Sometime in between the release of the first Beatles album, in 1963, and the election of Margaret Thatcher, in 1979, art changed forever. This is the period that the Tate Britain’s new exhibition, opening April 12, will explore. Conceptual Art simply turned trad art on its head, away from traditional forms of paintings and sculptures, towards ideas — influencing everything, from culture, pop music, fashion, and beyond.

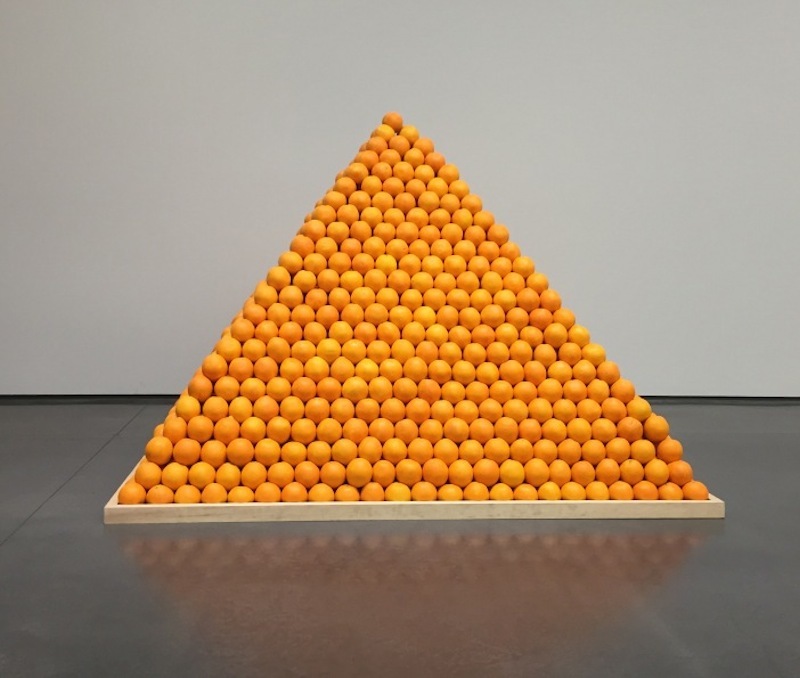

The idea became everything: from Roelouf Louw’s Soul City of 1967 — a pyramid of oranges the viewers were invited to take from (or not) — to Michael Craig Martin’s 1974 Oak Tree, a glass of a water and explanatory text. The conceptual art movement took in everyday objects, simple ideas, ready made sculptures, as a way of attacking both the structure of the art world and society itself.

Arguably beginning with Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain — a urinal the French artist signed “R.Mutt” and submitted to an open exhibition in New York in 1917. The open exhibition closed around it, denying Duchamp his place, but inadvertently opening up the history of art to all manner of experiments. Conceptual art spans from Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased De Kooning Drawing (which was, quite simply, a pencil drawing by Willem De Kooning that Robert Rauschenberg erased) to the whole oeuvre of, in different ways, Yves Klein and Sol LeWitt, and culminating in Britain with the YBAs, and Martin Creed winning the Turner Prize for The Lights Going On And Off, a totally empty room installed with a pair of flashing lights.

The history of conceptual art has never been free from controversy; in fact it’s been a lightning rod for it. Famously, in 1976, Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII was put on display at the Tate, creating an uproar in the press. The sculpture, 120 bricks arranged as a rectangle, was ridiculed as a con trick by the American artist on the British public; with Britain’s biggest gallery buying a pile of bricks. The work was vandalized with paint, but has grown to become one of the gallery’s most loved and infamous works.

This generation of artists rejected the post-war art world and recreated it. The conceptual artists — with relentless questioning and restless curiosity — pushed the possibilities of art into new places. It might’ve been met with mockery and incredulity at times, but the legacy can still be felt today.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

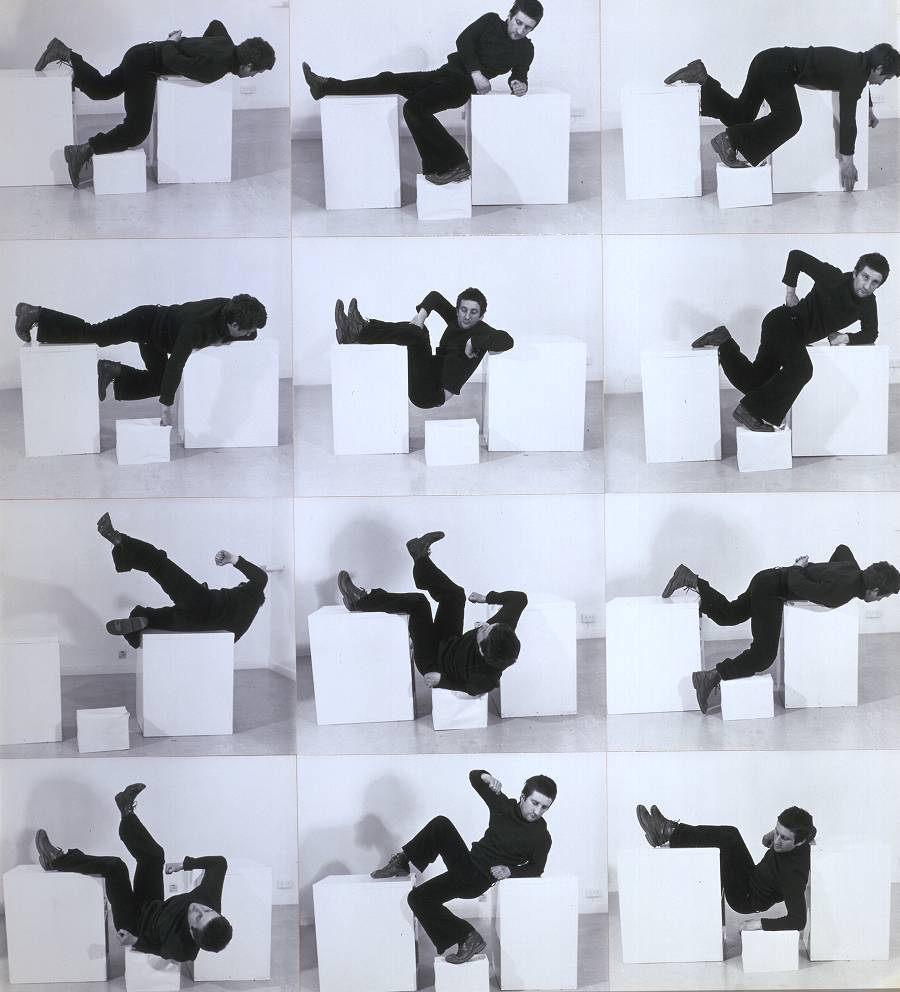

Main image Keith Arnatt, Trouser – Word Piece 1972-1989