Stüssy’s official launch date is anything but concrete. Don Letts, the musician, filmmaker and OG-affiliate of the brand says it all started in 1984, but Shawn Stüssy first remembers scratching his infamous punky scrawl in 1979. Without an official logo, per se, Shawn was making surfboards and branding them with a signature scribble — a practice that, though he was unaware at the time, teemed with potential. He later applied it to T-shirts, earned cult acclaim, and a few years down the line, what is arguably the original streetwear brand was in business.

Underground culture was inherent to Shawn’s work, as was a William Burroughs-esque aptitude for combining scenes, ideas and tastes in simple, effortless clothing. Hip-hop, reggae, graffiti, surfing, skating, punk: a span of influences and urban cultures were brought together to create graphic-heavy garb, at a time when these influences weren’t as widely catered to. Before Stüssy, the youth were reinterpreting, borrowing and cutting garments up — or, in the case of those seeking out higher-brow attire, stealing Ralph Lauren Polo. Stüssy filled a void; his work reflected what people wanted to buy.

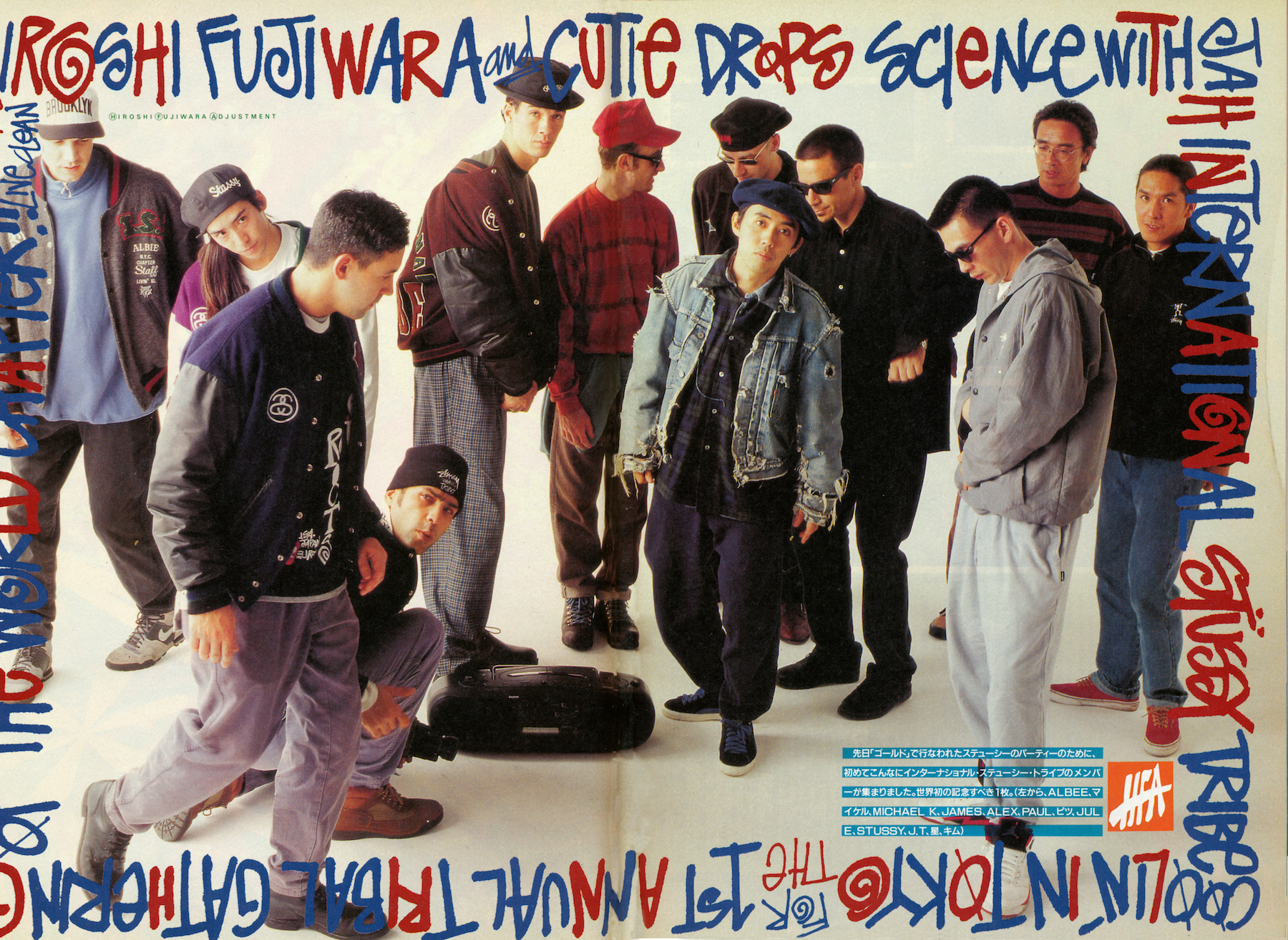

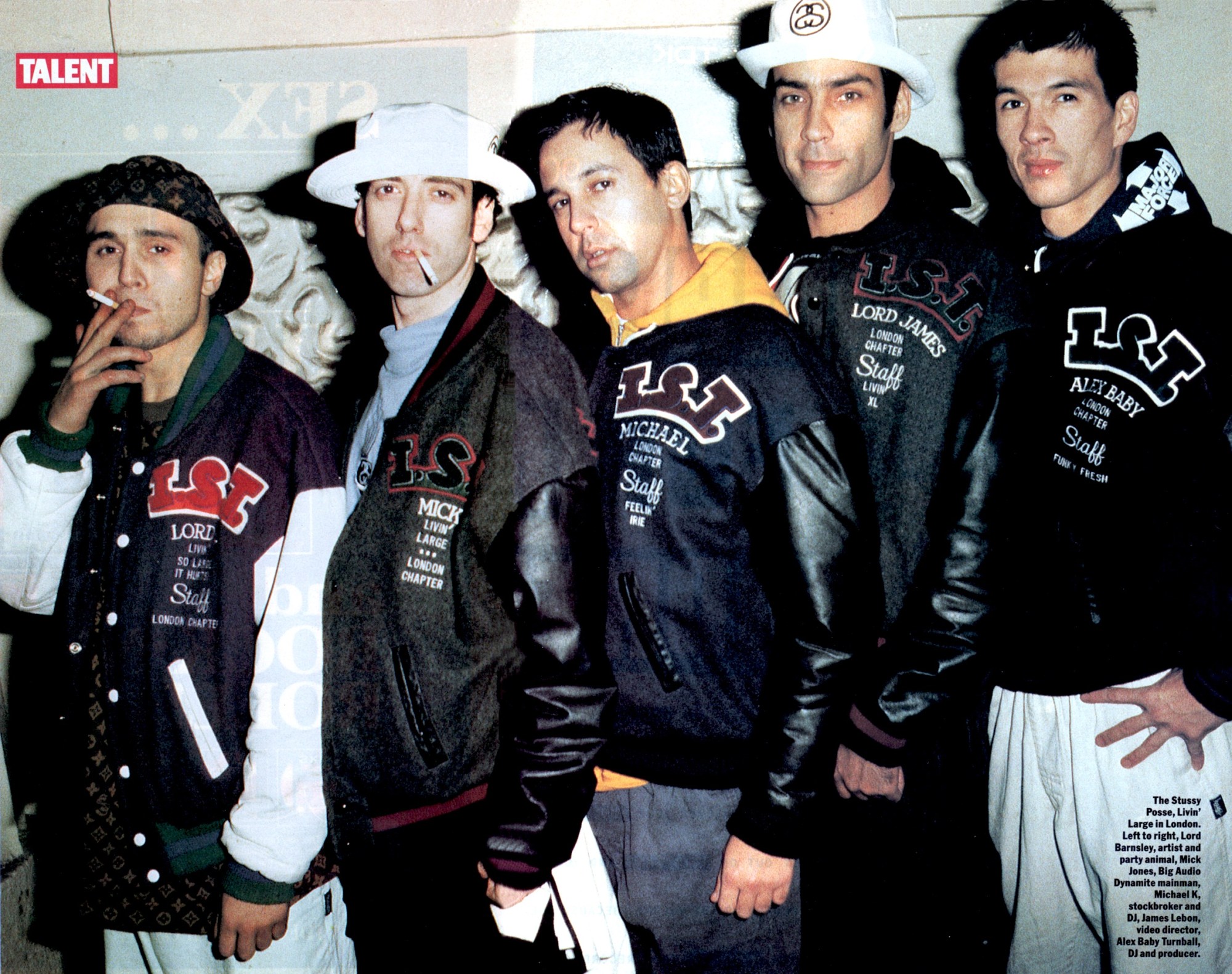

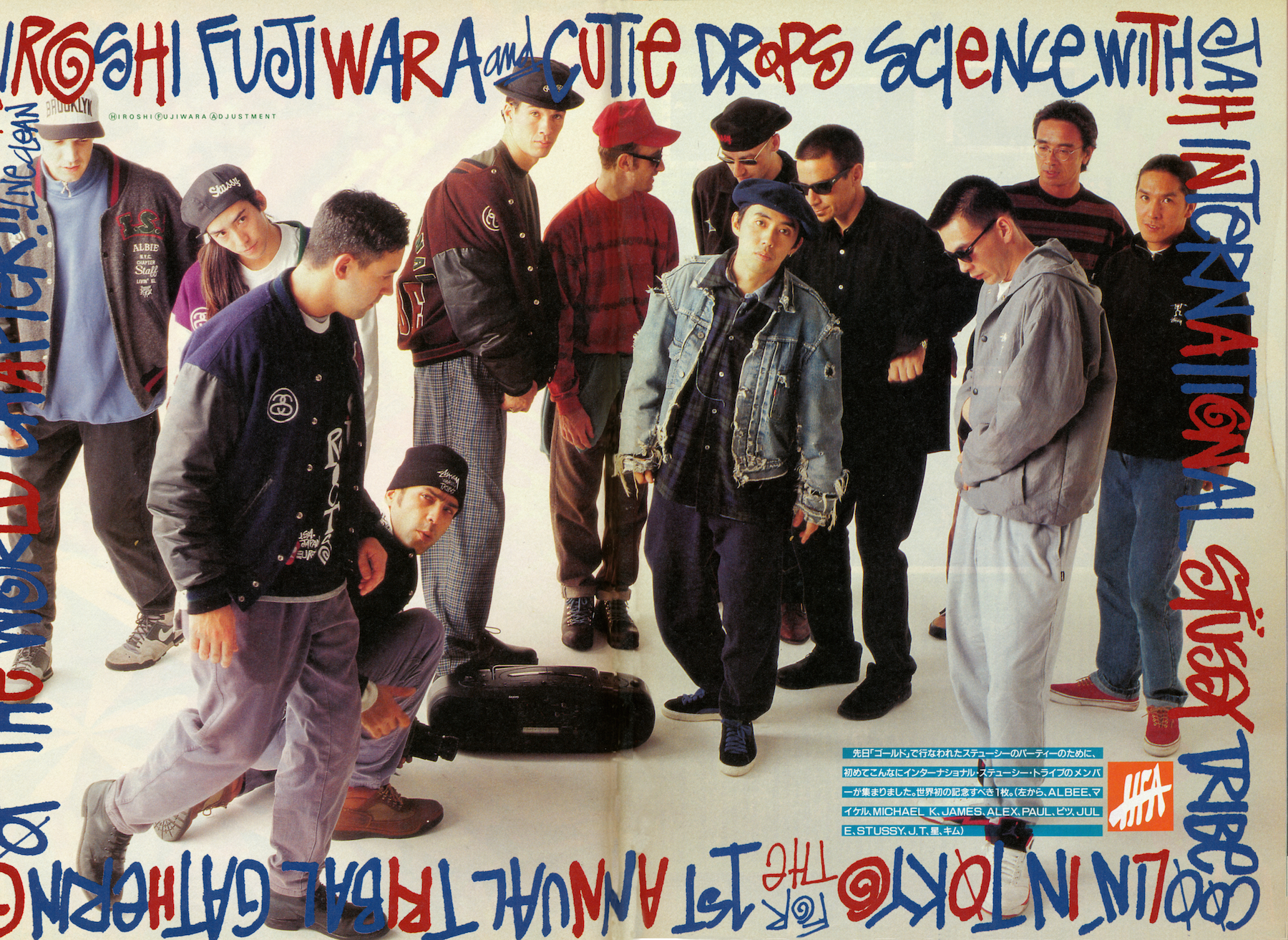

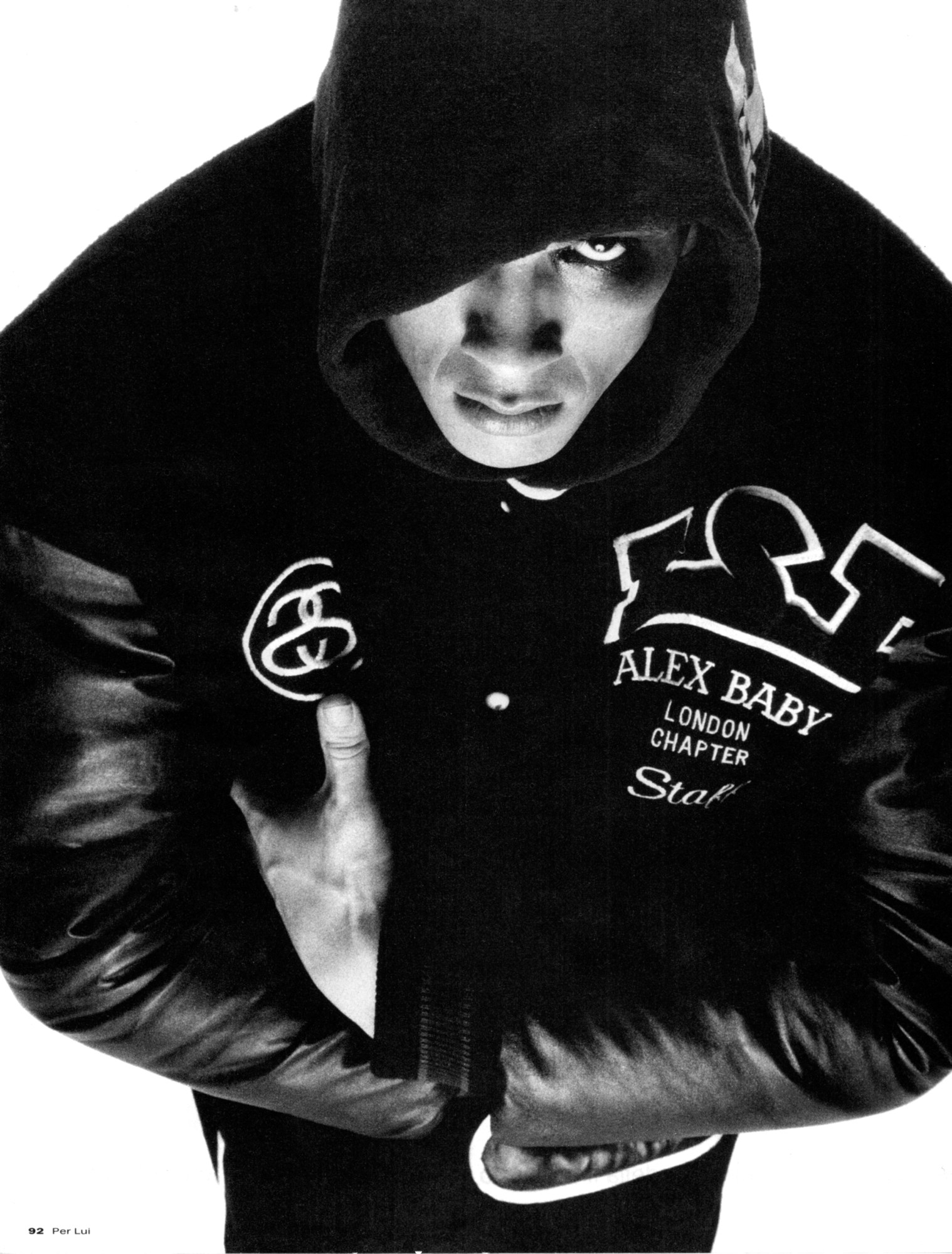

Shawn’s ideas developed organically, spurred on by the ever-expanding network of individuals he came across. “He just kept on meeting like-minded people that were interested in similar things,” Stüssy’s former creative director Paul Mittleman says. “It just kept on going.” The International Stüssy Tribe, a club founded by Shawn, was the beating heart of the brand. One of the original members, Alex Turnbull AKA Alex Baby, remembers the first time he and Shawn met. Originally from London, then a hip-hop DJ in New York, Alex was hanging out with Jules Gayton, a DJ and part-time assistant to Jean-Michel Basquiat. They were routinely flying between London and New York, shuttling rare record collections across the pond. On one visit, Paul invited them over to the Stüssy warehouse. “It was basically a couple of rails of clothes in a space for something else, and Paul was just sitting there,” says Alex. “I remember leaving with a T-shirt and a pair of the beach pants, and they were just mind-blowing.” Never before had he seen such hip-hop amenable clothing. Not long after, Shawn would make a visit to London, attend a nightclub Alex was playing, and initiate six or so members with the now-infamous tribe jackets, complete with logos, names on the front, and ‘Staff’ stitched on them. Not your average hiring process.

With time, the tribe grew. In London, there was hairdresser James Lebon, Gimme 5 founder Michael Kopelman, streetwear scenius Barnzley Armitage, The Clash’s Mick Jones, Big Audio Dynamite’s Don Letts, and jungle pioneer Goldie. In New York, skater Jeremy Henderson, hip-hop A&R rep Dante Ross. In LA, thrasher Tony Converse. Not to forget streetwear kingpin Hiroshi Fujiwara in Tokyo. It was a network of taste-makers, skate rats and musical vanguards, spread across what Alex considers the world’s most culturally adept cities. “With the exception of Kingston, Jamaica, of course,” he’s quick to note. Through his tribe, Shawn had innocently stumbled upon and mastered a communication method that a good proportion of brands are still eager to decode today. “Shawn even pre-empted the whole ‘viral’ thing, foregoing big budget advertising and trusting in the organic process of word of mouth,” Don Letts remarks.

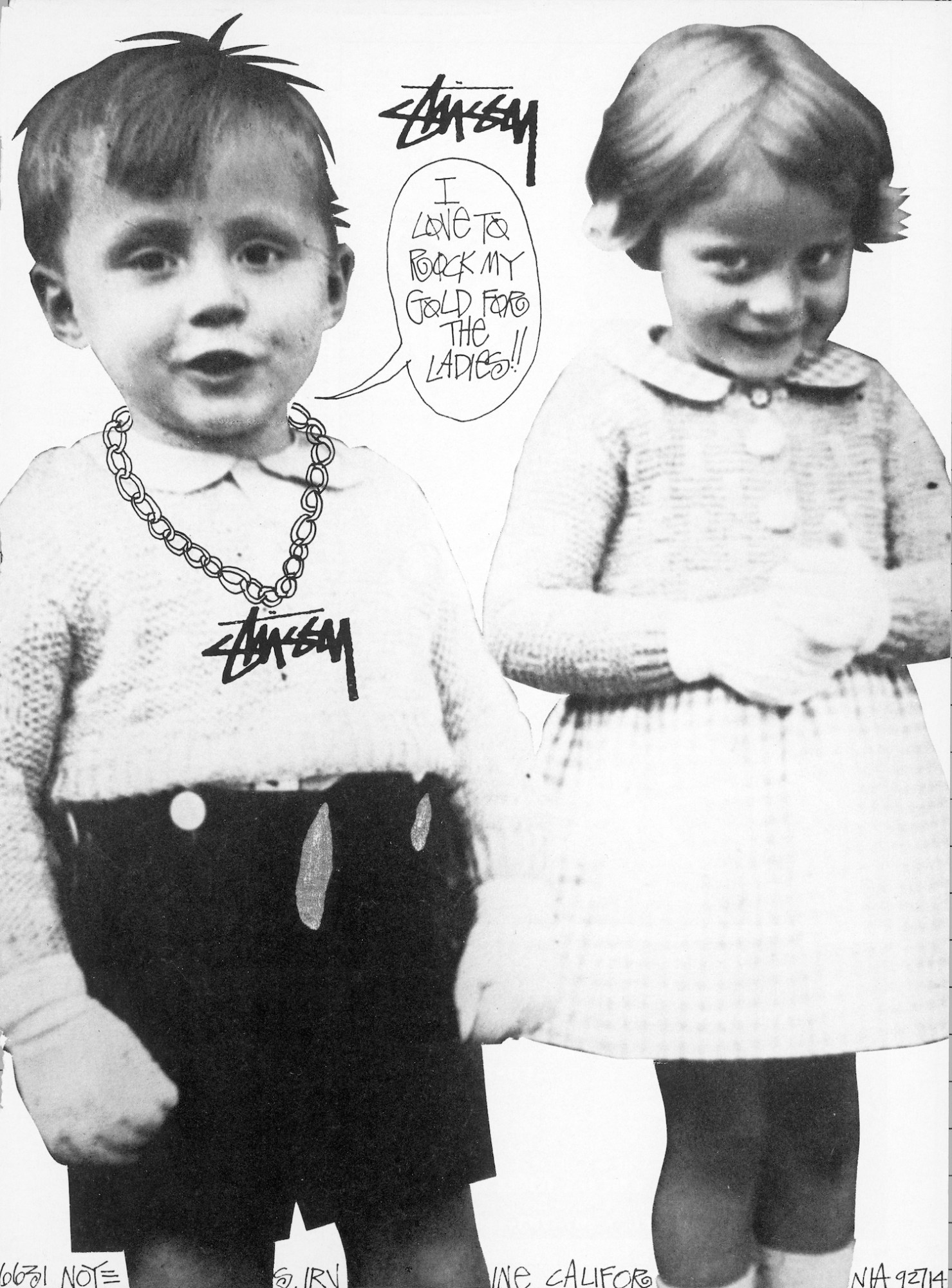

Profiling the brand in the 90s, BBC 4’s The Look interviewed Shawn, as well as some of his associates in an effort to unpick the fashion phenomenon. Shawn’s modest attempt to explain his craft was “pants and shirts… and jackets and hats.” But behind the brevity of his response lay a firm confidence; after all, his formula of quality over quantity had garnered enough interest to warrant a BBC feature. “A lot of people collect them — like these, there’s ten of them, and some people buy every single colour”, explains then-Stüssy’s store manager James Jebbia, pointing out the ‘S’ logo baseball caps. As you’ll likely know, he would later go on to found Supreme, streetwear’s eminent household name. And just as Stüssy had done before, sampling, ripping and re-appropriating became key components of the Supreme creative vocabulary. The former’s infamous interlocking Ss, a humorous ape of Chanel, would foreshadow the latter’s cease-and-desist Louis Vuitton rip skate decks. Looking back, it was oddly prescient, given that both would work with top-tier conglomerate fashion houses years down the line.

Paul draws a parallel between Shawn’s work and 80s postmodern art: just as Jeff Koons placed submerged basketballs in the gallery space, Shawn placed lyrics from American hip-hop duo EPMD on clothing. ‘I get goosebumps when the bass line thumps’, reads a now-coveted T-shirt. In introducing aesthetics and cultures deemed low-brow into public consciousness, Shawn’s graphic style also shared much with graffiti writing, which, as Alex is keen to note, was still considered mere vandalism at the time: “You were still a criminal, it wasn’t accepted as art,” he says. Regardless of public opinion, that confluence of cultures it implied made it widely wearable, as Dante Ross echoes: “We could wear it to a thugged-out party, to a trendy event or to go skate in, all depending on how we wore it.”

At a time when streetwear is unarguably ubiquitous, it’s easy to forget that streetwear was counterculture. “Without Shawn, there would be no streetwear”, says Ross Wilson, an acclaimed streetwear collector who sold a 1,000+ piece Supreme archive in 2018. “Shawn Stüssy is the reason I became immersed in this culture in the first place.” And it doesn’t seem like Stüssy’s contemporary relevance is in decline — if anything, the opposite is true. ALYX creative director Matthew Williams grew up a Stüssy fan, citing it as “the first fashion brand outside of huge sportswear brands that I became aware of.” He now regularly collaborates with Kim Jones at Dior, and his work featured alongside Shawn’s graphics in the house’s Pre-Fall 20 menswear collection. And then there’s Kim himself, who grew up working at Gimme 5, one of Stüssy’s first UK distributors. “He’s part of the community; he’s not just an observer,” Paul says.

While today the internet has allowed everyone, wherever they’re from, the opportunity to engage with street culture, things were trickier in the 80s. But despite the developments since, Stüssy has far from lost its lustre. If anything, the past decade has reiterated Stüssy’s position as a subcultural fixture. Whether throwing parties with Boiler Room or spotlighting Kiko Kostadinov, Stüssy has been – and still is – a driving force in contemporary culture and fashion. Nonetheless, its core values remain: quality clothing, radical graphics, and international community dedicated to representing the brand. As the network has expanded, it’s only grown stronger. The launch of Stüssy’s London Chapter store was a case in point: a BBQ attended by old disciples and a fresh batch of new ones. One of the newcomers to the brand, Jordan Vickors, is grateful for its illustrious history. “It’s been my home since the second I joined; everything Shawn, Alex, Goldie, Paul have built over the years has provided me with a hub of creativity and energy. I can’t thank them enough.” Indeed, as a print on a particularly iconic Stüssy T-shirt, referencing Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry”, reads: ‘In this great future, you can’t forget your past.’