Global leaders have spent years trying to persuade North Korea to abandon its nuclear program, but their appeals have largely fallen on deaf ears. Last week, however, South Korea unveiled a secret weapon: K-Pop. They’ve tried this tactic before, blasting pop hits across the border in response to a nuclear test back in 2016, but this time actual K-Pop stars — around 150 of them — are being sent to perform in Pyongyang. The aim is ultimately to strengthen relations between the two territories, but musician Yoon Sang admits the cultural mission will likely come with its difficulties: “While we’re on the stage, I believe it will be difficult to portray personal feelings towards denuclearisation,” he said, in what may be the understatement of the century.

While this pop trip over the border may seem surprising, it is actually part of a long history of music being used as a political weapon — both to deliver government propaganda, and drive popular resistance. In South to North Korea case, the K-Pop stars won’t need to make grandiose statements about denuclearisation, because their presence in a country rumoured to enforce strict musical censorship will be a powerful statement in its own right.

The same can be said of the famous jazz ambassadors employed by the U.S. during the Cold War; stars including Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington and Dave Brubeck were chosen to embark on a global tour designed to win new ideological allies. The government’s choice of African-American musicians was also crucial, given the country’s history of slavery and enduring institutional racism. Not only were these men jazz pioneers, they were endearing cultural symbols and supposed proof that the U.S. couldn’t possibly be racist. Though the musicians complied, and led this largely successful bid to diffuse war, Dave Brubeck and his partner Iola wrote a play about the experience, The Real Ambassadors, which highlighted that the men knew they were being exploited for political gain. “Though I represent the government, the government don’t represent some policies I’m for,” Armstrong says in an early interlude.

Despite being weary of their temporary — and ultimately conditional — seat at the table, the jazz ambassadors toured the world because they understood that music could enact change. Like the K-Pop stars of today, their lyrics, melodies and instrumentation became political propaganda.

“‘Protest music’ is a term that gained popularity during the Vietnam War, when public suspicion began to rise that the US government was knowingly sending soldiers to be slain in a war which ultimately couldn’t be won.”

But what happens when music is weaponized against governments? ‘Protest music’ is a term that gained popularity during the Vietnam War, when public suspicion began to rise that the US government was knowingly sending soldiers to be slain in a war which ultimately couldn’t be won. These fears were confirmed by the scandalous 1971 Pentagon Papers, but musicians had been writing about these tragedies years before. “You raise my taxes, freeze my wages and send my son to Vietnam,” Nina Simone sang in 1967’s Backlash Blues. Bob Dylan’s sorrow-laden Blowin’ in the Wind became an iconic lament of wartime violence. And Joan Baez even found herself caught in the middle of a bomb attack, pouring this pain into songs like Saigon Bride: “How many dead men will it take to build a dike that will not break?” These emotionally laden songs mobilised the country’s youth, fueling widespread protest and reportedly nursing the morale of downtrodden soldiers. They’re also credited often with toppling the Nixon regime; despite his short-lived re-election in 1972, protest music helped to mobilise and unite young people against him.

In the UK, musicians continue to speak out about injustice, and especially those affiliated with grime, a genre borne from largely from oppression, resilience and resourcefulness. From Stormzy’s electrifying takedown of Theresa May and her lack of support for Grenfell at the Brits — which provoked an official response — to grime stars’ support for Jeremy Corbyn, a politician who was also invited to address thousands of festival goers from the Pyramid stage at Glastonbury in 2017. Over in the US, there were many artists who forbade Trump to use their music during his campaign; an embarrassment that preceded his desperate, meme-making struggle to find musical acts for his inauguration concert.

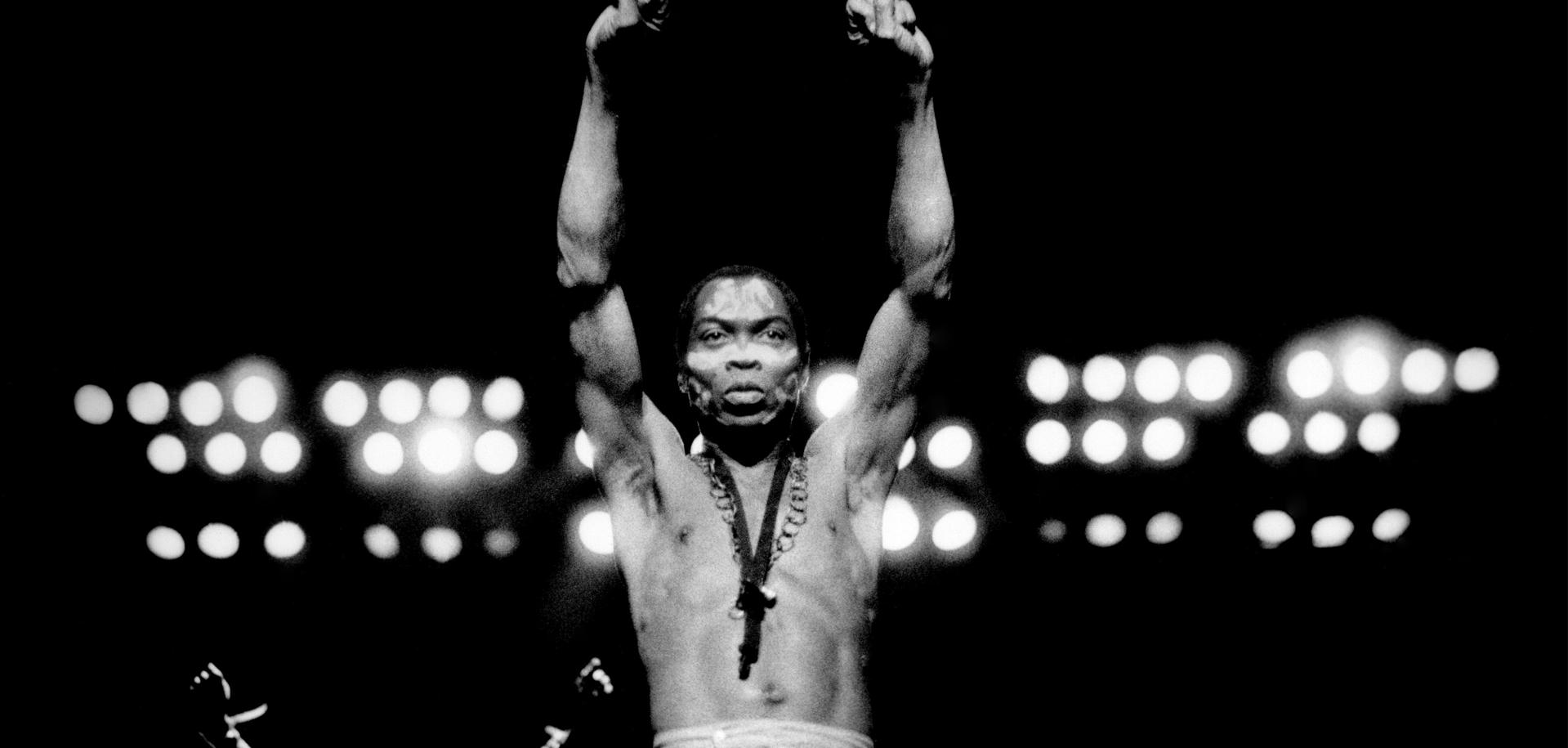

It has become almost expected of UK and US musicians to work politics into their music, but what about those protesting in less tolerant countries? Pussy Riot’s Punk Prayer saw them arrested and sent to remote gulag-like prison colonies. The lyrics of the anti-corruption anthem translate as, “Bless our festering bastard-boss / Let black cars parade the cross.” Presiden Putin said he refused to get involved, but the horrific treatment of the women, who were beaten, whipped and pepper-sprayed, spoke volumes: creative expression through music can still be met with jail time in Russia. Fela Kuti similarly felt the wrath of the Nigerian army when he released 1976 album Zombie, an attack aimed squarely at the country’s government. “Zombie not go go, unless you tell am to go,” he sang, comparing soldiers to braindead morons following orders without question. The reaction was brutal. A thousand fighters stormed his commune, the Kalakuta Republic, destroying his home, beating him viciously and, reportedly, even murdering his mother, herself an iconic feminist activist. Kuti wasn’t posturing as ‘woke’ to build his brand; he literally risked his life to protest an insidious government regime.

It’s unfair to say that musical activism has lost its sting — artists like Anohni, Kendrick Lamar and Stormzy are still taking radical stances with their lyrics — but activism has been co-opted as a trend by pop acts making meaningless statements that look edgy, but are palatable to the establishment and do nothing to challenge the status quo. Real protest music is often ugly. Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit is exemplary of just how haunting, grotesque and unflinchingly visceral songs can be: “Blood on the leaves and blood at the root / Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze,” she sang way back in 1939, depicting a blood-curdling image of racist lynchings. Her words were drenched in pain, whereas the words of Public Enemy were fired by anger: “911 is a joke,” they sang 50 years later, attracting widespread public racism — snippets of which they turned into a series of interludes on seminal album Fear of a Black Planet.

“It’s unfair to say that musical activism has lost its sting — artists like Anohni, Kendrick Lamar and Stormzy are still taking radical stances with their lyrics.”

Groups like Public Enemy and NWA have always been political. Hip-hop has always been inherently political. This is perhaps why recent rap talent competition The Rap of China was met with a blanket ban on the musical genre, supposedly for misogynist lyrics and the promotion of drug culture, in China. Oppressive governments are still afraid of music. They’re scared of its power to mobilise, to unite and ultimately to send an enormous fuck you to corrupt regimes. Ironically, China’s Communist Party had co-opted rap for its own gain just years earlier. In the same way that U.S. politicians celebrated black musicians but continued to ignore the struggles of actual black people, the Chinese government celebrated hip-hop but ultimately cracked down when the people took its power into their own hands.

Radical musicians will generally reject official approval, from the Queen’s Honours to politician’s soirées. “I don’t like acceptance. It makes me think I’ve done something wrong,” Cosey Fanni Tutti said recently. The now-celebrated artist and musician — of Throbbing Gristle, and Chris and Cosey fame — once nearly lost the ICA it’s funding for exhibiting her sex magazine works, and was dubbed along with the band as “wreckers of civilisation” by a Tory MP. Naturally, Tutti was thrilled.

In fact, approval can spell disaster. Band Aid is one of the most famous examples of ‘political music’ precisely because its message was simple, and easy to agree with: we need to feed the world. This sounds rosy in theory, but a far more sinister story was uncovered in a lengthy SPIN exposé. What was meant to be a musician-led political intervention in the Ethiopian famine actually turned out to contribute to hundreds of thousands of murders. The country was in the midst of a Civil War at the time. So the funds, handed over by a beaming Bob Geldof, were actually used by a lethal dictator to carry out widespread slaughter.

Music might be a light-hearted, accessible way to sugar-coat urgent messages in effervescent hooks and saccharine soundscapes. But it is a powerful tool, wielded both by governments or against them. Countless musicians have denounced powerful regimes; and while some find critical acclaim, others — like Fela Kuti and Pussy Riot — are met with state-sanctioned violence, and even murder. Nina Simone famously said that an artist’s duty is to reflect the times in which they live, and — from Billie Holiday’s lyrics about racist lynchings, to Public Enemy’s screeds against institutional racism, and Solange’s exposition of daily microaggressions — many have done. While South Korea’s K-Pop ploy to advocate for denuclearisation may or may not help to push the needle on that issue, it certainly follows Fela Kuti’s assertion that music is a weapon of the future.