Last week, a 1 Granary talk with fashion lawyer Hugh Devlin at Alexander McQueen’s Sarabande Foundation revealed the vulnerable position of the fashion designer in our legal system. After Raf Simons’s departure at Dior, fashion media observed the ever-accelerating pace of the industry and the unstable position of the fashion designer at luxury houses. The conversation moved on eventually, but too little was said at the time about how this issue doesn’t just touch those at the top, it affects creators at any level — from the creative director to their design interns. The fashion designer, so it seems, is the least protected player in our system.

Being a young, independent designer in today’s corporate industry is undoubtedly arduous, and it seems to be only getting harder for a designer to survive today. Designers are essential to the industry, yet they are particularly unprotected by the law compared to other professions, whether that is concerning intellectual property, copyright, or employability. In addition to this, fashion design students are badly equipped when it comes to understanding the legal world that might help them.

“The most common mistakes that designers make when starting a brand is to assume that everyone is going to behave well. Get everything in writing,” Hugh Devlin, a leading fashion lawyer, told an audience of young fashion designers last week. The fashion law expert was invited by 1 Granary at Sarabande: the Lee Alexander McQueen Foundation (an organization financed by the designer’s estate to fund young and independent creativity), hoping to provide a helping hand to emerging designers. The overall atmosphere was bleak, to say the least, as Hugh explained that independent fashion designers are among those least protected by our legal system.

In the EU (before Brexit is enforced), unregistered design rights are automatically valid for a period of two years. But, this is not true for every country and does not apply in the USA.

The reality is that designers have to do as much as they can to protect themselves by way of contract, because even when the law is on their side, it is generally too expensive to enforce it. Therefore, designers do not always benefit from the protection that they are legally afforded. Without resources, it is nearly impossible to combat a big corporation or company. However, it is important not to get stuck in a bubble when difficult situations arise and recognize the position of designers in a commercial work environment.

Many conversations with fashion students and young designers land on the subject of protecting an individual’s creations, contracts with companies, and designers’ rights. However, these topics are rarely discussed within art education, or even in the fashion media.

What designers are aware of is the value of their creative power (or intellectual property). But how do you protect it? Very often, designers will not know what falls under those terms. Intellectual Property can mean a number of different things, which is the reason why terminology becomes so important. Hugh Devlin exclaims, “Never sign a thing you do not completely understand!” Copyright is the legal right to an artistic work. The moment something is sketched or made, the creator owns the rights to that piece of work. However, proving that something is yours is not always easy. In the EU (before Brexit is enforced), unregistered design rights are automatically valid for a period of two years. But, this is not true for every country and does not apply in the US.

One way to ensure protection is by registering a trademark. But, those are difficult to get and expensive. The registration can take up to two years, by the end of which the relevance of your creation will most likely be long over. “In fashion,” Hugh remarked, “the average shelf life of a product is equivalent to a banana.” On top of this, registering has to be done separately in every country. In short, if you do not have any financial power, you can forget about ever assuring full protection of your designs and even if you do, actually suing a person or a company for stealing your ideas, designs or creations costs money and time, something most young designers do not have.

Online call-out culture can provide a form of protest, but here again, big corporations have the upper hand. Scream too loudly, and a designer can be sued for defamation.

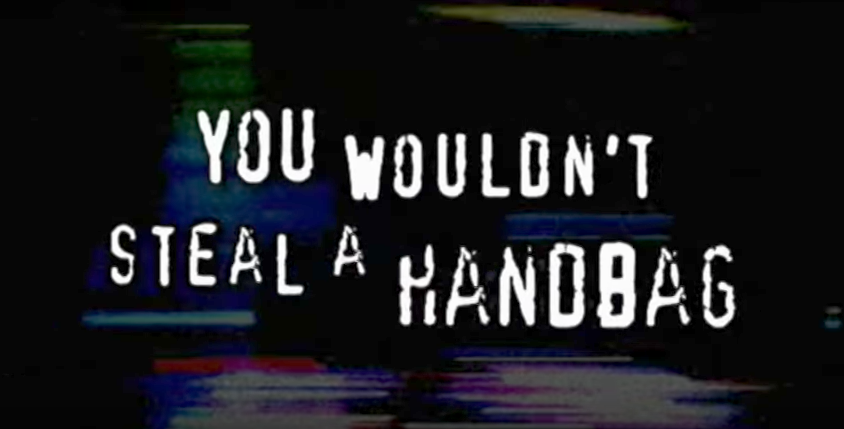

Fashion is a form of art that thrives on inspiration and appropriation. Where does the difference between being influenced by another artist and straight up stealing their ideas lie? Legally, the answer doesn’t favor original creation. Devlin is skeptical as well: “The problem is that you are designing for someone with arms, legs, and a torso, and there is only so much you can do to make it original.”

Online call-out culture can provide a form of protest, but here again, big corporations have the upper hand. Scream too loudly, and a designer can be sued for defamation. Publishing two images side-to-side can be effective, as it does not state a personal opinion, but rather becomes a way of drawing comparisons — simply by showing facts without bias. Or take an Instagram accounts like @dietprada, who use the power of anonymity to effectively call out instances of outright copying.

In order to prevent these situations, big companies started hiring designers for the right to their designs. “The minute someone becomes your employee and they work for you, that work becomes yours,” Devlin stated. It is important for designers to negotiate retaining copies of the work for that brand in their personal portfolios, which will never be offered but will not likely be refused.

Obscure copyright laws and the indisputable legal power of large corporations have created a hostile environment for independent fashion designers and their creations. Nevertheless, the situation is not all bad, as social platforms become a means of communication for sharing ideas and designs with a wider, international audience. This immediacy, which was not available until recent years, has become the footing for young designers to step into the industry with less difficulty. Even Hugh Devlin could not refrain from seeing sunshine after the rain: “You designers have chosen a profession, which has many difficulties, but I do not know any other sector where people can be so excited about their work.”

Credits

Text Soeun Grace Ahn

Screenshot via YouTube