“I’m just a guy with a sewing machine,” writes designer Gérald Lajoie, in an email correspondence, describing his debut capsule collection. It’s a humble statement, but it’s one that embodies the young designer’s down to earth ethos. “Earth” being the key word here: literally, the soil and all the flowers, vegetables and curiosities that spring from it. The designer’s first collection is, by and large, inspired by nature.

As far back as he can remember, Lajoie has been interested in clothing: dressing up, styling himself. At age 17, he began teaching himself to sew, using his step-mother’s sewing machine, mainly so he could modify or mend the garments that he already owned. Lajoie became more serious about making clothing two years later, after meeting photographer and friend Fatine-Violette Sabiri. “We started talking about shooting an editorial, but we had no experience or contacts, no idea of how these things went down. We started emailing a bunch of local designers. Everyone refused to lend us clothes, so I just said, ‘Fuck it; I’ll make everything myself.’ I made six pieces for that shoot. That kick-started my obsession, if I can call it that.”

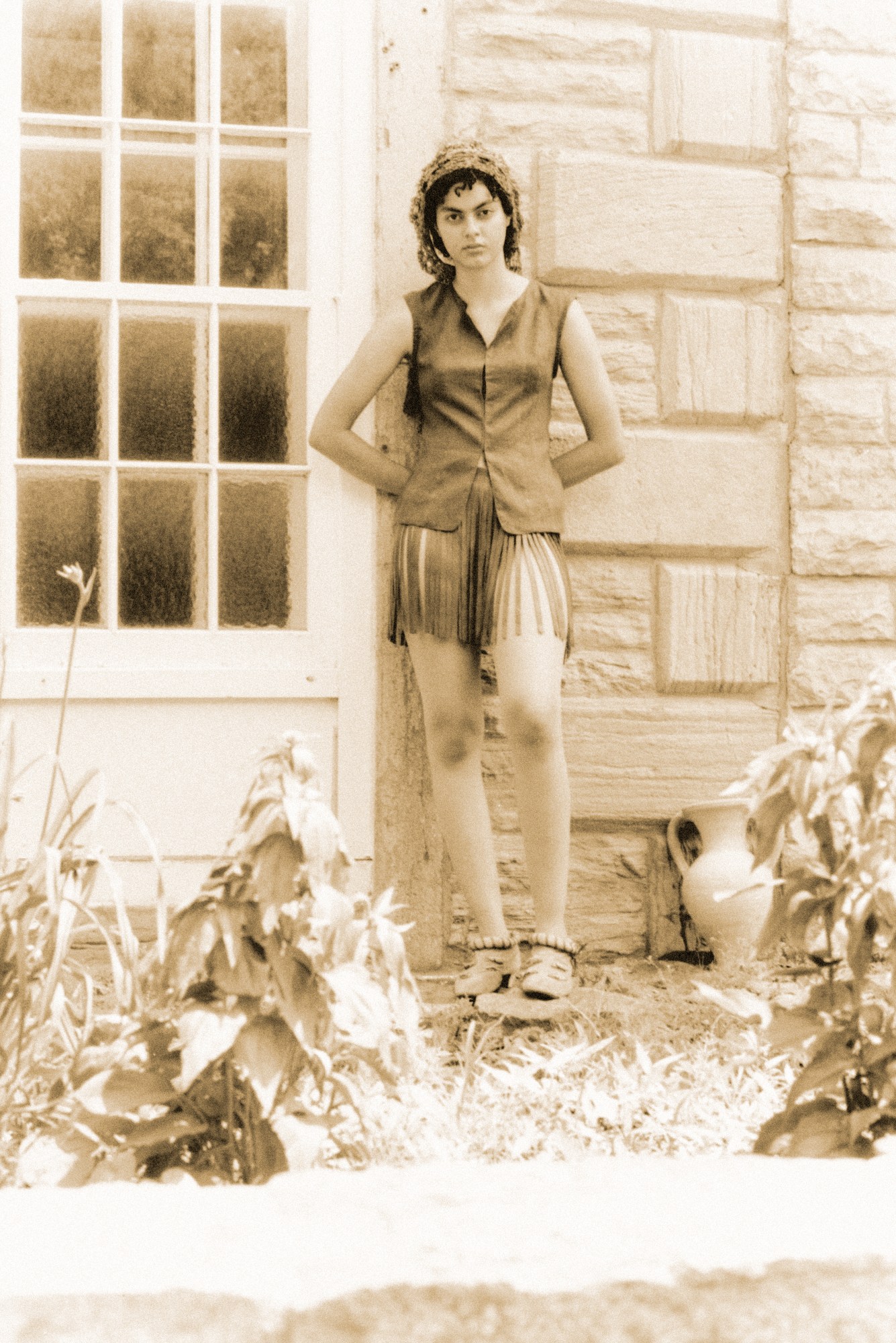

Five years on, Lajoie has launched his first fully-realized collection. “My lifestyle has inspired these designs,” Lajoie says. “I like wandering around the city and looking at things, smelling flowers on the sidewalk.” The collection’s designs speak to this urban pastoral. A blouse with sleeves that ruffle like the bushy petals of a peony. A triangle bra with tulip bulb cups. Crochet bonnets, created in collaboration with local knit label Çanta, that twist like ivy across the nape of the neck. A miniskirt with a low-cut waistband—“very sexy, but felt too modern”—is tempered with hand-stitched flowers, a crawling vine-cum-belt whose ends erupt into pillowy pistils. Set in the urban greenery, where Lajoie prefers to wander, the collection’s campaign was shot, naturally, by Sabiri, styled by François Gravel.

Nature serves not only as an aesthetic influence for Lajoie; it informs much of his design ethos. Creating clothes, to him, is like tending to his very own garden. “I try to treat fabric like flowers,” he explains. “I try to be caring when I work on a piece, respecting the fabric, listening to what it needs, what it wants. For me, sewing is very meditative.”

This mindfulness, taking time, is at the core of Lajoie’s creative process. He learned to sew by watching YouTube videos of fashion historians and bespoke tailors; their traditional, often meticulous and time-intensive, techniques are visible throughout his work. “I really created my own process,” he says. “It doesn’t at all reflect our modern standards or modern ways of working.” In Lajoie’s home studio, each garment is born from improvisation—no planning, no patterning—molded directly onto a mannequin and completely hand-stitched, from decoration to finishings. “Some pieces have as little as two machine stitches,” he notes, speaking specifically to one of the collection’s 3D-constructed garments. He points to the ruffles of a blue mini dress, “These are hand-stitched to allow them to breathe and live. If you machine stitch ruffles, they lay flat, they’re not as rich.” Two of the collection’s pieces—a dusty rose linen set—are hand-dyed from onion peels: “I came across this technique in an 18th century-living YouTube video. I’m kind of obsessed with these videos,” he laughs.

Naturally, Lajoie’s slow, thoughtful design process underlies the designer’s interest in sustainability, in both a small-scale and larger sense. “I put a lot of time and effort into every piece,” he says. “I like to think that there’s value in that, beyond trends and fashion.” It goes without saying that Lajoie isn’t keen on trends, or even on the modern definition of a fashion brand. “This isn’t a brand. It’s really just a project. I don’t really identify with the term ‘designer.’” he says.

As a result—and despite high demand for his garments—each Lajoie piece is a one-off, completely unique. Instead of producing his garments in numbers, Lajoie hopes to share his work in a different way, creating a community around the designs. “It’s weird right now because there’s a pandemic going on. I want to share my process and knowledge with my friends and followers. Making my patterns available for people to download, so they can make themselves a pair of shorts or a bag,” he says. “Or making videos to teach people specific types of stitching. I think it’s nice to motivate people to try to repair things themselves; I repair things for people all the time. I think it’s important to be respectful of your material possessions. I just want to share that mentality through my work.”

At the end of our conversation, he expands on his ethos, why he started this project, “It’s a mentality; it’s not just sewing. Our modern way of thinking about things is about growth and expansion. I’m trying to shift toward a more human way of doing things. Slowing down.”