Heterosexuality is officially in its flop era. Last month, in another death knell for straight people, a viral article from Psychology Today revealed that “dating opportunities for heterosexual men are diminishing as relationship standards rise” amongst women. The author warns men that they need to start “seeing intimacy, romance, and emotional connection as worthy of your time and effort”, something that for many would seem blindingly obvious in the pursuit of a romantic relationship.

Straight women’s exasperation with men is fairly palpable these days. TikTok is awash with horror dating stories characterised by ghosting, rudeness, objectification, emotional immaturity, and a general lack of care. So many reality TV dating shows confirm straight men’s seemingly endless capacity to make women suffer, so often prioritising their own needs over those of their partner. The rise of the “podcast bro”, selling good old-fashioned patriarchal values, has shown that a significant and easily commodifiable response to women’s desires for higher standards from men is to double down on misogyny and tap into men’s entitlement to the bodies and free labour of women, rather than cultivate genuine feelings of mutual desire and love.

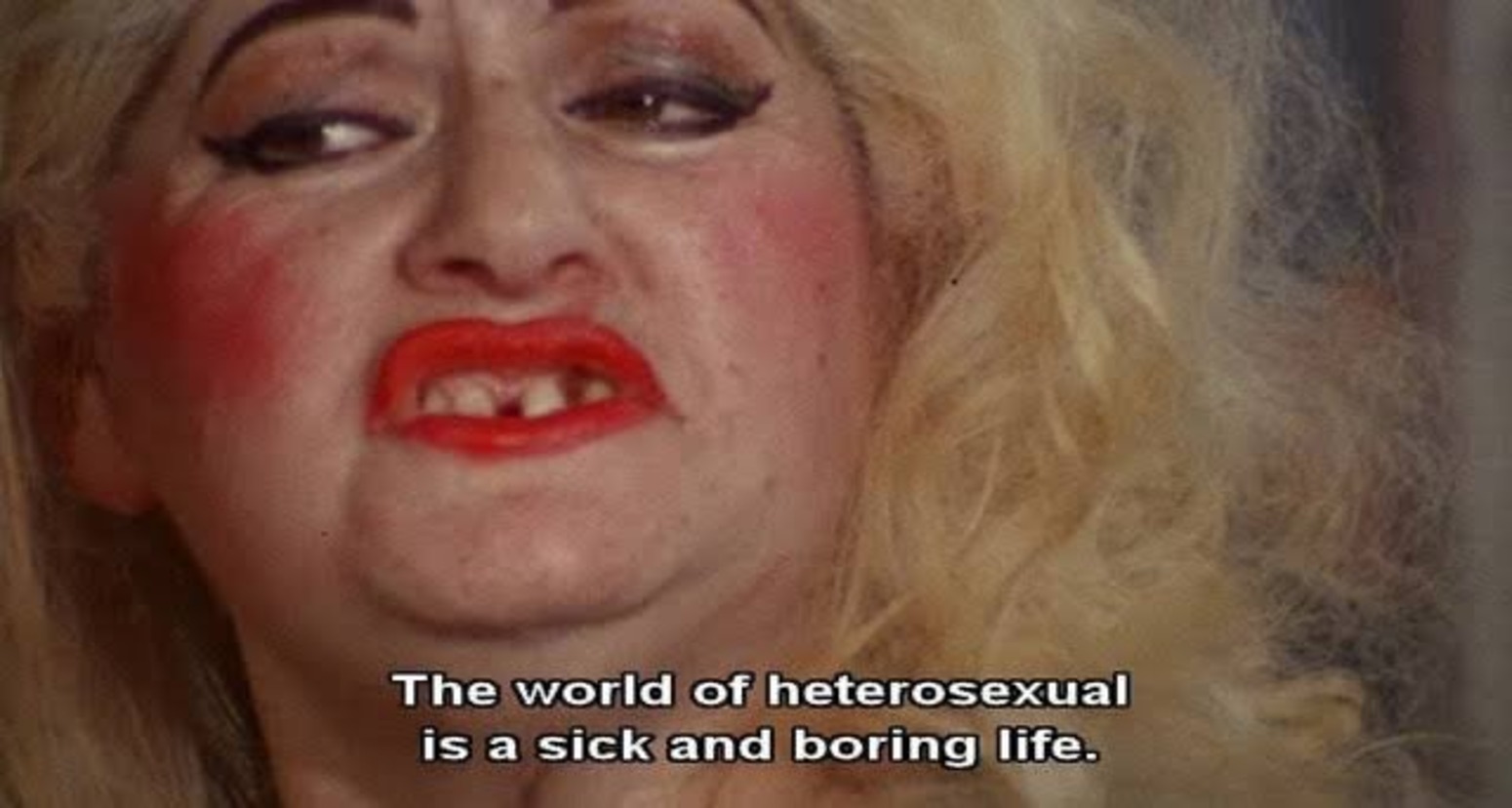

The term “heterosexuality is a prison” isn’t just a snappy internet witticism then, but a comparison that’s been used for decades. The formal concept of heterosexuality — that is the need to explicitly name the act of sexual intercourse and/or romantic connections with those of the opposite sex, has partial roots in eugenics, a faux science propagating that the “genetic quality” of the human race can be improved by discouraging or stopping those deemed inferior from reproducing. Many of them were surprisingly realistic about how unsatisfactory heterosexual marriage was for women, acknowledging that it was frequently a site of rape and domestic abuse, sexual shame and mutual dislike. Dr William Robinson, an American urologist and eugenicist said of heterosexual marriages, in his book Married Life and Happiness in 1922, “Have you observed the disillusionments, the heartaches, the disappointments? Have you measured the disgust, the indifference, the resentment, the mutual ill will… I assert and could readily prove that the lives of married couples, particularly married women, is not very different from, not much better than prison”.

For eugenicists this was a problem. They worried this dysfunctionality would be an impediment to white couples procreating and in their eyes refining the human race. As a result, a self-help approach to “fixing” heterosexuality was propagated; unsurprisingly instead of fixing the underlying issues to do with this fundamental unhappiness between men and women (i.e. dismantling patriarchy), they proposed women make exterior changes to be more enticing and simple management solutions to curbing men’s violence. By the mid 20th century, this self improvement was fully commodified, with women pressured into buying goods and services like stockings, make-up, or for women of colour skin lightening creams, that would seemingly shelter them from the violence and banality of men. Increasingly, marriage was seen as a “trap” for men, a massive curtailment of their natural instinct for freedom, and their only escape was forming homosocial relationships with other men who got to enjoy the love, respect and care that their wives, deemed as trivial, were not given.

I mention these neo-liberal self help solutions because they continue to haunt us today. Wildly popular books from the 90s such as Men Are from Mars Women Are from Venus posit an idea central to straight culture: that men and women are irreconcilably different, and the best you can do to solve this is to engage in extensive emotional compromises and subtle manipulation to get what you need. Steve Harvey’s Act Like a Lady, Think Like a Man encouraged women (especially Black women) to suppress being overly emotional, and to subtly manipulate men into wanting a relationship. Sex and the City encouraged us to view our female friends as our real soulmates. Social media algorithms reveal reams of content for straight women on discovering your attachment style, or how to identify a toxic narcissist, so you can presumably self-diagnose away your problems with men. Even today, media largely promotes understanding men in terms of personal pathology, rather than them being socialised and shaped by sociological forces like patriarchy and misogyny.

“I couldn’t be more grateful that I’m not straight,” says Jane Ward, a queer academic and author of The Tragedy of Heterosexuality. She’s adamant that contrary to the long-standing myth that being queer is to open yourself up to a life of misery, the romanticisation of heterosexuality masks “a whole other reality of the profound freedom and relief that many of us feel to not be in relationships with men.” Much of her book, in fact, is research from queer people about why they tend to avoid straight culture. “Queer people were observing misery and complaint, and the way straight women’s suffering was so distorted by straight culture, romanticised and turned into a playful joke, rather than addressed as the inequity and injustice that it is,” she says. Certainly, the romanticisation of women’s pain is considered almost a rite of passage for entering womanhood. The scaffolding of many female friendships is sharing “survival stories” as Jane calls them. It’s a badge of honour to have been resilient in the face of male cruelty.

A key piece of heteropessimism, Jane says, is the culture of complaint, the idea, often seen on TikTok, that lesbianism would be somehow easier. But still women are also capable of being highly complicit in the continuation of patriarchy (coined “patriarchal bargaining” by the Turkish academic Deniz Kandiyoti) for the purposes of small personal gains, even though it largely doesn’t serve them. For many of us, the physical security of having a man, and the status that gives, the sense of relief even that we are “on the right track in life”. The merit of being with a man, then, can be enough to accept the frequent miseries abounding straightness. “Straight women are absolutely complicit [in maintaining straight culture],” Jane says. “Those are the crumbs of heteropatriarchy and you’re scrambling for those crumbs.”

So is heterosexuality doomed? In its current form, juxtaposed against women’s increased ability to choose to opt out if men just aren’t meeting the mark, perhaps. But that visceral true desire many women have to be both sexually and romantically involved with men and vice versa, clearly isn’t going away. Perhaps straight women need to start by being willing to be brave, and eschew the false illusions of security and superiority, the mythology of straightness we too willingly buy into. And perhaps straight men need to realise that giving up their humanity, their ability to empathise and truly see women as people, to have truly meaningful romantic connections, isn’t really worth it in exchange for some free domestic labour and ownership of women. Like many women, I remain daunted by the scale of this task but I do remain hopeful that if a positive version of heterosexuality isn’t achievable for me personally, that I am not really missing out on much anyway.

As a remedy to our growing heteropessimism, Jane proposes a concept called “Deep Heterosexuality”, building on previous feminist, much of it lesbian feminist, concepts. “It ultimately feels a bit depoliticising and helpless as it’s based on resignation,” she says of our current flop era. “There’s so much more that straight people can be doing to revolutionise heterosexual desire. What does it mean to desire and be sexually attracted to someone who mirrors you as opposed to someone who is a mystery to you, or a risk to you?” I propose that straight men get to work by dis-identifying with the opposite attractive model, instead deeply investing in women.”