Artisan, mentor and queen Judy Blame was one of those rare fashion figures whose dry wit and kindness were matched only by the breadth and depth of his work. His chosen practices – styling, art direction and jewellery design – questioned notions of value, provoked political thought and offered an antidote to mass consumption. A pivotal character in fashion history, his bricolage and playful dissection of iconography has achieved almost mythical status since his untimely passing two years ago. His legacy, however, lives on strong, influencing designers from Matty Bovan to Kim Jones at Dior.

Raised in the dreary English countryside, it wasn’t until the age of 17 that Judy Blame — then Christopher Barnes — dyed his hair orange and fucked off to London, forgivably uninspired by the tedium of rural life. The next day he was in Vivienne Westwood’s shop, Seditionaries, buying his first pair of bondage pants from Viv herself. London was home for only a week, though, before he headed north to Manchester’s Moss Side. There, he became a committed participant in punk, a style influence that can be traced throughout his work till the end. Having rubbed shoulders with the likes of graphic designers Peter Saville and Malcolm Garrett, Judy returned to London a year and a half later, armed with a little more cultural capital and, most importantly, an enduring desire to create.

![Judy Blame in i-D [THE MADNESS ISSUE, NO, 34, MARCH 1986]](https://i-d.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1582113340459-a-look-through-the-judy-blame-i-d-archive-body-image-1466095913.jpeg?quality=90&w=1200)

From his Charing Cross base, Judy moved in circles that defined the 80s. Feeling that punk had become too uniform, he and his cronies fell into the New Romantic scene, a subculture spawned in reaction to punk’s austere nihilism. Working in the gay club Heaven’s coat check, Judy built a network of friends that would follow him through the rest of his life. In an interview with Gregor Muir at the ICA, Judy recalled how the Heaven scene consisted mostly of leather men and clones, a gay tribe recognisable by their moustaches, flannel shirts and short hair. Though Judy’s desire to dress up sat at odds with these trends, he nonetheless found his own solution to the issue. “Judy and another friend of ours, Michael Hardy, were working the coat check. Somehow, they persuaded Heaven to let us have the back bar, which is where we held Cha-Cha on Tuesday nights,” says Scarlett Cannon, one of the maverick stylist’s closest friends. “He was like: ‘You’ve got to come on board with this. It’s going to be fabulous.’ That’s just how Judy was,” she adds.

Forty years down the line, Judy had collaborated with Comme des Garçons, Moschino and Louis Vuitton; all the while keeping one foot firmly in the underground. A collaborator to cult workwear wizard Christopher Nemeth, a champion and mentor of young designer Christopher Shannon and an inspiration to fashion design students the world over, Judy cut a fine balance, and therein lies his brilliance. One week could take Judy to Paris, consulting for John Galliano at Dior; the next would see him mudlarking along the banks of the Thames, collecting scrap metal and bones. These forgotten odds and ends would be reworked and collaged to create haute jewellery, proving that one man’s trash truly is another man’s treasure. This knack for breathing luxury into even the most banal of objects would eventually be recognised in a 2016 solo exhibition at the ICA, just two years before his untimely passing.

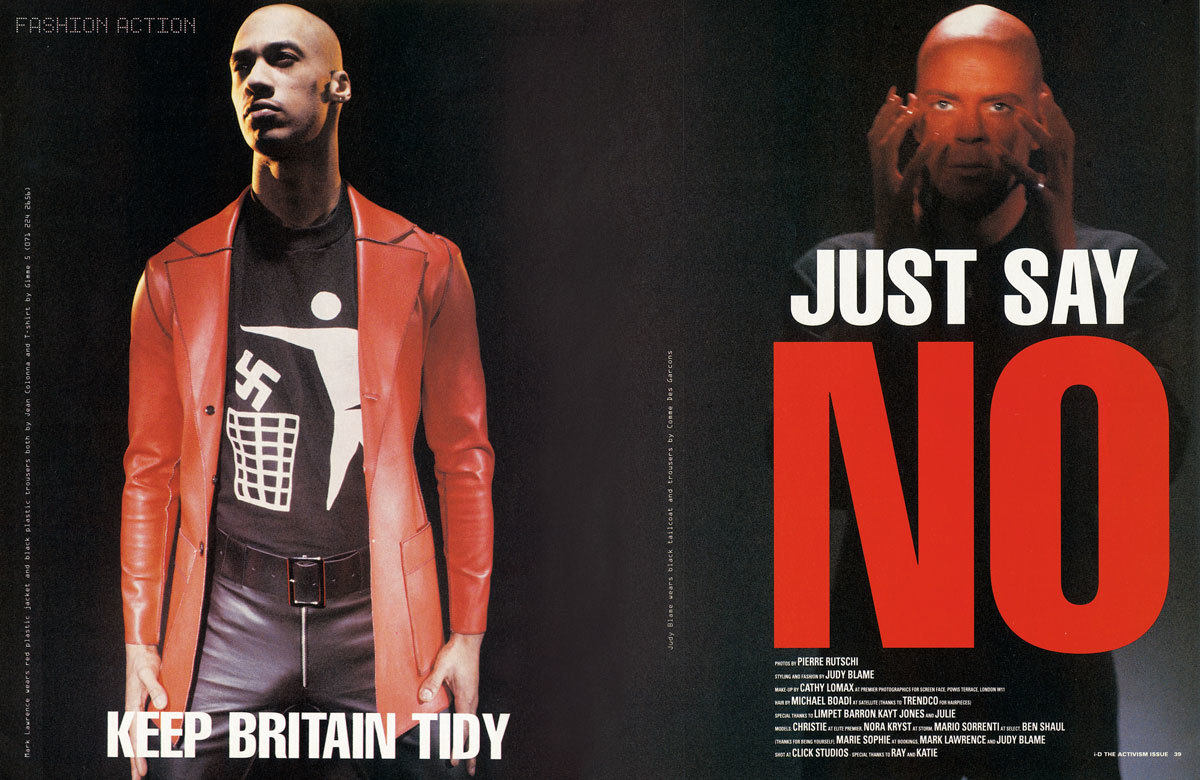

Attempting to pinpoint Judy’s job title sits at odds with everything that he was about. Long before styling was an established career path, let alone something you could formally study, Judy was banding friends together for editorials published in i-D, which remain seminally significant to this very day. “He played with semiotics, the messages were immediate, powerful and had urgency,” says Zoe Bedeaux, a former styling assistant to Judy. In one such series, then-model Alex Turnbull wears a full Burberry nova check get-up at a time when the brand was associated with football hooliganism; another features a leather two-piece and a witty anti-fascist ape of the ‘Keep Britain Tidy’ campaign. Masterful orchestration was key to his styling, but often his approach was totally improvised. “When you’re truly talented and creative, you can do that,” affirms photographer Mark Mattock. “And fuck did we have some laughs in the making. We held the record for the most beers consumed during a shoot,” recounts Mark of a particularly debauched editorial for Joyce magazine at Metro Studios.

Refusing definition, Blame straddled scenes and skills, remixing and challenging ideas; whether that was in a garish getup on the dancefloor of nightclub Taboo, or redefining luxury through making necklaces with buttplugs or dildos. His signature style drew as much on utilitarian workwear — Christopher Nemeth’s jackets created from postal bags, for example — as it did on the zesty, performative garb for which he and post-modern drag artist Leigh Bowery were known. “He could make himself equally comfortable working with Adidas, as he could doing a little commission for some grand dame somewhere,” Scarlett notes. It’s little wonder, then, that Kim Jones, during his time at Louis Vuitton, tapped Judy to work on jewellery for their AW15 collection. Such was their respect for one another that Kim, now Artistic Director of Menswear at Dior, dedicated his AW20 collection to Judy.

Despite his work for behemoth brands, his styling gigs for Kylie Minogue and Neneh Cherry, and his illustrious back catalog of editorials, Blame never succumbed to greed. Integrity, Scarlett explains, was what made Judy and is why he’ll be remembered for years to come. His work for Louis Vuitton might have been paid, but he’d happily help Christopher Shannon with a collection free of charge. “He lived in a rented flat when he died, never bought property or anything,” says Scarlett. “There were many times when he could have said ‘If I just do X, Y and Z, and sell it to X, Y and Z, I can make however much.’” Of course, he didn’t, which is what positions his work closer to art than to mere fashion commodity.

In the face of fashion’s sustainability crisis, Judy’s work feels particularly pertinent. Salvage fashion is back and designers are finding new ways to repurpose deadstock goods, disposed possessions and junk. Art School’s Eden Loweth cites Judy Blame as a key point of reference in building their and Tom Barratt’s brand, particularly his ability to bestow significance onto otherwise trivial objects: “His ideology of collecting and holding small things precious has often translated quite directly into some of our work, including our jewellery for SS20.” In this collection, artist Richard Porter’s clay sculptures hung from rope, referencing the items Art School had found in artist Derek Jarman’s garden. And this queer kinship goes full-circle: by way of a lovely coincidence, Jarman was a close friend of Judy’s and the pair would party together at New Romantic haunt, Blitz.

Never without a rope or trinkets in his hands, Judy was a craftsman through and through. Using safety pins, his signature buttons or even a novelty plastic shit, Judy always found ways to weave beauty into even the most mundane things. Perhaps that explains his adoration for John Skelton, a resolutely anti-fast fashion designer who shows during London Fashion Week. Skelton, whose collections are characterised by folkloric references and meticulous craftsmanship, sees a mutual quality in his and Judy’s work: the elevation of the homemade to luxury. “He likened his work to a cottage industry, which I think is a beautiful way of describing what we do, because it’s never going to be something mass-produced, and it’s made by hands in small places, not by big machinery in factories,” says Skelton. “We spoke a lot about the importance of making something yourself and always having a needle in your hand. It grounds you.”

Grounded, generous and blessed with a wicked sense of humour, Blame was always hunting for the next thing — not just in his own ideas but in other designers’ visions of beauty, too. Perhaps if he were here now he’d be looking at Charles Jeffrey, whose punky extravagance patches, slices and dices symbols of heritage and national identity into a queer mash-up of well-tailored gear. Or Matty Bovan, who inflects his work with a DIY attitude that can be traced back to Judy and his friends’ creations at the House of Beauty and Culture, a collective and shop he co-founded, stocking designers adept in handiwork. For Matty, part of Judy’s influence can be found in this tangible, by-whatever-means ethos. “The transformative element of Judy’s work is what made it become so impactful. Kids these days should be doing all this at home in their bedrooms,” he says.

Judy’s influence is present everywhere. “I was in Dubai recently and a young designer was mashing up luxury brand logos and showing it to me as if it was a fresh idea,” Zoe Bedeaux says. But the extent to which his legacy makes itself felt doesn’t make his absence any less painful. When asked what Judy was like, Scarlett’s response is simple but touching: “I want to say he was a sweetheart, but that doesn’t mean anything to anybody, does it?” For those inspired by Judy’s work, it means everything.