Recently, it’s been increasingly difficult to come up with things that are especially great about Great Britain. One of the proudest hallmarks of this country, however, is, without doubt, the cultural mosaic that results in the creative vibrancy that our little cluster of islands is known for. But despite the disproportionate cultural wealth that the UK’s diasporic communities have offered this country, these communities have, historically, received little of the recognition and respect they deserve in return.

This stands particularly true for the country’s black communities, which, despite having been a guiding force across global creative culture, still fail to be recognised in the formal institutional contexts that white creativity inhabits as a given. In a reversal of this discriminatory trend, Get Up, Stand Up Now, a landmark exhibition surveying and celebrating the impact of black creativity in Britain and beyond its borders across 50 years has just opened at Somerset House. “There have been some exhibitions on black creativity before,” says Zak Ové, the exhibition’s curator. “Often they aren’t given such a big platform or even if they are, it’s cyclic, a programming trend that’s then forgotten again for another decade. It needs to be more consistent.”

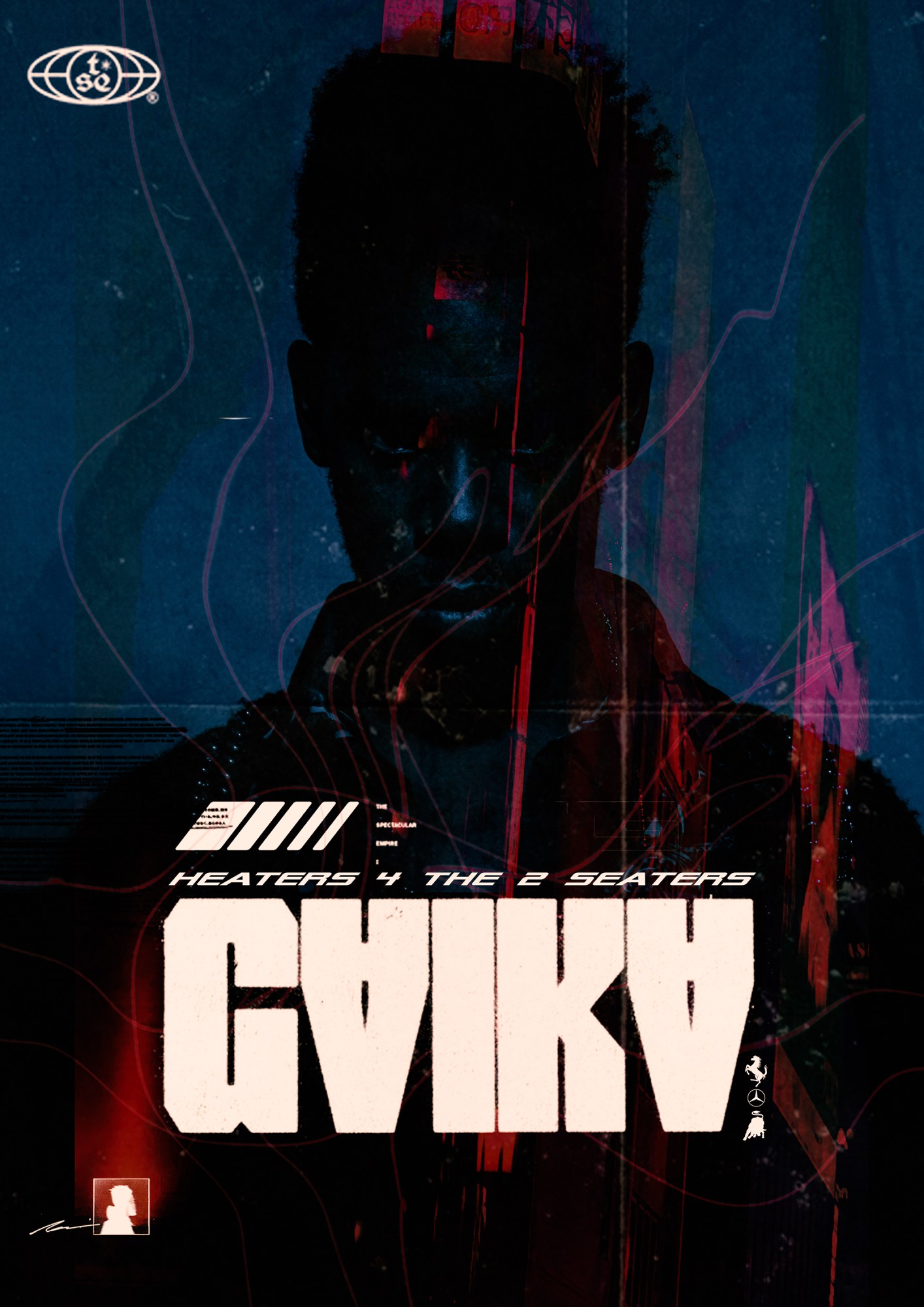

As you can probably imagine, taking stock of half a century’s worth of black contributions to culture at large is no small task — approximately 100 artists working across art, film photography, music, literature, design and fashion have contributed work. Chris Ofili, Ronan Mckenzie, Mowalola Ogunlesi and Gaika are just a small selection. Though the subject matter may be global, the seed from which the show grew was sown close to the curator’s home.

As the son of Horace Ové, the acclaimed creator of the first feature film by a black British director and member of what is now known as the Windrush generation, Zak chose the work of his father and his contemporaries as the exhibition’s starting point. “I was born into an artistic family and brought up in an extended artistic family,” he explains. “Many practitioners of the Windrush generation became parental to me. So, quite literally, I began with all of them.”

From here, he explores the lines of communication between their works and artists of the following generations that looked to them for inspiration, resulting in the exhibition’s broad, interdisciplinary scope. Yet, while the exhibition may trace the creative expression of the black experience across generations and mediums, it’s in the commonalities of that experience that Zak anchors the show. “Regardless of age and boundaries, I realised there was a shared experience throughout these different mediums and timelines, and throughout the diaspora. This is why the show is thematic, rather than chronological.”

Perhaps an even more powerful binding force, however, is the urgent, uncompromising nature of the works on show. Overcoming the restrictive tendency to pigeon-hole black creativity in a way that makes it understandable to a mass, predominantly white, audience, the works on show celebrate and grapple with the personal and political complexities of modern black identity on their own terms. “You’ll find that many of our Get Up, Stand Up Now contributors have never waited for a commission, because it probably would never have come to them,” Zak explains.

“These people have broken ground because they got on with creating something that so heartfeltly spoke about the issues they face,” he continues, “rather than hanging on for someone to recognise it along the way and ask them to produce it, and their work has truly connected. The importance of the exhibited works is this sense of pride, not worrying if it’s allowed or not. The artists are saying: ‘This is my soul, my beliefs and my ancestry, and I want to revere it.’ Get Up, Stand Up Now is the school of loud, proud and unbowed.”

And yet, as we look back on how the horizons of black creativity have broadened over the last 50 years, another question arises: how will those horizons continue to broaden over the 50 years to come?

Zak Ové “I’m witnessing a process of acceleration — we’ve come further in the past 10 years than in the previous 40 combined, so I think only more change can come in the next 50. Institutions that used to be completely closed to us have opened up their doors; I never thought I’d exhibit in the British Museum, for example. It’s great that they are looking at what our experience has become today, but what we really need are our own institutions, like the Studio Museum in Harlem, or more black directors and curators in existing ones. We need to decide what is important and we need the opportunity to become specialists not only in the making of it, but the promotion of it too.”

Gaika “I think our horizons have always been creatively broad. Black creativity was, is and will always be powerfully enigmatic. That said, I think in the next 50 years we will hopefully see a levelling of the playing field in terms of how our creations are valued and, hopefully, where they are held.”

Larry Achiampong “I see there being more complex and nuanced ideas being brought to the table. I hope to see contributions from women, LGBTQ communities and the working-class given more space. I’m also looking forward to stronger bonds and connections between the diaspora and those born within the African continent.”

Satch Hoyt “In comparison to black Music, we have witnessed extremely slow progress in regard to the acceptance and embrace of contemporary black visual arts. In my circle, we simply call it erasure. The visual art world has and continues to be controlled predominantly by white males, whose non-inclusive policy in regard to black artists has, in the last few years, somewhat changed. At the risk of sounding somewhat cynical: economics has played a substantial role in this new acceptance of black art into the art market — lord knows there was never a question about talent!

With the inclusion of black art historians, curators and directors in the institutions, and black scholars in our art schools, I believe we can look forward to an international art space that will contain an equal amount of black artists from the African diaspora and the African continent. In the future, we will witness a much more even representation of black British artists who will be included in diverse museum exhibitions that address all topics — not just the current trend of only being invited to participate in exhibitions that predominantly investigate identity politics. For many centuries, black culture has played a key role in the British narrative. The cultural diversity we witness on our high streets and in our daily lives must be exemplified in our museums and galleries.”

CCH Pounder “You never quite know how it’s going to go, and how future political situation will frame it. I know there’s a current feeling for afro-futurism, but I’m not sure exactly what it will turn into. More and more, however, we’re deciding what that will be and how it will look, rather than reacting to an outside force. That’s probably one of the most fascinating and wonderful things about the broadening of these horizons. We no longer have to go to museums and respond to the masters we see in them: we’re able to create on our own terms.”

Ronan Mckenzie “I think there will be more opportunity and space to create and share work that isn’t just about the black experience. I think it’s really important that shows like this exist, but going forward, it’s really important that shows can exist about so many different topics in different places, without being so rooted in identity politics. Not that it isn’t important! But there’s so much more to being a person than your race.”

Get Up, Stand Up Now, in association with Hennessy 12 June – 15 September, Somerset House, somersethouse.org.uk