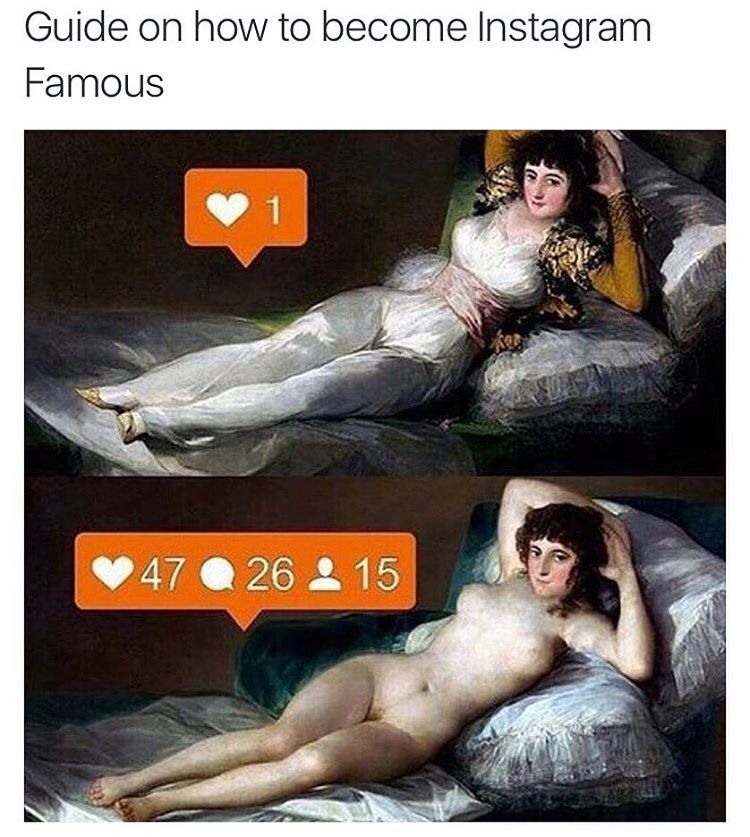

Girls getting undressed for “the gram” is a relatively new and complicated phenomenon. As with all the most important cultural conversations that happen in 2017, this one can summarized by a meme. The meme in question is one of those “classical art memes”; it’s a split screen image, with our painted heroine lying on a chaise longue. In the top image, she’s dressed in Victorian garb and the love heart icon from Instagram lingers above her head — she’s tallied up a few likes. The below image is the same girl but in this instance, she’s nude. Guess what? She’s received hundreds of likes.

We’ve all become acclimatized to the semi-naked selfie. It’s part of our everyday experience as soon as we dive into our social media apps in the morning. We glibly scroll past them on our lunch breaks, double tap our friend’s and maybe, sometimes, screenshot a few of them. It does not take a social media professional to recognize the correlation between followers and sexy pictures — the former, more often than not, multiples in accordance to the latter.

News of marketers, brands, and boardrooms wading in on the good time hit the mainstream in October 2015 when 18-year-old Australian model, Essena O’Neill, publicly announced her departure from Instagram. The teenager deleted 2,000 images and urged her 612,000 followers to do the same. A large percentage of her images were Victoria’s Secret worthy lingerie pictures, where brands were tagged in return for large sums of money. Essena revealed she could earn “$1500 a post EASY” if she tagged a brand. Essena’s growing struggles with mental health issues and body dysmorphia brought about by social media pressures ignited a larger discourse about young girls taking compromising pictures of themselves online in order to earn a living. It seemed to be a topic that most teenagers and young women could relate to even in the absence of a paycheck.

Then, in 2016, the Federal Trade commission enforced new legislation that required any social media influencer to clearly indicate when a post had been paid for with an #ad or #sponsored in a bid for more transparency on the currently poorly policed platform. As ever, corporations found loopholes and the business of young girls getting undressed online continues to be a big fat booming industry of murky moral decision making that shows no sign of slowing down. Whether it’s Kylie Jenner promoting diet pills in her underwear or a teenager in Hull mimicking the half-naked Kardashian selfie, we’re living in an age where women have never felt more pressure to look good naked — and be endorsed for doing so — online. Forget the “male gaze,” we’re living in the age of the “advertising gaze” where brand endorsement or just plain affiliation (search the 25,000 posts tagged #inmycalvins, for example) is shaping the way we see ourselves.

Whether it’s Kylie Jenner promoting diet pills in her underwear or a teenager in Hull mimicking the half-naked Kardashian selfie, we’re living in an age where women have never felt more pressure to look good naked — and be endorsed for doing so — online.

We live in an age where we photograph each other so ardently that people have taken to doctoring their own images. Apps, like FaceTune (which as of last year was the number one, most downloaded paid-for app in more than 120 countries) means you can look #flawless with the swipe of a finger. Young women now carry the power of their own photo studios in their pockets, and it seems the temptation proves too great (and who can blame them?). The question of why women, after being raised on a force-fed diet of altered images and “Hello Boys” advertising should owe anyone their “real face” or their un-edited bikini pictures is an important one. Quite frankly, they don’t. One of the Daily Mail’s favorite pastimes is to call out everyone from Kim Kardashian to D-List reality TV stars for their cack-handed photo-editing (like, wonky curtains and waves in paving tiles), while simultaneously enforcing the unattainable beauty standards these celebrities are trying to live up to.

Of course, Essena O’Neill’s story was only one side of the credit card. There’s also the legions of body positive activists who were gaining influence on Instagram with accounts that were assertively reclaiming the female body. We had started to witness major kick back from women who’d simply had enough of the “perfection” that was being peddled to them, and there was a huge appetite for it. There was a sense that these digressions had amazing potential to bring visibility to new ideas on a public platform: women of color, plus-size women, and trans women were autonomously using Instagram as a tool to spread a genuine message around the beauty and importance of diversification. They came with a “breathe out,” “no fucks given” mentality that spoke to lots of people who were also fed up with feeling inadequate.

Body positive accounts like Molly Soda, Maja Malou Lyse, Gabs Fresh, Ericka Hart, and Ashley Armitage felt long-waited for; radical, powerful, and anti-establishment. They were part of a refreshing post-Tumblr cohort of a intersectional feminists, bravely sharing candid images of what a womanly body can and often does look like; stretch marks, eczema, dark black and brown skin, surgery scars, wobbly flesh and large breasts, pubic hair and varicose veins — nothing was censored.

And now Instagram influencers have replaced traditional models and the lines are becoming increasingly blurred. “Personalities” like gap-toothed Slick Woods, freckled Salem Mitchell, and curve model Georgia Pratt, are examples of people eschewing traditional Western beauty standards. And they’re gracing the catwalks and fronting the fragrance campaigns and that is a great thing. So why do we all still feel awful? Why have sales for beauty products and designer clothes not plummeted with the rise of “real beauty” influencers?

While it may feel like progress, swapping in one beauty ideal for another means we’re still dealing in the currency of aspiration, and aspiration by definition doesn’t feel authentic or attainable.

A recent study conducted by Dove Beauty found that British women have the second lowest self-esteem of any nationality, with only 20% of those interviewed being content with the way they look. There’s even NHS Digital research that shows that 26% of women, aged between 16 and 24, have suffered from symptoms of mental health conditions like anxiety and depression — which charities claim are exacerbated by women’s vulnerability to social media. The facts are, even the most “real” body activists are on the whole beautiful, and even if the intentions are good we’re still fetishizing these women.

While it may feel like progress, swapping in one beauty ideal for another means we’re still dealing in the currency of aspiration — and aspiration by definition doesn’t feel authentic or attainable. There have been speed bumps too that must be mentioned. Take H&M’s #Ladylike campaign that starred Paloma Elsesser and trans model Hari Nef. It was a bid to show a big fashion brand getting behind “normal” women doing “normal” things in their underwear and in the boardroom — and it almost worked. The backlash that ensued largely focused on the hypocrisy of a brand like H&M supporting marginalized women — a fast-fashion brand that has been entangled in child labour disputes, and has also been accused of running limited stock for plus size women.

Or take curve model Emma Breschi. “I don’t think girls seeing female nudity is the problem,” she told i-D. “The problem is how negative people react to the nudity.” I asked Emma why she thinks Instagram can be a place of respite for weary women. “When I was a kid I didn’t have a body positive role model. I went through a lot. Now, with platforms like Instagram, we have people we can turn to, who offer a different view of what a woman looks like. I love when people use their naked body to project positive messages and challenge the world’s boring conservative views on the subject.”

As we find ourselves waist deep in the oil slicked waters of Instagram advertising and influencer marketing, we must champion accounts like Emma’s that are leveraging her own influence and brands’ reach to reverse the fault lines and restart the conversation around female flesh online. We must reward the women attempting to rid the naked female body of shame; desist from rewarding the nakedness we see in advertising and stop punishing the self-shot flesh we see online.

Through conservation, education, and inclusion we have to positively reaffirm that we are good enough as we come and we have to seek out new ways for young girls to self-fashion outside of the confines of an iPhone and an Instagram border. We must begin at home too, as women, to rid social media anxiety of taboo — to not infantilize or diminish its potent ability to reduce women’s importance down to the way they look. We must begin by admitting that most of us feel alienated by our own bodies and social media and that is not ok, and we must start again from there.

Read: A guide to rejecting white beauty standards and learning to love who you are by Ebonee Davis.

Credits

Text Nellie Eden

Image via Instagram