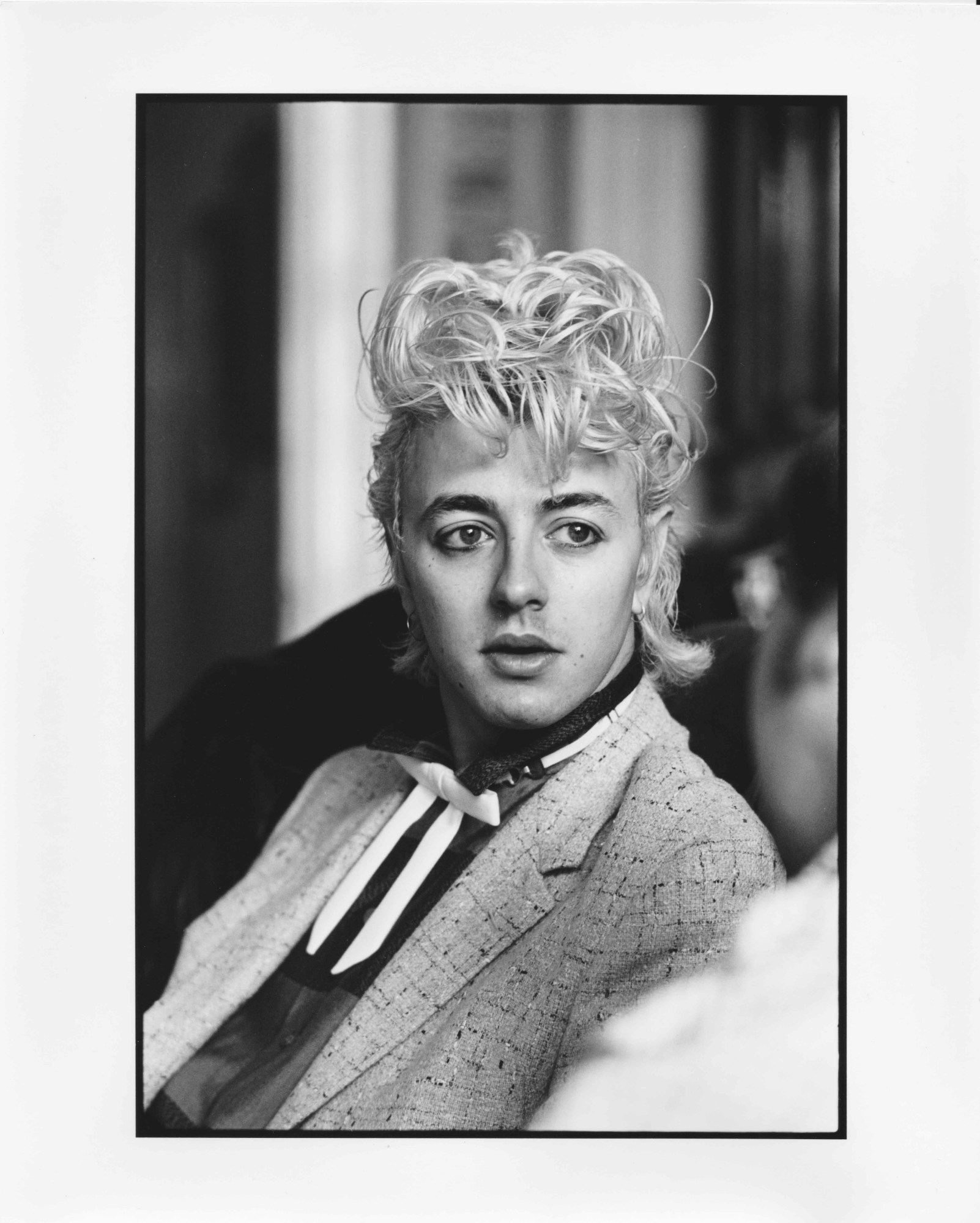

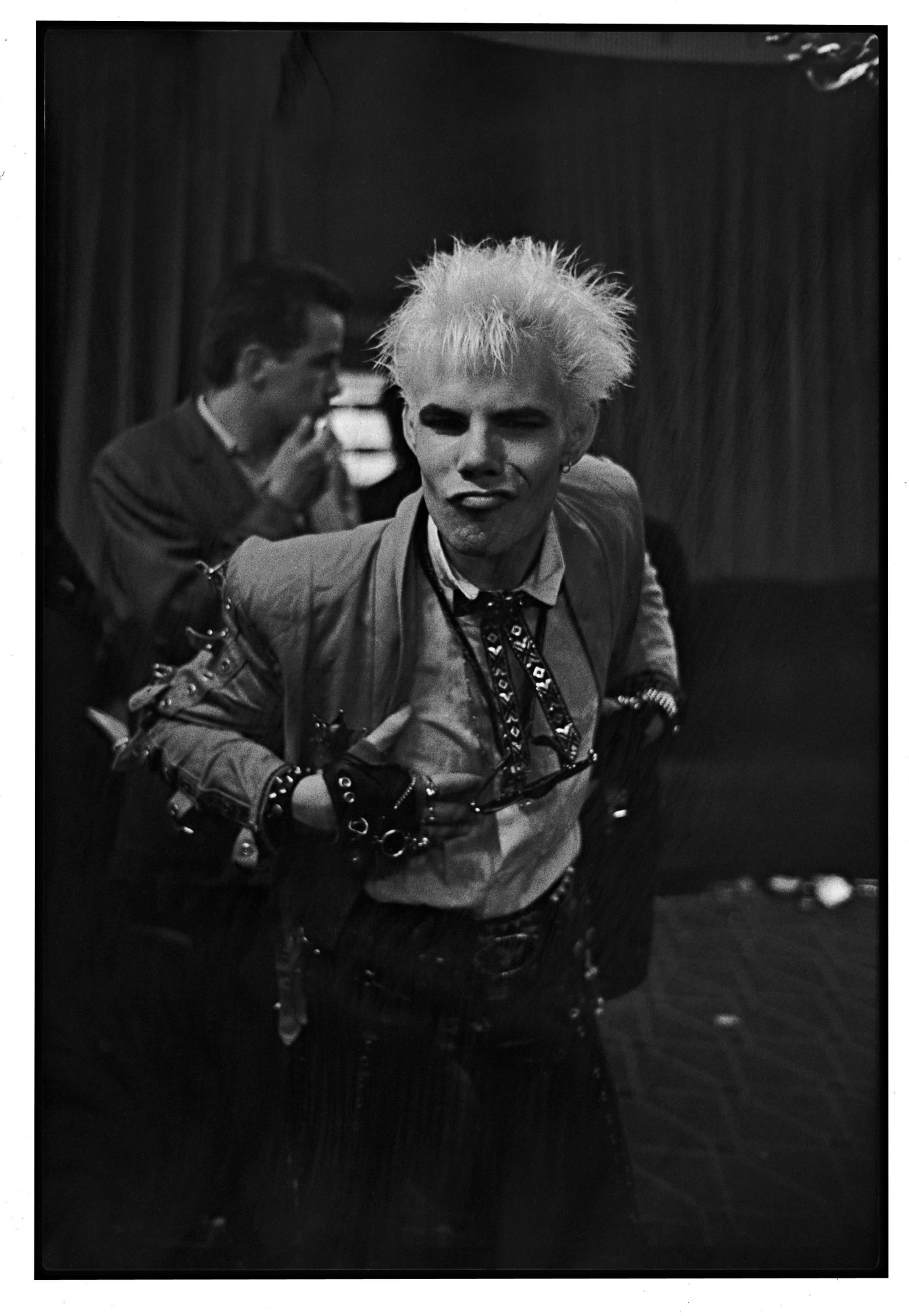

Herbie Yamaguchi was living in London when the punk movement burgeoned four decades ago, and specialized in portraits of British musicians from about 1975-1985. The Japanese-born photographer was a small-time actor (part of the musical company “Red Buddha” led by Tsutomu Yamashita) and a freelance photographer for a Japanese music publication. He spent his time living on other people’s floors, and at one point was the flatmate of Boy George (whom he photographed washing his laundry and lollygagging in bed). Yamaguchi met Michael Shrieve, a drummer for Santana and the first musician acquaintance of his photo career, as well as Steve Winwood from Traffic and Mitch Mitchell from the Jimi Hendrix Experience. These contacts opened him up to the music scene, compounded by assignments. He captured everyone from Bananarama to Psychic TV to Alan Wilder of Depeche Mode. Chronicling the development of this London subculture, he was able to access the offhand intimacy and unvarnished earnestness of young musicians trying to situate themselves—a much more compelling, lasting, meaningful look into an amazing era in retrospect than the polished productions of albums covers and posters.

Yamaguchi sat down in Paris to discuss how cameras brought him out of his shell, his friendship with Boy George, and how Joe Strummer of The Clash uttered words that would be decisive to his career: “You can click away of whatever you want. That’s punk!”

How did you enter into the music photography niche when you lived in London?

The first thing I did was participate in a Japanese theater company as an actor. I had no lines to speak—musicians were behind the stage, playing while we were acting. I liked music when I was in Japan, but when I met musicians in London, I started taking pictures. The portraits are very frank, friendly shots, instead of posing in a studio. My job was to photograph for a page of a Japanese music paper. The assignments were not as important as those for a record cover or a big poster, so the musicians didn’t care about my position. They never changed their outfits or put on makeup; they showed me their authentic daily lives. I knew some more famous photographers in London always taking those other kinds of pictures and I thought their jobs were better. I envied the famous photographers who could organize special shoots in their own studios. But the musicians wouldn’t have shown themselves to me in the way that they did, if I’d had all those things. I photographed as I could then. People say they have no time, no money, no confidence. But few people have those things. So go forward. Where you are standing now is already a good position.

What was your photographic practice before London?

I started when I was 14, in junior high school. Before that I played flute in a marching band. I was not good enough, so I “retired.” [laughs] I joined photo club in the school activities; I thought it was more suitable to me. But the theme for my photography was already there. I had TB as a baby, and my bones were decayed; I had to wear a corset for ten years. I couldn’t exercise at school. I wasn’t strong, I didn’t have friends. Girls in the classroom were not smiling at me; they picked on me. But when I started taking photographs, and pointed the camera at them, they smiled at me—at the camera. Photography helped me.

The musicians you photographed were often on the brink of success. Could you feel that in some way?

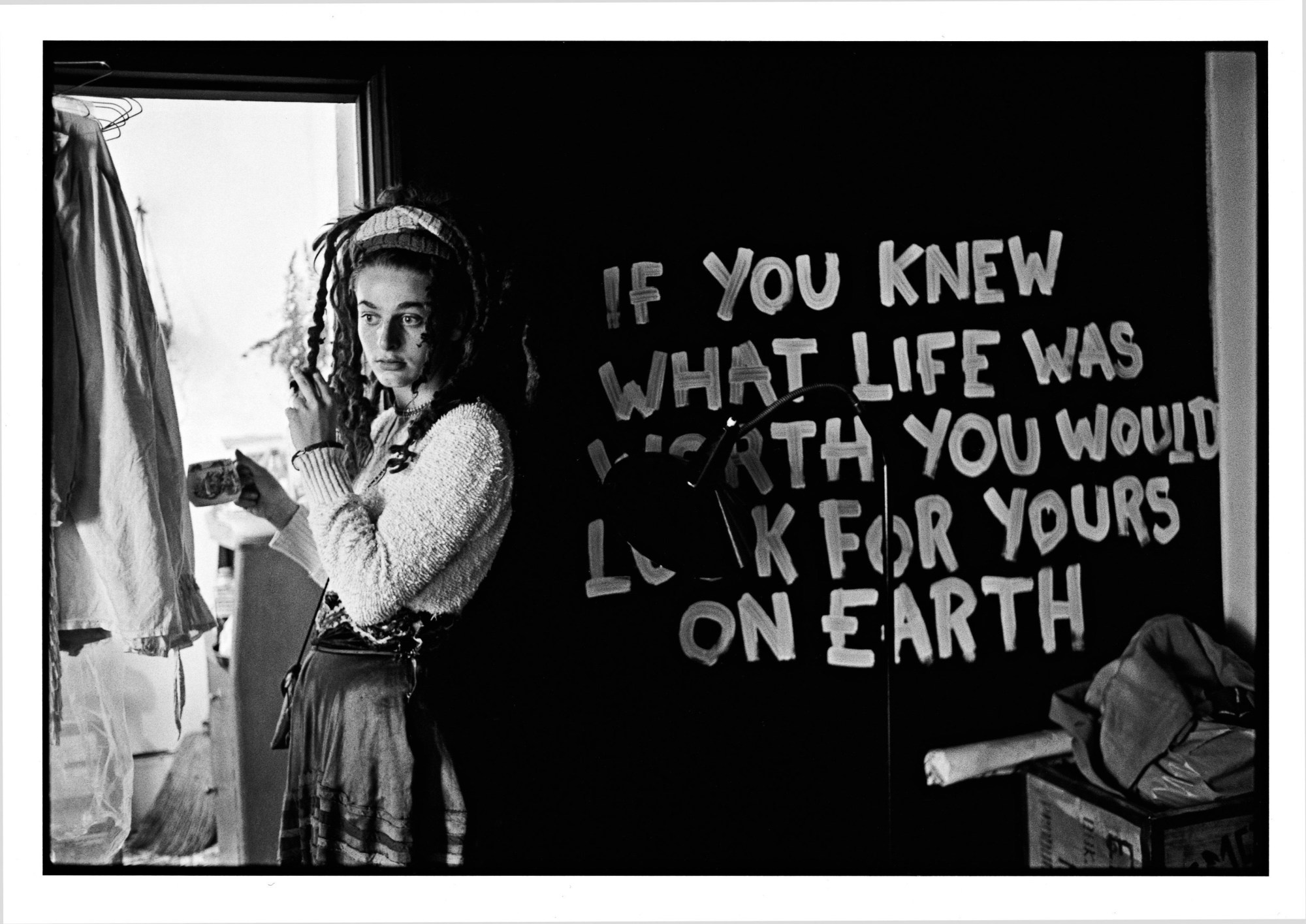

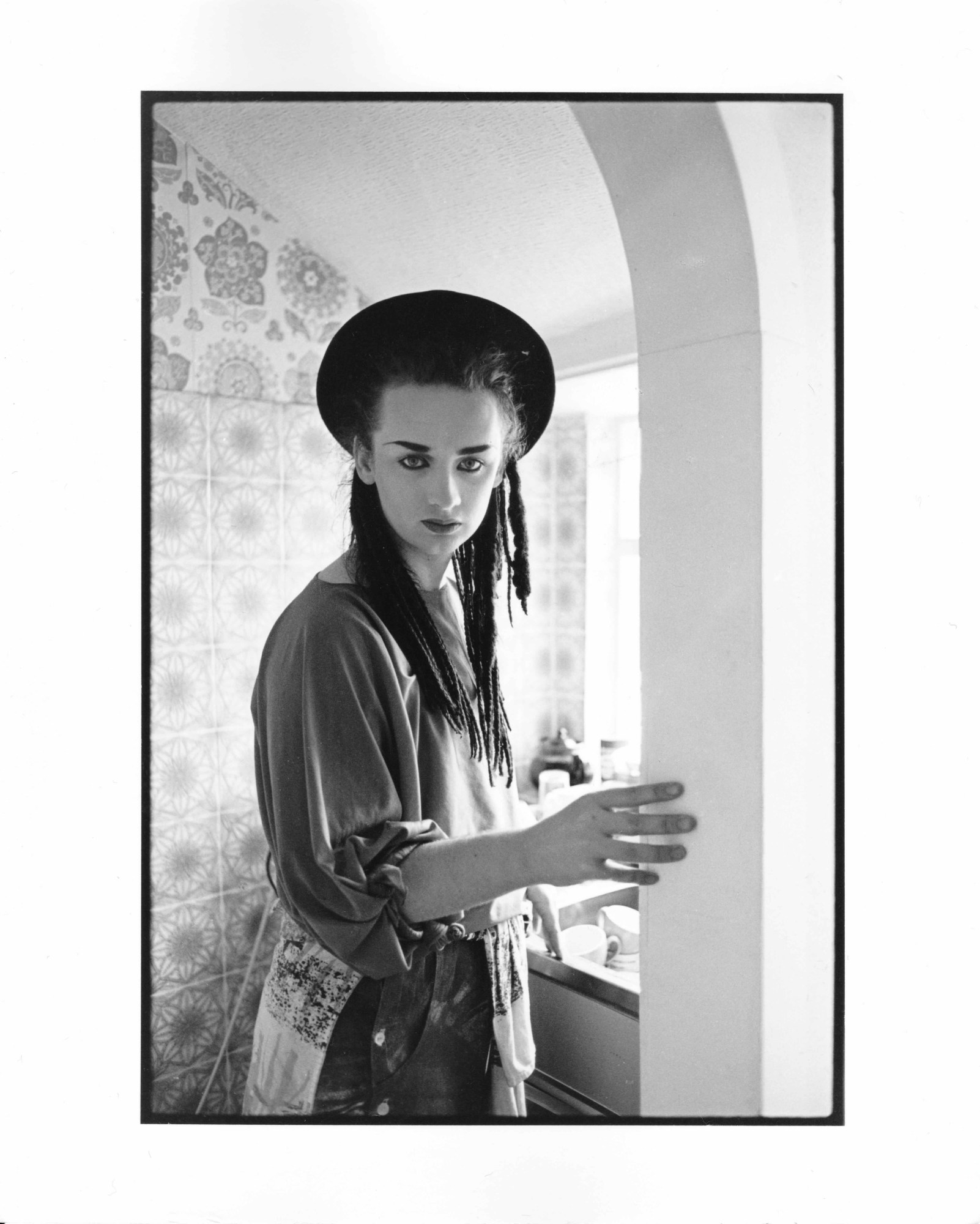

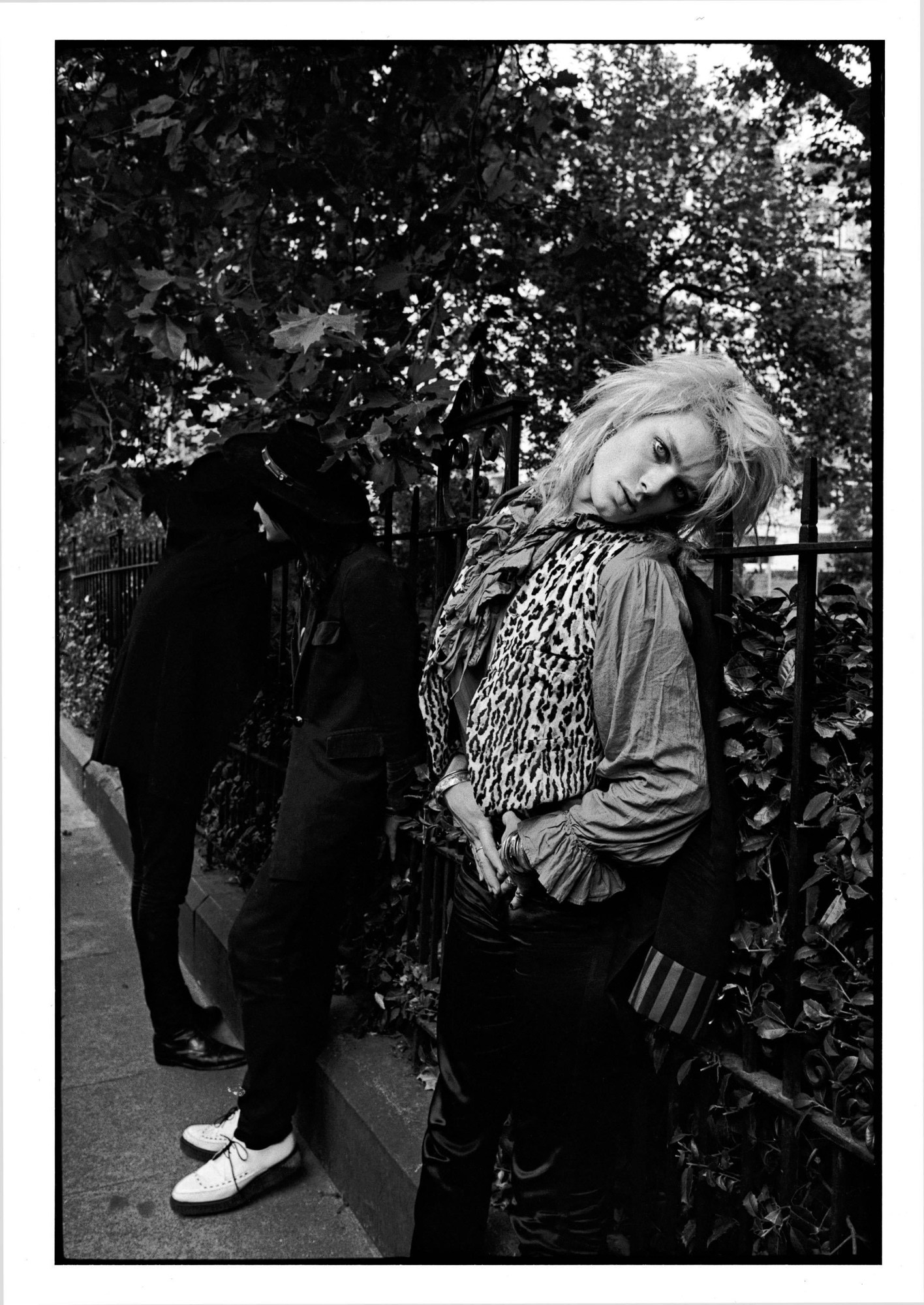

Certainly I felt some power in them. I met Boy George before he became famous; we just happened to meet. I was very poor and couldn’t afford to pay rent so I was staying on the floor of a friend’s flat on the same floor as he was—he was just called George then—and he became my friend. The photo of Susanne Freytag was taken at my house; she was part of a German band called Propaganda. I saw her onstage in Tokyo, but I happened to recognize her in Soho in London. Others were commissions, on assignment. Frankie Goes to Hollywood I photographed on their Japanese tour, as their official photographer. The filmmaker Derek Jarman happened to live almost next to me, in 1975. I used to live in a warehouse; the area was kind of abandoned, and artists moved in, paying little rent. Brian Eno was making music for his films. Spandau Ballet and Duran Duran I photographed regularly before they became huge; I was around during their beginnings. It gave us a much tighter relation. When Siouxie Sioux came to Japan, I was trying to get to the dressing room and they tried to stop me because it was private, but she saw my face, and she said “He’s good! Let him in!”

When I saw Boy George, he was already wearing women’s costumes. I saw his struggle: he’d been spit on and when he came back to the squat he looked lost. But he was quite determined. After overcoming that kind of hard time—he never compromised his attitude. I’d have stopped wearing those things, but he didn’t change his fashion, because his fashion conveys how he is, how he lives his life.

What was the tone of the shoots you did: friendly? Professional?

It depends on the music! I was photographing guitarist Gary Moore, and I asked him to pose: he refused. He’s a hard rocker. He said: we wouldn’t do this in normal life. So it depends on the type. Apart from regular assignments, I met Joe Strummer by chance. I’d previously photographed him on the stage, and once for a portrait. He didn’t recognize me, but I saw him on the underground platform; I was on my own. I was like Wow—but I didn’t have an assignment. So I went up to him and said, “Are you Joe?” And he said “Yes, I am.” I asked if I could take a picture even without an assignment. We got on the same train in the same direction. I took photos. At one point the train stopped when he was getting off, and light came in. He turned around and said that I should photograph whatever I want: that’s punk. That’s the title of the book. When I was in London, I wasn’t quite sure I could be a photographer, but what he said pushed me. I shouldn’t compromise. I have a radio show in Japan now and I’ve told my audience what Strummer said to me. It’s inspired other people to not compromise. A fifty-year-old truck driver emailed after the Joe Strummer story because, thirty years ago, he tried to be a photographer but had a family instead. When he listened, he cried, and he asked if it was too late to try again. I answered: “Not too late.” He should keep a camera on the seat of his truck.

Do you feel nostalgia when you see the photographs?

I captured all these people when they were at their most attractive. They’re like 50-60 now. Some of them lost some beauty! I photographed them when they’re shining. Sometimes I check their homepage and they look really different. I heard a rumor Boy George got fat but I was happy when I saw him in Japan, he was in good shape. We reconnected on Twitter. He asked me “Are you happy in Japan?” Asking if you’re happy is more than “How are you?”—it was quite warm. When he came to Japan on tour a few years ago, we had a big cuddle.

You Can Click Away of Whatever You Want: That’s Punk! is on view through July 8 at Galerie &co119, 119 rue Vieille du Temple 75003, in Paris.

Spandau Ballet, Covent Garden, London, 1981

Boy George on bullet train, Japan, 1983

Credits

Text Sarah Moroz

Photography ©Herbie Yamaguchi, courtesy galerie &co119