When I first saw the video for Coldplay’s “Hymn for the Weekend,” it was hard to choose what to be offended by first. The blatant tokenization of Indian culture to use as the backdrop for Chris Martin’s grandiose lyrics? Maybe the “noble savage” motif of the Brahmin priests, their orange shawls flowing in the mystical breeze behind them? Beyoncé’s hennaed hands and imitation Indian dancing? Perhaps it was the irritating trope of slum children running out cheerfully throwing colorful powder at each other as if everyday was holi? All of these things are demonstrative of a white gaze that carelessly glosses over the complexity of Indian culture in its hurry to construct a magical, mystical place that doesn’t exist.

The internet loves to talk about cultural appropriation, specifically the impact of white cultures appropriating aspects of marginalized ones as symbols of “cool.” Before Coldplay and Beyonce fetishized another community for a primarily white market, Katy Perry had made a habit of it: picking and mixing from geisha history, the African American community, and ancient Egyptian culture across various videos and performances. Prior to the term cultural appropriation even being popularized, Gwen Stefani was parading around wearing a bindi and making us cringe with her team of Japanese plus ones.

Even more so than music, fashion is perhaps the most fertile battleground for these debates. We’ve seen designers from Valentino to Junya Watanabe criticized for tokenization. The familiar response from designer is to explain they were simply drawing inspiration, then comes the critical response: their collections fail to meaningfully engage with this cultures which inspired them. Here lies the problem with taking influence from a culture that isn’t your own: how do we balance the harms of cultural appropriation against harmless intentions?

One could argue that Beyoncé donning a sari and waving her hands in front of her face for about 60 seconds didn’t cause any actual harm. You could even argue that being African American, Beyoncé can’t be guilty of cultural appropriation, because of the specific politics of anti-black racism, and colonialism. But Beyoncé’s failing, at heart, was neglecting to do more than window-shop an Indian culture.

But watching that video as a young Indian woman — and knowing Beyoncé’s background — didn’t stop me feeling uncomfortable seeing her in a sari. In fact, seeing any non-Indian woman wearing traditional Indian clothes, and benefiting from the use of our cultural heritage, juxtaposes uncomfortably with the experience I’ve had.

Katy Perry’s performance at the 2013 American Music Awards is a case study on how not to engage with a culture that’s not your own.

Growing up I was regularly teased and bullied for wearing traditional Indian clothing. To see Beyoncé, Gwen Stefani, or any number of random white women on the street wearing those same outfits or accessories as novelty is a slap in the face. You see; they can choose to take off the costume, and return to their daily lives when they want. I am unable to not inhabit the inherent Indianness of my appearance. No one wants to engage with the parts of a culture that aren’t cute outfit options.

By now, most of us have come to understand how appropriation is alienating to the people it references. It takes artifacts from marginalized groups and benefits from them—mimicking the original patterns of colonization and then laughing it off as flattery.

Appreciation is a trickier concept, but one I believe does exist on the scale of engaging with other communities. The only way to really define whether cultural appropriation is harmful is to interrogate the intent of the artist.

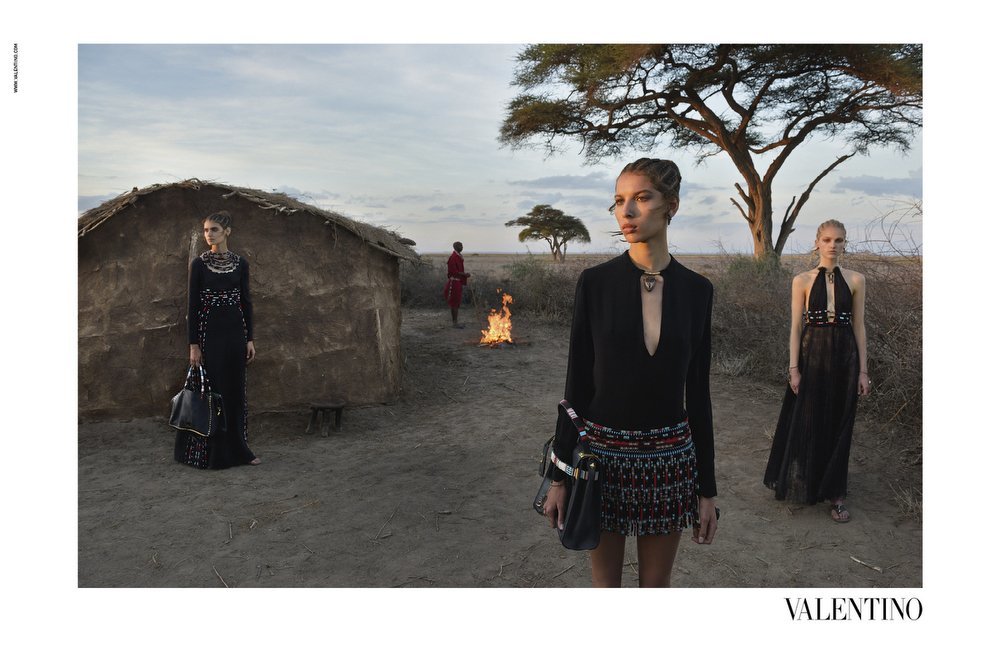

Let’s look at another, contrasting example: Valentino’s African inspired spring/summer 2016 collection and following campaign. When designers Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli were criticized for their use of bone necklaces, beading, feathers and cornrows, they were able to clearly detail their intention. They were attempting to engage with something beyond aesthetics: they were trying to explore cross-cultural influences in a time of increased migration, primarily from African countries.

The final product may remain problematic, as the show cast predominantly white models and homogenized the multitudes of cultures within the continent into one look, but their intent was to make a broader point — perhaps saving the collection being condemned entirely.

After all, when done well, taste for other cultures has its advantages. India actively promoted yoga to westerners in the 60s, sending practitioners on tours to the UK, and turning the tradition into an enterprise that was mutually beneficial. Westerners got yoga, Indian teachers got paid.

When discerning between harmful cultural appropriation, and the oft-problematic, but well-intended cultural appreciation, we look at engagement. That is, whether the group in question are willing participants in the exchange of ideas. Hermés demonstrated how this could work in 2011 when they released a collection of saris that were designed in collaboration with Kolkata-based designer, Sunita Kumar. The brand used the partnership as a chance to learn from individuals who identify with the culture and respectfully engaging with it through artistic expression.

Regardless of where you sit on the cultural appropriation vs appreciation debate, the take away lesson is to acknowledge that traditional clothing is about more than materials and outfit choices for culturally diverse people. They’re part of their history, community, identity and language. It might be made of fabric, but it’s so much more than fashion.

Credits

Text Zoya Patel

Images via Twitter