Legendary model and muse Pattie Boyd never wanted to be famous, but fate had other plans for the charismatic blonde who was at the forefront of a revolution in fashion, music, and pop culture during the 1960s and ‘70s. “I don’t understand why people want to be so public; they just need mystery to me,” says Pattie, whose beauty and charm inspired men to pen songs of love and devotion in her honour. Blessed with the perfect aesthetic blend of innocence and knowing, Pattie was the girl next door in a psychedelic age, combining the ethereal glamour of the 1940s with the elegant insouciance of the Sexual Revolution to create a style that could best be described as subversive chic.

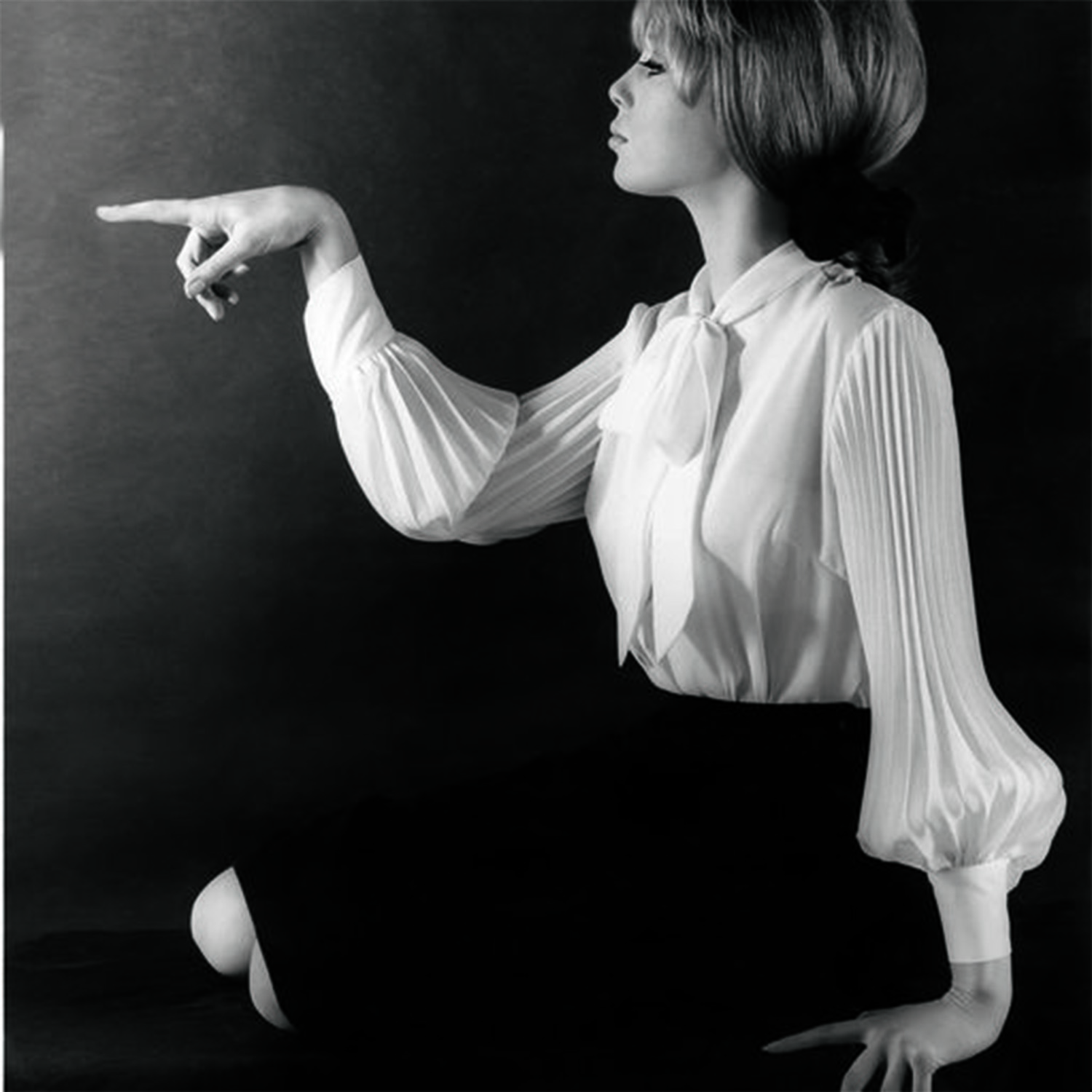

The girl with kaleidoscope eyes, gazing out at the world from the cover of Vogue magazine, Pattie looks back at her extraordinary life in the new book, Pattie Boyd: My Life in Pictures. Speaking from her home in London, Pattie, now 78, is possessed with warmth, wisdom, and wit, her lyrical voice as quietly captivating as the photographs themselves, which trace her journey on both sides of the camera as both artist and muse.

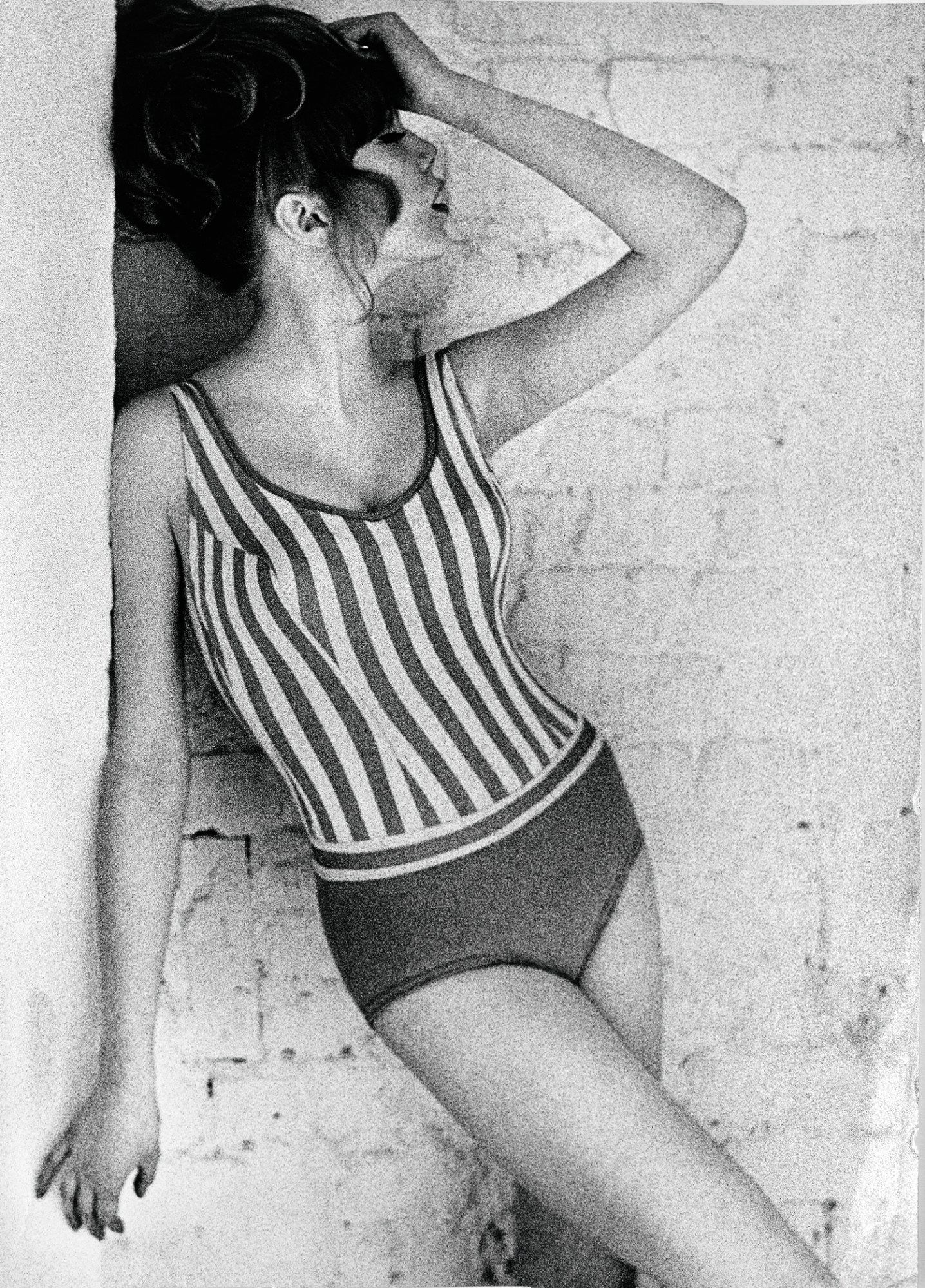

Pattie began her career as a model exactly 60 years ago, back at a time “when girls emulated their mothers.” The conservative styles of the 1950s, which relied heavily into bourgeois gender roles, still dominated the public sphere. Teens wore the same gowns as middle-aged women, looking hopelessly démodé. But as the austere years following the war finally began to fade away, a youthquake erupted across the UK. Standing at the vanguard, Pattie and a new squadron of models broke the mould.

“I remember looking at Vogue for the very first time and was astonished at the beauty and glamour. I wanted to be Jean Shrimpton,” says Pattie, who crafted her own look one that would become the inspiration for an entire generation including fellow icon Twiggy during the 1960s. “All the girls of my age during that period influenced each other in a very subtle way and we all had our own individuality, so it was a mishmash of personalities.”

As the winds of Women’s Liberation swept through the air, the emergence of women in high profile careers signalled a cultural shift that would form the foundation for a new era ahead. It was a far cry from how Pattie was raised. “We were brought up to marry well and that would be it,” she says of her years in Catholic boarding school. “I knew that I didn’t want to get married; my mother was married twice and it didn’t work.”

Securing a job meant income — and money financed independence. As Pattie made her way into the world of high fashion, she realised many publications were stuck in the old ways. This quickly changed as Pattie and her contemporaries helped advance the styles of the times by doing their own make up — and since there were no makeup artists on staff, their innovative looks soon became trends. Fashion designer Mary Quant noted that women would rather “look like Pattie Boyd rather than Marlene Dietrich”. Working with some of the greatest photographers of the 20th century, including David Bailey, Terence Donovan, Norman Parkinson, David Hurn and Robert Whitaker, Pattie was poised to usher in the radical transformations that began with the birth of swinging London in the mid-60s.

Pattie went from interview to interview with her portfolio, constantly meeting casting agents. She appeared in 1964 TV commercial or Smith’s crisps, and soon thereafter cast in The Beatles’ first film, A Hard Day’s Night. Although the notion of becoming an actress held no particular appeal, a certain lead guitarist did. Pattie began dating George Harrison and the two married in 1966, just as the band started to break out of their pop star packaging and explore Eastern mysticism.

Being an insider, Pattie saw the change to The Beatles, like that of music, fashion, and pop culture writ large part of a larger, gradual shift lead by a new generation that preferred to cast their own path rather than follow in someone else’s footsteps. Despite her proximity to the Beatles’ fame, Pattie maintained her identity, going so far as to keep her own name when such things were far from commonplace, and in doing so helped George understand equality in both practice and word. Pattie also began exploring her artistic side after moving into Kinfauns, her first home with George. They moved to Esher, Surrey, to escape the maddening crowds of central London, but the white suburban bungalow was “hideous, just ghastly,” she recalls.

“I don’t know what got into us but we bought all these tins of paint, brushes, and spray paint cans, and started painting the outside of the house,” she says. “In those days, we didn’t have any mobile phones so friends would just drop by when they felt like it. Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull came by one day, saw the tins of paint, and painted on the house with us. The press made up a story that The Rolling Stones didn’t like The Beatles, trying to make everyone competitive and choose which band they preferred but in reality they were all friends.”

Inside the psychedelic bungalow, Pattie began to explore a love for being on the other side of the camera, a practice she has maintained for decades. “When I was modelling, I was riveted by the photographers and what they saw, and how it was different for me standing in front,” she remembers. “I didn’t really know what they were seeing so when I bought my own camera, they would show me what I should be looking for. I wanted to capture what I saw, like someone who was unaware of how lovely they looked. The light might be playing on their face in a certain way that I found enchanting. I found it so exciting that I would hold my breath. I didn’t want this image to go away until I captured it.”

Pattie had the same impact on the men in her life. Inspired by his wife’s beauty, George penned the 1969 song, “Something,” which Frank Sinatra described as “the greatest love song of the past 50 years.” But George wasn’t the only rock star in love with his wife. One year later, his close friend and collaborator Eric Clapton would pen a song of his own, “Layla,” proclaiming his love for Pattie and creating a love triangle that held the public entranced.

“I remember Eric phoning me one morning, saying that they were just back from Miami where they had been recording and to come over to hear some of what they had been doing,” says Pattie. “I went to the flat his band was renting and Eric played me ‘Layla’. My first thought was, ‘Oh my god, this is so emotional and so passionate.’ And then I realised it was about me, and my fear was that George would hear it and realise Eric likes me more than he should.”

And though Eric begged, Pattie was unmoved until her marriage to George came to an end in the mid-70s. Clapton would continue looking to Pattie as a muse, writing “Wonderful Tonight” in 1976, “Golden Ring” in 1978, and “The Shape You’re In” in 1983. The two married in 1979 and divorced a decade later. But during their time together, Pattie’s creativity continued to bloom, as she collaborated with Eric on his album art. “We used to work on his album covers together, which was really fun because we were free to do what we wanted,” she says. “It was great fun working with him and I loved taking photographs. I thought he was so gorgeous but he used to get seriously fed up with me always with a camera in and pointing at him.”

For A Life in Pictures, Pattie seamlessly blends these public and the private sides of her life. The result is a mesmerising mélange of personal and professional memories that chronicle an era of style and stardom that elevated sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll to the pantheon of pop culture. Looking back at the trajectory of her trailblazing life, Pattie observes, “I’ve always been very insecure but I learned to be independent, and that means you have to keep striding ahead. I instinctively knew I would find my passion and that would guide me throughout my life. No matter who I was married to or whatever the way the wind was going to blow me I would still have something that would be only mine.”

Credits

Images courtesy of Patti Boyd Archive, Marilyn Stafford, Nancy Sandys Walker and Chris Floyd.