Tom Bianchi got his first SX-70 Polaroid camera at an executive conference in Miami. Not the most bohemian origin story, but then again, the Chicago-born Bianchi was a corporate lawyer. After studying political science in New Mexico, he earned his law degree from Northwestern. He practiced for 10 years and, at the age of 34, made senior counsel at Columbia Pictures in Manhattan. But after traveling to Fire Island, where he began documenting his friends’ and lovers’ lives, Bianchi chose the freebie camera over his hard-earned diploma. (He literally tore it up and pasted its scraps into a painting he debuted at his first-ever solo show.)

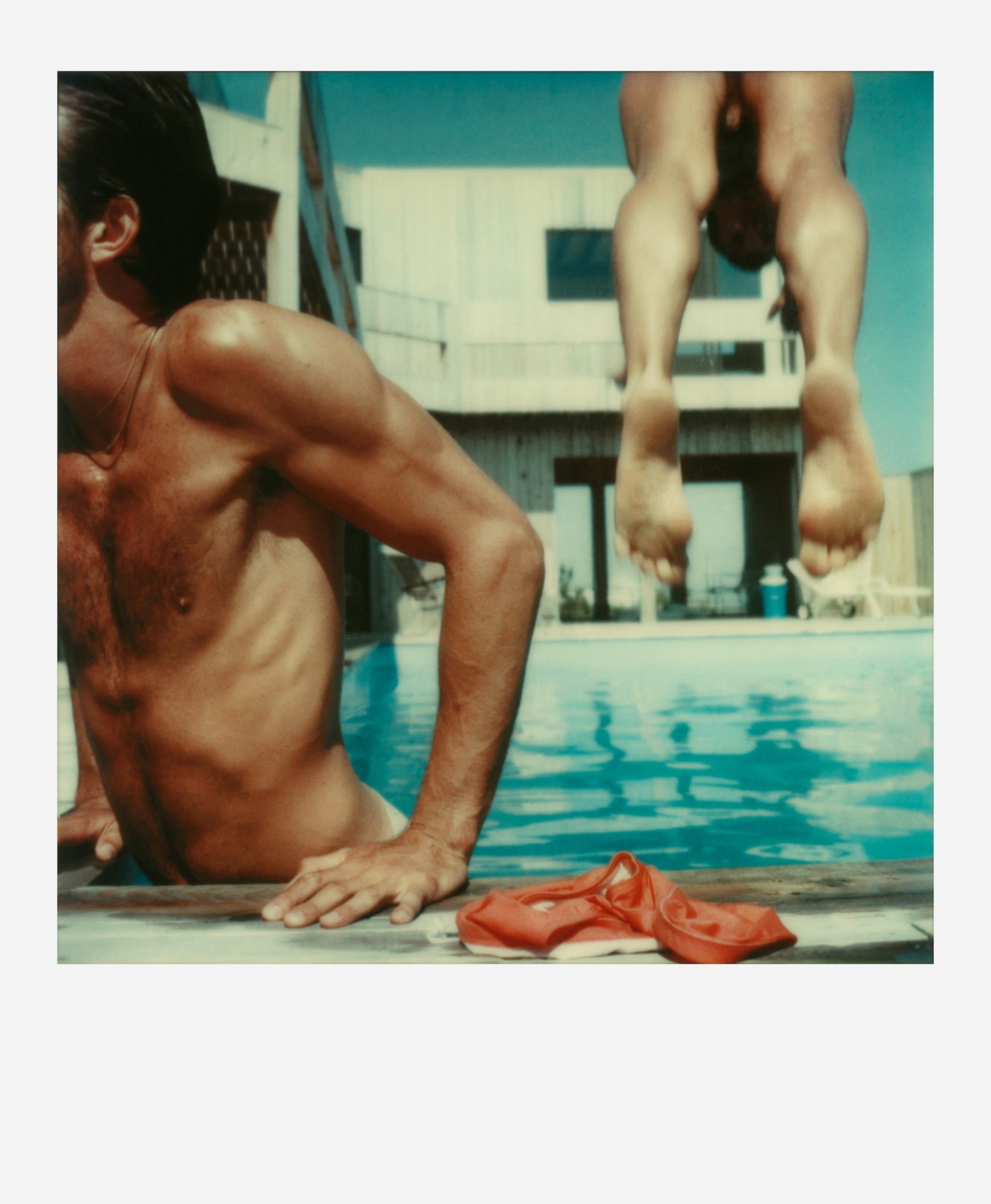

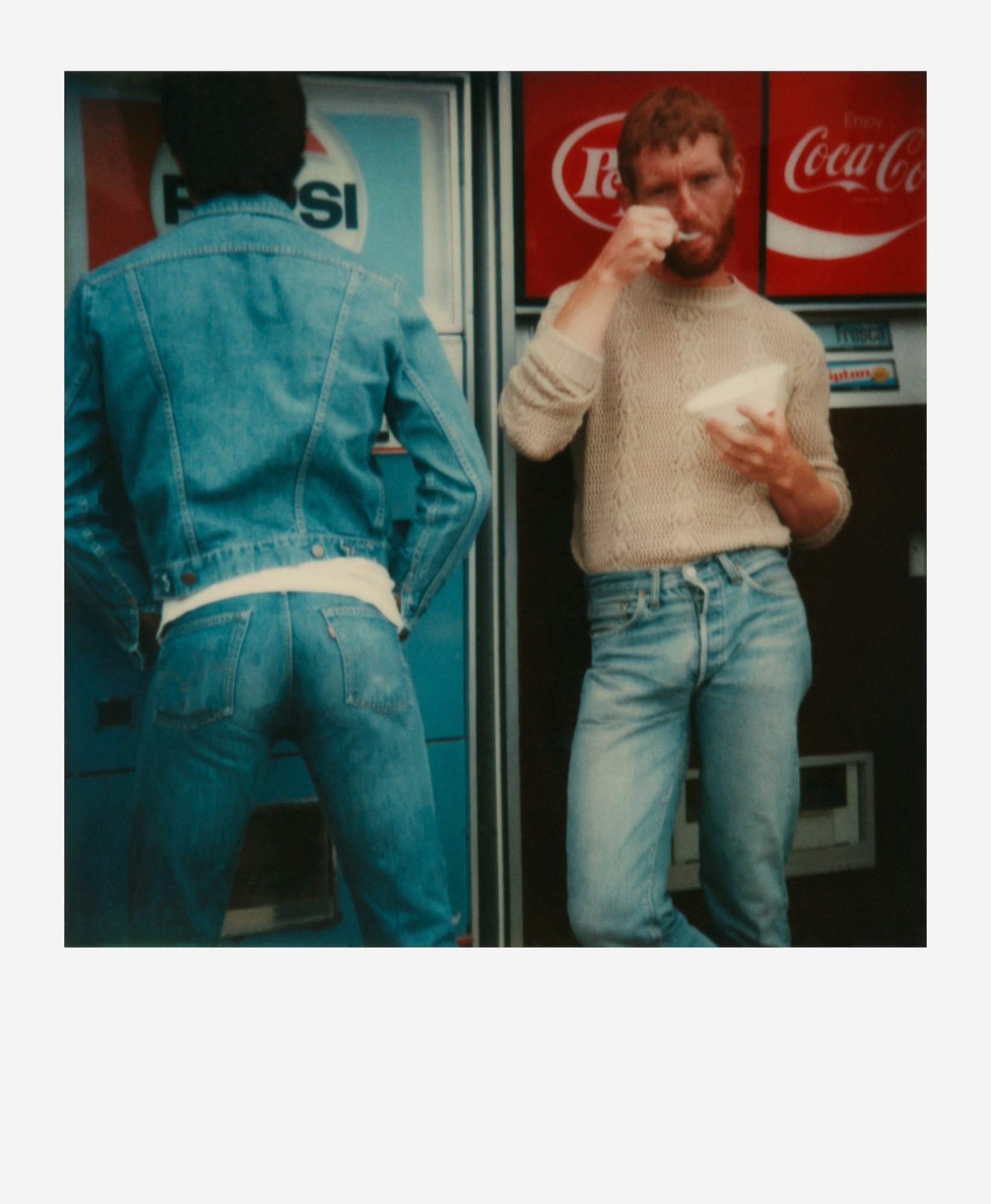

Bianchi’s photographs — collectively titled Fire Island Pines: Polaroids 1975-1983 — form a beautiful, invaluable record of a truly transformative era in queer history. Throughout the 20th century, queer people had been made to hide and hate themselves. In the 1970s, people across the country worked to break out of America’s cultural closet and create new kinds of lives.

“Growing up and coming out in Middle America, you had to imagine a world very different to the one you were living in. The world we were living in disregarded us and called us perverts,” Bianchi told Vice. The brilliance of Fire Island, a 36-mile-long stretch of sun and surf off the coast of Long Island, “was that it was built by those people who imagined a different world and set out to create it. We carved out the tiniest little place just for ourselves, where we could be safe and laugh and play with one another on the beach, and not have any negative judgement surrounding us. What that did was attract the best and the brightest gays from all over America.”

In cities, police regularly conducted raids on bars, bathrooms, and known cruising locations. Being gay could cost you your job, your home, or your life. Fire Island was the first place many queer people were able to feel free — letting loose at afternoon tea dances, sharing showers, partying after sunset, skinny dipping, or simply holding hands on the beach openly for the first time.

Because of anti-LGBTQ oppression, many of Bianchi’s friends and neighbors in the Pines (one of Fire Island’s small villages, separated by sand dunes and connected by a series of wooden boardwalks) were at first hesitant to appear in his photographs. But through the Polaroid’s instant magic, they quickly saw what we do, 40 years later: Bianchi’s reverence for queer tenderness, celebration, playfulness, quiet intimacy, and love.

Bianchi’s book Fire Island Pines: Polaroids 1975-1983 — first released in 2013 to massive acclaim — collects 350 photographs from his 800-plus Polaroid archive. The book also features a deeply moving text Bianchi wrote as a memoir of the era and a memorial for the one that followed: a period of unimaginable fear, confusion, anger, and death resulting from the AIDS epidemic. In addition to his work as a photographer and poet, Bianchi is the co-founder of a biotech company researching AIDS medication.

It’s fitting that a new exhibition of the book’s images has opened at Throckmorton Fine Art during the final days of Pride month. It is in part because of artists like Bianchi, and the generation of men he photographed during Fire Island’s golden age, that queer people radically rejected shame and stigma for self-love and support. “We developed this sense of community and started seeing ourselves as really special people, indispensable to the culture we lived in,” Bianchi said.

‘Tom Bianchi: Fire Island Pines Polaroids 1975-1983’ is on view at Throckmorton Fine Art through September 16, 2017. More information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography Tom Bianchi, courtesy of Throckmorton Fine Art