This story originally appeared in i-D’s The In Real Life issue, no. 364, Autumn 2021. Order your copy here.

Exactly four years since Azzedine Alaïa’s last ever fashion show in the wrought-iron courtyard of his Rue de Moussy headquarters and the streets outside the same building are lined with the bright glare of Klieg lights and rows of black folding chairs. It’s a wet, balmy, early July evening, and the clouds have briefly parted for Pieter Mulier’s debut for the house on the eve of the couture shows in Paris (it is not officially a part of the schedule, just as Azzedine would have wished).

At one end of the single-block street is a gay bar clattering with summertime drinkers, at the other is a Monoprix supermarket, and in the middle is a sex shop displaying jockstraps in the window. The high-low ambience is only heightened by the thrumming crowds of Parisians tiptoeing to get a look-in, alongside Raf Simons and Pierpaolo Piccioli smoking outside, the dazzling arrival of Farida Khelfa and Monica Belucci, and 200 of fashion’s usual suspects once again finding their bearings on the world’s most fraught map: the seating plan of a real-life fashion show.

Excitement is in the air. Fear, too. A lot is resting on this moment. In the three years since Azzedine Alaïa’s passing, the brand has reissued pieces from the archive that feel timely, a sort of greatest hits compilation, but now is the moment for evolution. It was always going to be a tough job. And the question wasn’t so much who would do it, but how.

How can you even begin to measure up to fashion’s last true couturier? How do you renew something timeless?

How do you improve perfection?

But fashion is about the now and the next. And for the older guard of fashion veterans, who knew Azzedine and sat at his dinner table, it was always going to be difficult to watch someone else sit in their beloved’s chair. For a younger generation, Alaïa isn’t much beyond a namecheck in Clueless. The challenge isn’t so much to reinvent the wheel, but to keep it moving. Cher Horowitz was a high schooler in 1995, and even she knew Alaïa was, “like, a totally important designer”. Today’s kids need to know that, too.

At the show, on each seat lies a letter from Pieter. “Dear Azzedine,” it reads. “This collection is intended as a tribute to thank you, to express my sincere respect and recognition for the work you did… I tried to get into your mind, but that’s impossible… We met but I never had the opportunity to know you. Now, I have the opportunity to thank you.”

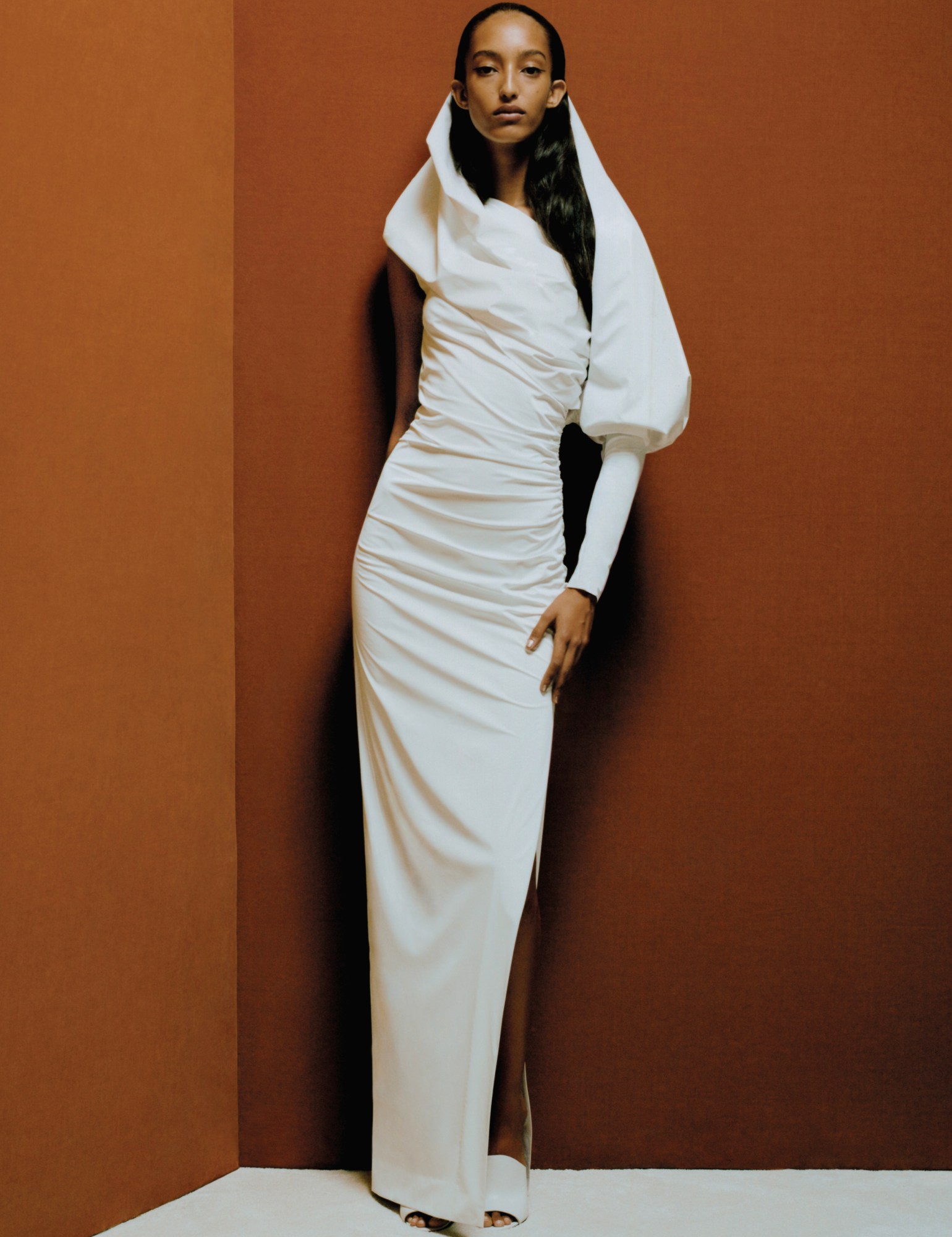

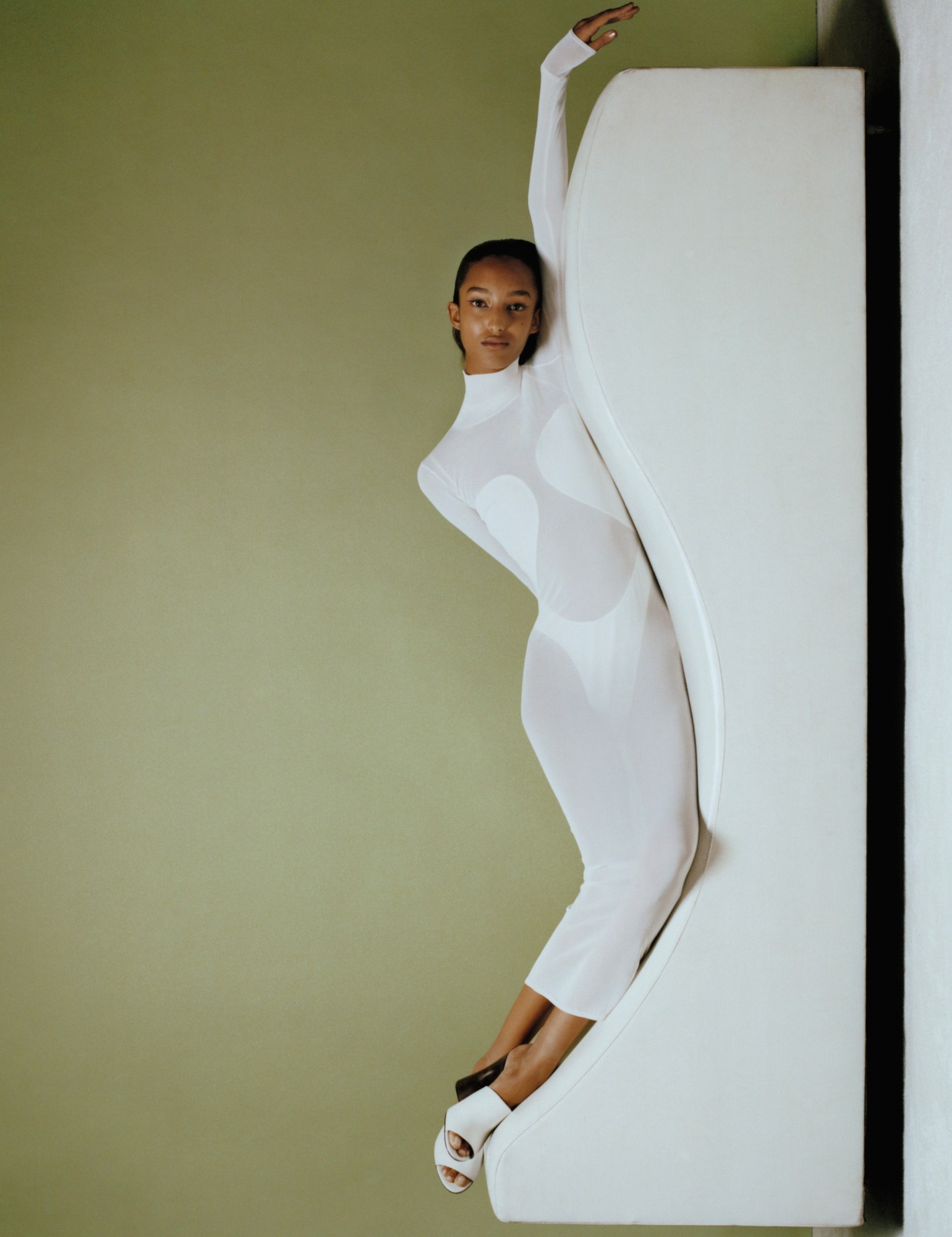

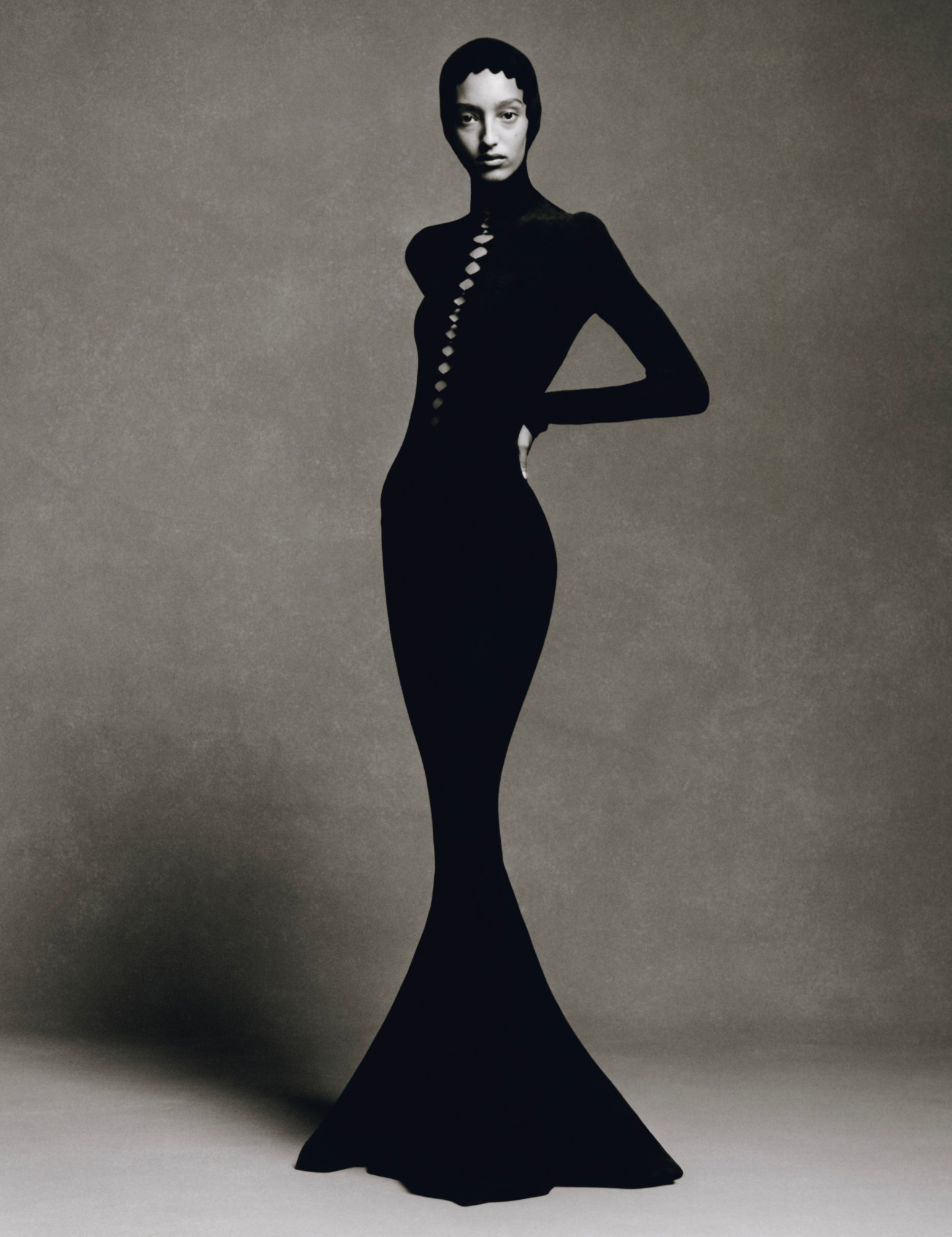

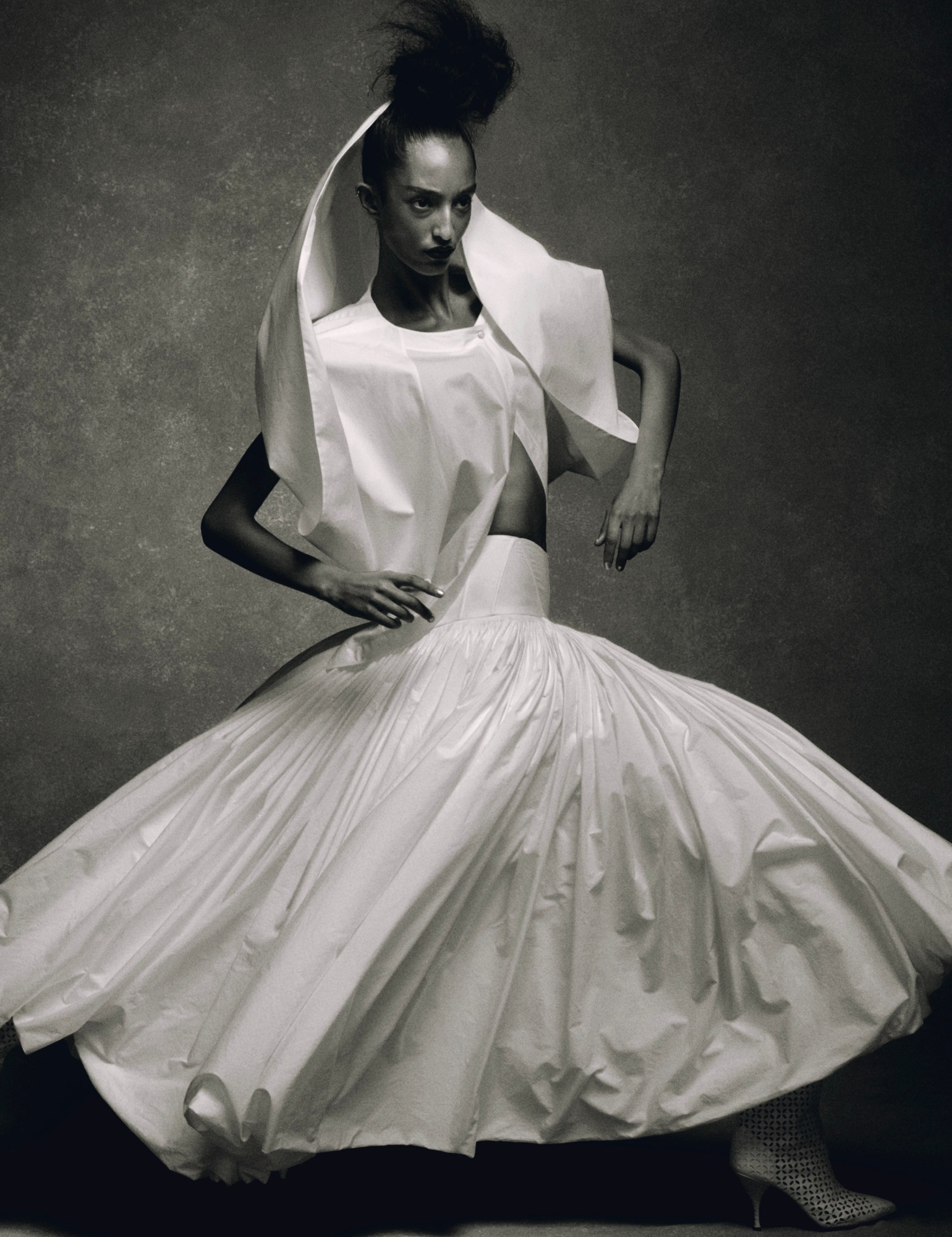

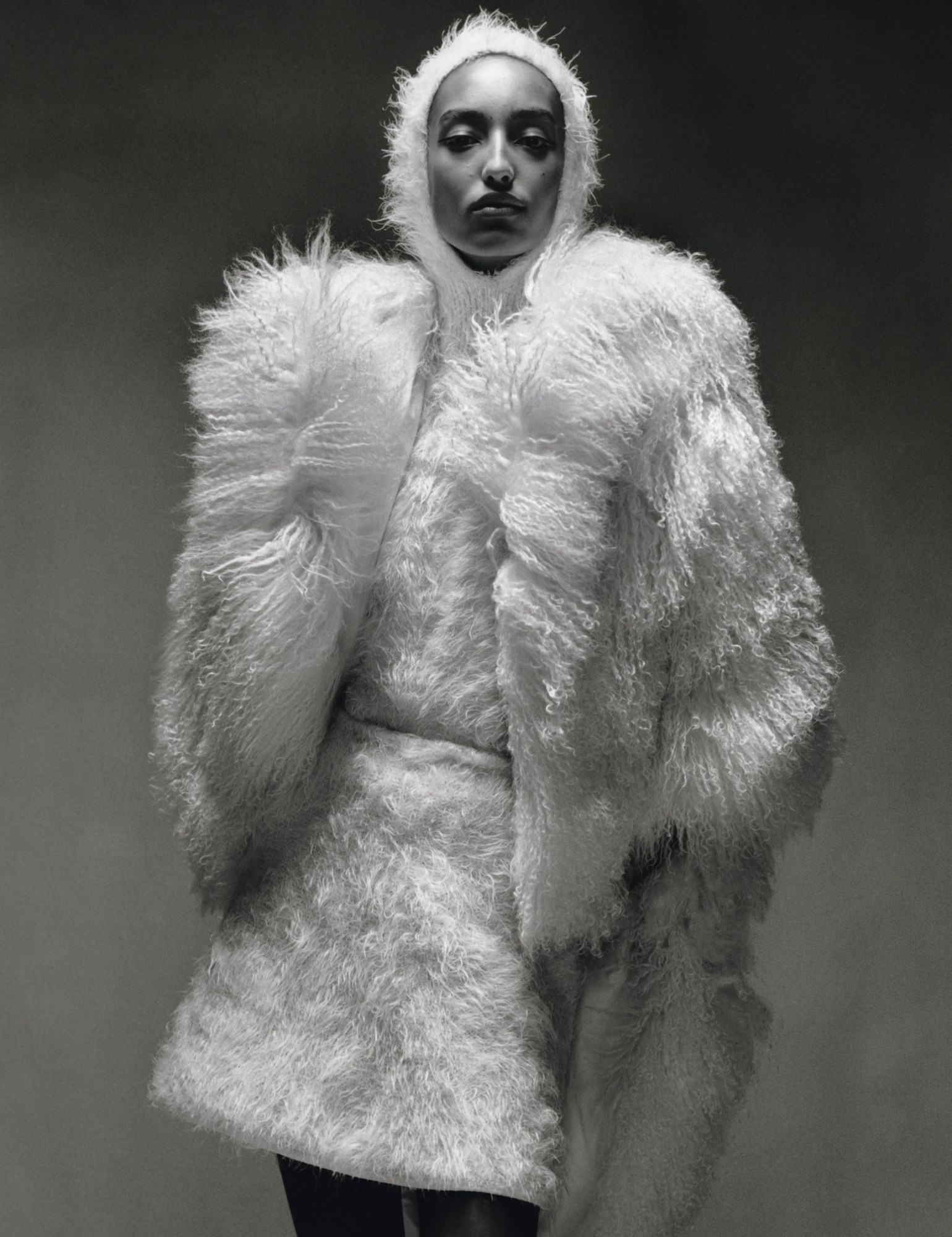

As a North African beat begins to blast, the girls arrive with a swing in their stride, first in hooded black tailoring worn over buckled stomacher belts, and then in slinky catsuits, sculpted leathers, figure-hugging knits and draped plissé dresses and dove- white cotton skirts. That’s putting it simply (more on the clothes later), but the point is it’s the Alaïa classics not seen since the 80s and 90s, their silhouettes and colours at once familiar and freshened up for 2021. It’s respectful, but also a reminder of what Alaïa was; a creator of sexy, assured, shape-driven clothes that make women of all ages and body types look like otherworldly sculptures, but also, and importantly, feel comfortable.

By the end of the show, there’s a collective sigh of relief. Raf Simons is in tears. His right-hand man of more than 20 years has stepped into the spotlight, is being flooded by journalists and has the whole world watching.

Pieter Mulier, the Belgian designer who played the supporting act to a designer making his big couture debut in Frédéric Tcheng’s 2014 documentary Dior and I, just became a superstar in his own right. All eyes are on him.

Two months before the show and Pieter is dialling into Zoom from the glass studio on the top floor of Rue de Moussy, a cigarette in hand, to talk about his new job, which he calls “the holy grail for anyone who works in fashion.”

“I said yes immediately,” he says. It had been a year since what he calls “the New York escapade”, referring to his last role at Calvin Klein, where he was global Creative Director to Raf’s Chief Creative Officer.

There, Pieter was working with a design team of more than 400 people. Stakes were high, given the top-to-toe rebrand.

It ended abruptly with the Raf crew’s departure in 2018, after which Pieter took time off to pause and return to live in Antwerp full time (he was commuting from Belgium to NYC every week). “I decided it was enough. I had it with the fashion world as it was,” he frowns, exhaling a flute of smoke. “I had burnout. I needed some time, and I had a year off.”

Then came Alaïa and the promise of a volte-face for the designer. During his year of relaxation, the self-described “fashion addict” came close to not returning to it at all. For more than two decades, he had been at the side of Raf, “always very comfortable in the shadows.” Other houses called about creative directorships, but Pieter says, “The idea of being in the spotlight always scared the shit out of me. But when Alaïa called I wasn’t scared, because inherently this house is not about me. I am not the most important thing. I’m just the caretaker.”

Caretaking feels apt for a small family- business, and one that has remained carefully independent, largely because Azzedine refused to be a part of the fashion system. He showed his collections when he was ready, believing that the relentless pace of fashion was not just detrimental to the creative process, but more importantly, turned women off.

Instead, he took his time and put care into perfecting pieces over years to create the most timeless garments he could. He worked like a sculptor, hands-on, rather than just merchandising product, and the brand’s independence, as well as its archive and foundation, is fiercely guarded by Azzedine’s loyal disciples, including his lifelong partner Christophe von Weyhe, retailer Carla Sozzani, and curator Olivier Saillard.

“It’s extremely radical, and that’s what makes this house so attractive today. As we come out of this whole Covid chaos, things need to change and this is a human way of working. It’s small and rare,” Pieter says. “That’s why I love being here, because it puts luxury back in a place where I always thought it was.” He pauses. “But it wasn’t. Luxury has changed in the last 10 years. It has changed massively. You know, luxury became for everyone.

It became about making money from a younger clientele with logos and sportswear, which killed it. It made a mockery of it and the people buying it.”

For Pieter, the idea of working with a small but devoted team of highly skilled technicians and dressmakers – there are ateliers for tailoring, leather, dresses; 24 people in total, including two generations of the same family – was a reminder of the purest form of fashion. “It’s the definition of what I always thought luxury was; it’s about clothes and humans. It’s not about fashion, it’s about construction, about making women more beautiful. It’s as simple as that.”

He hastens to add that there’s no pressure from parent company Richemont to stage shows every season, launch global marketing campaigns or, by the sounds of it, do anything he doesn’t want to do. His only condition to accepting the offer? “I didn’t want to do sportswear or sneakers.” Consider them his bête noire. Of course, Pieter is wearing sneakers – although he says he’s much more drawn to a classic shoe these days – but in his roles alongside Raf, first at Raf Simons, then Jil Sander, then Christian Dior and finally Calvin Klein, Pieter had witnessed firsthand the seismic changes of luxury houses and their approach to creation.

The bigger the business, the bigger the creative compromise, and that usually meant making very expensive, very ugly sneakers. The sneaker, more than anything, can be seen as a symbol for fashion’s shifting values. Thankfully, his new employers told him that he would never have to design a nylon puffer or a pair of sneakers, and that’s the opposite of what they want.

“There’s a modernity to small collections; it’s not just a vomiting of product,” he continues. “Richemont don’t want to make it into a billion-dollar brand, because it shouldn’t be that.” “It was like winning the lottery,” he adds. “I was euphoric when I signed the contract. Then the next day, I became really, really scared.”

There was cause for caution. Azzedine famously referred to himself as a bâtisseur – a builder of simple-looking clothes that were actually incredibly complex in construction. By the time he died, he was one of the few household-name designers who would cut his patterns himself and would do so with instinctual skill, sculpting leather like it was silk and transforming jersey and chiffon into structured armour. And though he was diminutive in stature, clocking in at just over five foot tall and never not dressed in his signature black Chinese silk or cotton pyjamas, he was a fashion giant, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the likes of Cristóbal Balenciaga, Yves Saint Laurent and Madeleine Vionnet.

Azzedine changed the look of fashion in the 80s, the period during which he earned the nickname the “King of Cling” for introducing present-day wardrobe staples such as bodysuits, leggings, metal studs, bandage dresses and cut-out leather to the catwalk. More than just the clothes, however, he also redefined the very idea of how a designer can work within the modern fashion industry, choosing to operate at his own pace and show outside the system, while remaining a globally successful business sold around the world.

It could take him years – decades, even – to develop a piece, and he was relentless in his quest for perfecting it, revisiting items years later as a sort of meditative practice of creative enlightenment and spiritual timelessness. It’s why his clothes from decades ago can still be worn.

Back then, Alaïa stood in stark opposition to the assimilation-androgyny of women in masculine suits. His clothes were bombastic and body-conscious. They were clothes for women honing their bodies with the help of Jane Fonda’s workout tapes while experimenting with bigger hair and bigger shoulders. Old-school feminists criticised his brazen sexuality and revival of padding and under-wired bustiers, which paved the way for Wonderbra explosion of the 90s. Little did they know that the world would catch up to the idea of a woman in control of her own sexuality.

When Pieter got the job, the first thing he did was go online and order some vintage Alaïa from resellers like TheRealReal. “Every time I opened the box, the only thing I thought was, ‘Oh my god, this is from 1983, and you can still wear this and look totally modern’.” The task at hand was not to make Alaïa modern, but to make it relevant again. “That’s the difficulty of this house,” he explains. “I don’t like the word ‘change’. It’s more, how do you make an evolution?”

Answer: by honing in on a specific period of Alaïa’s history, somewhere between 1983 and 1996, the years that Pieter considers Azzedine’s most revolutionary period for his designs’ “ease, sensuality and sexuality”. For him, it’s the kind of sui generis revolution seen only every few decades, like Gabrielle Chanel’s pared-back androgyny in the 30s, or Christian Dior’s ‘New Look’ in the 40s and 50s. And just as Raf (and Pieter) were seen redefining the latter for Raf’s couture debut in 2012, Pieter is on a mission for Alaïa to get its recognition in the annals of fashion history.

Something that unites Pieter and Azzedine is that they both paid their dues, quietly learning and improving on their knowledge of making clothes away from the spotlight. It took decades for Azzedine to open his own house. Born in Tunis sometime around 1940 (the exact year is hazy), the son of a wheat farmer, he grew up surrounded by a large family of North African women. As a teenager, he enrolled at the local École des Beaux Arts, where he studied sculpture. Realising he was better with fabric – though bringing a sculptor’s tactility to dressmaking – he got a job at a local dressmaker sewing pant hems, and then for seamstress Madame Richard, for whom he began making copies of French couture for the Tunisian bourgeoisie.

Eventually he landed a job in Paris at Dior, the biggest couture house at the time, under the direction of Yves Saint Laurent. Azzedine was asked to leave after just five days, due to prejudice towards his Arab background amid the outbreak of the Algerian war. He worked as a housekeeper to French aristocrats instead, cooking and looking after kids by day and making clothes for their circle of friends by night. Eventually he began freelancing for Guy Laroche and Thierry Mugler, who encouraged him to start his own business.

Azzedine slowly developed his aesthetic away from the public eye, getting to intimately know a handful of clients of all ages, shapes and sizes, as well as their diverse needs, before officially inaugurating Alaïa ready-to-wear as a fully-fledged business in 1981, with the help of his partner Christophe von Weyhe.

“I think Azzedine would have enjoyed this collection very much,” Christopher said after Pieter’s debut. “I did too, as I know that with Pieter designing Alaïa the house’s future is bright.” He added that Pieter had invited him to visit the studio and preview the collection, but he said no. “I told Pieter I wanted to see the full statement. And I’m glad I waited.”

In recent years, the Alaïa Foundation, which operates separately from the fashion business, has staged exhibitions showcasing Azzedine’s work alongside some of the finest examples of art, sculpture and mid-century couture.

As Pieter explains, “the foundation, they have Azzedine in their hearts and in their brains, but I have it in my hands, you know?” Reading between the lines, he’s saying that there’s a danger of a brand collapsing into the archive, with no real modern relevance. Clothes are meant to be worn and lived in and enjoyed, not displayed on mannequins. “You have to bring new clientele in because otherwise the age of your client goes up together with the age of the brand,” Pieter adds.

“It will just go into a museum without the younger generation tapping into it, and that’s why I wanted to bring the show to the street.”

“In the last 15 years at Alaïa, they forgot a little bit what I personally think the brand started with, which was the ease, sensuality and sexuality that, honestly, they didn’t talk about anymore,” he explains. When he arrived at the house, many of the people in it were still in mourning. As much as Pieter’s job is to bring people into Alaïa’s stores, it’s also to galvanise the people within the house. He puts it delicately: “They’d been asleep.”

And what’s one thing that wakes people up? Sex!

Alaïa, a sartorial byword for a certain kind of sexuality, couldn’t be more synonymous with the mood of 2021, which is – after a year of pent-up isolation and Zoom calls – horny, to put it bluntly. In pop culture, sex became all that anyone could talk about, and yet in fashion, somewhere between Tom Ford’s monogrammed pubes and the #MeToo movement, sex had fallen out of fashion.

Yet, for Azzedine, the female body was always the starting point. His designs confidently mapping the geography of a woman’s body in ribbons of silken bandages inspired by Egyptian mummies, in stretchy swimsuit fabrics worn with jagged cut-outs at the side, zippers and meticulously placed seams winding around the body. His creations enhanced a woman’s body rather than just containing it.

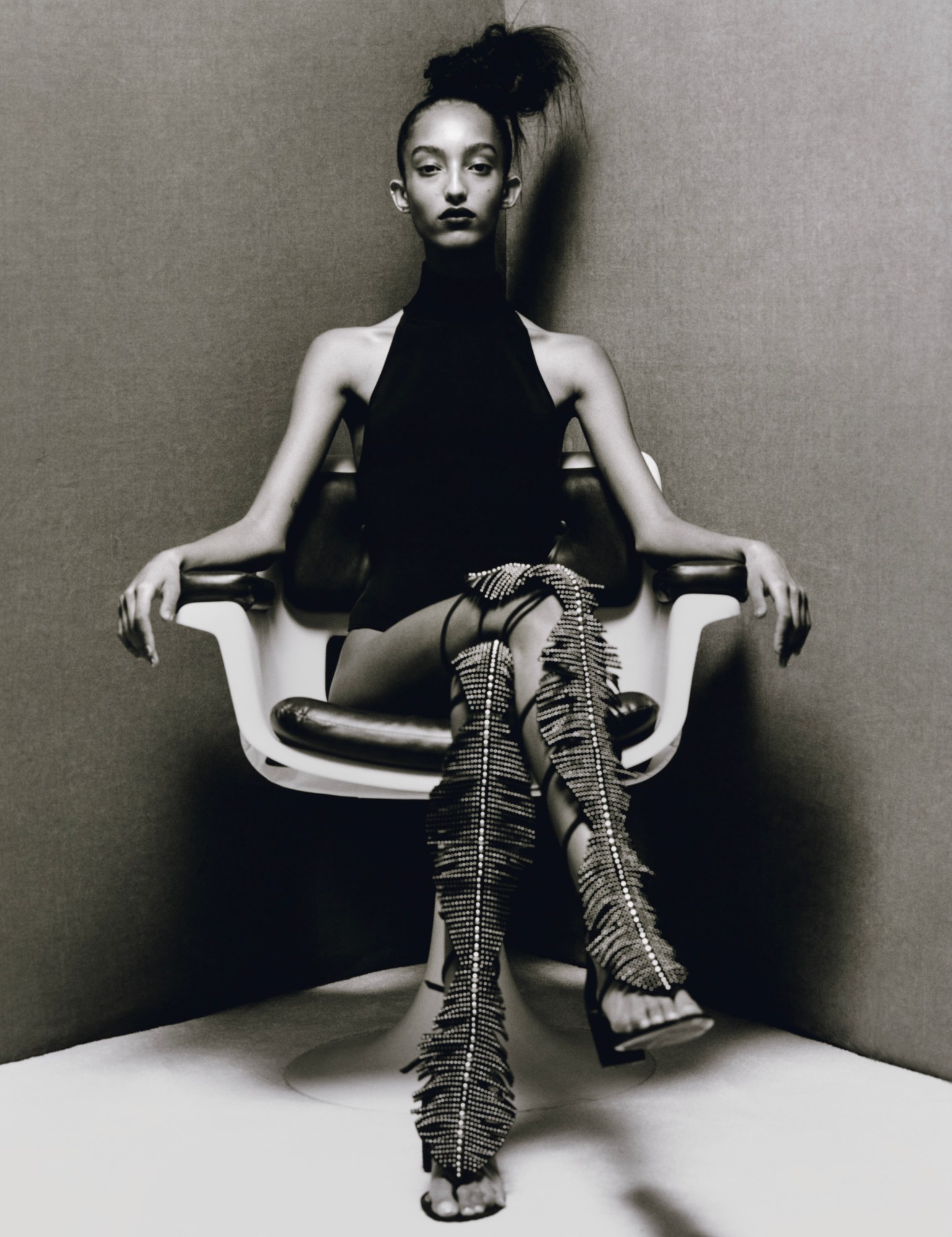

They were clothes that exaggerated femininity into something brazen and bold: “bodybuilders without the gym,” as Ingrid Sichy once put it. And they couldn’t be better fitted for today’s pervasive hyper-exaggerated Cola-bottle curves, or more in tune with the explicit, always-in-control lyrics of Megan, Nicki, Cardi et al. For a generation of women, Hot Girl Summer is not just a season, but a way of life.

At Alaïa, in the decade or so before Azzedine died, the sensuality became more internal and textural, perhaps as a reflection of the women in Azzedine’s life getting older. Yet, in recent years, his earlier, more incendiary work has attracted vintage-obsessed younger women, like Dua Lipa and Kim Kardashian, both of whom recently unearthed 1991 Alaïa leopard-print bodysuits, and bought them for their own wardrobes. Somewhere in the middle, Pieter is trying to find common ground.

“We are the only house that can do sexuality without it being vulgar,” Pieter grins on the day before his show. We’re here for a preview of the new collection. Vivaldi is playing in the studio, which is frenzied with fittings, castings and pre-show mayhem. The clothes were finished weeks ago – there are no last-minute changes being made here – and they’re sexy, entirely fitted to each of the women walking in the show.

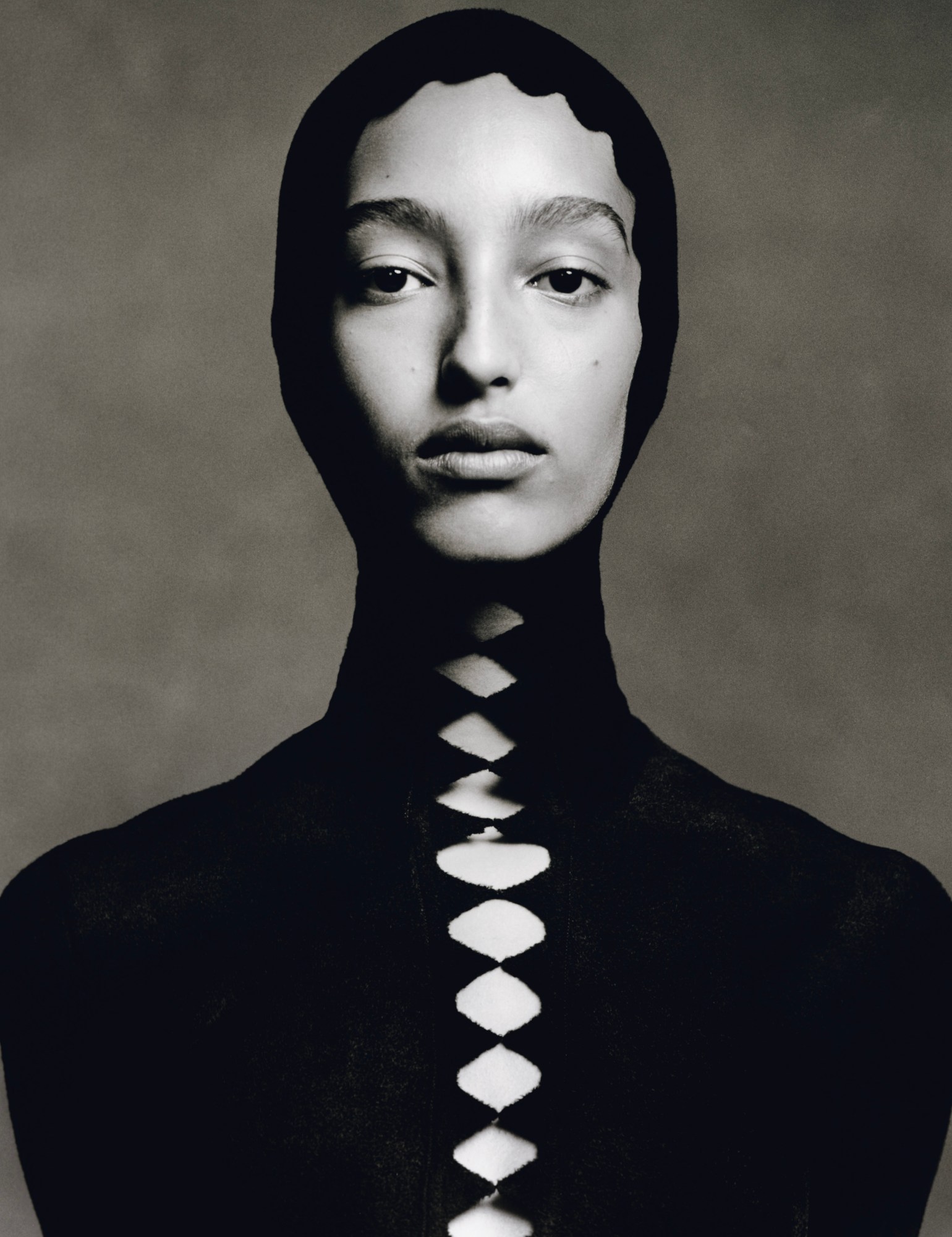

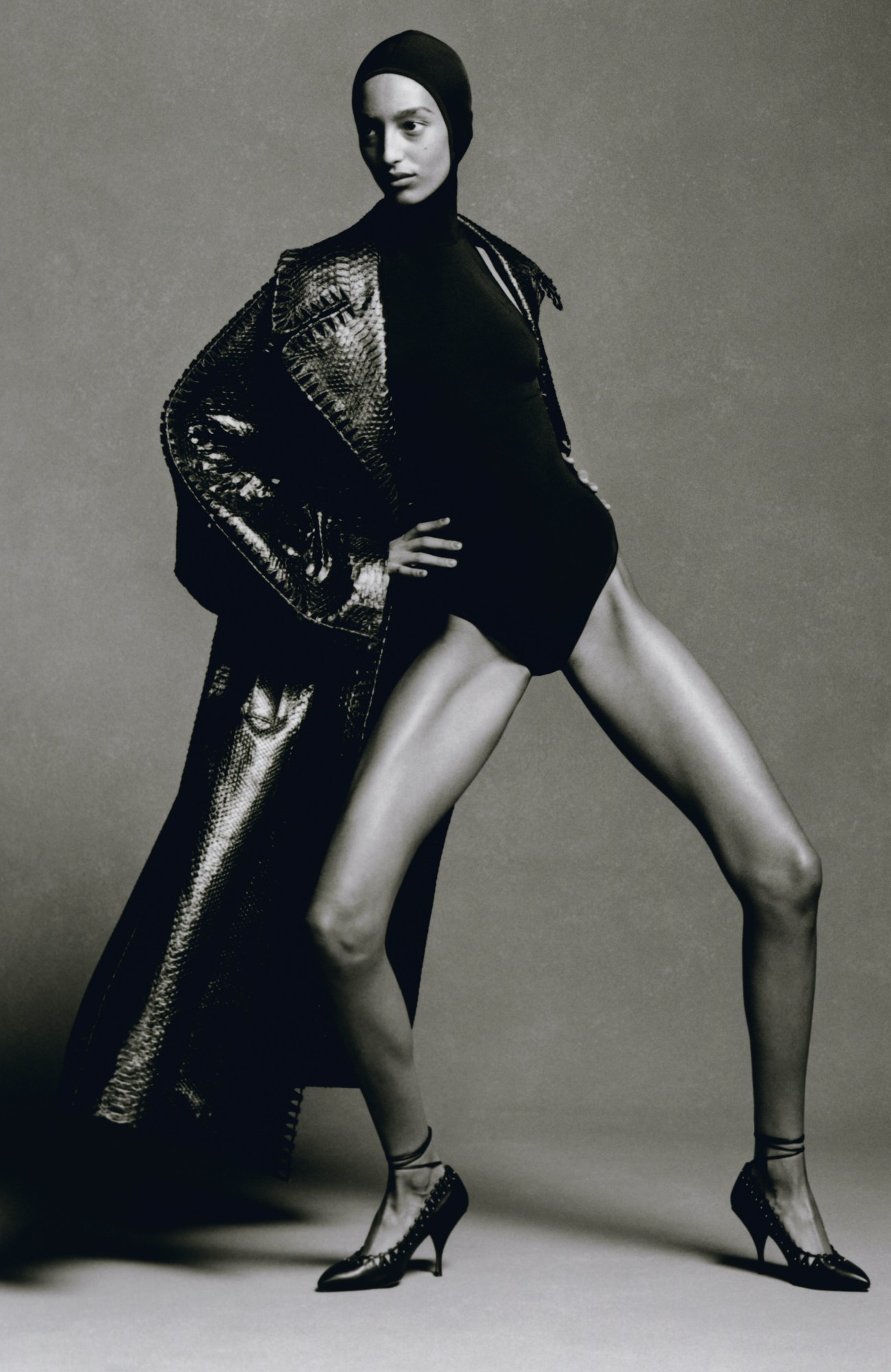

Many of the garments, through couture wizardry, are entirely made with just one or no seam at all, from one piece of fabric, the edges woven like baskets instead of sewn, like the sweeping black python coat, or nappa leather sculpted around the body with fastenings at the back going from top to bottom – the kind of garment that makes getting dressed an erotic act in of itself.

“It’s been a long time since we’ve seen Alaïa so overtly sexual like this, but we’ve tried to do it with Azzedine’s taste level,” Pieter says. He holds up one of the hooded stretch-silk dresses, the aubergine-coloured bodice sensually outlining the torso with an openwork seam, and the skirt ever so slightly transparent.

When I ask him about the veils, he brings his hands to his face. “Azzedine always said there is a beauty about this and a sexuality, too. It’s all about extremes in this collection – you’re either completely covered or completely open.”

This sums up Azzedine’s own approach to sexuality. Growing up in Tunisia, he saw his Muslim relatives wear veils in the streets and parade in the nude at home, and so you can only imagine that years later, when it came to making costumes for the dancers at the Crazy Horse, he individually fitted each of their G-strings with the precision of a couturier, just as he would a coat for Greta Garbo, who requested her navy boiled-wool coat be “big, bigger biggest!”

Religious modesty and French eroticism, the tightrope between sin and purity that defined Alaïa’s extreme silhouettes, are perfectly illustrated by the waist-defining leather corset belts akin to the fretworks of a mashrabiya screen, more likely to be found in Islamic architecture than a nightclub. Given that Pieter hails from Antwerp, it was always going to be a challenge living up to that. Belgium doesn’t have the sensual warmth of the Mediterranean.

But then again, Pieter had a Catholic upbringing and went to boarding school in uniforms ripe for subversion (Azzedine once said of Catholic nuns and Vatican bishops, “The most erotic… sexy to die for!”). And Pieter is the first to admit that Antwerp isn’t the most obviously erotic of cities – “Here, we cover everything up” – but perhaps that also came in handy, considering the several huge Garbo-esque cocoon coats he’s created for the collection.

What Azzedine and Pieter really share is the technical knowledge of sewing, an often neglected skill among designers. Just as Alaïa studied sculpture which emphasised his sense of construction, Pieter initially studied law (his father was a doctor), then transferring to design and architecture at the Institut Saint-Luc in Brussels. By then, he had caught the fashion bug, perhaps without even realising. At 18, he discovered the work of Helmut Lang and begged his mother to take him to the local department store to get a glimpse of the lo-fi T-shirts and straight-up denim that defined an era of cool.

“It was the mid-90s and I had this classic upbringing, but I could still understand what it was because it was still just clothes,” he says. “There was nothing conceptual about it – just about beauty and attitude.” It was heightened when he discovered the Antwerp Six, the designers that put Belgian fashion on the map, courtesy of a teenage girlfriend.

By the time he was graduating in Brussels, he had also come to appreciate the work of a young designer called Raf Simons, who was reimagining the shape of modern menswear with his urban, subcultural-inspired fashion. As it turns out, Raf would end up on a jury for Pieter’s graduation project. “He came to me and said he didn’t think I was made for architecture or furniture, but for fashion,” Pieter remembers, who was unsure at the time. He took his number nonetheless and called him a week later. “He said, ‘Come and work for me.’ A week later, I moved to Antwerp and it changed my life. It was that simple.”

He worked on Raf Simons’ label for seven years, arriving without a morsel of sartorial know-how. “I didn’t know anything about patterns or fabrics. They educated me in everything technical, you know, guiding the pattern makers, going to all the factories. Then after a year, I became his right hand in the studio.”

The learning curve took a turn when Raf was appointed Creative Director at Jil Sander in 2005, and Pieter followed him to Milan to oversee the footwear for the famously minimal brand. Another seven years went by, and Raf – and his team – exited Jil in 2012. For a brief moment, Pieter considered starting his own namesake line, based out of Antwerp.

Funnily enough, the idea was to bring a bit of sexuality to the Northern European fashion scene. He started with shoes, designing the wooden-heeled mules that made an appearance in his debut for Alaïa. Then, suddenly, Pieter’s father became sick. “I took a year off from all of it and I guided him and my family until he died.” Perhaps in need of a distraction, a month after Mr Mulier passed, the phone rang.

It was Raf. “I’ve just signed a contract with Dior. Do you want to come with me to Paris?”

Dior was everything that Raf – and perhaps by extension, Pieter – wasn’t. It’s frivolous and nostalgic, colossal and old-fashioned; most of all, it’s a couture house. Arriving at 30 Avenue Montaigne in the spring of 2012, Pieter was nervous and in a completely unfamiliar environment, as he tells the documentary crew who followed him and Raf during the making of the first couture collection.

But it was les petites mains – the artisanal seamstresses who make a designer’s vision come to life with chiffons, tweeds, tulle, feathers and silks – who had the most profound impact on Pieter upon his arrival. “When I discovered them, I really thought these people are as creative as us because at Dior, the system is – as it is at Alaïa – that you give an idea, or you explain something or you make a sketch, and you explain to them a little bit of what you want, and then all the rest is them putting their heart in it.”

Dior had around 100 of these craftspeople, who would bring a concept to life entirely by hand. Alaïa, by comparison, has 24. Many of them were employed by Azzedine when Yves Saint Laurent shuttered his haute couture business in 2002 and retired from fashion. In recent years, couture houses have capitalised on their craftsmanship with industrial force, with beautifully lit videos of embroiderers and seamstresses pinning swatches in their immaculate white coats. Increasingly, they’ve become the foil for the “behind-the-scenes” videos that one could call “atelier porn”.

“I really don’t care about the 50,000 hours or 10,000 hours of work that goes into it,” Pieter says, with the air of someone who has put them in himself. “I think the idea of couture is completely different. People are not impressed by this anymore. I’m not impressed by it anymore. You know, the concept of our show was to be as simple as possible, without pretension. We don’t need something 100 metres long made by hand and embroidered by 1,000 women for four years. We live in a world of images. I think couture has to change a little bit with that. It’s also the idea that counts.”

Which brings us back to the show on Rue de Moussy.

The Alaïa headquarters are housed in a vast 19th-century converted warehouse in the heart of the Marais, and it is first and foremost a house. Azzedine lived in the residential quarters of the building, which is also home to bustling ateliers, a gallery space, a café, a small hotel, and a boutique with clothes hanging from bronze rails designed by Julian Schnabel and shoes displayed in white Marc Newson cases.

But it was the kitchen that was truly the heart of Alaïa’s maison. It was here that he would gather eclectic circles of friends – artists, writers, thinkers, and the lucky few fashionistas – and welcome them with a quintessential North African sense of hospitality. He would cook simple, elegant suppers that have gathered mythic status, but also stood as an example of a more compassionate, more human way of working in fashion. No starved, tortured genius and his employees. Azzedine was generous by nature, both in his food and the intent with which he made clothes.

You get the sense that Pieter isn’t cooking in the Alaïa kitchen, and that he is far less social in Paris, but he’s generous with his time, perhaps because he’s not used to being interviewed by journalists and schmoozing with celebrities. Instead, he walks to work every day, usually stays late, and then returns to Antwerp every Friday to his boyfriend Matthieu Blazy, who also commutes back from Milan, where he is Design Director at Bottega Veneta.

Post-pandemic, Pieter established a rule for himself that he would no longer work weekends, after years of blurring the lines between work and personal life. He describes his life in Antwerp as “very classic”. “I cook, I invite people for dinner. We go out,” he says. “Antwerp keeps me grounded a little bit, because Paris…”

He pauses. “How can I say it in the most polite way? There’s something about an ‘in crowd’ in Paris that I personally find a bit too much. I am always happy to leave Paris and I’m always happy to find Paris again. My life in Antwerp is the opposite.”

That might be why, in many ways, his first show on the street is a love letter to Paris, to how beautiful it can be on a summer’s evening. And besides, it was meant to feel a bit more “democratic”, as Pieter put it. “That’s why I wanted to bring the show to the streets, it’s for the young kids,” he explains, before adding, with caution but utmost respect, “It has become very ‘salon’ in the last few years, and that can be a bit too pretentious.”

Pieter’s mission is to get 25 year olds lining up to the Alaïa boutiques, just as the most photographed supermodels of the 90s did. Back then, the girls who didn’t get out of bed for $10,000 worked for Alaïa in exchange for clothes to wear out on the town, before being captured striding across Parisian cobblestones by the likes of Arthur Elgort and Peter Lindbergh.

During fittings for Pieter’s collection, Mica Argañaraz burst into tears, which is the kind of emotional reaction you want. Importantly, the new prices at Alaïa are not so eye-watering. Bags will be found for less than a grand, with ready-to-wear starting at half of that. “Even rich people don’t shop the way they used to,” Pieter shrugs.

In the studio, he picks up a pair of half-legging-half-stockings, proclaiming with a wry smile: “Here we have the jegging, the most vulgar item in the world.” Just as Azzedine pioneered his own clinging couture fabrics by mixing jersey and swimsuit materials, Pieter also experimented with materials, developed stonewashed microscopically-knitted denim with a Japanese firm, before weaving them into leggings without a single seam, the three-dimensional shape incorporated into the programme of the knitting machinery,

The most important thing for Pieter, though, is the tailoring. “People often say Alaïa was a dressmaker, but I think he’s a tailor, a big tailor, but nobody knows or they forgot about it.” The slick cigarette-pant suits with blazers with darted seams twisting around the body like invisible exoskeletal structures open the show. Pieter wants to make tailoring just as much a part of the business as its incredible knitted jerseys and statuesque leathers. Ultimately, his first collection is about educating people about Alaïa, excavating its sacred scriptures.

Look closely at the collection and you’ll notice there is also no embroidery, a conscious decision in order to focus on silhouette. The only embellishments are Tunisian bells, jangling on lattices of knits, and micro studs used as if they were the lightest beads. The veils nod to Muslim modesty but also to the sensuality of a covering up while remaining incredibly exposed. It makes the silhouette more dramatic, more erotic.

On the i-D shoot, an evening in Paris after a day of couture shows filled with polite ladylike suits and country tweeds, the clothes come to life. Mona Tougaard writhes to Missy Elliott in a slinky catsuit and stands statuesque in a veiled velvet gown, confidently straight-up in a hooded suit. The walls above the make-up stations are pinned with pictures of Iman, the legendary Somali supermodel who, when once asked what she was thinking of as she swung her hips on an Alaïa catwalk, replied: “Africa!”

Why is this important? One of its most revolutionary qualities is that Alaïa has always been a sacred temple for women of colour, and perhaps one of the only fashion houses in Paris established by a person of colour. Long before words like “diversity” and “inclusivity” were in common parlance in the industry, Alaïa was catering to women who had long been ignored by conventional beauty standards. They flocked to his stores for clothes that enhanced their curves, and in return, Azzedine cast them in his shows and, just as in the case of Naomi Campbell, adopted them as his own daughters and sisters.

“He felt very strongly that all the girls of colour should be given a chance,” Sophie Hicks, the architect who worked for Alaïa in the 80s as an in-house stylist, once told me. “His clothes were all about bodies, so it would be crazy if he shunned them for pear-shaped white girls. He’d go for the sporty Americans and the sexy Black girls who had incredible figures and could walk like anything.”

It’s not lost on Pieter, who cast more than half the show with models of colour. “It’s not because of the current situation, but because this is Alaïa,” he asserts, standing in front of a board pinned with faces including Liya Kebede, Anok Yai, Imaan Hammam and Ugbad Abdi.

“Democratic” is a word Pieter keeps coming back to. Providing he can speak the language of Alaïa, all that he wants is for others to share his intoxication with his predecessor’s work and extraordinary legacy. Sure, Azzedine’s body of work will forever be timeless, but it also needs to feel timely for young women only just discovering their love of fashion and figuring out how they want to present themselves to the world.

He sees his role as a caretaker, not to be blunt – a coloniser, as so many creative directors do. And for anyone who witnesses his show, the word they keep coming back to is “respect.” Not just for Alaïa, but the people who worked for him, and the women who loved his clothes, and will love his clothes.

As his letter to Azzedine concludes: “I wish to live up to your standards. I will take care of your house and your family with a tremendous sense of admiration and responsibility. It’s a dream come true to build the future of this legendary house.”

Credits

Photography Luis Alberto Rodriguez

Fashion Director Carlos Nazario

Hair Jawara at Art Partner for Dyson using Fekkai.

Make-up Cécile Paravina at Bryant Artists using Make up Forever.

Nail technician Anatole Rainey at Premier Hair and Make-up using Sisley Skincare and Cosmetics.

Set design Justine Ponthieux.

Photography assistance Christian Varas and Paul-Antonie Goutal.

Digital operator Nicolas Fleure.

Styling assistance Raymond Gee and Anna Castellano.

Tailor Mikolaj Sokolowski.

Hair assistance Selasie Ackuaku and Jenine Baptiste.

Make-up assistance Beatrice Han Ching.

Production Simon Fuzeau.

Production coordinator Tobias Brahmst.

Production assistance Sarah Bailly.

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING.

Model Mona Tougaard at Next.

All clothing and accessories ALAÏA.