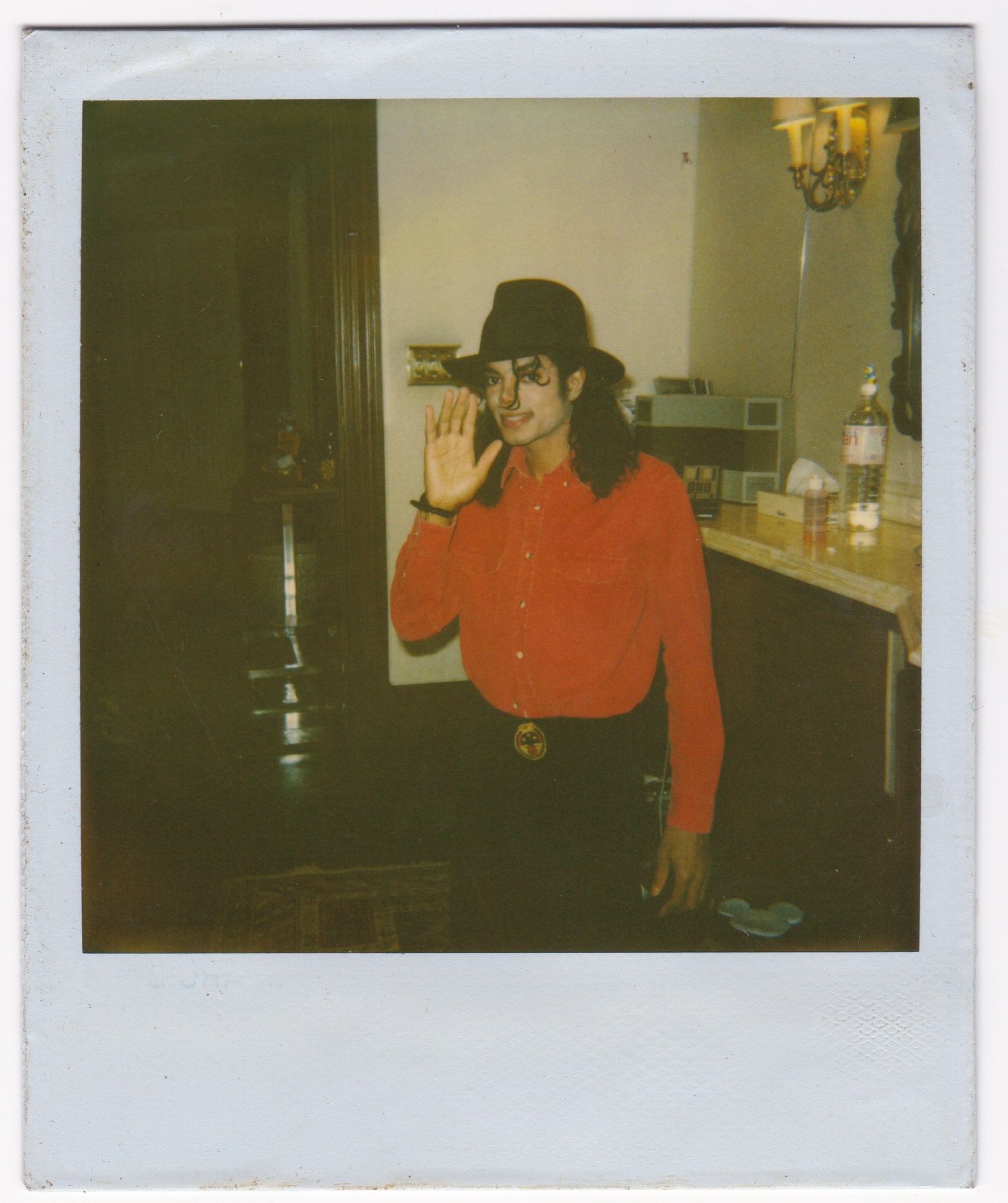

Michael Jackson was a master manipulator. Over the course of his career, up until his death in 2009 at the age of 50, he manipulated how people perceived him, be it through performance, plastic surgery or personality. Even when his life began to devolve into a freakish form of pageantry proffered up for public shock, derision and entertainment, Jackson still grasped the most powerful manipulation in his arsenal: his musical genius.

Manipulation isn’t necessarily a bad thing – we pay for directors and actors to manipulate our emotions when we see films, after all. But the usual idea of manipulation is more closely aligned with hubris, power and overbearing influence. It’s alleged that Harvey Weinstein manipulated many young women in Hollywood into sexual submission. R Kelly allegedly manipulated young women and girls into a “sex cult”, keeping them against their will and subjecting them to sexual, physical and emotional abuse. Both men deny the allegations against them. Jimmy Savile manipulated pretty much everyone he came into contact with into silence or solicitation with regards to his sexual misconduct with children.

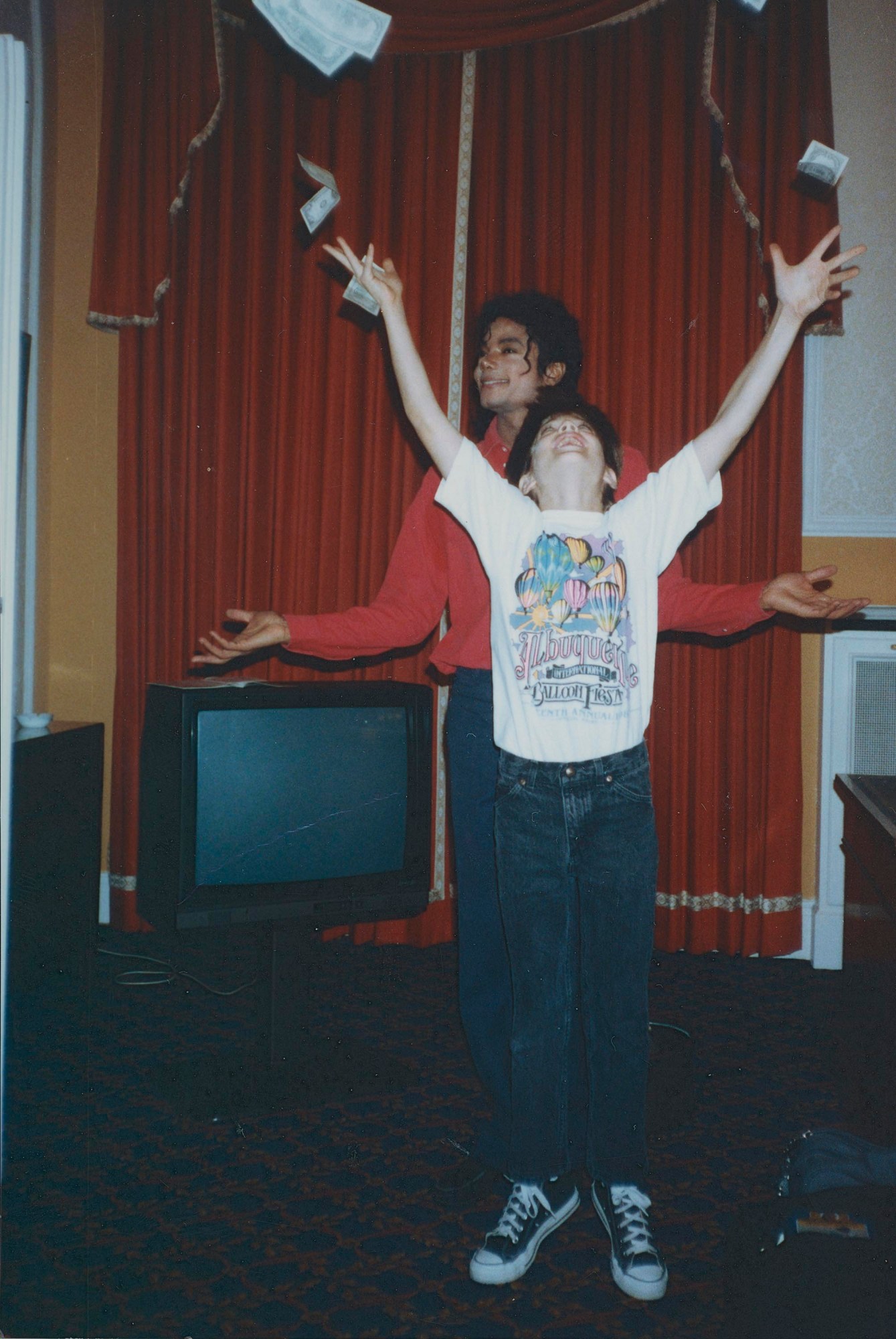

It’s this this kind of Savile-esque manipulation – the predatory and skilful manipulation of the strings of human behaviour and emotions – that is at the centre of a new two-part documentary film Leaving Neverland. In intense, excruciating and graphic detail, the film alleges how Michael Jackson, the seemingly expert manipulator, used his skills and celebrity to groom and sexually abuse two boys, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, in the 1980s and early 1990s. It’s been described as a reckoning for Jackson who, from 1993 up until his death, has been dogged by rumours and allegations of child molestation.

For many Jackson fans who discovered the singer in his post-imperial phase, myself included, our relationship with him is intrinsically linked with his eccentricities and scandals. We obsess not only over his creativity, but over his face, the construction of life behind the gates at the now infamous Neverland Ranch and, of course, the repeated accusations of child sexual abuse. In 1993, the singer was accused of molesting 13-year-old Jordan ‘Jordy’ Chandler. The case was settled out of court for a rumoured $20 million. Jackson was later accused again of child sexual abuse against Gavin Arvizo, a 13-year-old boy. The case went to trial and Jackson was acquitted of all charges.

Writing for the Los Angeles Times, critic Gerrick D. Kennedy spoke for many of us in his fandom when he said he’d “spent far more time than I can recall reading court documents, studying the allegations that trailed [Jackson]”. Personally, I’ve revisited the controversial 2003 Martin Bashir documentary Living With Michael Jackson more times than seems entirely healthy, analysing his behaviour for glimpses of genius, admissions of guilt and clues of depravity. The unwavering idolisation that I had of Jackson when I discovered his music as a child (the sort of idolisation that involved dressing up and imitating him incessantly), had mutated into a mixture of obsessional horror, fear and adulation in an attempt to uncover the truth about a man I knew I could never truly understand. His mystique created an inescapable circle of fascination.

Leaving Neverland, however, removes any speculative aspect about Michael Jackson and his relationship with children. The inconvenient truth presented in unflinching detail is that Jackson was most likely a paedophile who sexually abused young boys.

To be clear, Leaving Neverland is not a film about Jackson. It’s focus is two families and how the spectre of Jackson continues to haunts their lives. Both families — the Robsons and the Safechucks — tell of how the singer embedded himself in their lives. Both of them were child proteges — Wade Robson was an obsessive Jackson fan and talented dancer, while James Safechuck was acting in commercials. They describe how Jackson “anointed” them, with Safechuck, who starred in a Pepsi commercial with the singer, comparing his early meetings with the star to “an audition”.

The mothers in the film play an essential role. They were gatekeepers who Jackson charmed, so much so that one of them says he became like a surrogate child. He painted a portrait of himself as isolated and lonely, and these seemingly average people couldn’t believe that Michael Jackson, the biggest superstar the world has ever known, would want to spend time with them and offer their children opportunities that could forever change their lives.

Both families tell how Jackson would spend hours and hours on the phone with the mothers and children, turning up at their houses to enjoy the domesticity (Jackson also did this with Jordan Chandler’s family). Both Wade and James talk of how deeply in love with Jackson they were, but also how much they believed that the singer loved them in return. The way the film presents it, you can understand why the mothers allowed their children to be left alone with Michael. He was persuasive, loving, his relationships with children seemingly innocent. They would watch movies and eat popcorn, play with video games and have slumber parties. “It just didn’t seem that strange,” one of the mothers says.

Of course it was strange. In similar unflinching and harrowing detail, Robson and Safechuck recall how Jackson started to molest them when they were children. They both talk about how Jackson had an intricate alarm system that would alert those in his bedroom if people were approaching (this alarm system has been corroborated, specifically by the defence team in the 2005 trial brought against Jackson for child molestation).

Jackson also created rifts between the child and their parents, fostering an “us vs them” mentality. The parents in both families ended up separating, too, giving Jackson the chance to take on a paternal role for Robson and Safechuck; his attention provided solace from their disrupted home lives. He also threatened both boys, telling Robson that if he told anyone about what happened during their sleepovers that both of them would end up in prison for the rest of their lives. Safechuck recalls how Jackson used jewellery to bribe him into sexual acts, going as far to say that the pair had a mock wedding. But then that’s how these children say they viewed their relationships with the singer: it was a marriage.

However, marriages go sour. If Jackson is famous for anything it’s for his fixation with childhood, and the two men describe how they were replaced by younger boys. In fact, Jackson seemed to enjoy causing jealousy. Safechuck tells a disturbing story of how during one of his last sleepovers with Jackson, the singer got him drunk and then went off to the bedroom with another boy, leaving him distraught with envy. Robson also recalls how Jackson replaced him, opting to take Jordan Chandler on his 1992 World Tour, although he’d promised Robson the spot.

The conflicting feelings that both men feel about Michael Jackson make up the bulk of the documentary’s second part, as do the devastating implications that the abuse has had on them as adults. Both men also speak of nervous breakdowns, depressive episodes and fractured familial relationships. They share their anger at their mothers for allowing them to be put in that situation, while nursing the anger they’ve retained for themselves.

Still, it’s the stories told in this part of the film that have Michael Jackson’s legion of fans convinced that Robson and Safechuck have both fabricated their allegations. At the time of writing, those people haven’t seen the documentary and therefore haven’t seen how compelling and convincing both men’s testimony is. They also don’t seem to understand that for legal reasons neither Safechuck and Robson had heard the other’s accounts before watching Leaving Neverland.

But it doesn’t matter. Like conspiracy hounds, fans have built websites and created YouTube videos to undermine the men’s accounts. Robson especially has come under attack given that he testified in Jackson’s favour during the 2005 child molestation trial, denying that he was molested. There are also the two dismissed lawsuits that both Safechuck and Robson, who had asked for $1.5 billion in compensation, brought against the Jackson Estate in 2017. The Jackson Estate has come out strongly against the film, and are suing HBO for $100m (£77m), and in the complaint filed they state: “Michael Jackson is innocent. Period.”

What the fans and the Jackson Estate fail to understand is the impact that child sexual abuse can have on survivors when they reach adulthood. Safechuck and Robson talk about the fear they still feel today, as well as the guilt, shame and isolation that they experience.

Most pertinent, though, and what perhaps makes this case so singular, is the affection that both men and their families bestowed upon Jackson for years after the abuse ended. They describe how in 1993, when Jackson asked them both to deny that there had been any impropriety, they felt flushes of their love for him re-emerge. Indeed, you get the sense that Robson still struggles with the dichotomy between his love and anger at the man. “I understand that it’s really hard [for fans] to believe,” he said during a Q&A after the film’s premiere at Sundance. “In a way, I was in the same position that they are. Even though it happened to me, I still couldn’t believe that what Michael did was a bad thing.”

Cancel culture dictates that following such explicit allegations, the music of Michael Jackson should be locked away and discarded. But cancelling Michael Jackson is not the goal of Leaving Neverland, and it’s unlikely this film will be his kryptonite. Rather, the film’s focus is on giving two abuse survivors a platform to share their truth while exposing and challenging structures and behaviours that facilitate the sexual abuse of children. It made me think back to myself at seven years old – the same age that Robson was when he was first molested – and how I would have done anything Jackson asked of me.

I feel sadness for that little boy, just as I feel remorseful and devastated for those boys who did come into contact with Jackson. For years I had defended the man with the loss of his childhood and his treatment at the hands of the media. When he was acquitted of all counts of child molestation in 2005, I arrived at the conclusion that while sharing his bed and holding hands with prepubescent boys was inappropriate, there was no sexual aspect. Selfishly appeased, I went on celebrating a man whom I had worshiped since the age of five.

Even now while writing this article, after watching Leaving Neverland and spending days researching the most heinous abuse he allegedly inflicted on children, I cannot help but feel inexplicably and macabrely drawn to his music. Now, though, the desire is tainted and the compulsion leaves me feeling dirty. Yet still, the cycle of fascination repeats; his spectre remains. Perhaps no matter what happens, Michael Jackson will always continue to manipulate us.

Leaving Neverland airs on channel 4 on the 6th and 7th of March.