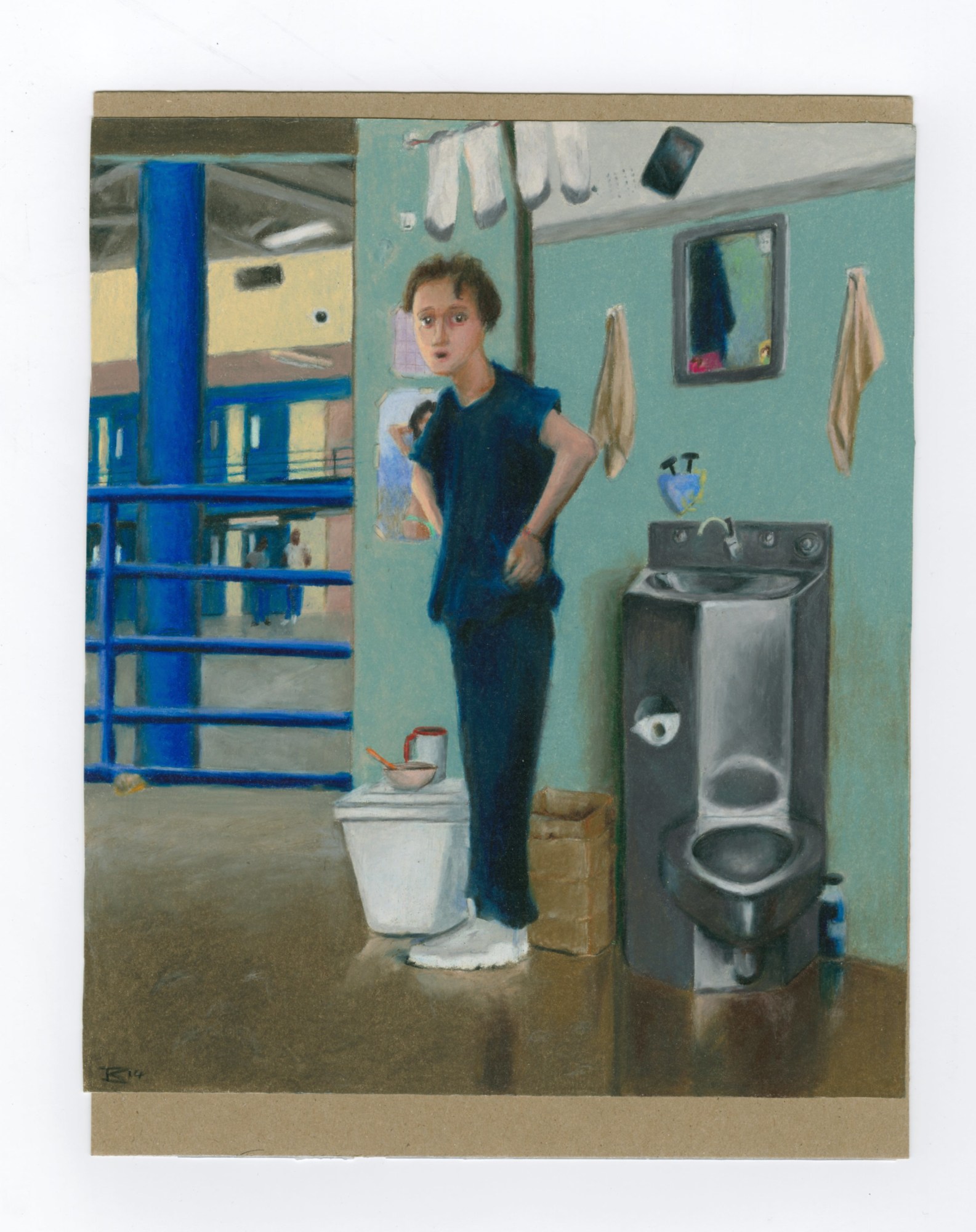

With a sachet of Kool-aid, an asthma inhaler, and a little know-how, you can create an airbrushed artwork. If you don’t have access to glue for mounting or collaging, a mixture of powdered milk and water makes a half-decent alternative. These are just two things Tatiana von Furstenberg learned about the varying practices of the thousand-something incarcerated LGBTQ artists who submitted work for the new group show On the Inside.

The exhibition, now on display at the Abrons Art Center in New York’s Lower East Side, was four years in the making. The idea formed when Von Furstenberg (daughter of Diane) came across the organization Black and Pink while researching pen pal programs online. Tatiana has a muscle disease which often leaves her tired and she’d figured sending letters might be a non-physically demanding way to make a difference. Run by a network of formerly incarcerated LGBTQ volunteers, the nonprofit mails out newsletters to a growing list of LGBTQ prisoners around the country, providing valuable updates and community.

Black and Pink’s newsletters, Tatiana noticed, were illustrated with artwork sent in by the inmates themselves. And so, in collaboration with Black and Pink, she put out a call for artist submissions, in the hopes of curating an exhibition. At first, responses were few and far between. “I would go to the P.O. Box and there’d be barely anything there,” Tatiana remembers. But soon momentum built. “Maybe people were talking about it, but suddenly it just ignited, and I was getting hundreds of artworks from a few particular institutions then another facility and another facility.” Four years later, she says, the response had become overwhelming.

“I was getting so many submissions and it was hard to process them with the level of integrity that I wanted,” says Tatiana, “and everything was done by snail mail.” She was insistent that every work she didn’t include in the show should be returned to its creator. And she made donations into artists’ commissary accounts in payment for their contributions. Because of legal restrictions, artists had to agree to “donate” work for the exhibition. And Tatiana felt strongly that the pieces should not be available for purchase.

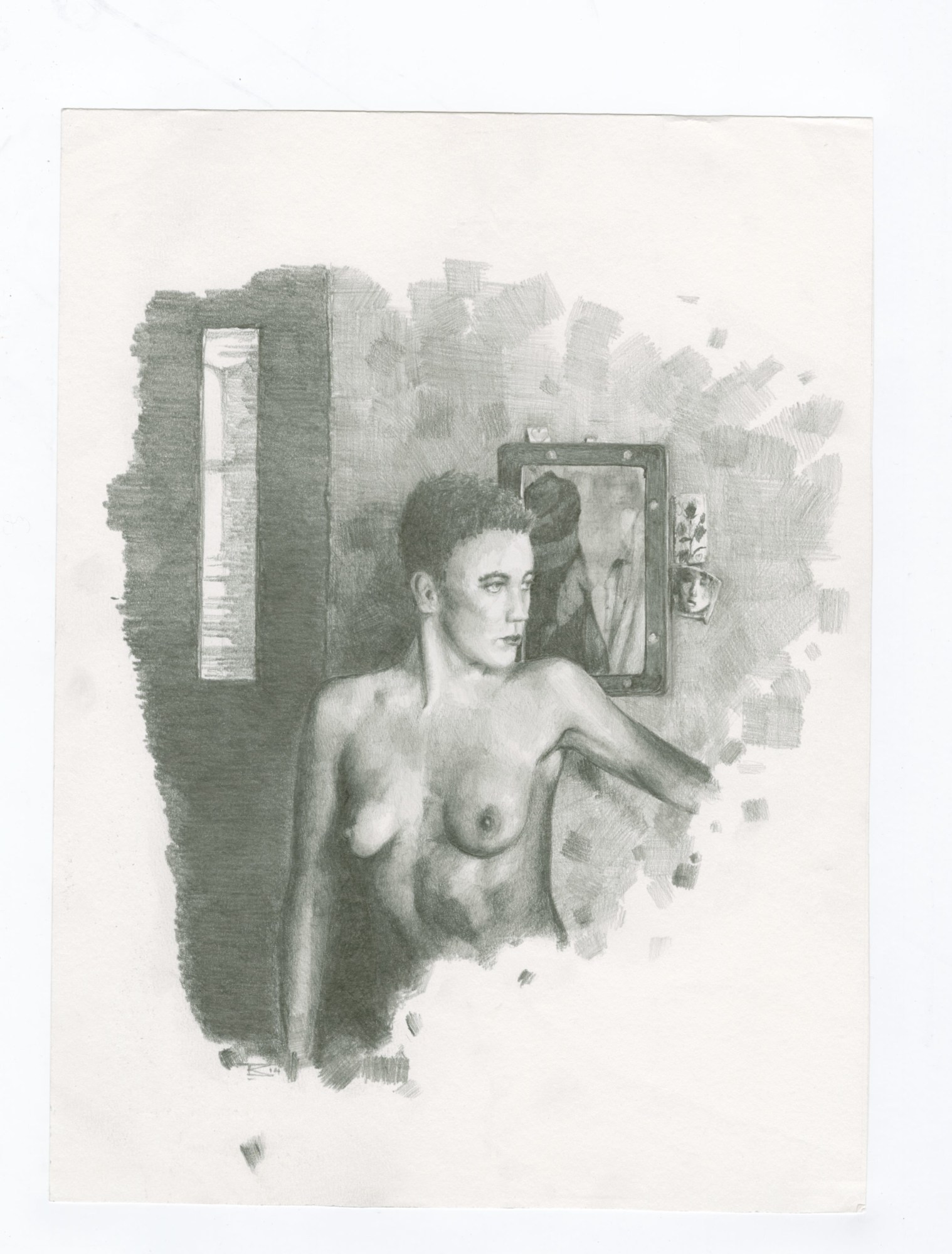

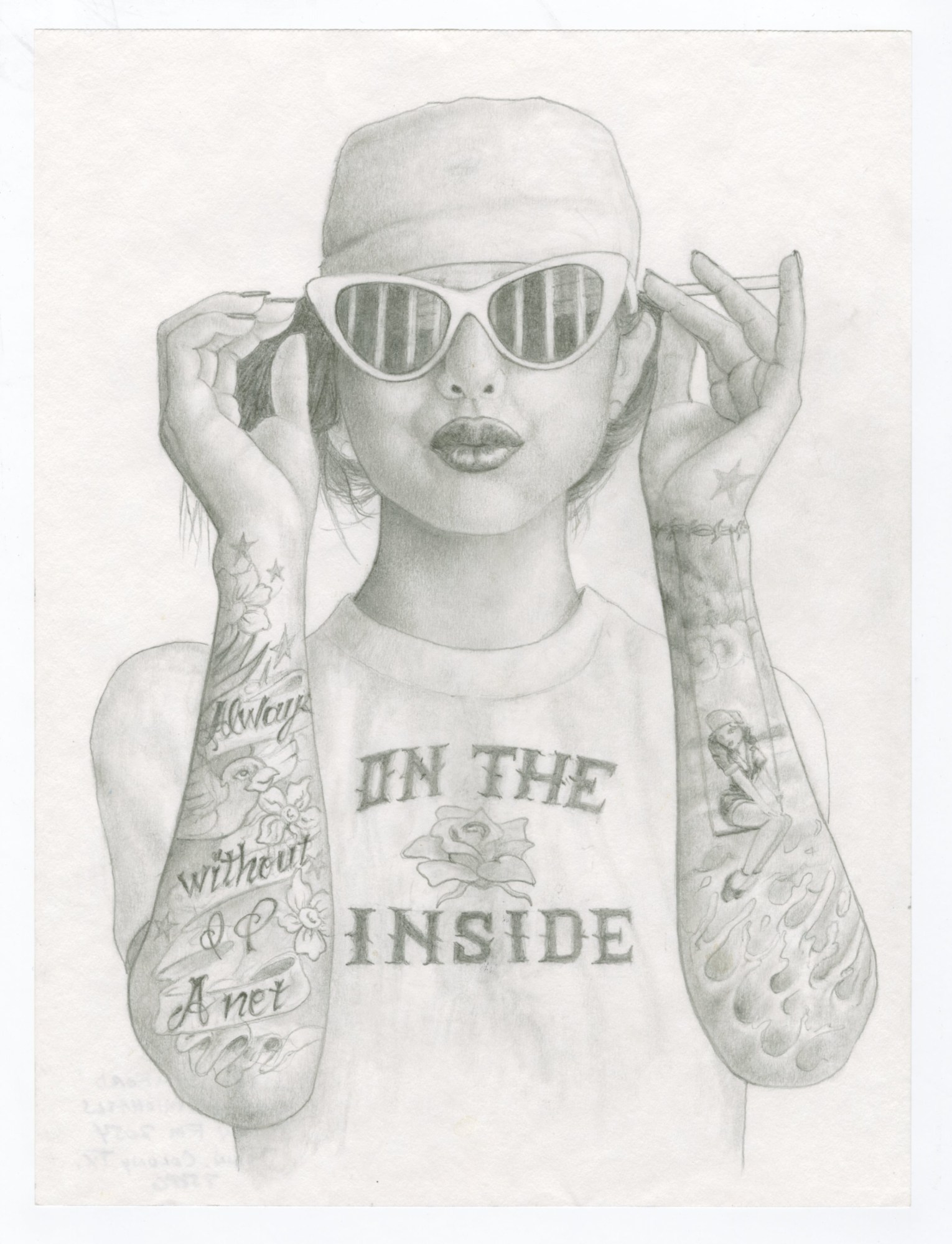

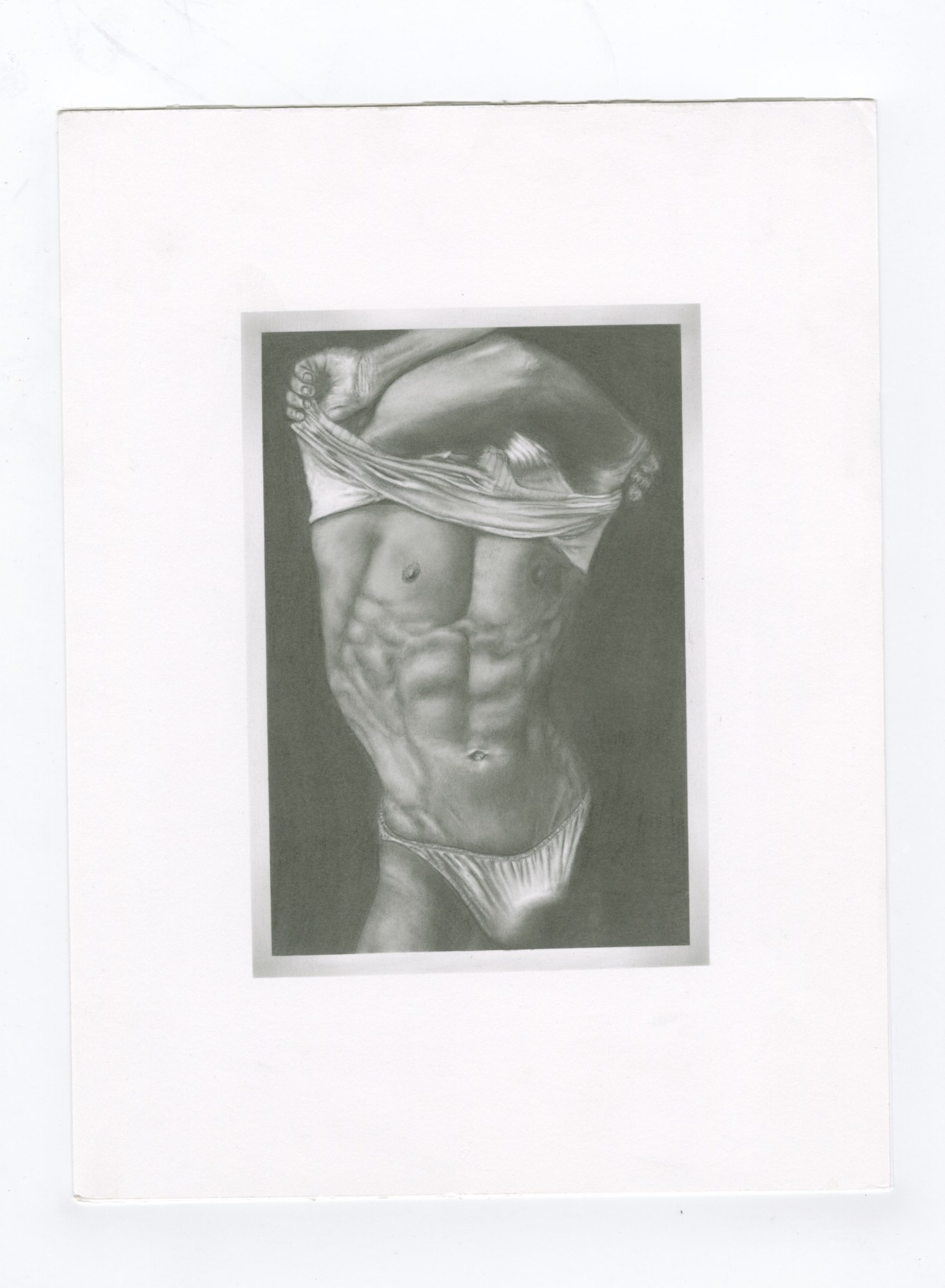

“I don’t want to commodify this work,” she says, imagining with distaste the idea of positioning “prison art” as a hot new form of outsider art. Everything from the wording of the show’s publicity materials to its installation represents a considered effort to not confine the works on display to the context in which they were created. “These are artists who happen to currently be incarcerated. Period. And I didn’t want it to be an anthropological show, which included the letters and envelopes. Even the way that I framed it, I didn’t want it to be decorative, I wanted it to be professional.”

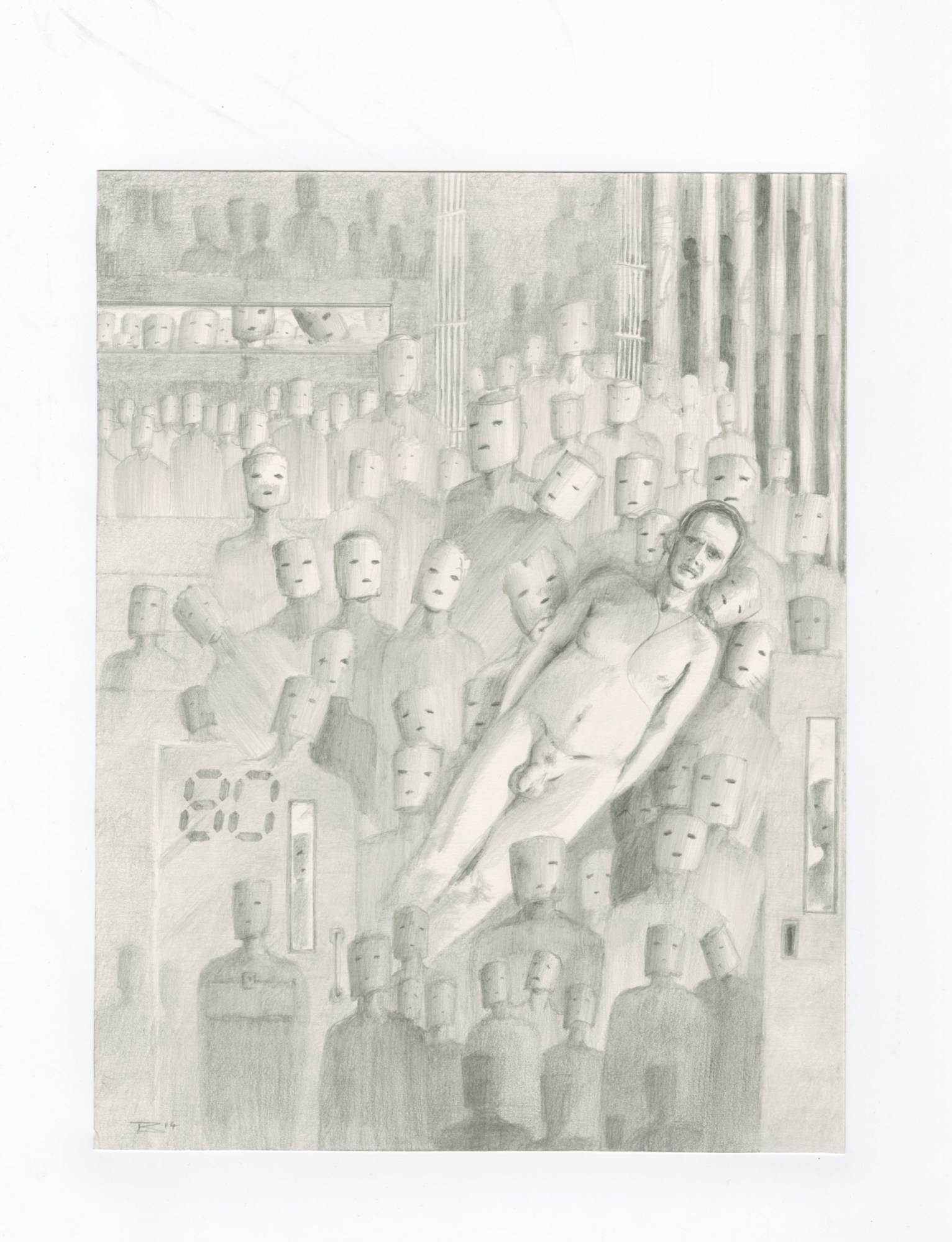

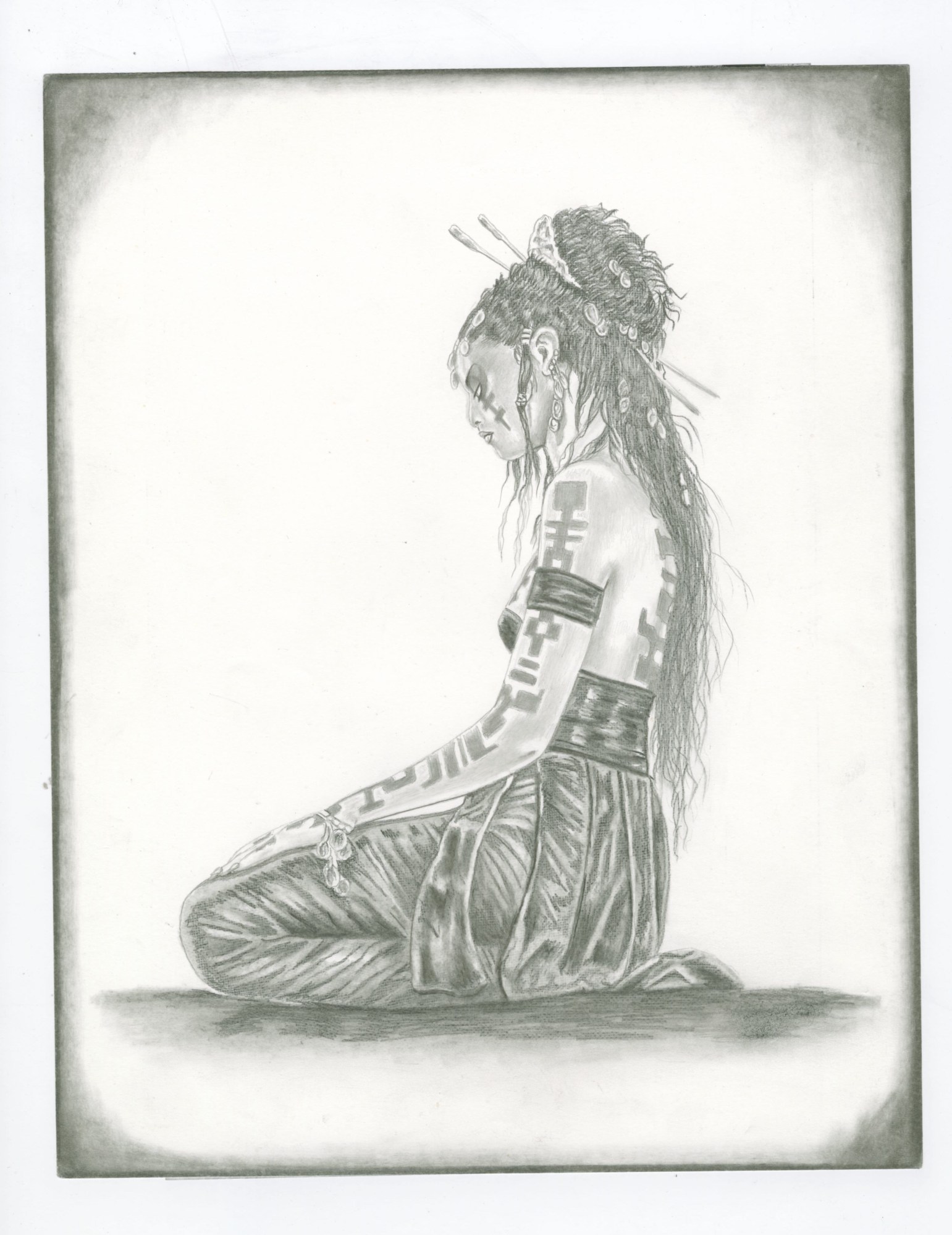

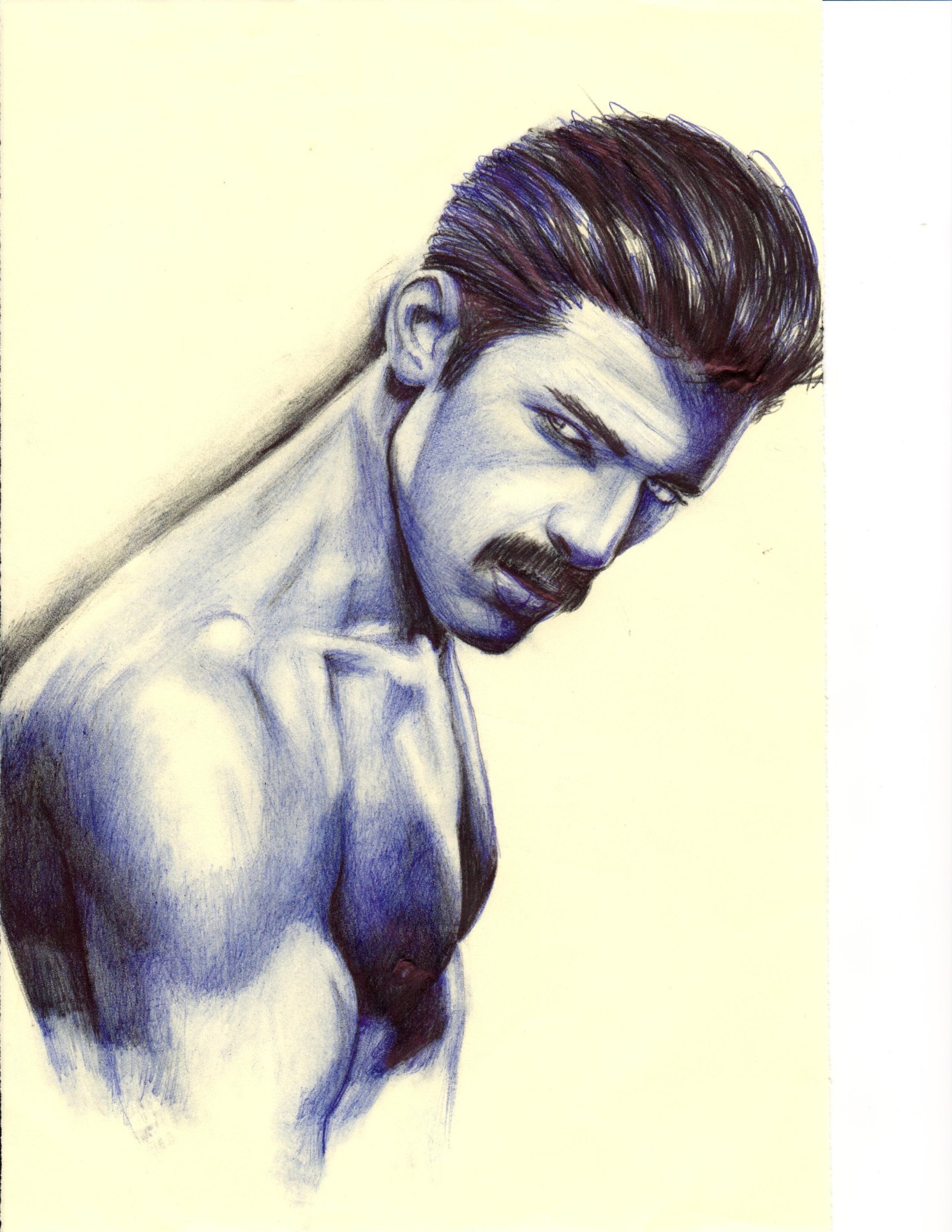

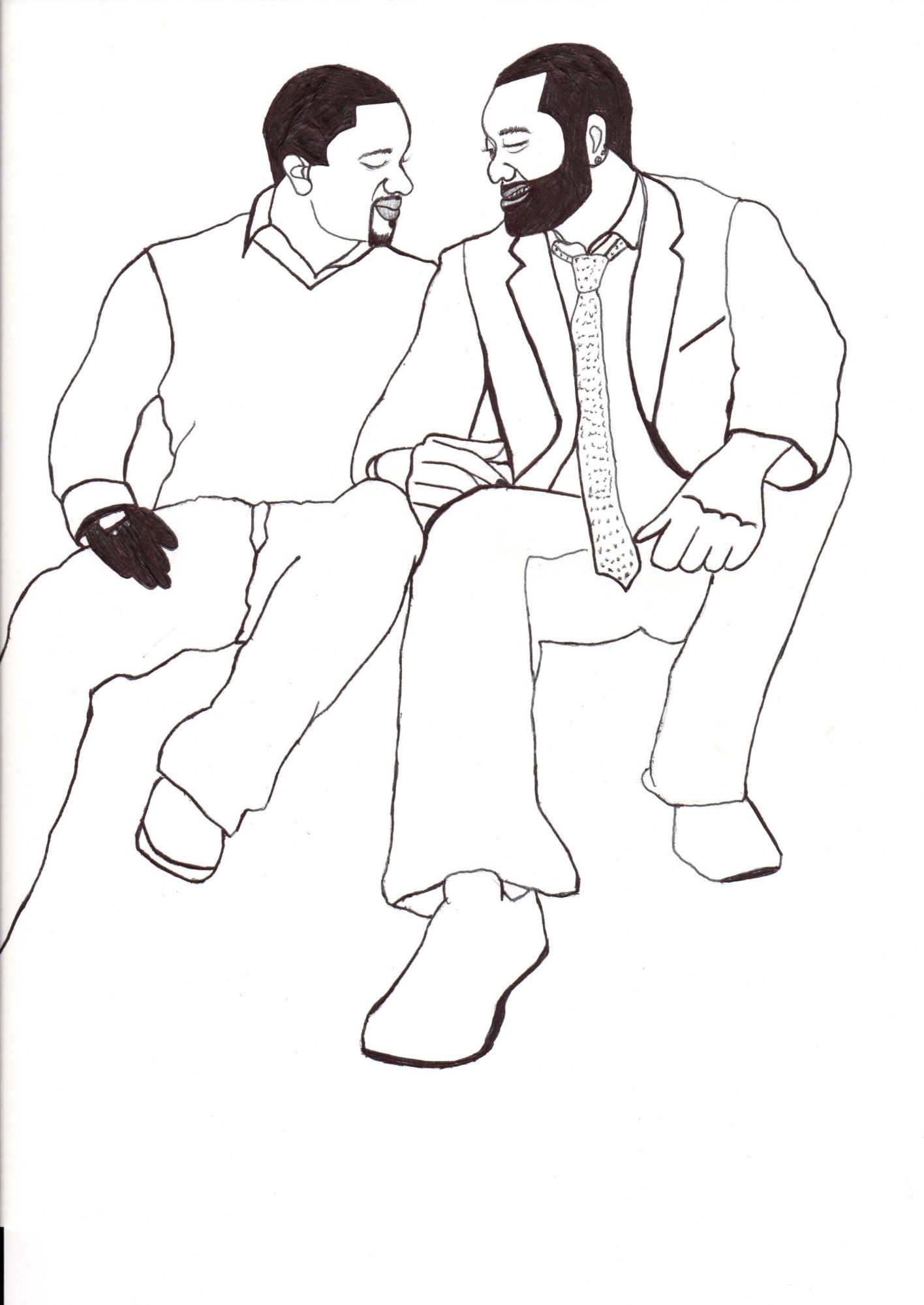

Eighteen months into the project, when Tatiana spread out a group of early submissions on her floor, certain themes immediately jumped out. “There were no conceptual interpretations of the prison experience. The works were very direct. It was all about soul expression, showing themselves as they are. I got a lot of ‘I’m so fucking hot’ self-portraits. I got a lot of true spirit representations — there were fairies, mermaids and elves — and a lot dealt with love and affection rather than sex. You’re not allowed to have physical contact in the facility, and that’s absurd. Everyone needs human touch.”

Another common theme was celebrity portraits. Specifically, drawings of Rihanna, Michael Jackson, Marilyn Monroe, and Robin Williams. I ask Tatiana why those four? “If you’re not allowed to have a relationship with somebody — anybody — then you might as well have one with Rihanna,” she explains, “At least she’s giving you music and images.” Many LGBTQ inmates have little to no communication with family on the outside, who have often severed ties. (“Sometimes the Black and Pink newsletter is the only piece of mail they get,” says Tatiana.) Rihanna at least gives back in some way, supplying music in an unknowing exchange for shaded pencil renderings of her likeness. “She’s also relatable,” explains Tatiana. She suggests all four subjects share a blend of strength and vulnerability that speaks to the incarcerated LGBTQ population.

“If you’re a trans woman and you go to a male prison and you have with double-Ds, that’s super, super scary,” Tatiana says, “They’re asking to be put in solitary confinement, otherwise they’re in danger. You have to go through a lot.” Many of the artists involved wrote, in letters accompanying their submissions, that they didn’t think anyone even cared about their experience.

“The correspondence was really overwhelming. This show offered hope,” says Tatiana. She included quotes from the artists’ letters alongside their pieces, so their voices would be heard. Visitors to the exhibition can also “text” artists responses to their work, thanks to a transcription service that will print and mail viewers’ feedback to the artists. “We have to encourage these artists,” says Tatiana. “My intention always was to not use these artists as entertainment. We have to give something back, we can’t just enjoy it.”

“On the Inside” is on show now at the Abrons Art Center in New York.

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson

Images courtesy the artists