Growing up in a lively Dominican household in Queens, New York with at least five cousins, two aunts, his grandmother and great grandmother; Frankie Perez needed an escape. So when his neighbour came by one afternoon excited about some light b-boying moves he’d learned from a cousin on Long Island, the 13-year-old got hooked on a dance form that’s all about freedom, persistence and creativity. Frankie soon joined the breakdancing ecosystem in the city, training and competing at cyphers and jams. “It kind of blew my mind,” he says, “breaking in New York during a certain time was like living in a movie.”

By the early 2000s, Frankie had joined the second wave of the b-boy crew Supreme Beings — a collective of almost 20 dancers — and quickly made a name for himself in the scene. “I have vivid memories of practising in a dead end street in Corona, Queens in the summertime, where we started off in the afternoon and went to the end of night freestyle rapping with each other and breaking, then going to the corner bodega to eat and talk.”

Weekends were spent travelling uptown to Washington Heights and the Bronx — where the dance first came to be in the 70s. It all started back when DJ Kool Herc began isolating and looping instrumental sections of records that emphasised a heavy drum beat, creating ‘breaks’. Known as the Father of hip-hop, he left space for MCs, rappers, beatboxers and breakdancers to perform.

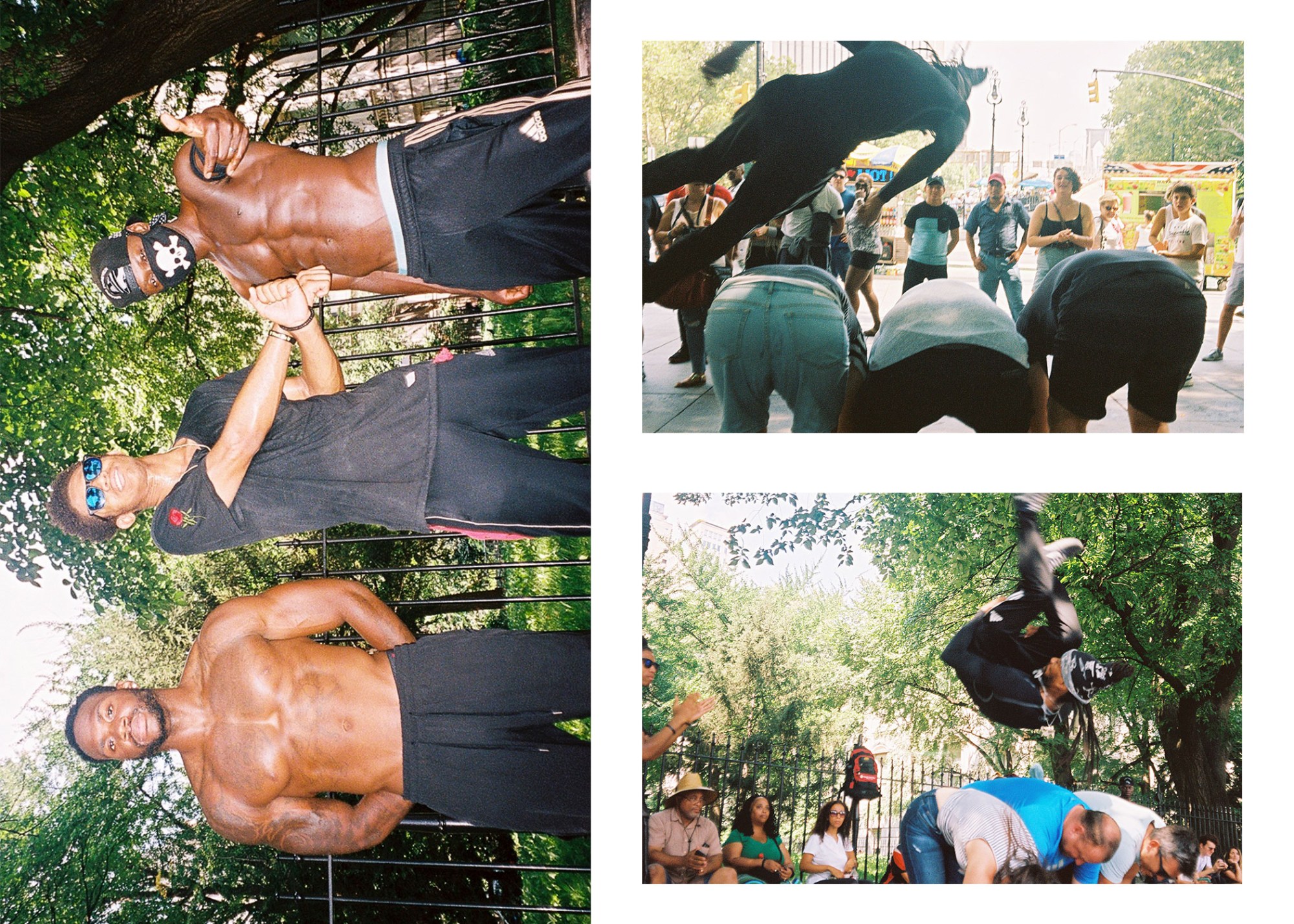

Across New York, Frankie competed with dancers he respected in displays of physicality and inventiveness. This even included a concrete battle against b-boy pioneer Richard “Crazy Legs” Colon of the Rock Steady Crew, a Puerto Rican-American whose blend of dancing, acrobatics and martial arts were some of the first to be recognised by mainstream press. Crazy Legs had gained prominence in the 80s, both in New York and abroad, with roles in the movies Flashdance, Wild Style and Beat Street. “He embarrassed me a little bit because I had knee pads on and he stopped the music and made me take off my knee pads in front of everybody before continuing the battle,” Frankie says. “He’s old school and he doesn’t wear any pads.” Luckily, the new kid on the block won the dance battle after three audience-judged rounds.

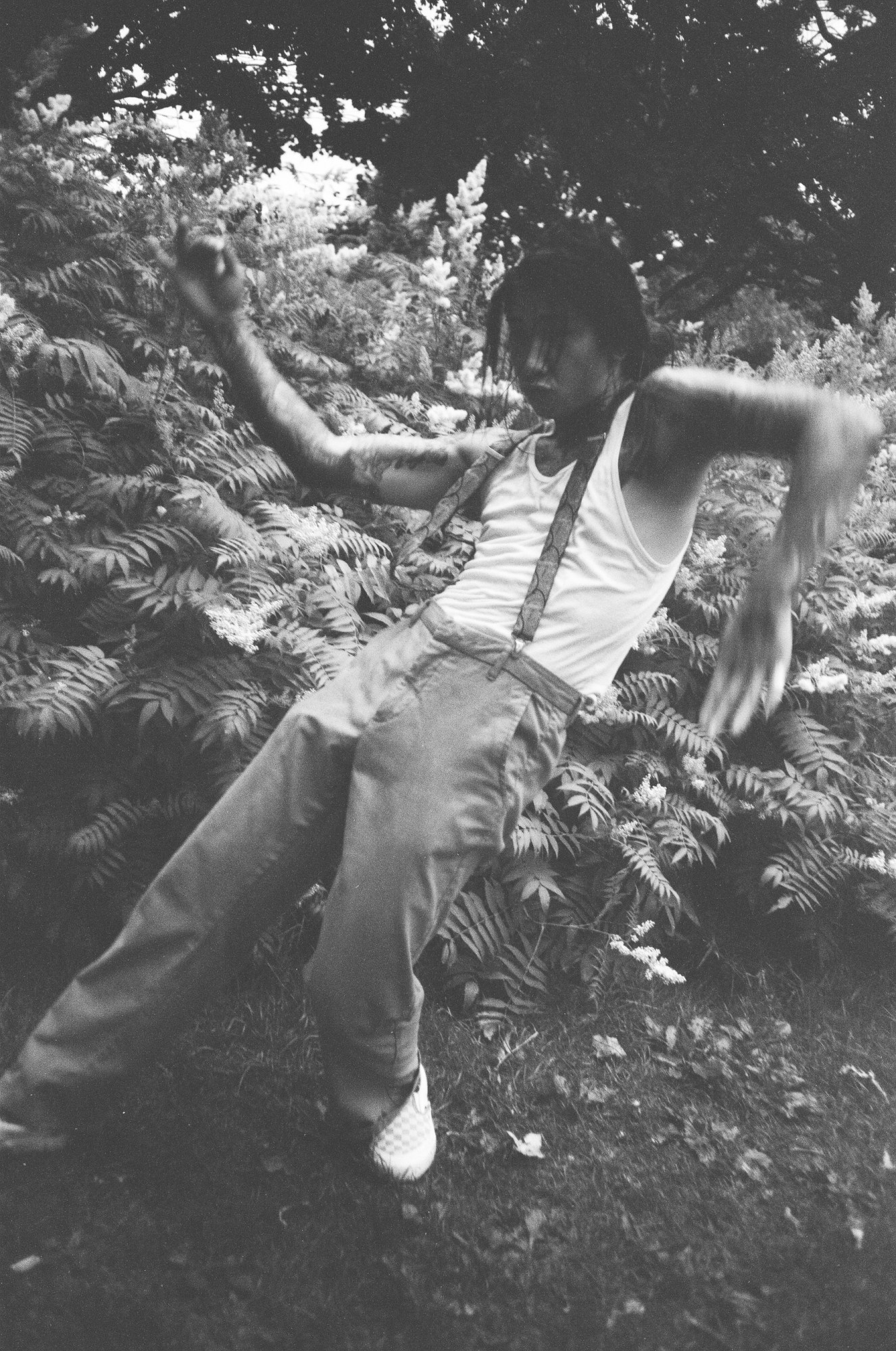

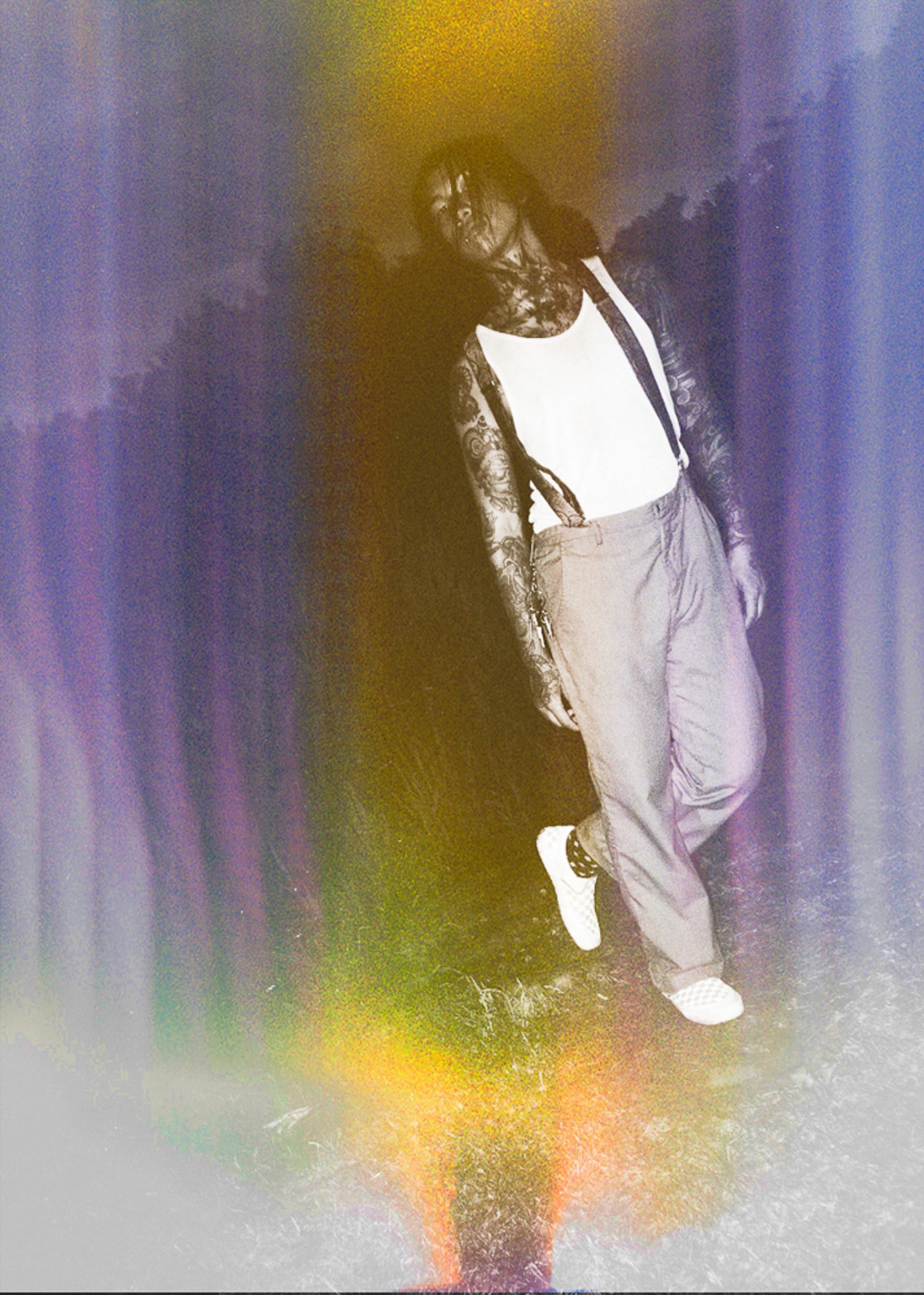

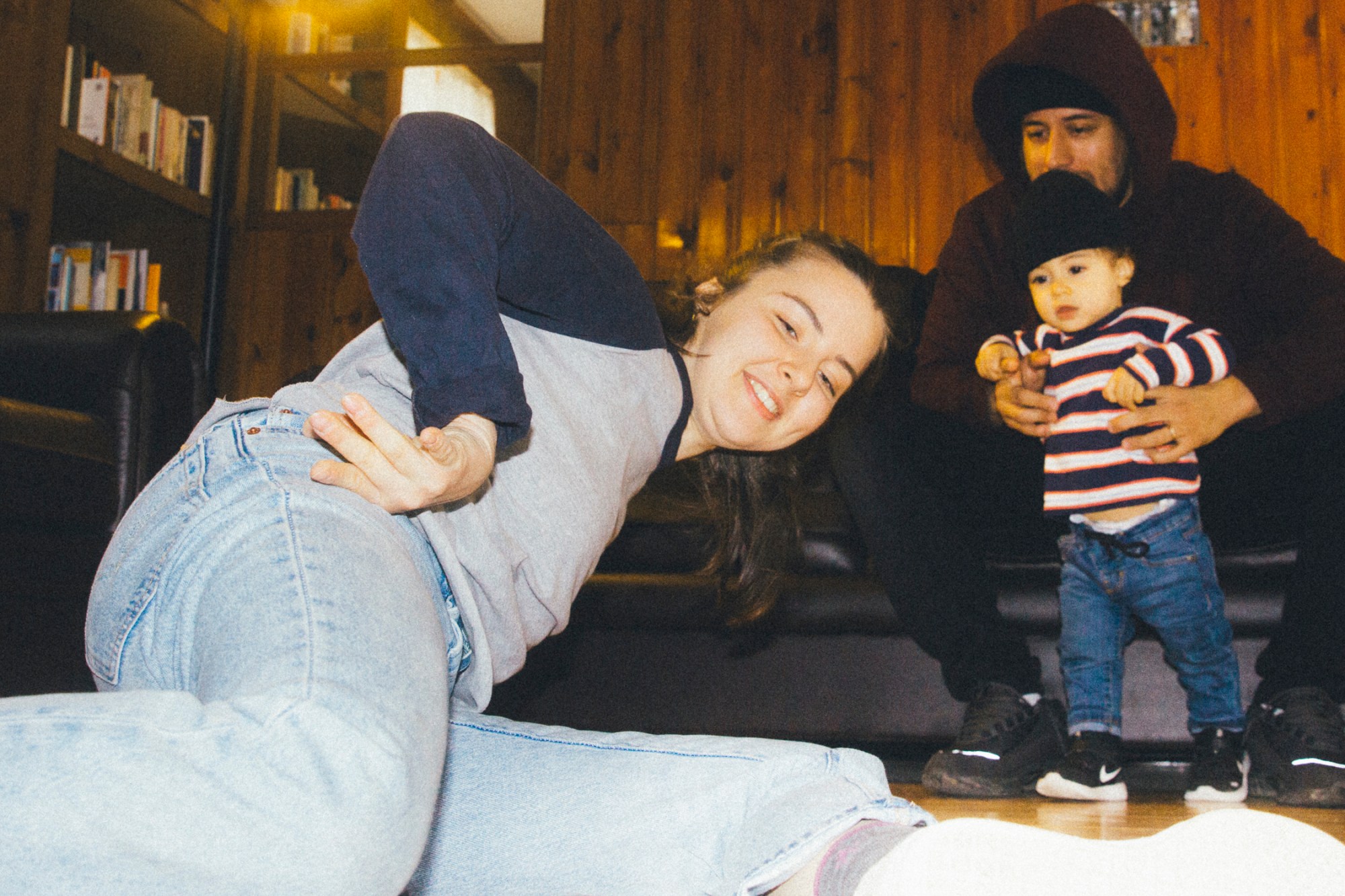

It’s events like these that Frankie captures in a series of high-octane documentary and fashion style portraits in his new self-published photo book See Me Up? It’s ‘Cause I’ve been down. But he turns his lens on the raw energy of cyphers, parties and training sessions in auditoriums, community centres and schools too. Taken between New York and Montreal — where the 31-year-old lives with his wife and newborn baby — as well as in Boston, Texas, Florida and Mexico City, the vibrant and dynamic lo-fi snapshots capture contemporary b-boy culture around the world.

B-boys and b-girls are documented practicing in concrete yards, dusty pitches and wet parks; immortalised in their poses at the perfect moment, by someone who knows all the moves. At cyphers or street jams, dancers “exchange [their] art with each other,” Frankie says. The physical version of rap’s taunt and boast, it’s where they show what they’ve got and build a reputation. Frankie also tried to capture aspects of breaking that are often overlooked in traditional hip-hop imagery, like street hitting. Buskers who perform on the street, Frankie says, form a subculture all on their own. Their dance style is tailored towards an audience, so they’ll have more explosive, flashy moves that have their own little intricacies and can certainly rival somebody who, like Frankie, came up in the competition world.

Frankie started taking pictures because he didn’t want to rely on others to promote his own dancing, but soon fell in love with the freedom of photography. “It reminded me a lot of breaking and creating moves,” he says. Frankie hopes the book can be an authentic frame of reference for people outside of the scene, given portrayals of breaking in media often involve dancers doing moves that are overly-stereotypical of the style.

He also hopes it will set a new standard of what success looks like among breakdancers, who are currently unable to survive on just dance alone. Aside from teaching or winning competitions, there are no real paid opportunities for b-boys and b-girls. Being a backup dancer for a musician on tour is about as good as it gets, Frankie points out, but even that remains secondary. “I want the highest level of success for us to be higher than that,” he adds. Since breakdancing was recently announced as an official sport in the 2024 Olympics, Frankie hopes dancers will soon gain prestige and corporate endorsements like that of other Olympians.

B-boying is more than just dancing to Frankie, who hopes to qualify for the upcoming Olympics and continues to use dance as a coping mechanism — a source of relief and strength to help him navigate the many challenges of life. “When I got kicked out of high school, for example, I didn’t go straight home, I went straight to practice,” he says. Frankie’s favourite photograph from the book is the cover image of one of the members of his crew breaking on his back, wearing a blue tracksuit with red shoes. It’s visually striking and captures his friend at the moment he overcame a difficult period in his life, when he finally returned to the scene after a hiatus.

“I’d like to advocate for and see other people taking what they’ve learned from the dance scene and applying it to other things in life as well,” Frankie says of the discipline, persistence and pride intrinsic to the sport. “Whether it’s trying to finish school or get a job in some other type of industry, if you’re able to teach yourself to spin on your head… if you can do that, other things are possible.”

Frankie Perez’s ‘See Me Up? It’s ‘Cause I’ve been down,’ can be purchased at Pomp Media.