Long before Drive My Car, Shoplifters and even Spirited Away, it was the 1950s that marked Japan’s ‘Golden Age’ of cinema. It was a period that saw the major studios strike gold with samurai epics, exquisite family dramas, and even nuclear-powered dinosaurs. But when audiences began to dwindle in the ‘60s (just as the French nouvelle vague transformed global perspectives of what cinema could be), Japanese cinema underwent a metamorphosis — with a new generation taking a turn for the experimental.

The Japanese New Wave was led by new, young directors like Nagisa Ōshima (In the Realm of the Senses) and Kijū Yoshida (Eros + Massacre) — who took influence from European auteurs like Godard and Antonioni as they began deconstructing established cinematic style and form. Their films, often riddled with controversial subject matter, provocative imagery, and total disregard for narrative convention, quickly proved far from commercially viable — and so, by the early ‘60s, many directors split from the studios in search of alternative means of funding.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

In stepped the Art Theatre Guild (ATG), one of the great catalysts for the development of Japanese arthouse cinema; an alliance of ten national cinemas, founded in 1961, that saw value in hyper-creative and challenging works. They began distributing the new Japanese cinema all around the country alongside foreign media by Tarkovsky, Bergman and Buñuel — and by the end of the decade, they were funding and producing all kinds of iconoclastic, low-budget films. The ATG no longer exists — operations ceased in the ‘80s — but its influence can be traced to all kinds of independent filmmaking in the present.

And while countless classics of the Japanese New Wave — including those produced or distributed by the ATG — remain frustratingly inaccessible in the West, the tide is gradually turning thanks to distributors such as Criterion and Arrow, and streaming platforms like MUBI. With a trilogy of ATG-powered masterworks arriving on the latter this month, i-D jumps into the artistic zenith of the Japanese New Wave below.

The entry point is… This Transient Life, 1970 (Akio Jissôji)

For a long time, Akio Jissôji was better associated with TV sci-fi productions like Ultraman rather than experimental, avant-garde cinema. But that changed in 1969 when he began collaborating with the ATG on a series of radical arthouse films — including a trio of monumental and sexually transgressive works retrospectively dubbed ‘The Buddhist Trilogy’.

The first of these was Akio’s controversial feature debut: This Transient Life. The story of a passionate, incestuous relationship between a sculptor’s apprentice and his soon-to-be pregnant sister, it’s made even more sacrilegious by the fact that the film takes place almost entirely around a Buddhist monastery — with religious philosophies and ephemera a major focus.

While riddled with racy sex scenes, orgasms, voyeurism, and copious shots of the naked human form, the film is considered a masterwork due to its impressive artistic vision — which helped it take home the Golden Leopard at Locarno Film Festival in 1970. Formal highlights include elaborate tracking shots, intrusive close-ups, and an experimental shot composition that frequently pushes the action into the corner of the screen. The surreal finale, meanwhile, involves a giant fish.

Streaming via MUBI and available on home media via Arrow.

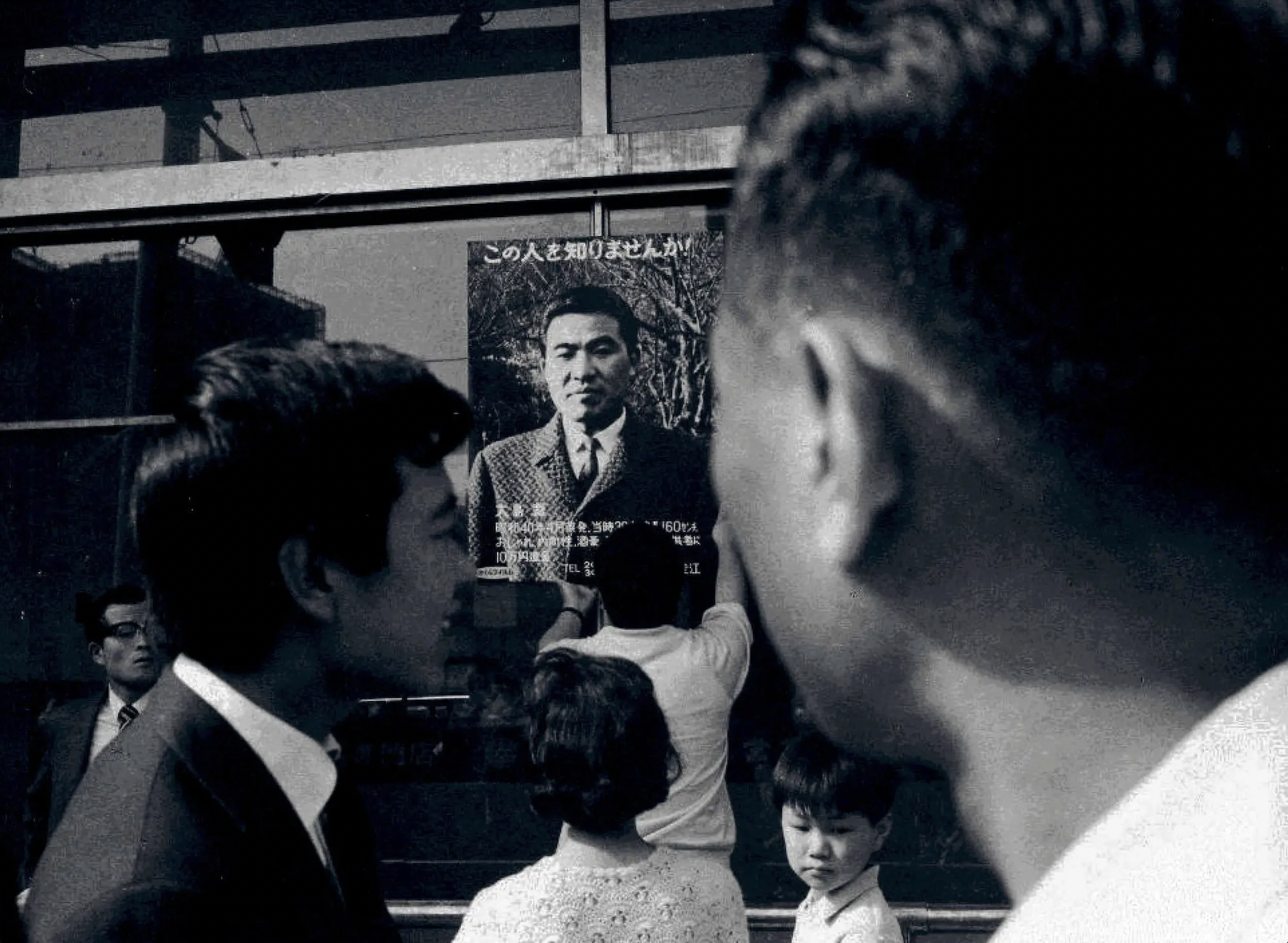

Necessary viewing is… A Man Vanishes, 1967 (Shōhei Imamura)

Whereas This Transient Life would showcase a bold new style of narrative filmmaking, A Man Vanishes — the first film to be co-produced by the ATG, in 1967 — instead subverted the documentary format. The blurring of these two forms would be one of the more identifiable characteristics of the Japanese New Wave, a movement otherwise difficult to define in terms of style and philosophy.

A Man Vanishes opens with a missing person’s report: Tadashi Oshima, a 32-year-old plastic salesman from Tokyo, departed on a trip to Fukushima one day and never returned. The mystery of his disappearance is the film’s main concern — and so the filmmakers set about conducting a string of interviews with people who knew him.

A few theories emerge: he may have been embezzling money from his employer; he may have been having an affair. Tadashi’s fiancée becomes a subject of fascination as the filmmakers come to consider her a person of key interest and speculation. But as the exposition piles up, the film drops a twist that throws the entire production into serious doubt.

Is what we’re watching fact or fiction? Is it something in between? These are the questions director (a two-time Cannes Palme d’Or winner in his later career) asks of the viewer, in what ends up being a postmodern subversion of the entire cinematic form. It’s gripping from start to finish, whatever the answer.

Streaming via Apple TV in the US.

The one everyone’s seen is… Funeral Parade of Roses, 1969 (Toshio Matsumoto)

While it would be bold to assume that any ATG-backed Japanese New Wave films have fully perforated the mainstream lexicon, Toshio Matsumoto’s groundbreaking 1969 pseudo-documentary Funeral Parade of Roses — arguably the greatest queer film in Japanese cinema — is one of the most well-known.

Mixing fictional narrative with documentary style and form, Funeral Parade of Roses tells the Oedipus Rex-inspired story of a transgender woman named Eddie (played by the mononymous, androgynous icon Pîtâ) as she descends into the neon lights of Tokyo’s heady gay district in Shinjuku.

Moments of surreality and erotic homosexuality are interlaced with psychedelic music and marijuana smoke — but it’s the giddy, handheld camerawork and experimental editing that makes the whole thing so vivid. The aesthetic would prove highly influential — with Stanley Kubrick appearing to appropriate several scenes for his own dystopian youth drama, A Clockwork Orange.

Streaming via Prime Video and available on home media via BFI.

The under-appreciated gem is… Diary of a Shinjuku Thief, 1969 (Nagisa Ōshima)

Those looking for a clear bridge between the French nouvelle vague and the Japanese New Wave could do worse than to start with Diary of a Shinjuku Thief. It is the most Godard-ian work of distinguished filmmaker Nagisa Ōshima — whose juvenile delinquency films in the early ‘60s helped to catalyse the movement as a whole. (He’d later be sued for obscenity for shooting unsimulated sex in 1976’s In The Realm of the Senses — before directing David Bowie in 1983’s Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence.)

Diary of a Shinjuku Thief is a disorientating tale of two kids gone wild in the Tokyo youth epicentre of Shinjuku. It’s full of jerky camerawork, erratic editing, and random inter-titles that give updates on the time and weather. It’s also preoccupied with sex — and features several steamy and passionate encounters. These various aspects have drawn criticism from some corners — it’s true that the film is a bit of a mess. But these facets are also what make the film such a thrilling viewing experience.

In 1970, Nagisa would describe Diary of a Shinjuku Thief as an attempt to “capture the dynamics of a changing real world and people”, which goes some way to explain the imbalance between style and story. Either way, it makes for an excellent double bill with another classic of the era that remains frustratingly elusive in the West…

Streaming via Criterion Channel in the US.

The deep cut is… Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets, 1971 (Shūji Terayama)

Despite widespread acclaim, the fact remains that Shūji Terayama’s masterwork Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets has yet to arrive in the West via streaming or home media. It’s an affliction that applies to many creative highlights of the Japanese New Wave — but it’s particularly regrettable in this instance due to the film being one of the most visually exciting and artistic works of the era.

Like Diary of a Shinjuku Thief and Funeral Parade of Roses, this is a sexually-charged coming-of-age story set in the cosmopolitan playground of Shinjuku. The plot revolves around Eimei Kitamura (Hideaki Sasaki), whose rebel-without-a-cause philosophy is detailed directly to the audience in the opening scene — where he breaks the fourth wall to speak about cigarettes, factory jobs and a Korean daredevil with a flying machine.

As the film goes on, we observe his sexual awakening; a series of football games; a penis-shaped punching bag; a horrific gang rape; the burning of the American flag; chalked protest slogans; a series of rock musical interludes; and several shots of people pissing in the streets. But the most powerful aspect of the film is its mesmerising use of bright colour filters — with shocking pinks, radioactive greens, and hellish reds creating some unforgettable images.

It all ends with a quote that embodies the forward-thinking mentality of the Japanese New Wave’s innovators as well as anything. “Goodbye cinema!”, the people scream, as the credits begin to roll.