Although the female nude, which dates back to the very beginning of art, has been a favourite subject of male artists and audiences alike, the work of lesbians has gone largely ignored. With the advent of the Women’s and Gay Liberation Movements of the 1970s, a new generation of artists came to the fore — but queer stories were still largely coded in gender rather than sexuality.

When Harmony Hammond organised A Lesbian Show in 1978 at the Green Street Workshop in New York, painter Jodi Price was told in no uncertain terms by her art dealer that “if she exhibited as a lesbian, she could say goodbye to the gallery’s representation of her work”.

“The contemporary project for lesbians has been to free ourselves from this [male] gaze and reconfigure the terms of lesbian erotic representation,” Harmony wrote in 2000 in Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History. Seeing a new generation of queer female artists emerging, Harmony understood the new millennium would bring forth an era in which “the lesbian artist is going where she wants, when she wants, how she wants, and is taking perverse pleasure in doing so.” This new crop of young artists are aware of this ongoing problem of the male gaze, “but do not really give a damn. Instead, they assume different gazes and just make their work, no matter who is looking.”

Over the past two decades, the art world has begun to embrace artists like Mickalene Thomas, Catherine Opie, Collier Schorr, and Lola Flash. Yet despite recent progress, photographer and a civil rights litigator Renée Jacobs observes that queer women have never had their own Robert Mapplethorpe.

Visibility and representation have long been an integral part of Renée’s work. She got her start in the 1980s, working as a freelance photojournalist for The New York Times while still in college. At the age of 24, she published her first photography book, Slow Burn: A Photodocument of Centralia, Pennsylvania, a landmark work documenting one of the biggest manmade environmental disasters that had ever occurred.

After completing the book, Renée felt adrift and decided to pursue a career in environmental law. She received a scholarship to study at a top school for the subject and relocated to Portland, Oregon — only to switch to civil rights and Constitutional law during her final year. On graduating in 1990, Renée’s life shifted radically.

“I had a friend who had written a play about — wait for it — a lesbian softball team,” Renée says, still deeply closeted at the time. “The playwright’s girlfriend had written the musical numbers. I went to spend some time with them, promptly becoming completely enamoured with the first basewoman. Unbeknownst to me, the playwright had instructed the team that it was their duty to help me find my inner lesbian that weekend. Mission accomplished.”

After returning to Portland dazed, confused and in denial about her sexuality, Renée received a call from the playwright: her girlfriend had been fired from her teaching job after the principal saw flyers advertising the play bearing her name. Renée immediately agreed to take the case pro bono. “At that time, gay rights cases were few and far between, but I didn’t have to deal with the fact that there weren’t laws protecting gay employees because it was a straightforward First Amendment case,” she says. “It was as if someone had fired Tom Hanks for being in Philadelphia.“

Renée won the case and received an award from the American Civil Liberties Union — only to be fired from her job after being outed by the playwright in an alternative newspaper. “You can’t even imagine how homophobic people were back then,” she says. “They labelled it as ‘budget cuts’, but two of the three fired were gay,” she says. “That started me down a long, circuitous path of coming out, acting out, repression, confusion, feeling helpless and other-ed.”

Renée describes various encounters that reveal just how deeply ingrained homophobia was across professional circles. In 1995, she sued The Oregonian for refusing to publish same-sex wedding announcements, and lost the case. “I initially approached a lawyer who was a civil rights hero, asking him to take on the case, and he flat out told me, ‘No, I won’t do it. I don’t agree with that lifestyle,'” she says.

After returning to photography in 2008, Renée remembers a male mentor advising her never to reveal her sexual orientation or that of her models for fear that would impinge on the desire of male collectors. “He also told me to ‘tone down’ the sexuality and eroticism in my work, but that just pushed me to make more erotic work.”

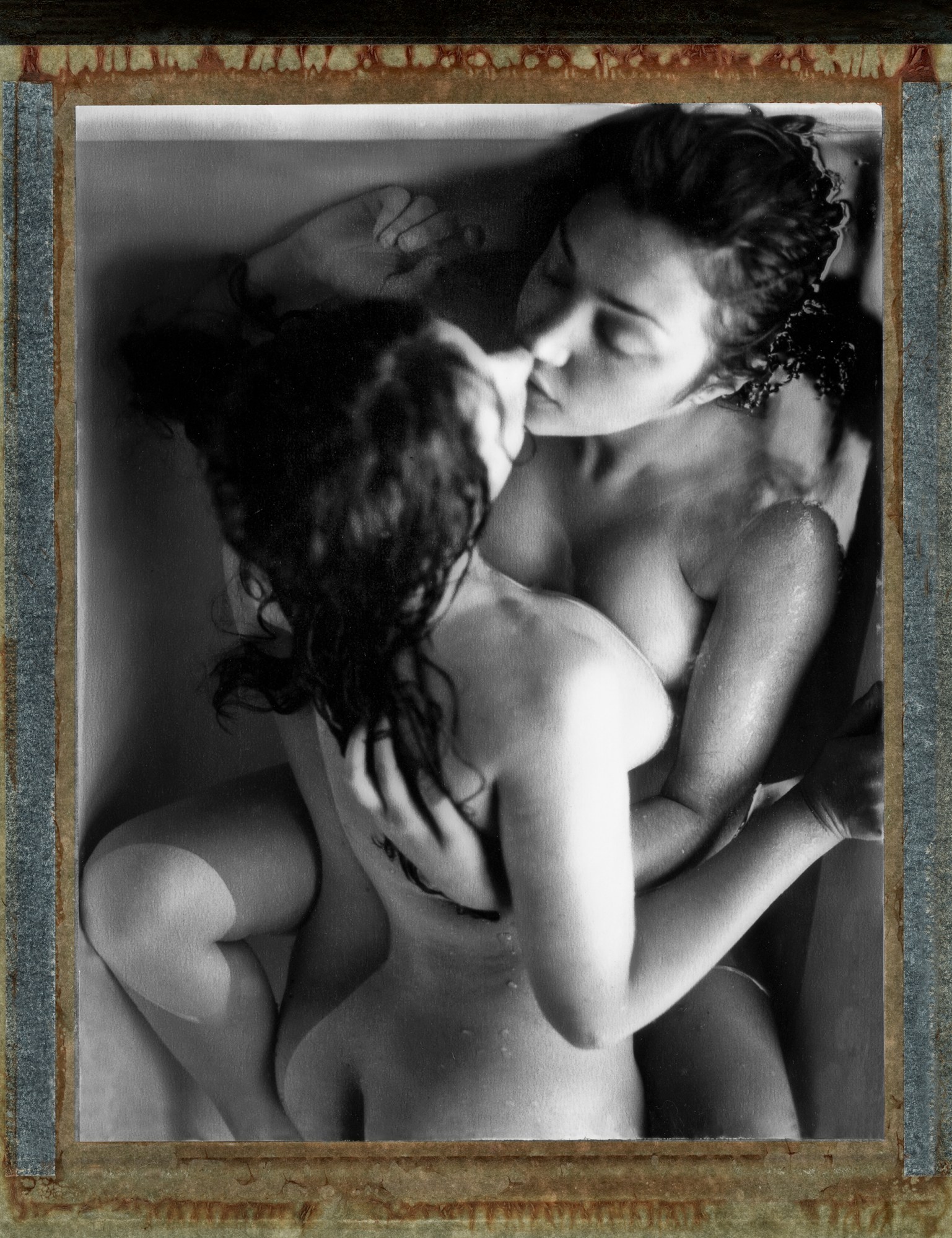

“I needed to make these photos for me. They were also photos the models wanted me to make as they explored their own sexual spectrums — and the infinite and powerful landscape of women’s desires made me understand and accept my own. All throughout my different careers, I’ve been told to stay in the closet. I firmly believe repression is the enemy, especially of women. Lesbian sexuality in particular is either erased or exploited, but rarely empowered.”

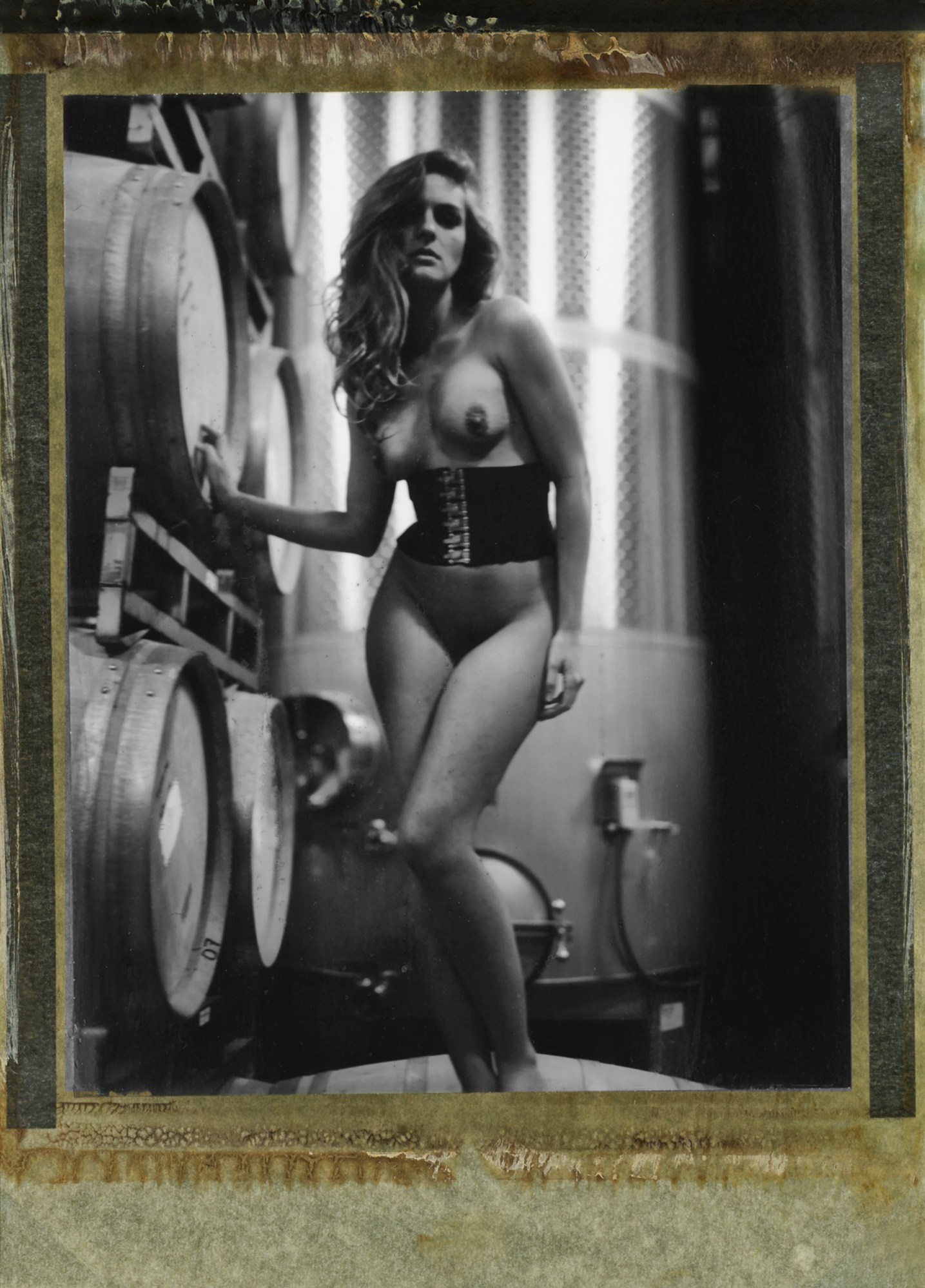

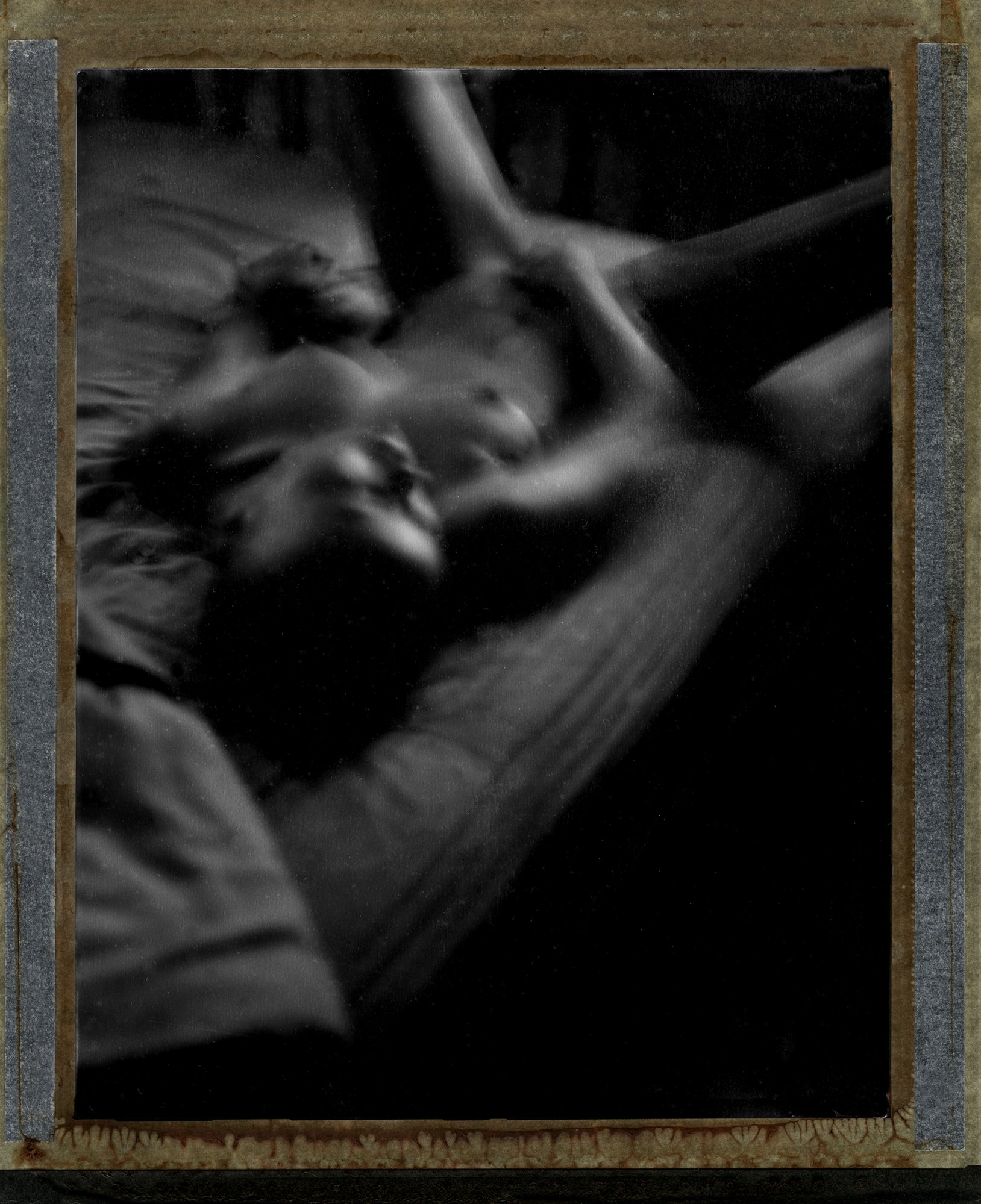

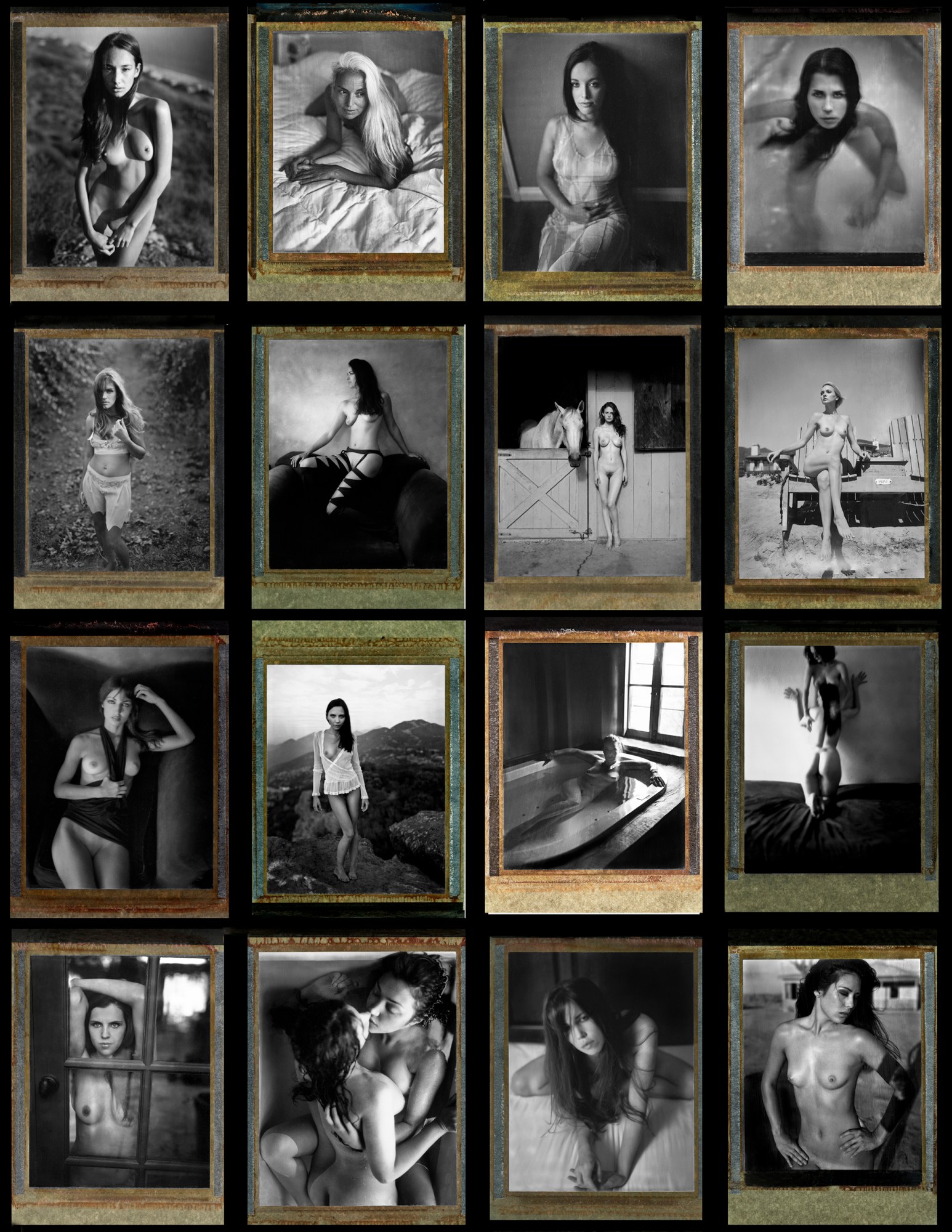

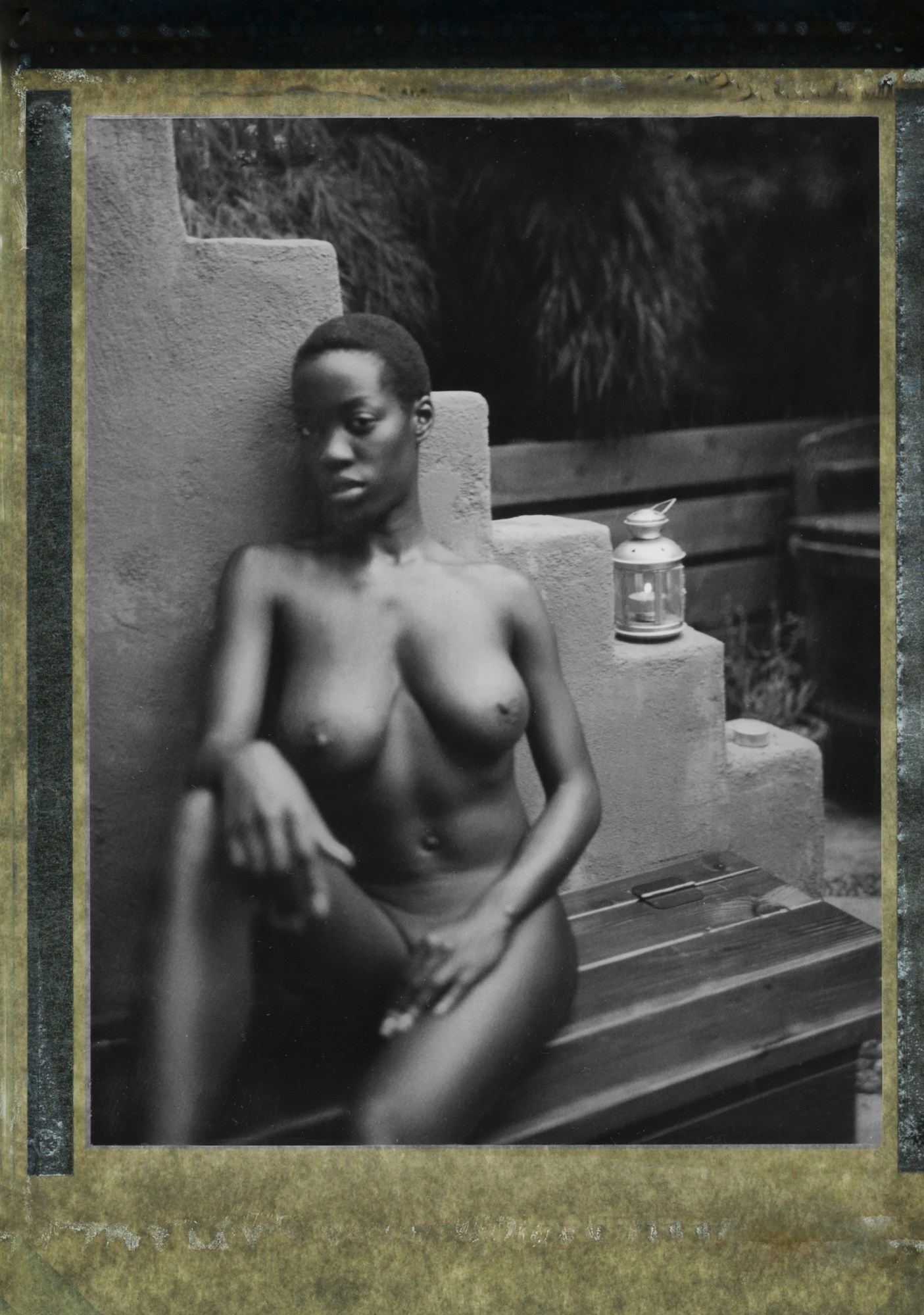

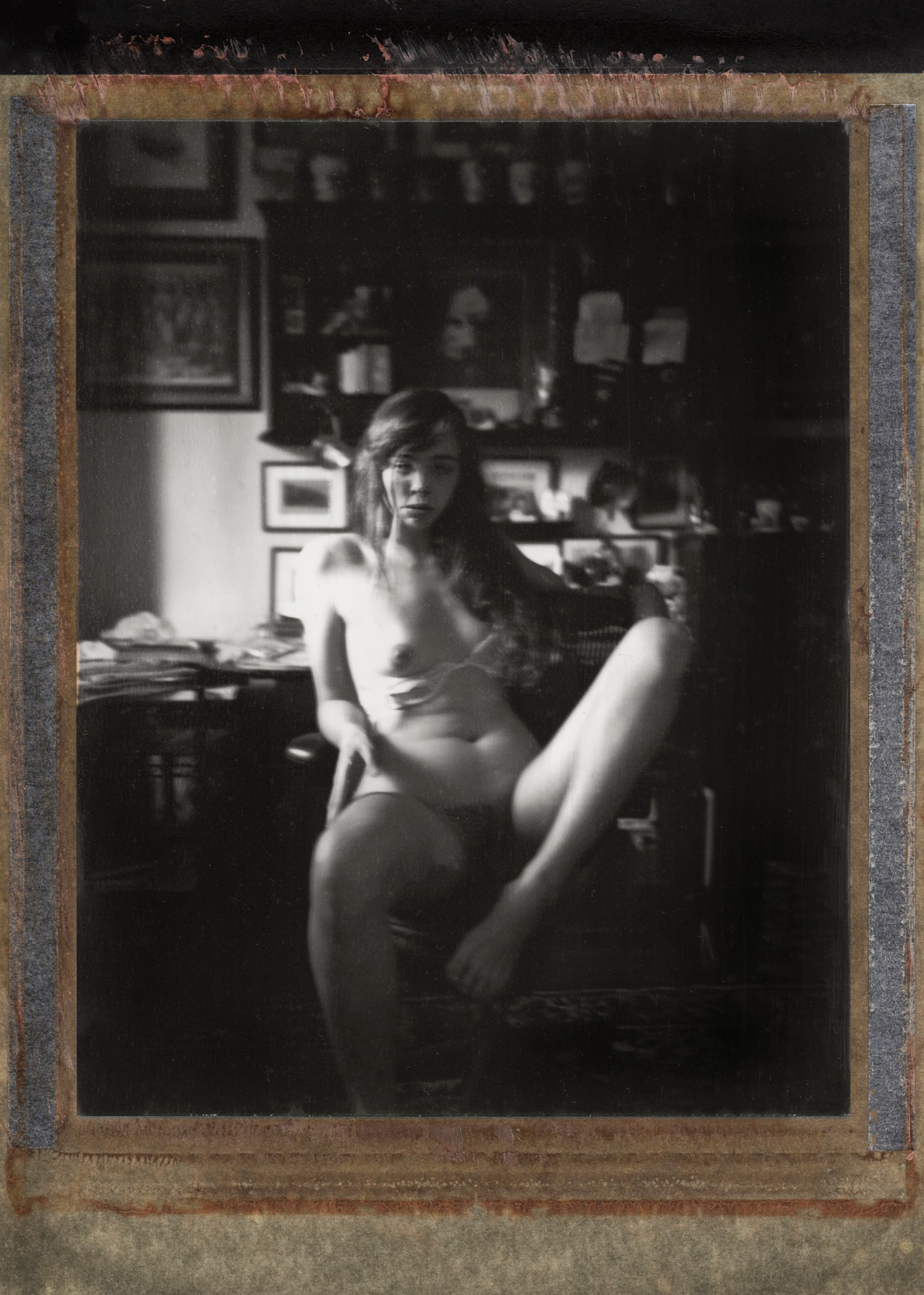

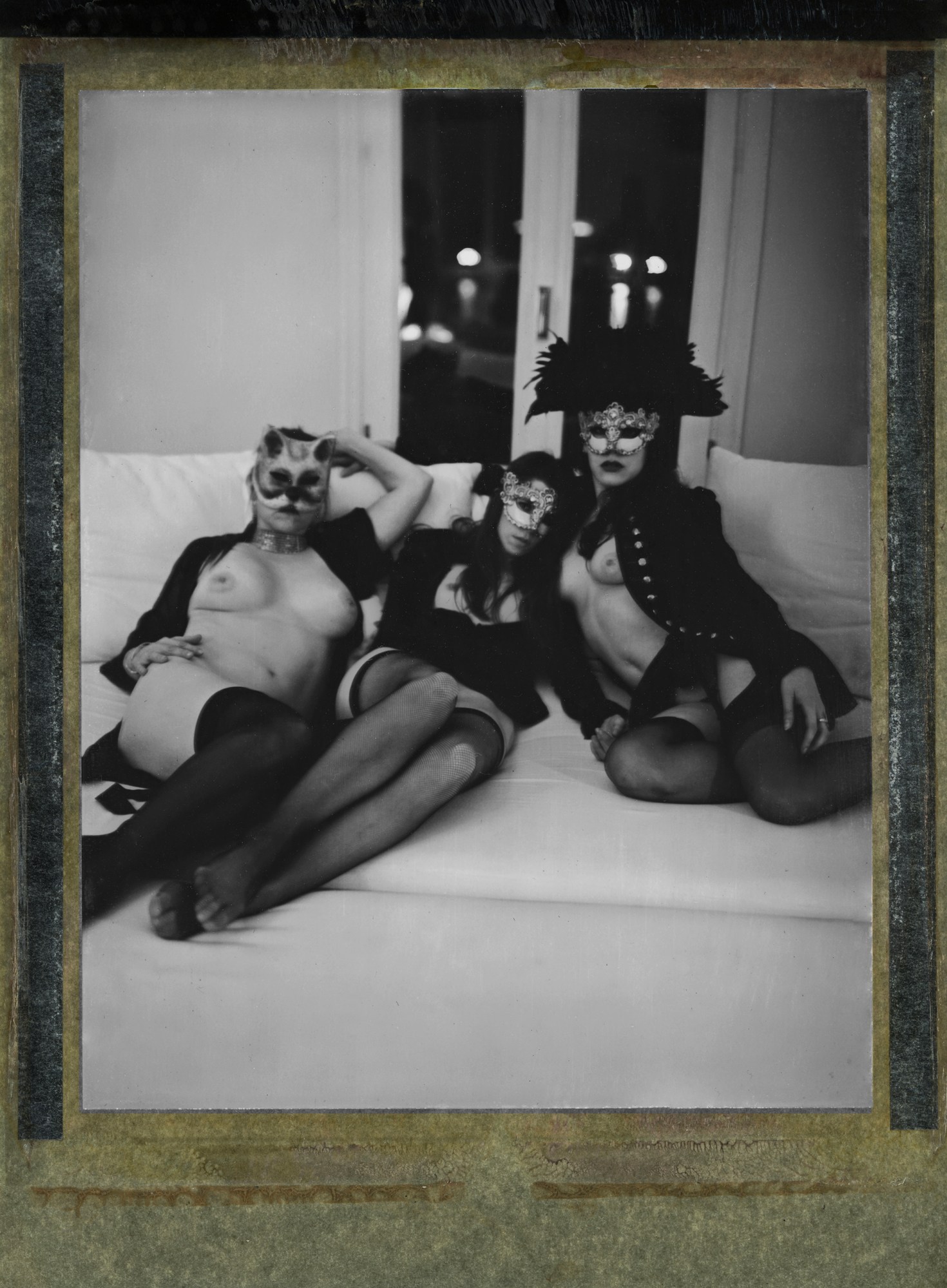

With the recent publication of Renée Jacobs: Polaroids (Galerie Edition Vevais) and an upcoming exhibition concurrent with Helmut Newton: Private Property, Renée brings forth some of her most erotic work to date. Inspired by the book and film, Paris Was a Woman, Renée creates images lost in time that evoke the work of queer artists Romaine Brooks and Berenice Abbott; writers Djuna Barnes, Colette, and Renée Vivien; the salons of Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas; and the bookshops of Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier.

Drawn to indoor photography in darkly lit rooms, Renée uses a Polaroid 110 camera converted for long-expired Type 55 film to create images filled with longing for things we can’t fully grasp or acknowledge. “The imperfections of the film are perfectly suited to reflect desires that are not always on the surface, longings sometimes seen and felt only on the peripheries of our consciousness,” Renée says. “Using this method for this body of work was a perfect way to engage my subjects in a more languorous, timeless type of reflection on female sexuality.”

For Renée, lesbian erotica made by women is long overdue. “I saw a well-respected gallerist in Europe do a show of nudes by women recently, and she spoke at length about how great it was do this because it desexualised the female nude,” she says. “Why is that the goal? No one told male photographers they could only shoot nudes one way. They are allowed to do the spectrum from Edward Weston to Araki.”

Much has changed since Renée saw anti-pornography feminists Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon speak while she was in law school. “I thought they were absolutely right, that pornography is exploitation,” she says. “It’s a large part of why I never wanted to shoot nudes. Then I realised how much beauty they could bring into my life. I never thought they would take a more erotic bend but it became so empowering. I think we’re just at the beginning of breaking this wide open. I sure hope we are.”

‘Renée Jacobs: seeingWOMEN‘ is on view at Fotonostrum Mediterranean House of Photography in Barcelona from 19 May-24 July 2022.

Credits

All images courtesy the artist