Torn from it or tied to it, the pandemic led many to grapple with the notion of home. Harry Styles – who releases his third album Harry’s House on 20 May – was no different. In a recent interview with Better Homes & Gardens, the 28-year-old musician said that, once he accepted Coronavirus was sticking around, he bubbled with some friends in Los Angeles. “I realised that that home feeling isn’t something you get from a house,” he said. “It’s more of an internal thing. You realise that when you stop for a minute.”

But as the endless flurry of post-pandemic music demonstrates, pop doesn’t wait around forever and Harry soon jumped back into popstar mode, writing and recording Harry’s House. Once you listen, you get a sense that that feeling – home being more than just bricks and mortar – is still pervasive.

Right now, career-wise, Harry finds himself scaling heights he’d previously only conquered during his tenure in One Direction. His second album, 2019’s Fine Line, was a huge critical and commercial success; in 2021 he scooped a Grammy for Best Pop Solo Performance with the song “Watermelon Sugar”. When he tours Harry’s House, he’ll do so in the most extreme manner possible, playing stadiums in Europe and 10 nights at Madison Square Garden in New York.

It’s no surprise then that the first single from Harry’s House, the brilliant, bouncing A-Ha-esque “As It Was”, has been number one for weeks. What was surprising, though, was the vulnerability that Harry, one of pop’s lasting enigmas, willingly offered up with the song. While there’s always been an emotional thread through his music, especially on the quieter moments of his self-titled debut like “From the Dining Table” or “Meet Me In The Hallway”, his lyrics have tended to shirk the exposing, narrative specificity that typifies modern pop. As he is in interviews, it always felt like Harry was keeping his distance, trickling out small tidbits about his life while guarding himself tightly.

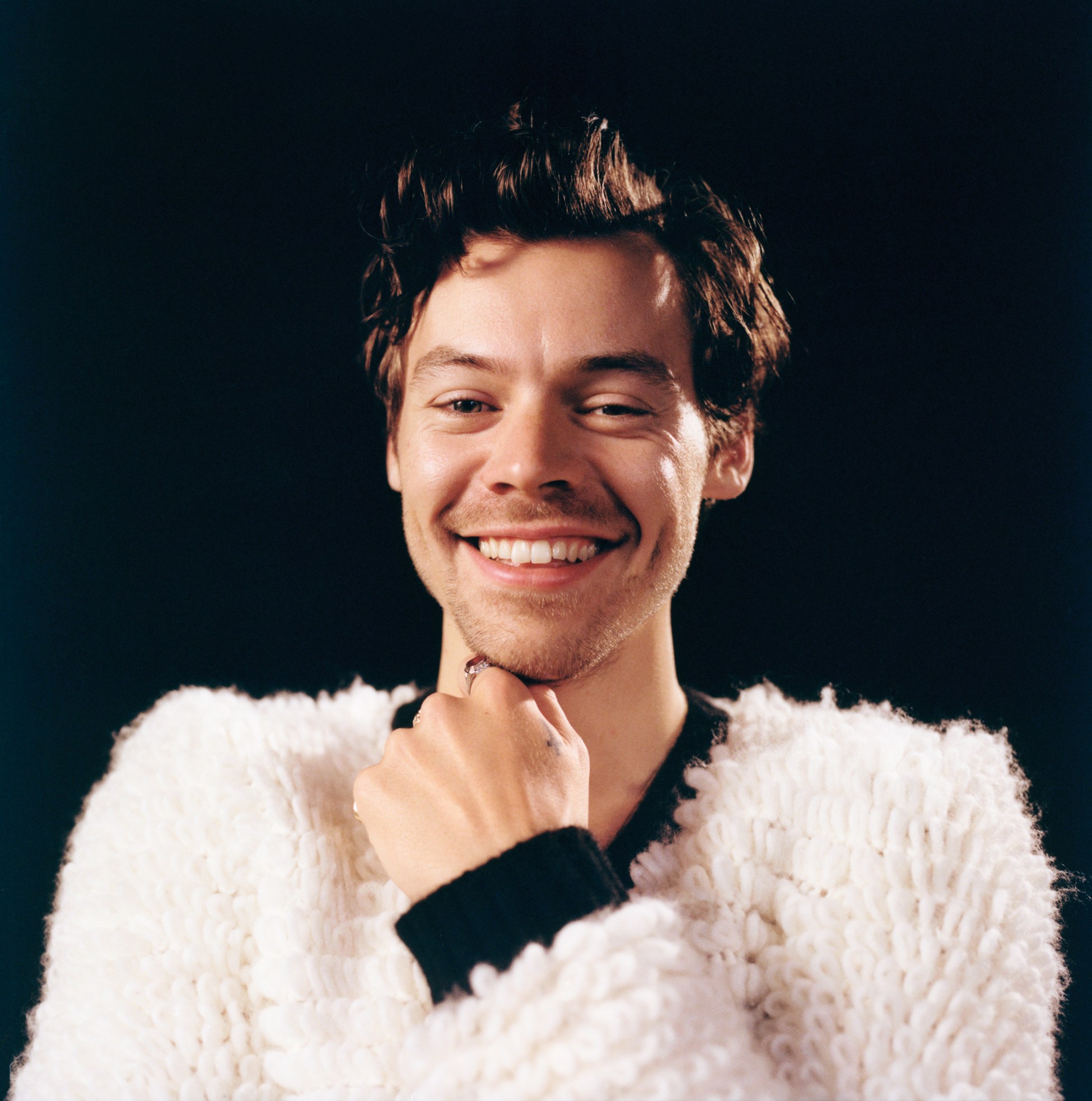

With “As It Was”, though, that armour slipped. With new softness, he unspools a little: “Answer the phone, ‘Harry, you’re no good alone/ Why are you sitting at home on the floor?/ What kind of pills are you on?’” he sings on the second verse, painting a rather different portrait of pop’s most genial star. Instead of the charming, toothy smile and twinkling eyes presented in magazine shoots and Gucci campaigns, Harry seemed self-isolating and avoidant.

He seemed to confirm this in his interview with Better Homes & Garden: “Whether it was with friends or people I was dating,” he said, “I was always gone before it got to the point of having to have any difficult conversations.” The stillness of the pandemic, he said, made him confront this, while five years of therapy led him to acknowledge that he had a tendency to “emotionally coast” through life. Harry’s House feels like the result of these realisations, an exercise in embracing joy, pain, loss and love in all their complexity.

Still, an almost perennial sense of optimism and euphoric romanticism are the most dominant moods. “Late Night Talking”, which he debuted at Coachella, feels lifted from a movie musical, swoon-y melodies and gleeful synths, reminiscent of Hall & Oates at their most ebullient, lifting Harry’s vocals into the clouds as he confesses, “Now you’re in my life/ I can’t get you off my mind.” The rather tongue-in-cheek “Grapejuice”, in which he sings about sharing an expensive bottle of red wine with a lover, is so jolly it feels like it should soundtrack summer days spent skipping down streets. And the groovy R&B of “Cinema” injects a little sexiness into proceedings, although it’s slightly tarnished by how on the nose it is. (He sings “You got the cinema/ I bring the pop to the cinema” — just to make sure listeners know that he’s a popstar and his girlfriend makes movies.)

But when the moony-eyed love-struck sweetness is tempered a little, the album comes alive. “Daylight” is filled with boyish enthusiasm, though the honeymoon period is disrupted by an undercurrent of longing and obsessiveness. Distorted guitars turn the repetitive refrain of the chorus (“You got me cursing the daylight…you’ve got me calling at all times”) from cute to concerning, as if Harry’s affections are so overpowering that they become uncontrollable. “Satellite” similarly finds tension between the singer’s romantic fervour and its recipient: “Spinning out, waiting for you to pull me in,” Harry sings over whirring guitars, sun-dappled synths and the crash of cymbals. “I can see you’re lonely down there/ Don’t you know that I am right here?”

Harry is self-aware, though. “I disrespected you / Jumped in feet first and I landed too hard,” he sings on “Little Freak”, a song that feels like an ode to a paramour but, when peeled back, seems to acknowledge his obliviousness to another person’s desires. The folksy trill of “Boyfriends” belies its dark subject matter: “Boyfriends/ They think you’re so easy/ They take you for granted/ They don’t know they’re just misunderstanding you,” he sings on the first verses, seemingly admitting to his own past discrepancies and toxic behaviour. And on “Love Of My Life”, over the buzzing synth bass and muted plucks of an electric guitar, he mourns for a relationship forced apart by distance, admitting: “I don’t know you half as well as all my friends/I won’t pretend that I’ve been doing everything I can/ To get to know your creases and your ends.”

There seems to be a sense of, if not equilibrium, then acceptance on “Just Keep Driving”. During the verses, Harry reels off various objects and experiences like polaroid pictures, creating a collage of a relationship that’s both dreamy and romantic but also unsteady; at times unhealthy. “Cocaine, side boob, choke her with a sea view/ Toothache, bad move, just act normal,” he sings on the final verse, his voice soft against the growing aggression of a guitar, although everything ultimately cools, life carrying on: “Moka pot Monday/ It’s all good, hey you/ Should we just keep driving?”

The picture of domesticity painted by “Just Keep Driving”, one that concedes that life and love can often be fraught, feels like an encapsulation of the thematic journey of Harry’s House. “I think that accepting living, being happy, hurting in the extremes, that is the most alive you can be,” he told Better Homes & Garden. The record’s overarching exuberance certainly supports this outlook, although it can feel like Harry didn’t quite plump his darker crevices. While certainly honest and discerning when admitting to his own shortcomings, Harry’s House is still a little bit reluctant to lay its author bare for all to see.

But this is Harry’s house and he makes the rules. In the home he’s constructed for himself, one made up of memories, vulnerabilities, admissions and happiness, he seems to be at peace. What’s more, he’s cracked the front door open, and for the first time seems to be inviting us to look around and explore it ourselves. For now, Harry Styles is content in showing us what he feels comfortable sharing. There might still be bodies buried in the basement — perhaps, on album four, we’ll learn more.

Harry’s House is released on 20 May. Pre-save or pre-order it here. Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on Harry and music.