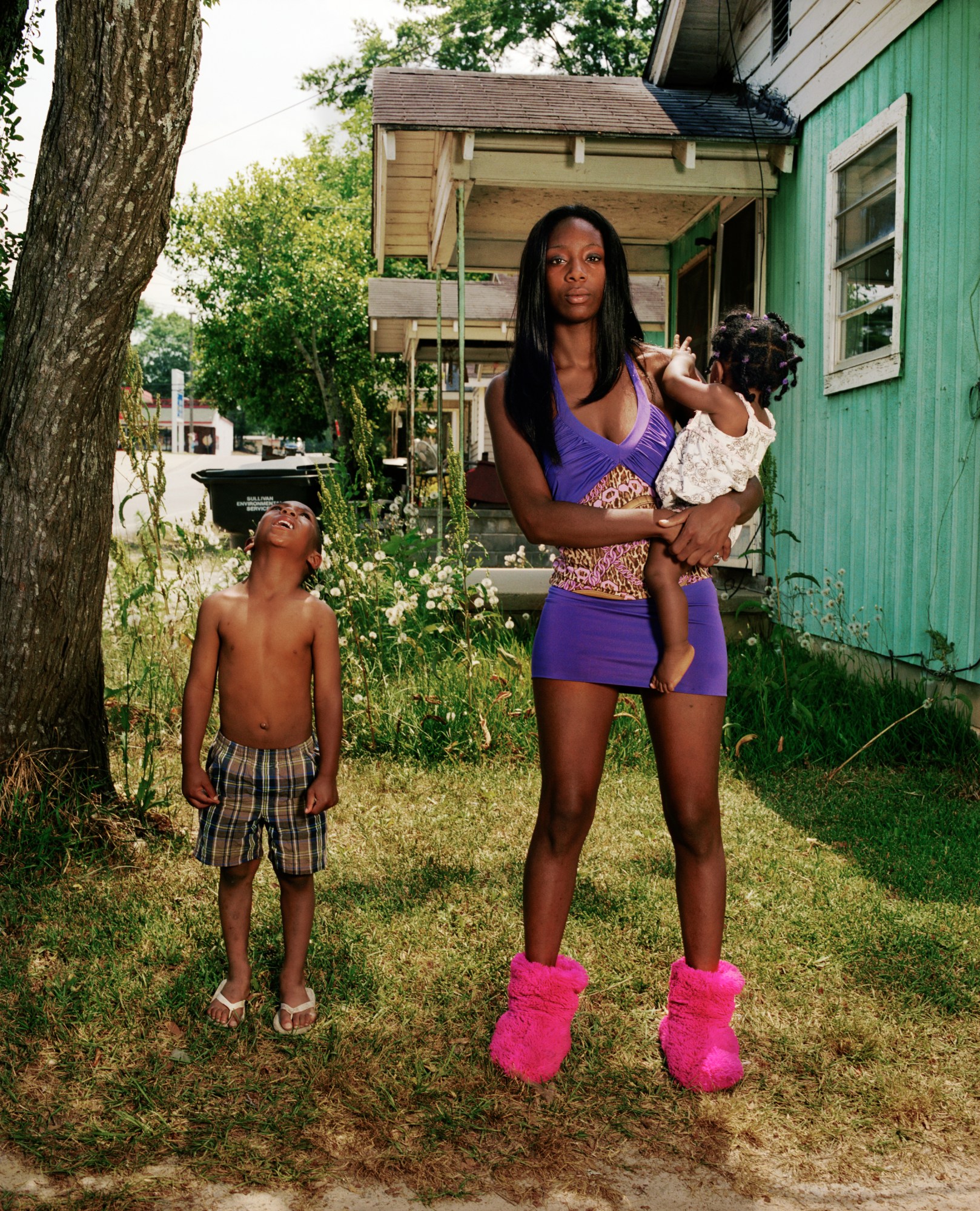

Photographer Gillian Laub has spent the past two decades investigating conflicts, tensions and relationships in America. Since her earliest assignments, her lens has been guided by the same motivation; to shed light on gender oppression and systemic racism, and examine the disastrous effects of America’s evolving political climate on its citizens. From pageantry to the military, Gillian has observed this from many different perspectives.

Southern Rites, her ongoing photography project, began with a magazine assignment in 2002 that distills many of the aforementioned themes, and later spawned an accompanying documentary released in 2015. Sent to Montgomery County, Georgia, a region in the state’s rural heartland surrounded by open fields and farmland, Gillian began documenting its racially segregated high school proms and the community that insulated this relic of a different era. In the years that have followed, she has returned repeatedly, observing a community at war with itself as the contentious issue of segregated proms began to unravel.

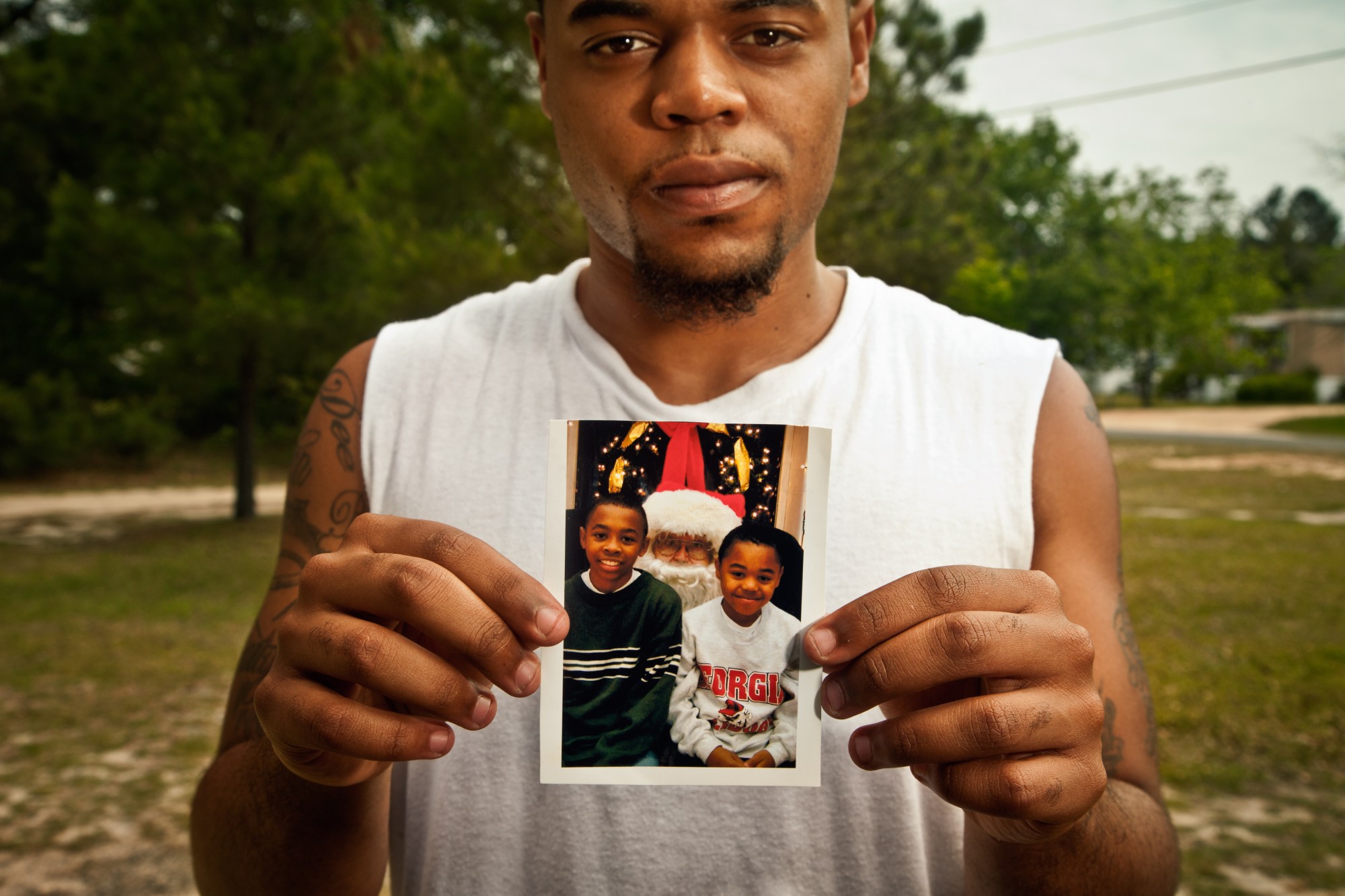

After her images were published in The New York Times in 2009, it wasn’t long before local teenagers were finally galvanised to break from their parents expectations and integrate their proms. But in the years since, the tragic shooting of a young Black man — Justin Patterson — at the hands of an older white man, plunged the city deeper into dissonance, polarising many and sowing the seeds for a presidency that (we now know) loomed in the not too distant future.

Like Dana Lixenberg’s Imperial Courts — a 20-year exploration of one of Los Angeles’ most deprived projects — Gillian has taken her time with this story, capturing the changes in its community slowly and cautiously, avoiding a myopic or imperious perspective. She continues to return to the region regularly and, following the release of her film and book in 2015, Gillian is now taking the exhibition of her images across America, to bring the story closer to those who might benefit from seeing it at such a pertinent moment.

“The bravery of the people who pose for me is what inspires my practice,” Gillian says. “My hope is that the stories I share help others feel less alone in the world and move the needle towards progress. Ultimately, I believe that is what art should do.”

To those who don’t know the story behind these pictures, what led you to Montgomery County, Georgia back in 2002?

I’ve spent over a decade working in Montgomery County, just about two hours southeast of Atlanta. My first trip there took place in November 2002, while on assignment for SPIN magazine. The magazine’s editors had received a letter from Anna Rich, a 19-year-old subscriber, who had written in the hope that someone would document an injustice that outraged her: the local high school’s racially segregated spring prom and autumn homecoming celebrations. Although the school was integrated in 1971, segregation of these events had continued. Throughout her time at Montgomery County High School, Anna had been forbidden to take her boyfriend, Lonnie, to her prom because he was Black. Despite her numerous, impassioned attempts to change things, including meetings with school administrators and students, her efforts were ignored or rejected.

By the time I visited Mount Vernon, Anna had graduated, so her younger sister, Julie — a freshman, also in a biracial relationship — acted as my chaperone. She introduced me to her friends, her boyfriend, and her parents. She took me to the best barbecue in town. She also showed me the ballot for homecoming queen that was handed out in every one of the school’s homerooms, a ballot that included nominees in two categories: “White Girl” and “Black Girl”. At the homecoming parade, two queens — one Black and one white — were perched on one of many homemade floats, both waving and smiling like political candidates. Later that evening, at the high school football stadium, kindergarteners from the local elementary school presented crowns to the queens: The young crown bearers were also segregated by race. I was haunted by this. And that is why I continued to go back over and over again.

Do you remember the very first pictures you took once you arrived?

I landed in the town on a Friday and went straight to the school’s homecoming parade. I remember the first images vividly — mostly because Montgomery County was not unlike the idyllic suburban town I grew up in. Homecoming parades happened with the same kind of jubilant celebratory passion of teenagers. Except one thing was different — this event was all divided by race. I will never get the image out of my head of the two young girls one Black, one white on the floats proudly smiling and waving. The seeming normalcy of it all was disturbing. I later found out that this ‘tradition’ was created when the school was integrated in 1971 (17 years after a Supreme Court ruling making segregation unconstitutional) as a way for there to always be a Black and white person voted in so they could be “separate but equal”.

How easy was it as an outsider with a camera in pursuit of a story, and did it become easier or harder as time went on?

When I first arrived in 2002, it was quite easy. People were very welcoming, warm, happy to talk to me and be photographed. I don’t think they realised the photographs had the power to expose something so nefarious that was happening in the community. When the work started to get published, my presence was no longer welcomed by the white community. I was threatened many times, chased out of town, and attacked by the county sheriff, even though I did nothing illegal.

The significance of this story right now barely needs stating. What happened at the election in 2016, and on streets across America in 2020, seem like almost an inevitability when observing the pictures in these series. How have you felt about the political and social landscape of the last four years, having spent so many years documenting the factions that contributed to it?

The past four years have been incredibly difficult. Although change happens slower than I would like, I did see some real progress throughout the time I spent in Georgia. Unfortunately, this administration has given permission for white supremacists to feel empowered and it’s truly scary. This upcoming election is so critical, it’s hard to sleep at night. I don’t know how we’ll be able to endure another four years of this. I am praying for a change.

It wasn’t until after your story was published in The New York Times that segregated proms ceased in the area when students decided to integrate. Was there ever a tangible shift in people’s attitudes and beliefs towards segregation, once outside opinions began to shape the community?

It was wonderful to see the students rejoice in the change that they were able to make by using their voices. Initially, many students were scared to share their stories for fear that they could suffer repercussions. I promised the story wouldn’t be printed until they graduated. Even if there were white families who were resistant to this change, they didn’t outwardly fight it. The first integrated prom felt triumphant and beautiful. These kids have known each other since kindergarten so it was the most natural transition for them.

Are you hopeful for the direction things are moving in?

I was very hopeful when I witnessed the energy of protesters this summer. It felt like there was an actual shift in the American consciousness. It’s sad that it took so long and for something so horrific to make this shift, but at least it was happening. I will be more hopeful when this administration changes hands. Until then, I am filled with a lot of anxiety, to be honest.

UMBC Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture presents ‘Southern Rites by Gillian Laub’ 15 October – 12 December. Admission to Southern Rites is free, with timed-entry tickets available here.

Credits

All images © Gillian Laub Courtesy of Benrubi Gallery