It’s often in trying times that people turn to spirituality — times like these, for example. But while religion may serve as a temporary recourse for some, it’s a life-long guiding light for many others. Debatable as its relevance to contemporary life may be, it’s hard to argue against the impact it’s had on our cultural landscape, with artists all along history’s course channelling divine inspiration to produce truly awe-inducing work.

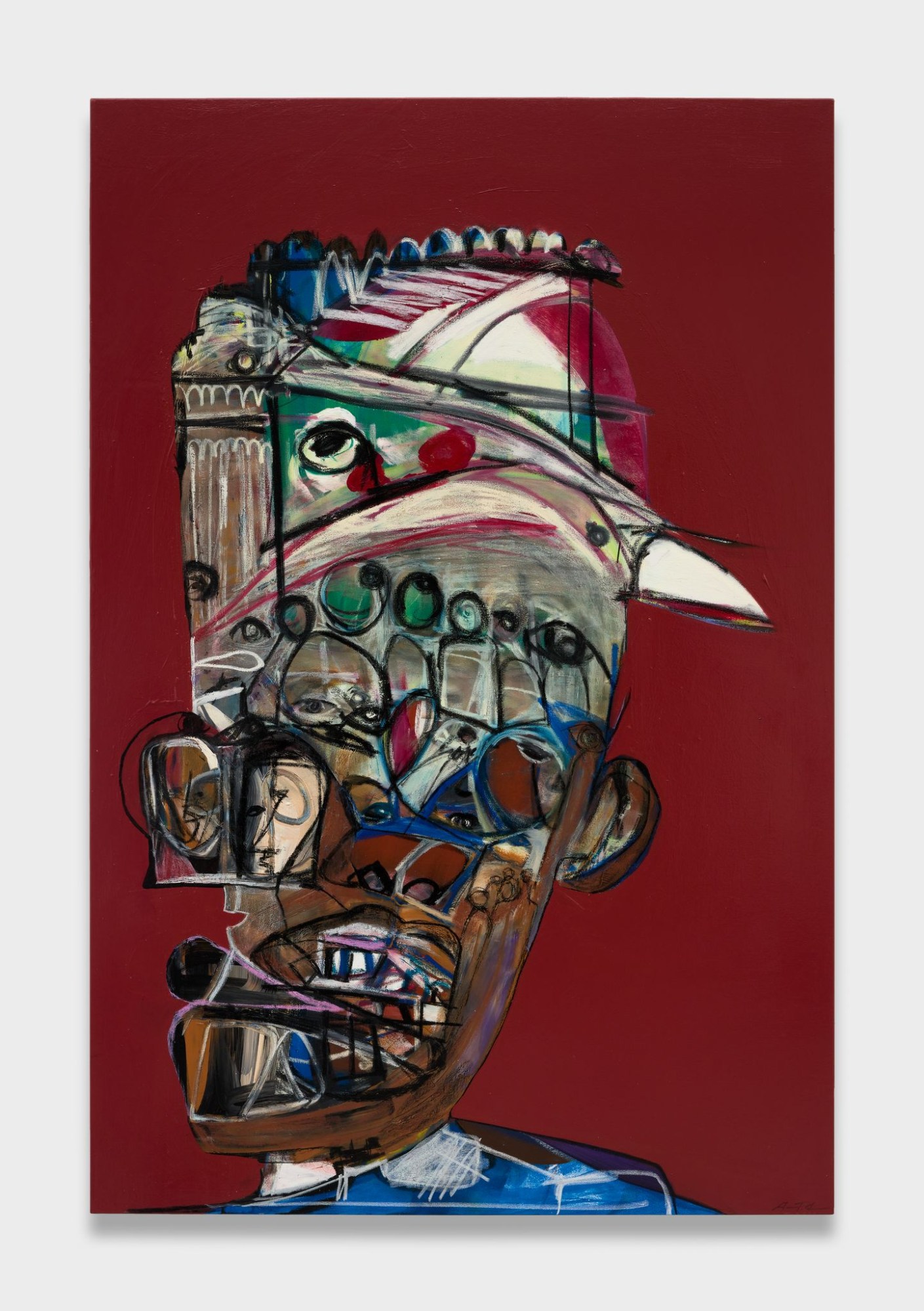

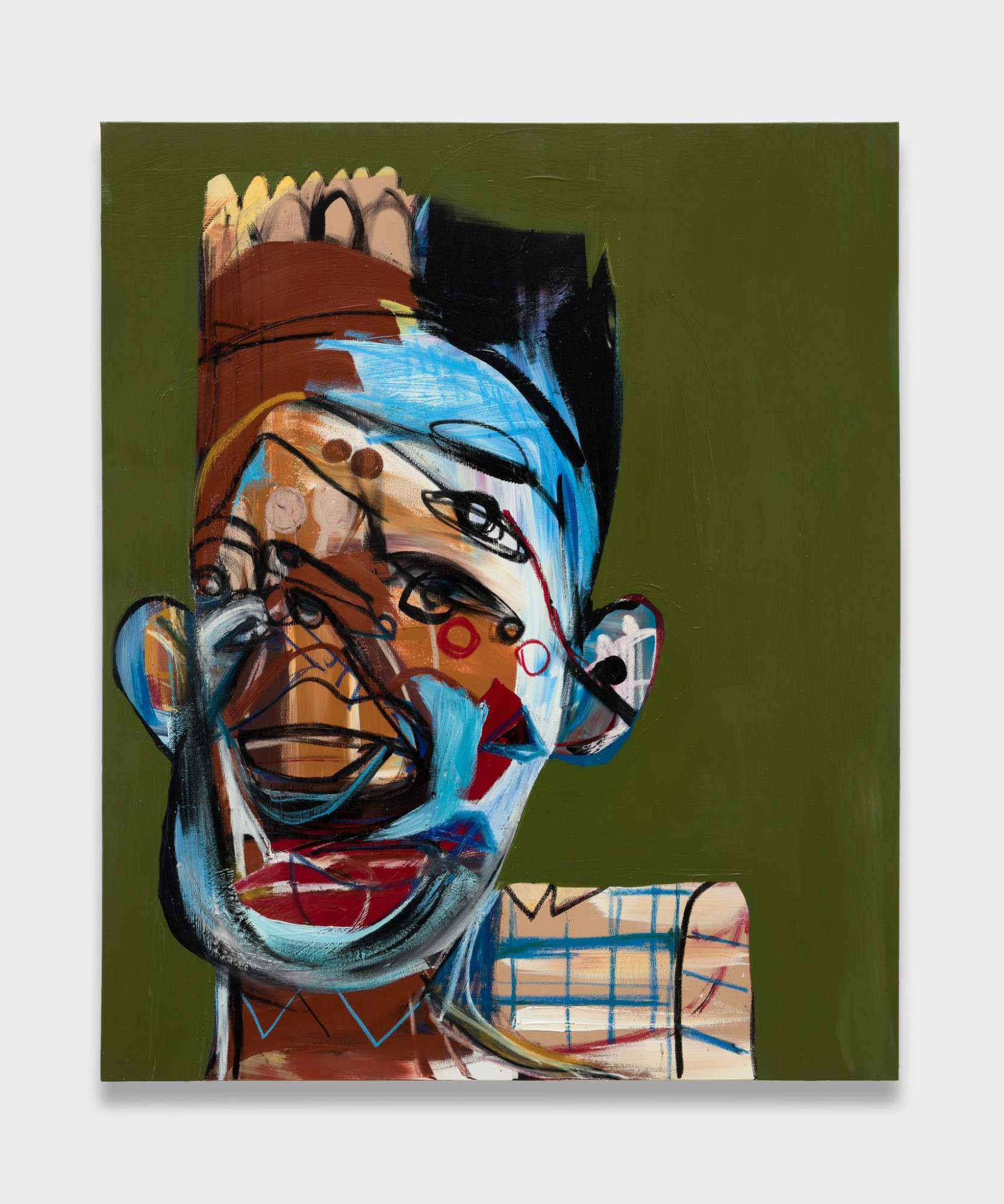

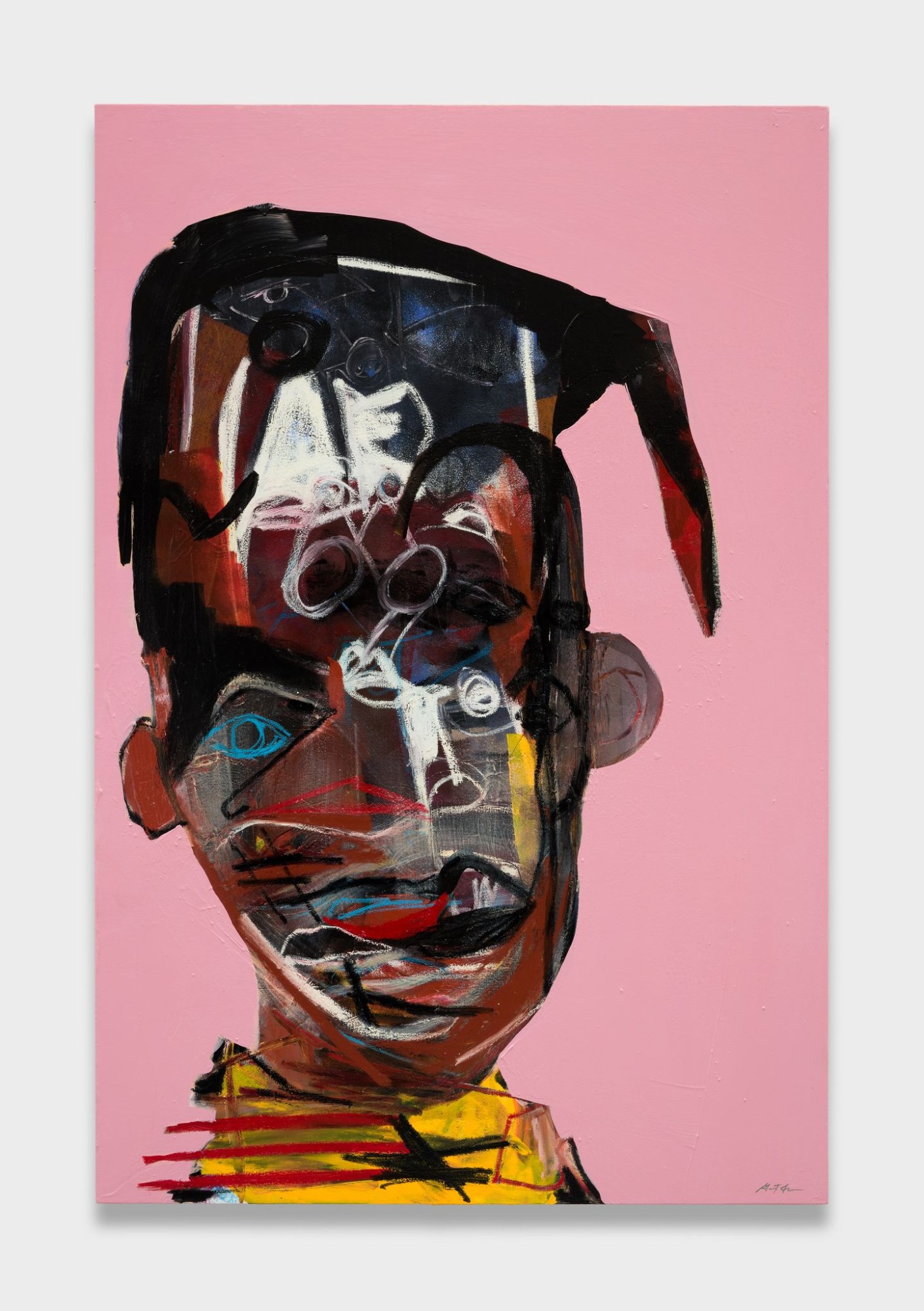

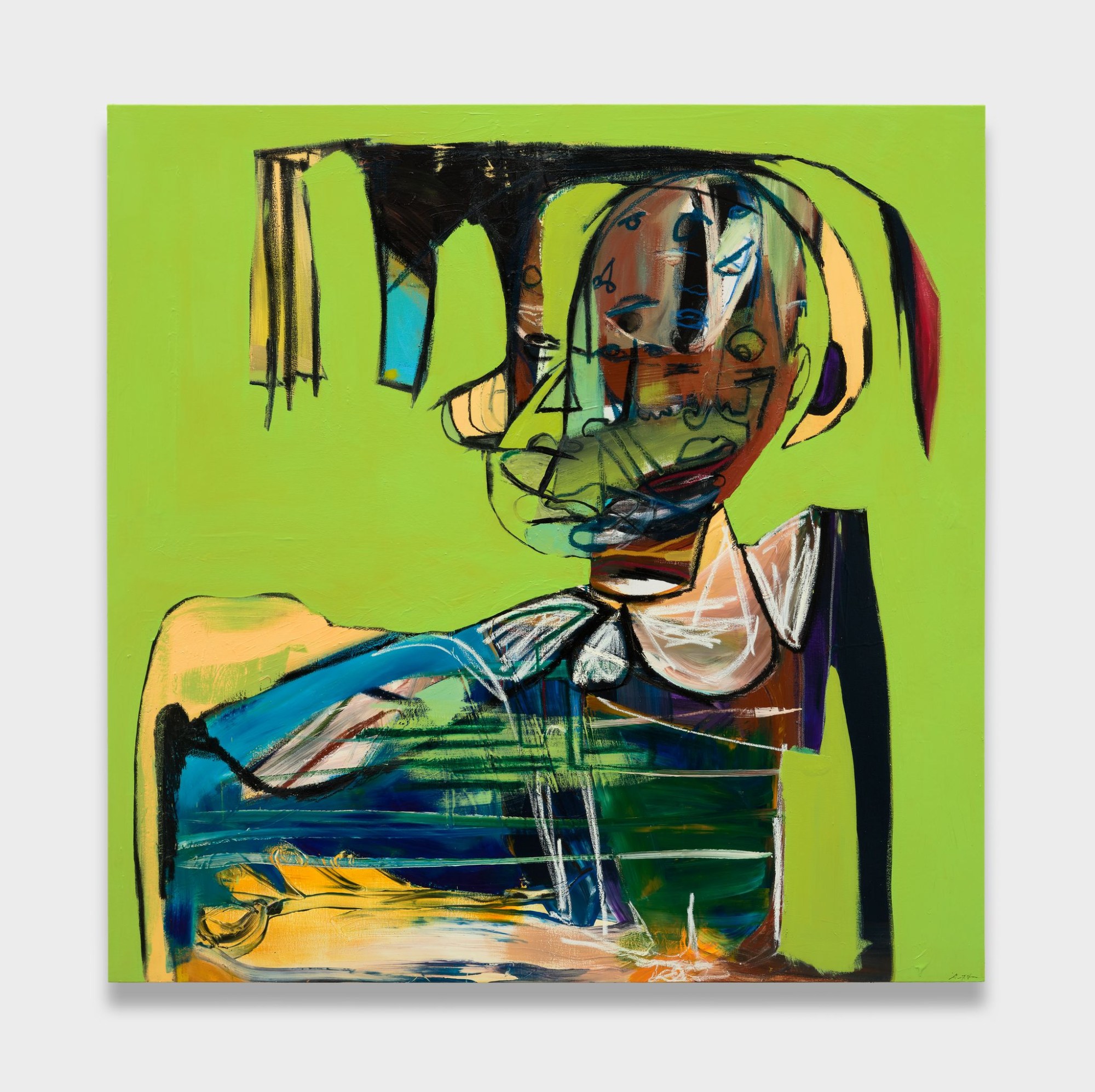

Following in that venerable tradition, albeit with a more contemporary bent, is Brooklyn-based painter Genesis Tramaine. In her first solo show, The Parables of Nana at Mayfair’s Almine Rech Gallery, she explores Biblical allegory through the prism of West African visual history and her own relationship with Christ, hybridising a Klimt-esque style of portraiture with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s flair for affective abstraction.

Brought into relief by their colour-blocked backgrounds — in hues from olive to ochre and sky blue — the figures in her portraits appear almost intimidatingly abstract. And yet, they still invite lengthy inspection, with wide ranges of emotion and experience readable in their frantic brushstrokes and ‘misplaced’ facial features. Few would say that Genesis’s paintings offer much in the way of comfort, but the intensity with which they communicate the artist’s vision is enthralling to say the least.

The sense of ‘distortion’ with which you’re confronted on first glance, however, is not born of a wilful attempt to shock. Instead, it comes from a desire to portray faces typically denied entry to spaces like churches and lofty art institutions in a light unconditioned by the roles they are often expected to play within them. A black queer woman raised in a Southern Baptist family, she hopes to make clear through her work that “we’re all invited into the church as queer saints,” she explains. “It’s very important to me that that is pushed into the narrative, make it uncomfortable,” for those that might otherwise protest.

We spoke to Genesis to learn more about how spirituality fuels her practice, her experience of visions, and her desire to shift narratives around blackness in contemporary art.

The Parables of Nana: it’s quite an evocative title — what’s behind it?

It’s actually a reference to my grandmother, my first teacher. When I was a child, I was given many tools. The first was my hands, and the first thing put in them was a book. My mother taught me to read, but my grandmother taught me to comprehend. She was a school teacher for thirty years, but when she came home from class, her tongue would change, it was one of the first things that I noticed. She would always say “Sit down at the table and let me learn you something,” never teach. It was clear that, in that context, my job was not to speak, but to take information in.

She was also the first to pass the parables of Christ on to me, but I want the references around my work to feel inviting, as there are some people in this world that are turned off on hearing Jesus’s name. It’s not a trick or anything like that, I just want people to feel invited into the room. And then you can decide for yourself if you’d like to keep going.

And what do you hope they find on entering?

I hope that they find a moment of simultaneous silence and sound, that my work helps them on their journey to becoming their highest selves. And I really hope that my work is able to stand as a beacon of light for people who have been denied entry to spaces like the church. I mean, I’ve been denounced in church, and my wife and I have suffered horrific experiences in church. But all of that nonsense has fuelled me and it continues to fuel me. If it’s something I’ve worked through, then I’m sure that it’s something that people have dealt with before, which takes me back to how Jesus must have dealt with it when he was called out in the temple. None of this is about me, at the end of the day. If it were, I would paint flowers. I love flowers!

How do you go about combining your own experiences with wider historical references?

It’s a question that I really struggle with answering. I really love to read, and my name is Genesis, though it’s the one book that I struggle with every time. When my Nanny taught me to pray, she taught me that there’s a really specific power that comes from integrating questions into prayer. So I draw upon the Bible a lot, as well as on my misunderstandings, disagreements and agreements with it. I think that everyone should read the Bible, and not necessarily religiously — it’s such a key cultural and historical reference point. And if you look at it from that perspective, it allows you to be present with it in a different way.

I also often have visions, daily, in fact. And I’ve been told that, during them, I often seem aloof, because I’m completely out of the realm of where we typically exist. And I have no problem, in the middle of a conversation, acknowledging that a saint is present.

What your work depicts certainly seems to lie beyond the parameters of everyday human experience.

The way I work is by fully surrendering myself. And I don’t always land at a painting. Sometimes it’s an exaltation of praise that just feels good. I grew up in a Southern Baptist Church, and when the organ began, an energy would course through the floor of the church. And then the ushers would start up, and Sister so-and-so would start playing her tambourine. Regardless of what was going on just a minute before, it was, and still is, so uplifting — it’s like I’m floating for a moment, and I see so much happiness and so much joy. It’s a moment of rapture, completely unconditioned by time. That moment of praise feeds me.

My work is a physical manifestation of that praise. And the tool I use to express it is whatever the good Lord gives me at that moment: paint, a brush, or a squeegee; my hand, my foot, or my knee. It’s very much like a dance of praise, or the enunciation of a gospel song.

You explore biblical themes through the prism of West African history. What’s your particular relationship to West Africa, and how does that specific niche of the continent’s history inform your work?

Reading the Bible, you have to remind yourself that what you’re reading is from a white male’s tongue and read between the lines. When you pull back all of the bullshit, you realise that they are reflections of us throughout. Also, I’m a black woman living in America, you know, so even though West Africa is not somewhere my physical body has touched, I’ve been there, I’ve lived there. It’s ingrained in me. There’s nothing new about my practice, all of it has been handed down to me, and the West African influences in my work are part of that. It’s a reflection of where I’m from, as well as of where I’m going.

Formally speaking, the faces of the figures you paint often appear distorted.

I don’t think they’re distorted at all, they’re there just as they come to me. Black people have often been looked past, but the reality is that the world can’t stop looking at black folks. There’s no distortion, that’s exactly the way we look: layered. ugly, beautiful, anxious, excited, lovely, bright, brown, light, white, blue… all at once. That ain’t no distortion, that’s just how black folk look to me. And that’s how I see humanity more generally. The human experience is full of colour, we’re the ones that interrupt reality with race and all this bullshit.

You certainly don’t portray black faces in any of the roles they’ve typically been consigned to throughout art history. Instead, they seem to depict human experience in its full complexity. And what you choose to see in that experience is pretty much up to you.

Exactly. Also, it’s important to remember that the black narrative, unfortunately, has often been given to the world through a lens that is not our own. So it makes sense that my work may seem to be out of context when comparing it with how we’ve traditionally been allowed to be seen or shown. I disagree with much of the imagery that’s been fed to me. I literally draw and paint over it. It’s wrong. So instead, I say ‘Use me, Lord, I’ll help them see the truth, because this is some bullshit.’

I know that what I choose to do, and the path that God has placed me on, seems very unorthodox — most of it does. I’m not a fool in that respect, and I exist in the world like everyone else. But I don’t really give a shit about whether or not it works within a sanctioned narrative of how things are or should be. I don’t need to create wiggle room around my spirituality for people to lean in and understand my work, because those that can understand, will. That might make some people uncomfortable, but that doesn’t mean they’re not interested — it often means the opposite. And I think the more structured and developed my relationship with Christ becomes, the more the work intensifies and the clearer its message becomes.

Credits

Photography Matthew Kroening