The world cracked open for Maripol the first time she held a Polaroid camera in her hand. Her boyfriend at the time, Edo Bertoglio, the Swiss photographer behind iconic New York documentary Downtown 81, gifted the French creative an SX-70 at a time when Manhattan was alive and buzzing with energy, parties and the filthy disco glamour that has come to define the 80s.

“It was like magic,” Maripol tells i-D over the phone from her studio on the outskirts of Paris. “I had been to a Beaux-Arts school and studied portraits. My friend from Paris went to the factory and gave me portraits of Andy Warhol, and I love Andy. He was very nice, not pretentious at all.”

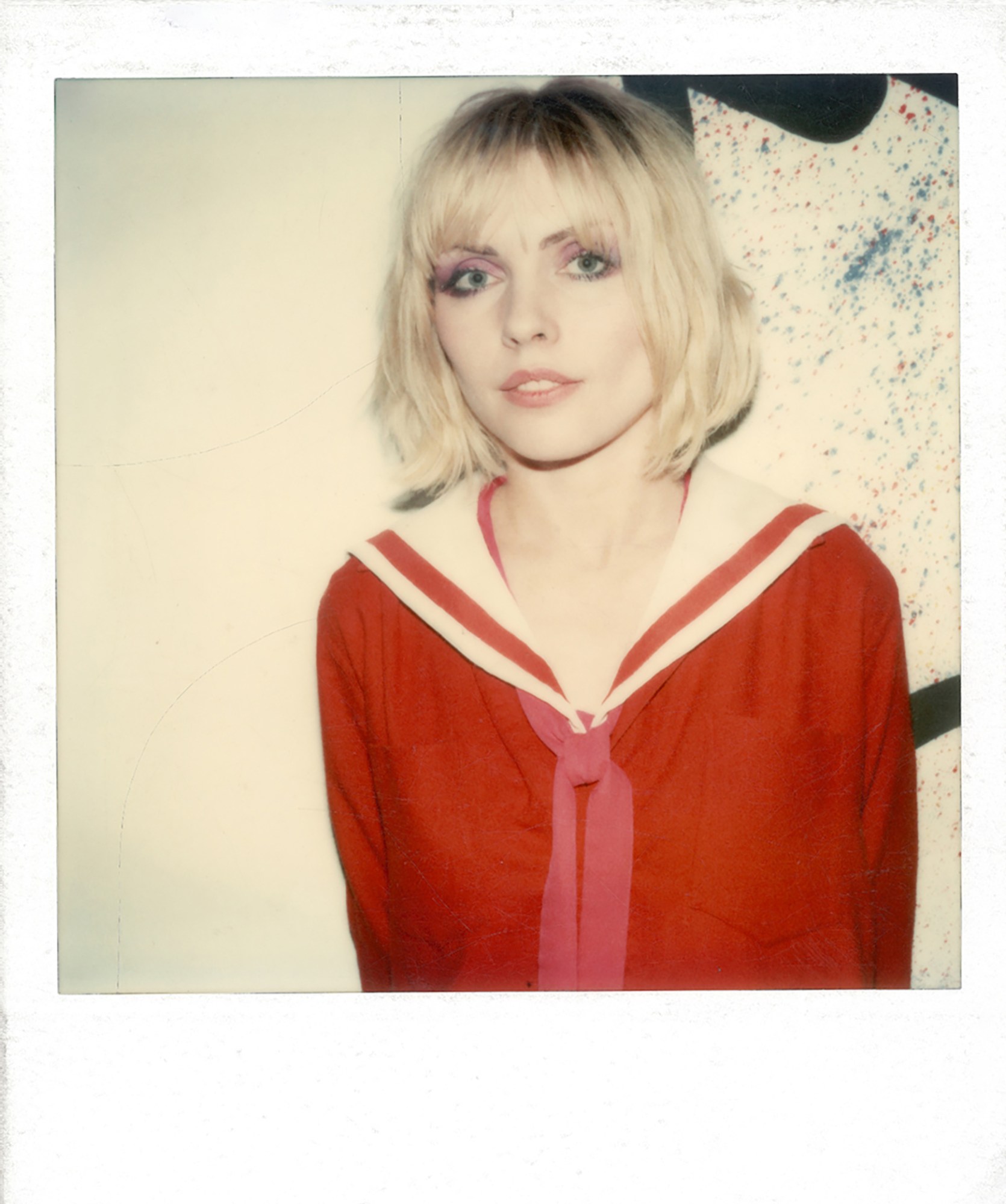

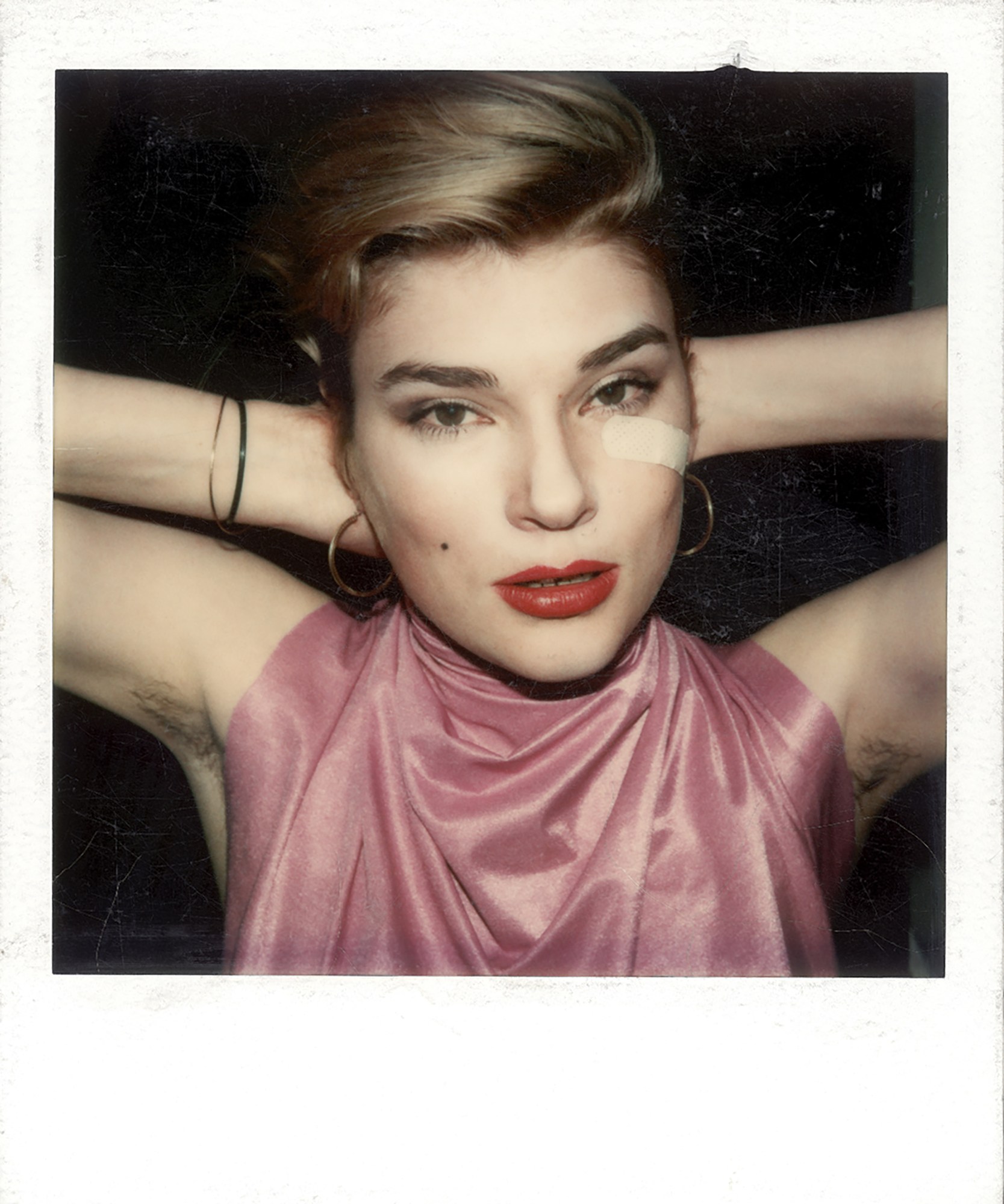

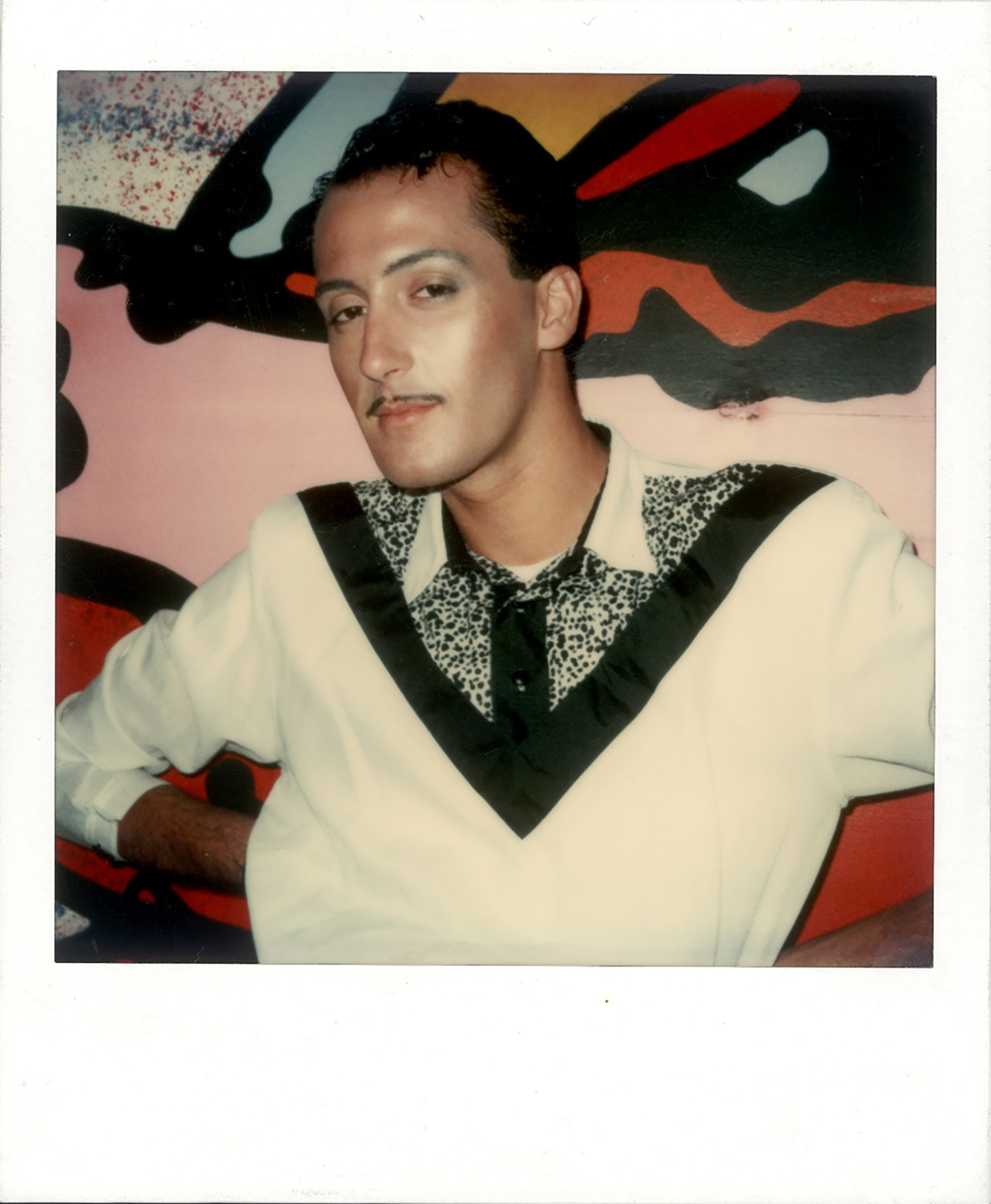

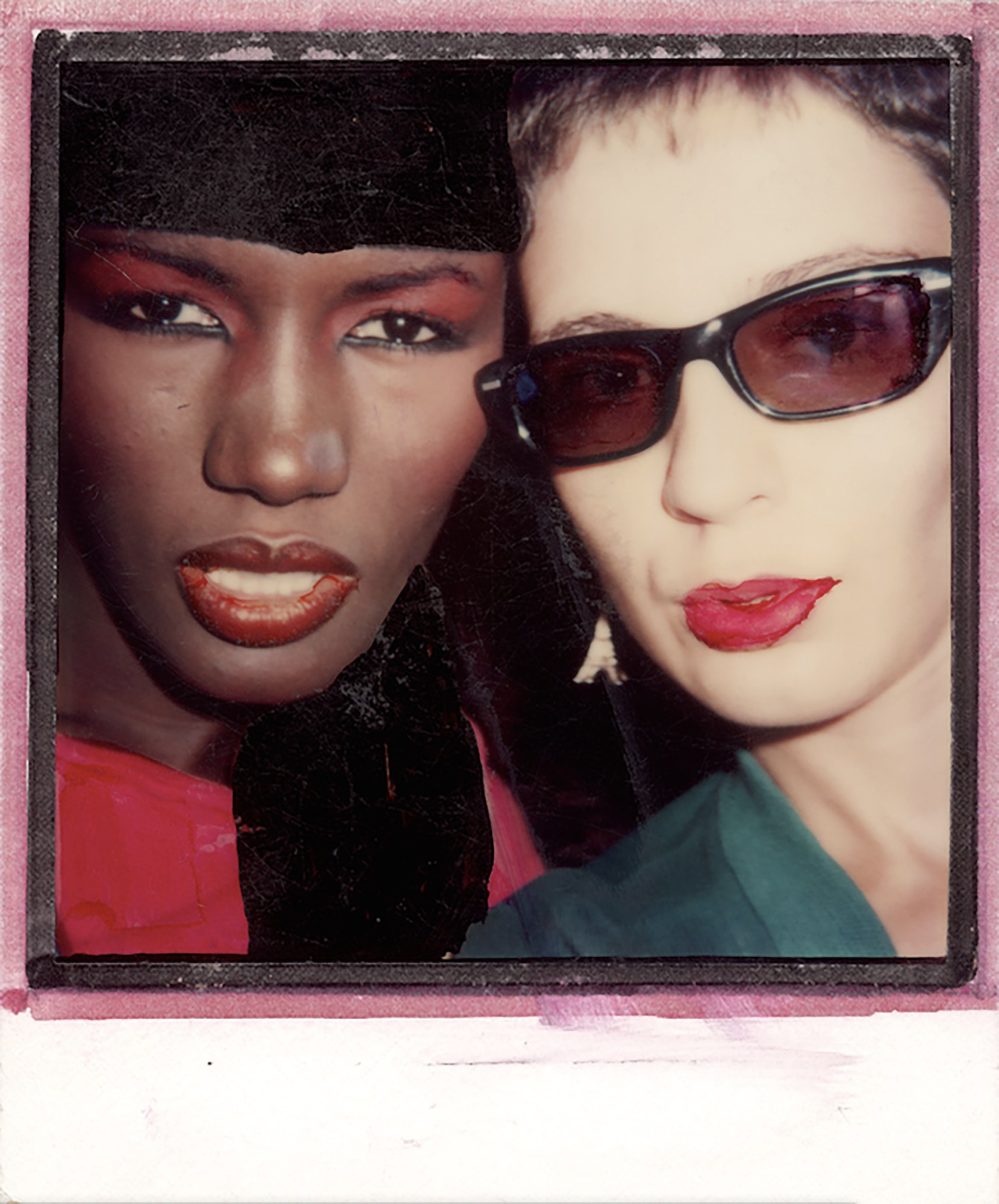

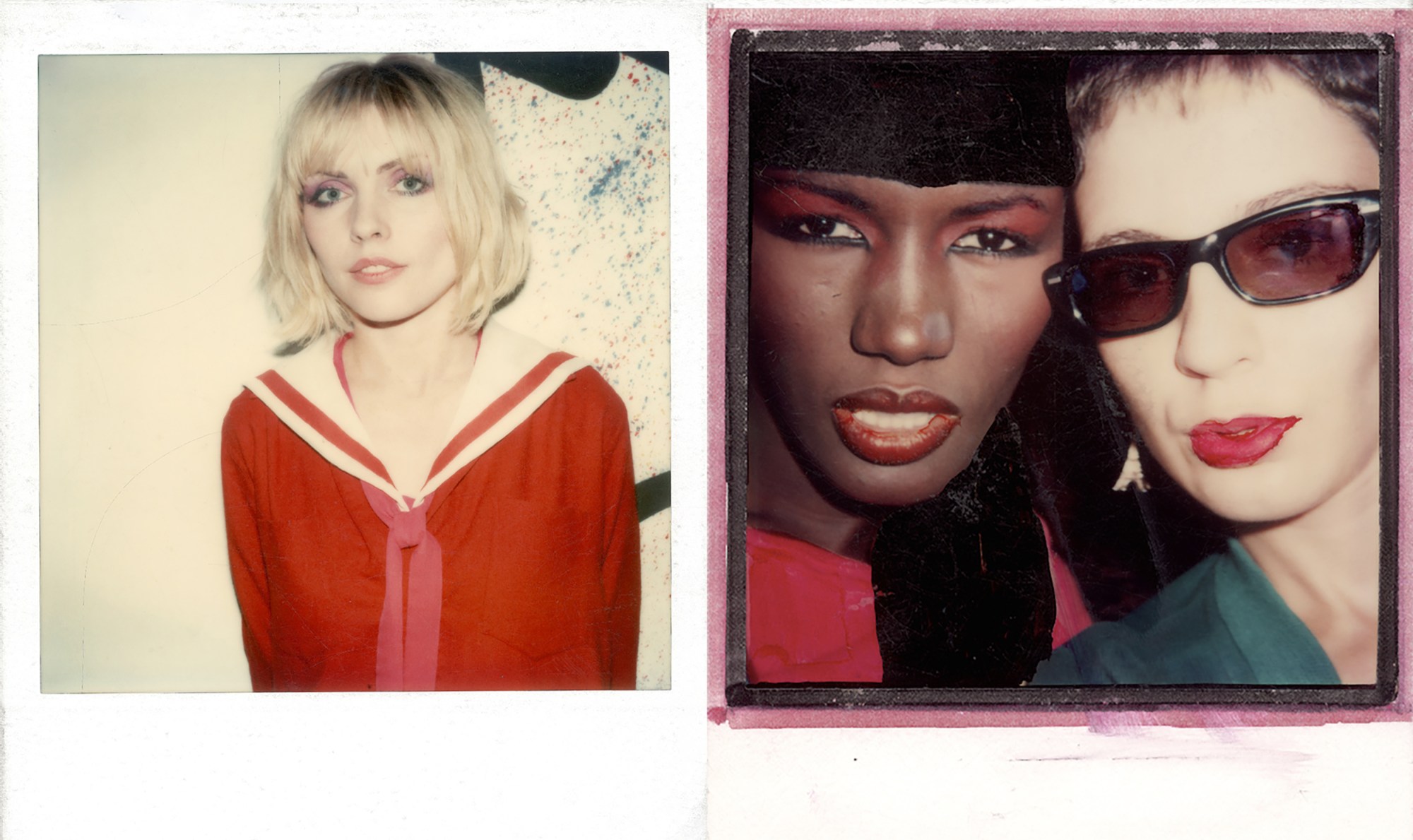

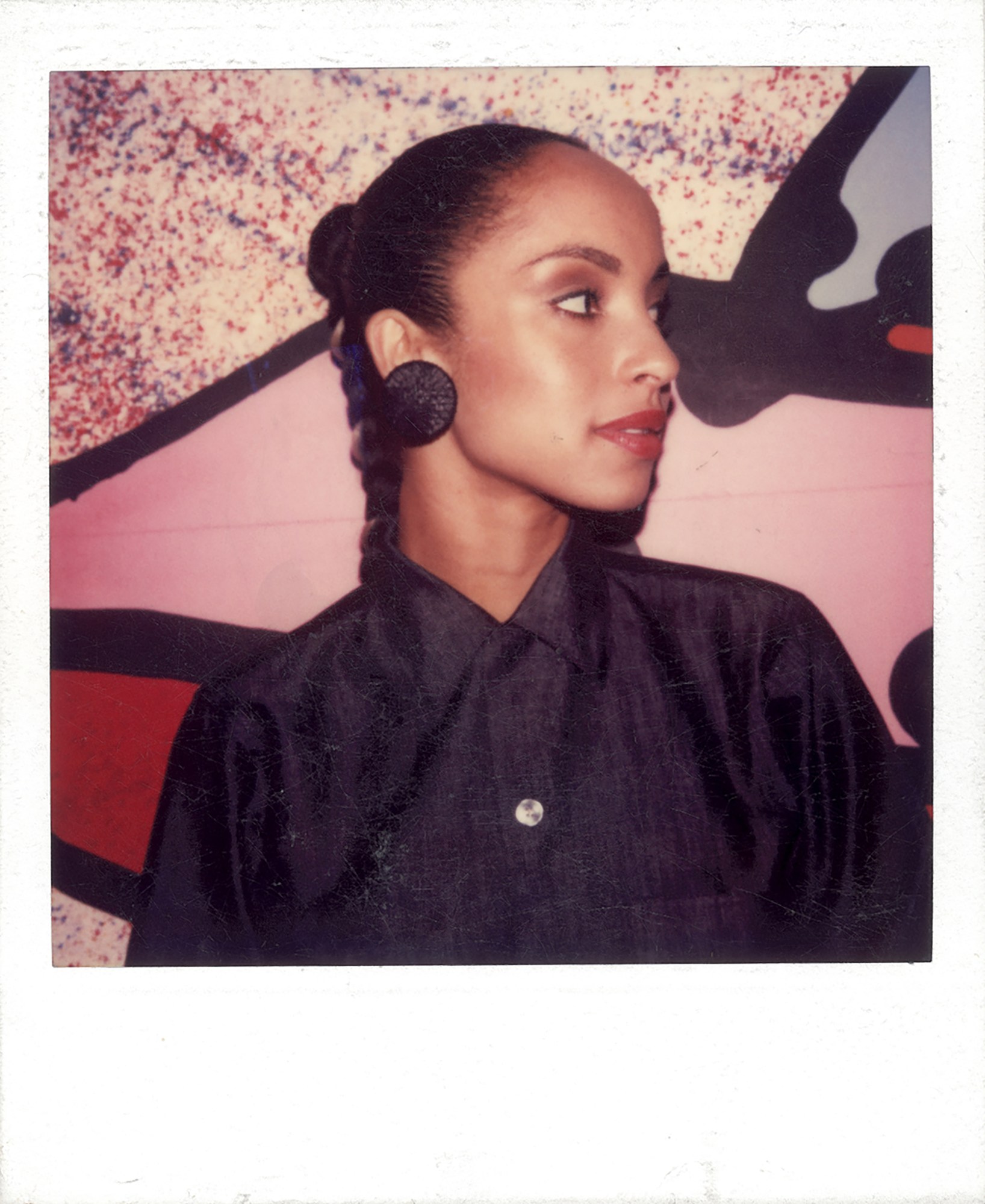

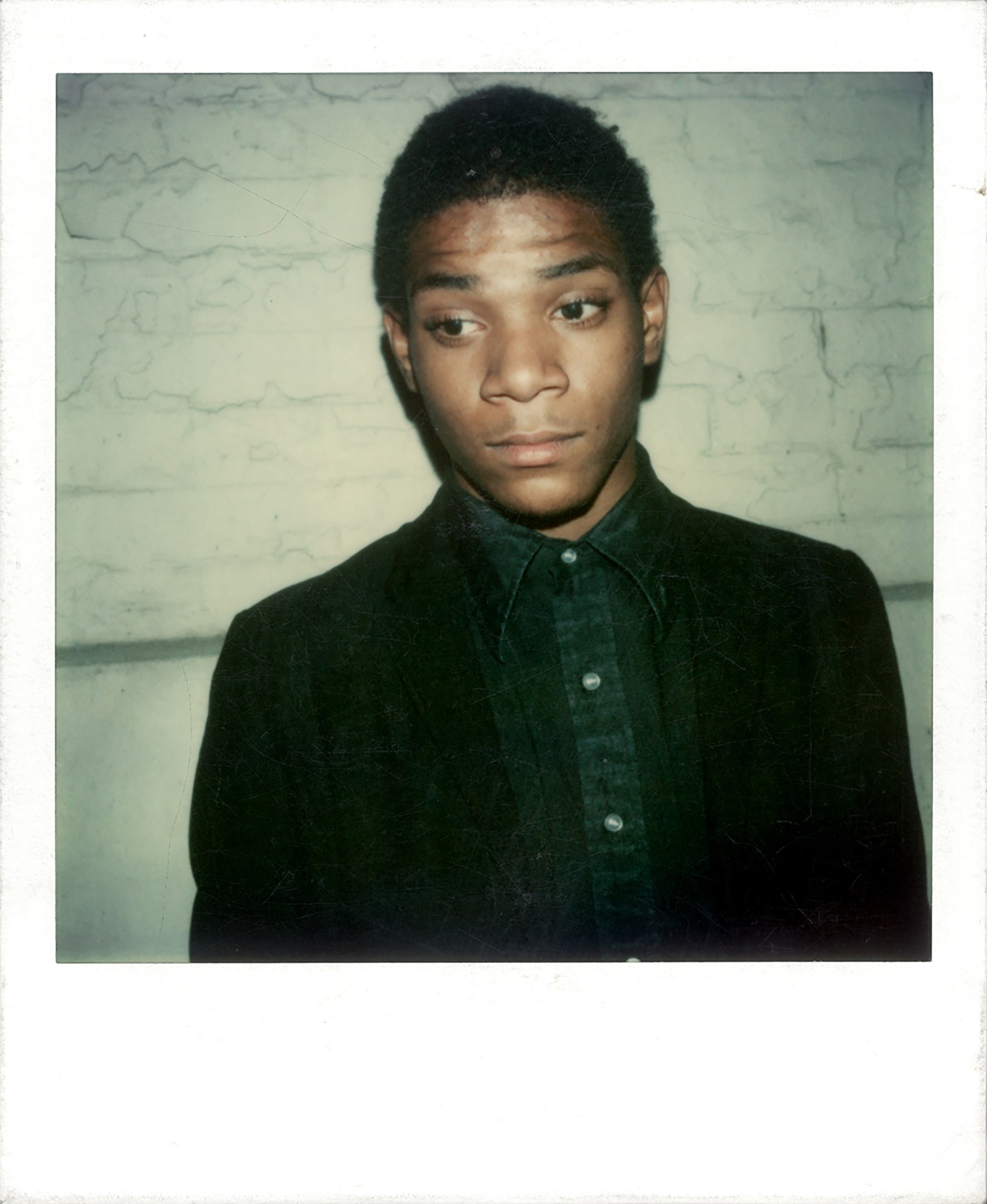

Warhol wasn’t the only legendary figure of Manhattan’s hey-day that Maripol hung around. Her sprawling collection of portraits spans every corner of New York’s cultural sphere at the time, with everyone from Blondie’s Debbie Harry to Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat posing for her. Eager to capture it all and with her finger on the pulse of the underground, at ease with the punks and the Studio 54 crowd, as well as the burgeoning fashion world as Fiorucci’s art director, Maripol set out into the night again and again.

Thousands of Polaroids later, the multi-hyphenate has garnered a reputation in the fashion world and two key nicknames: “the gate-keeper of 80s club culture” and “Queen of Polaroids.” The cultural icon’s eye hasn’t waned either, she recently photographed Dior’s autumn/winter 20 collection on Polaroid, a marathon four-day shoot with 150 looks that resulted in 700 chic portraits. “We decided Polaroid gives [the images] a lot of soul,” she says of her process. “With digital a lot of things are formatted the same and it’s — excuse me — boring!”

Here Maripol tells us about her iconic portraits, capturing New York’s golden age and staying analog in a virtual world.

Who was the first person that you photographed?

I wouldn’t know that! [Laughs]. I do like the pictures of Studio 54 that I took. I took a selfie at that time with Bianca Jagger and my friend Edwidge, who came to visit us in New York. We were in the back. My boyfriend took a photo of me taking the picture, but when you see the result it’s only a photo of me with the forearms of the face of each girl. I wasn’t good yet.

The images all have a very intimate quality to them! You have photos from people throughout the entire spectrum of 80s NYC nightlife, from the punks to the Studio 54 crowd. When did you start carrying the camera around?

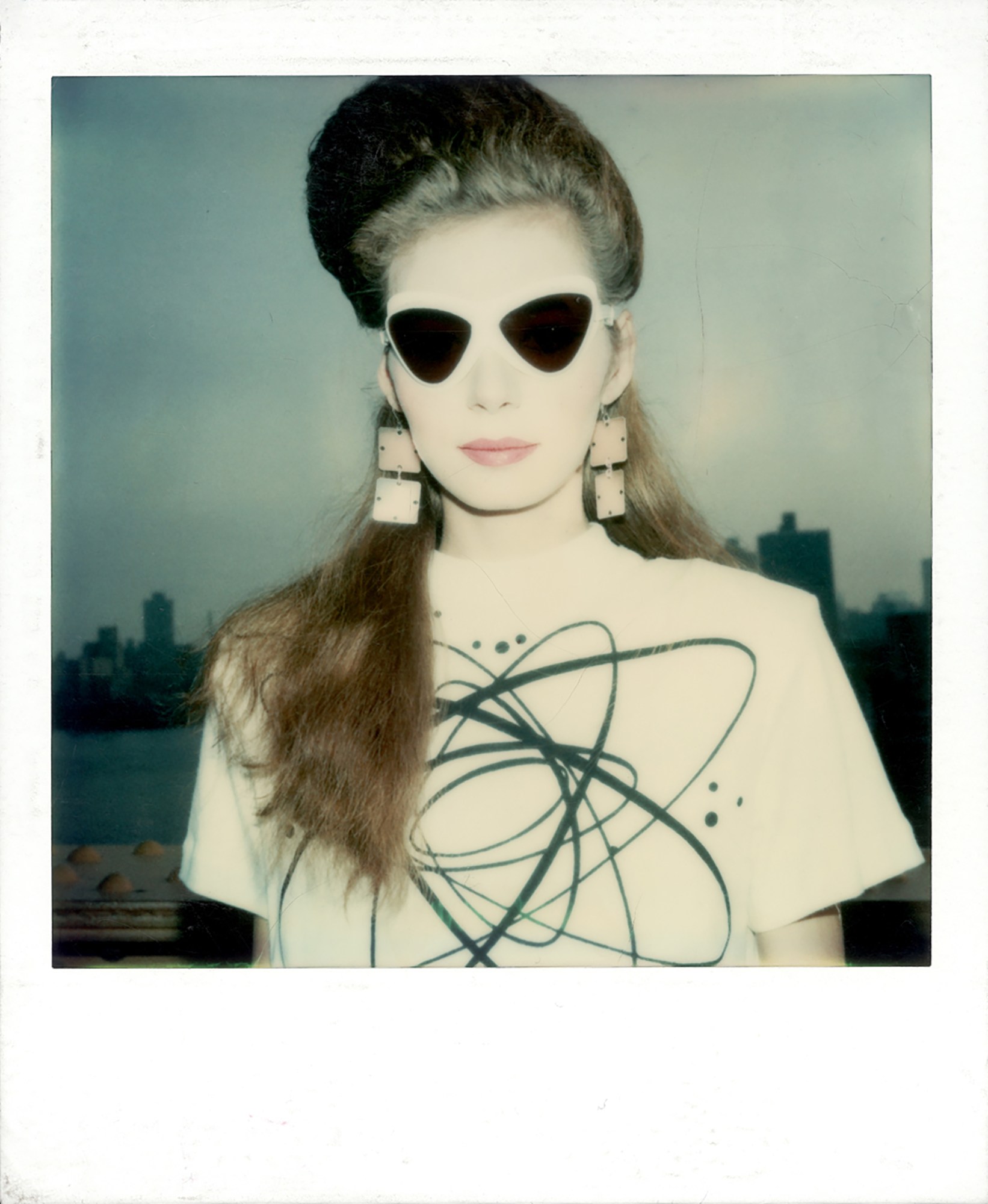

New York then was great waves of people coming. People would go to the clubs. It was a run-down free-for-all. I was working for Fiorucci and I was doing a lot of fashion myself. The camera was my tool. We didn’t have cellphones or the Internet, but we knew where the party was going to be that night, where the opening of the gallery was. The scene was very small. We did have landline telephones and people would design the invitation and you’d receive it in the mail if you happened to be on “the good list.” If you wanted to talk to someone, it was easy. It was easy to meet people. The club became our living room of the night, and the day at home was becoming the night. Sometimes we were up until 7 AM, and it would be summer and very hot and we’d find a pool or a park in New York that you’re not allowed to go to, but you go.

Can you tell me a story you remember of a notable night out with your camera?

I only took photos at night! A lot of time we did parties in my loft, like the one [where I took the portrait] of Debbie Harry in 1979 or 1980 in my loft on Bleecker and Broadway. My wall had hundreds of Polaroids on canvas that captured the New York community of the time.

How did your experience as a photographer help you when you became the art director of Fiorucci and as a celebrity stylist for icons like Madonna? How did fashion and photography go hand-in-hand for you?

When I was at the Beaux-Art [school in Paris], you have to learn how to draw, you have to learn how to take pictures. At the same time, I went to a technical school, so I was doing my own clothes after the age of 15. I think it’s something you have or you don’t. I grew up and always had these teenage magazines. I was in love with Cher and her husband, the videos. Before that, we had Motown — those were the queens of fashion. There was always influence from the previous generation, the movies of 40s and 50s. The fashion was amazing, the Hollywood fashion. Chanel opened up the way women dressed by using the corset. There’s always something going on that inspires a new generation. In my case, it was English music coming to New York.

How do you see the fashion dichotomy between New York and Paris?

Now or then?

Both!

Let’s go back to the 70s — have you ever seen Gucci clothes? Gucci under Alessandro Michele takes a lot of examples from the past. Who could have thought the clothes they were making would reach women on Madison Avenue? You think we did? We did not! It’s a mix of things you make yourself and from the old style. People also travel and grow their fashion. When I was young I used to go to London, so my influence would come from King’s Road. There was [Malcolm] McLaren and Vivienne Westwood — so cool. But you’d go to Biba… I think that’s why I went to America. That’s where I got a lot of my influence. You know, [who] one of the biggest influences on fashion was? David Bowie! He invented glam rock, and before him there were others, even Elton John… musicians! Like I said before, the generation before paves the way.

Are there any contemporary icons you would point to that are shifting the cultural landscape?

I worked with Maria Grazia [Chiuri, creative director of Dior], the first woman to design for a major couture house in Paris. She’s a feminist, and I think she modernized and revitalized fashion.

Despite the predominance of digital, you’re seeing a big resurgence of film photographers. What advice would you give to analog artists working in our virtual moment?

I think it’s really great to have something you can touch. I take iPhone pictures, but they get lost. At least with a Polaroid, you have something that stays forever. It’s an object. With Polaroid it’s also really fun because you can use a different edge. For Dior, I shot [the collection] in black edge, colored contour, metallic contour… kids are going back to that. I come from an analog family, everybody in my family took pictures all their lives—my uncle, my dad, my grandfather in the First World War. It’s a tradition for me. It’s easy to become lazy and only take pictures with your iPhone, but what the heck, man! It’s only convenient for Instagram or Facebook. There’s a documentary out about the Impossible Project, right before the revival of Polaroid. There was a point where I thought I would have to quit because you couldn’t find the film, but now I’m so happy that everyone is back on to film production, new film, new cameras. It took a few days to scan my edges, but I had very little “rejects”. I call them rejects because I forget to put on the flash or it’s my fault. Even if you have damage in film, people love damage on Polaroid film. Sometimes I draw on them and accentuate that damage.

How would you describe the 80s New York City era that you captured with your Polaroids three words?

“No Man’s Land!” The streets belonged to everybody. Roaming the streets of New York then was our past time; we were biking and walking instead of taking the subway. It belonged to everybody, places like LA, New York, Paris, Madrid… it’s such a mix of everything, of everybody from all over the world. A no-man’s land, I’m telling you. We were the new wave in a land that we made ours, that belonged to us.