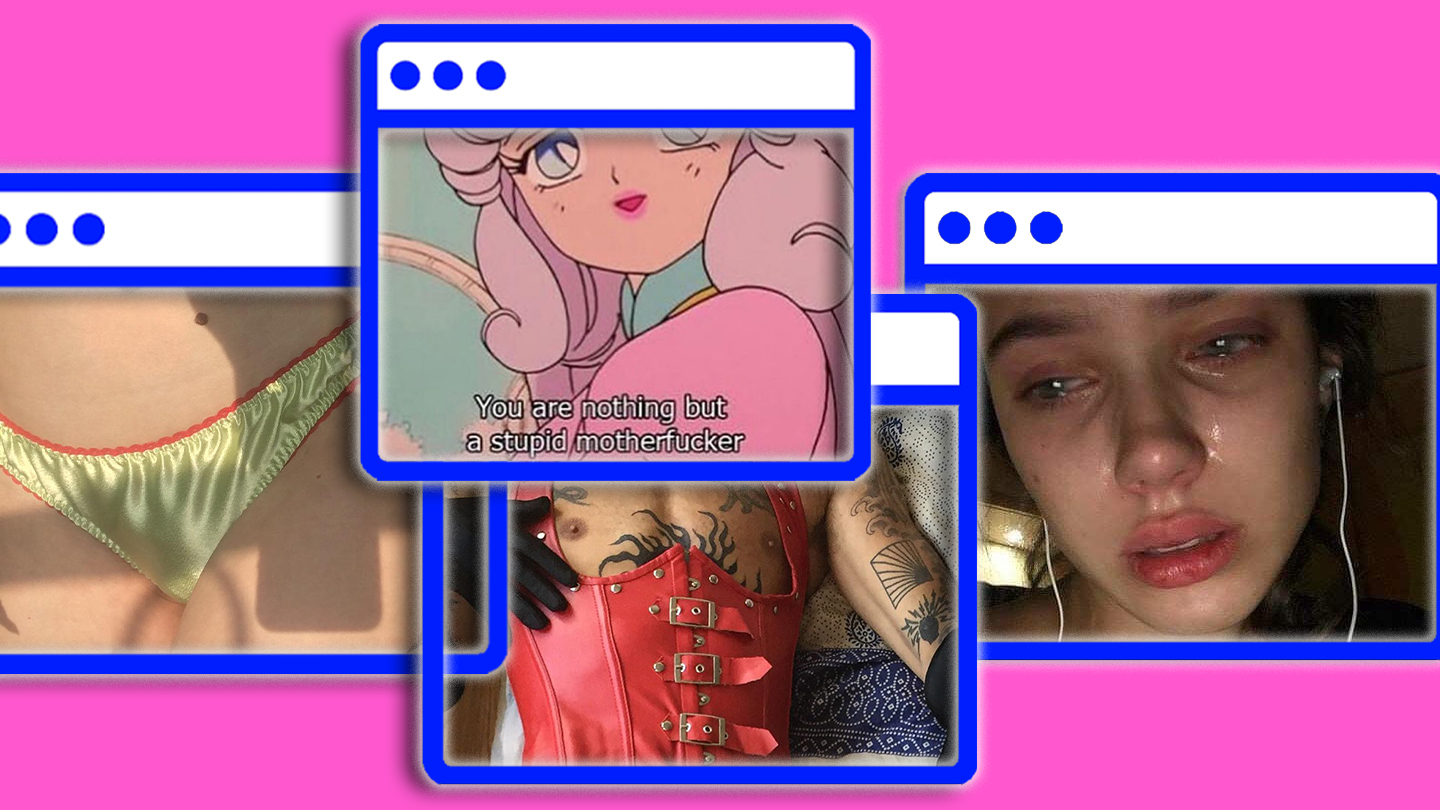

Many of us share a complicated relationship with social media, negotiating digital spaces and the amount of ourselves we share online. Social platforms are how we find and form communities, how we build followings and even become brands. The positives (and negatives) of social media are ever expanding, and over the years the likes of Instagram have become a work portfolio, a forum for discussion, a tool for vetting potential dates, an archive, a method of sending blanket updates to those closest to you and more. It’s no wonder that as the uses for Instagram multiply and our follower counts swell, more and more people are attempting to carve out spaces for themselves in their corners of the internet through Instagram’s close friends feature and finstas.

For many, finstas, a normally private “fake” Instagram account often used alongside a person’s main account, are where only your follower list is carefully curated; when it comes to content, there is no filter. At first glance, finstas and the close friends feature appear to be for connecting with people you already know, but as these spaces have popularised, it’s clear that things extend beyond that. Being a close friend IRL doesn’t necessarily grant you access to these spaces. In fact, in some cases, users are less inclined to add certain close friends out of fear that they’ll worry about the content being shared.

These spaces go beyond being just private; they are carefully considered forums that are constantly shifting, with users adding and removing friends depending on what they decide to reveal. Considering that, for many people, reasons for starting a finsta account include feeling able to be more candid about mental health and relationships, where does that leave our existing main accounts? Can they be cultivated? Or should we simply get rid of them?

“Finsta is just mess,” says Leo, a writer from London. “I use my finsta as a giant group chat and all the accounts that follow me on there are other finsta accounts.” Despite wanting to use her socials as a way of exploring ideas and making sense of the world, Leo found that she was becoming wary of the opinions she was putting out. “If I use my main platform with 1,000 followers, I don’t want to put out something that’s ignorant or a bad opinion. My finsta is a space where I can be a bit more ignorant, ask more questions and know that there aren’t going to be the same repercussions.”

“It’s weird having loads of people seeing your stories but then only one or two people send you a message; it feels a bit like people are skipping past your life.”

Leila*, a model and writer, created her finsta account after she suddenly accumulated a following of over 100,000 on Instagram. “It felt unfair putting people in my personal life on my main Instagram because it was a breach of their privacy,” she tells i-D. “Also a big following meant that I unconsciously became a ‘brand’, so pictures of me hanging out with my brother may not have necessarily fit that.”

Now that Leila’s Instagram has become a place of work for her, locking it down or taking herself offline isn’t an option, particularly because she doesn’t feel like she should have to. It’s why she created a finsta, which has about 50 followers: “I believe that I’m entitled to take up space on the internet,” she adds.

The possibility of gaining work through social media is also a factor for Leo: “I find that if I’m not in a good place with my mental health, I can end up telling strangers that I don’t care. I felt like talking about not being okay on my main Instagram was messing up my money and making me seem unreliable.”

For H*, a non-binary brown person, they want to be visible about their queerness online but struggled with how much of that they want to share. “I have old school friends who follow me on Instagram and I almost want them to see how I’ve changed,” they explain. “Like, ‘Hey, I wasn’t just a weirdo, I’m actually trans and queer!’ It’s nice to be able to show that off a little. But I don’t necessarily want them to see the most intimate moments of my life.”

H started using a close friends list on Instagram after feeling particularly exposed when they shared a comparison picture of themselves nine months after they started taking testosterone on their main Instagram grid. “Close friends gives me a voice without opening me up to too many people. It’s where I was able to talk about feeling anxious about going to a gender identity clinic.”

H finds that having a curated list of followers is not about entirely escaping the gaze of others, but actually feeling even more seen by a select few. “It’s weird having loads of people seeing your stories but then only one or two people send you a message; it feels a bit like people are skipping past your life,” they note. “When I use my close friends list, more people engage with me. I think there’s an element of ‘This person considers me close enough to witness this stuff so I feel comfortable enough to comment’.”

While many positives can be ascribed to finsta and close friends lists, should we still maintain caution even within these spaces? Krish, a genderqueer person of colour, suggests that because of the way many online friendships are formed, there is still an element of risk around who you let into these curated spheres. “Often you’ll put people in that list that you don’t actually know that well and you’re telling them really intimate parts of your life,” they say. “Some of the people on my close friends are actual friends that I see regularly and would invite to a bar for my birthday, but some are just people I trust to have the same opinions as me.”

While Leo admits that she has some people on her finsta who she’s not particularly close to in real life, the fact that they’re following one another’s finsta accounts can create an unspoken trust pact. “I know you’re not going to share anything [that I say on my finsta] because I’m also seeing your inner dark thoughts. It’s not based on the closeness of friendship, it’s about whether they’re equally as messy as me.”

“I almost quite like that it isn’t a ‘safe space’. I very much use it as a space for leaning into the fuckery.”

However, when a friend of a friend sent Leo a screenshot of someone’s finsta page, it felt like a violation of the fundamental rules of finsta. “The screenshotted post didn’t actually say anything bad; it was more them saying, ‘Look at this’. But I felt really uncomfortable with them sending it to me because if you’ve done that to that friend, you could easily do it to me. It wasn’t explicit information or particularly private, but it felt like they had broken the law of how finstas work so I removed them from my followers.”

Although this is a risk, as it is with sharing any personal content online, the virtue of these more private spaces is that your choice of who accesses them is curatorial. There is a form of control offered to finsta users that ‘s sometimes missing from public main accounts. “I remove and add people at my wish,” says Krish. “Sometimes, if I’m going through a specific incident or when I’m thinking about gender quite heavily, I might remove people that I don’t want on the list. But then if I’m talking about race and religion, I might add some people on. It’s an ever-evolving space.”

For Leo, it’s important to make the distinction that having a controlled space doesn’t make it a “safe” one — it simply means that she feels more able to get things wrong without massive consequences. “I almost quite like that it isn’t a ‘safe space’. I very much use it as a space for leaning into the fuckery. I’m happy for people to call me out because you need spaces to learn and grow. The only way you get better is to have actual space to explore and discuss ideas, but I guess that is a form of safety in its own way.”

Creating dedicated spaces that don’t require as much filtering or performance begs the question of permanency; will we always need these features in order to feel like we can communicate our vulnerability online? Krish hopes that one day they’ll be able to cultivate a group of real life friends who can reflect what they gain from their close friends list. But for now, it’s a necessity. “As a carer to both my parents and living in a homophobic household where I’m not out to my parents, I need this right now,” they say.

Meanwhile, Leila believes that the respite her finsta offers her is unmatched: “It’s a place for me to share personal achievements, my feelings, things happening in my personal life and more without worrying about being narcissistic. It gives me control over my digital self in a space where so much of me is exposed.”

Using close friends, and in particular, finsta goes beyond simply feeling able to bitch and share unsightly selfies. They provide an outlet for exploring different parts of our personalities and for using a different voice within the digital space, with people who don’t have to meet the criteria of being close friends in real life. There are unwritten rules and bonds of trust rooted in mutually assured messiness with constant curation and monitoring of who is allowed access to the space. The spaces reflect the realities of life — that we are all constantly evolving, shedding and negotiating how we take up space.

Reasons for creating these selective pockets of the internet are endless, but they offer all users the same things: a digital bubble where they can dictate how much they give of themselves and who they give it to. Despite craving these private spaces, however, we’re still not willing to give up our main accounts, whether due to the ease of keeping up with people we care about, because you have to be careful with your brand for work opportunities, or simply just wanting to feel seen and visible.

We’ve built followings, audiences and communities, which means that for many, taking yourself offline entirely isn’t viable in the long term. However, we also acknowledge that these platforms encourage us to present our best curated selves. As long as this ongoing strain to perform and carefully present our lives online exists, there will always be something appealing about cordoning off part of the internet for yourself.

*Some names have been changed