also all interested in the relationship between pleasure and restraint, restriction and liberation, in relation to leather. It’s about self-discovery through the wearable object. Atom as an idea has been developing for a long time, but we had finally got the time to reflect on it and do it over lockdown.

What did you like most about working with the leather pieces for this project?

The leather pieces are central to the project. It’s about how the material and the garment makes you feel, how chains and straps can change your posture, how they come in contact with the models’ bodies, and how they experience it. For me, it’s not about that final pleasing imagery, it’s about the experience of wearing these pieces or being in that environment at that time.

Photography and the body have a really complex relationship — the body in front of the camera often becomes objectified and devoid of agency, especially in the erotic context.

I totally agree. When it comes to other art forms like performance, the body is a tool and it’s not about the body itself. But when it comes to photography or still image, the body is an object. It is a commodity in our society generally speaking, and you do invest money into this commodity, especially when it comes to women. The female body has been a commercialised object for a long time.

This object-like quality and commodification — are these things you try to go against in your work?

As any artist, when I create, I liberate. It sounds tacky, but for me it works like that. I can’t say that I go against it because I’m a human and I have a desire for the body and observing the body. But I’m not doing it for the sake of visual pleasure, I’m doing it for the sake of experience. For myself, the people I’m working with, the viewer. When it comes to the resulting image, it’s up to the viewer how they perceive it: whether they like or dislike it, or simply walk away from it.

How do you bring more subjectivity from the people you photograph into the image?

I do pay very close attention to the person and his or her or their personality. We have conversations before or after. To me it’s about exchanging energies — their personalities unavoidably leave an imprint on the work.

While working on this book, have you looked into the history of, or references connected with, fetish photography? And have you found the medium challenging?

Fetish photography, as part of a broader category of erotic photography, is still a predominantly male field and a tough subject to work with. There are certain stereotypes connected to it as well. When I was doing research, I was looking more into paintings. The still-lives were actually much more complicated to produce because they have strong symbolism, and I had to think carefully about how it would to work with photography of the body. But generally, as a woman, I do know what I want to avoid in erotic photography and what I don’t want to see.

In recent years, the online censorship of work related to sexuality and the body has been on the rise. How do you feel about this in relation to your practice?

It’s tough. I really don’t like it, it disturbs me a lot. That’s why I turned to the classic solution of producing a book. I feel much more protected and comfortable when it’s in the form of a book, rather than single images. Generally, it feels like an endless fight which brings a lot of frustration. But making a book is suitable for me because you get more of an incentive to look at the project as a whole.

You have a few self-portraits in the book and you’ve worked with this genre before — why is it important for you?

Coming back to erotic photography as a male-dominated subject, I never put myself above the people I photograph. I am not an observer, I’m one of them. There is no difference between my body and other women’s bodies. It’s being in the circle, a unity.

‘Atom’ launches at the ICA in London on the 17th of February, and the book can be pre-ordered here.