There are few life-stories out there as punk as Jordan’s.

Hailing from Seaford, on the south coast, Pamela Rooke, who took the name Jordan at 14, trained as a ballet dancer throughout her childhood, before becoming an avid David Bowie fan — dressing up and hanging out at the gay clubs of nearby Brighton or London. By the mid-70s, she gravitated to the capital and began working in Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s ground-breaking boutique, SEX, then Seditionaries and, later, World’s End, each of these successive Westwood-McLaren retail incarnations being located at 430 Kings Road.

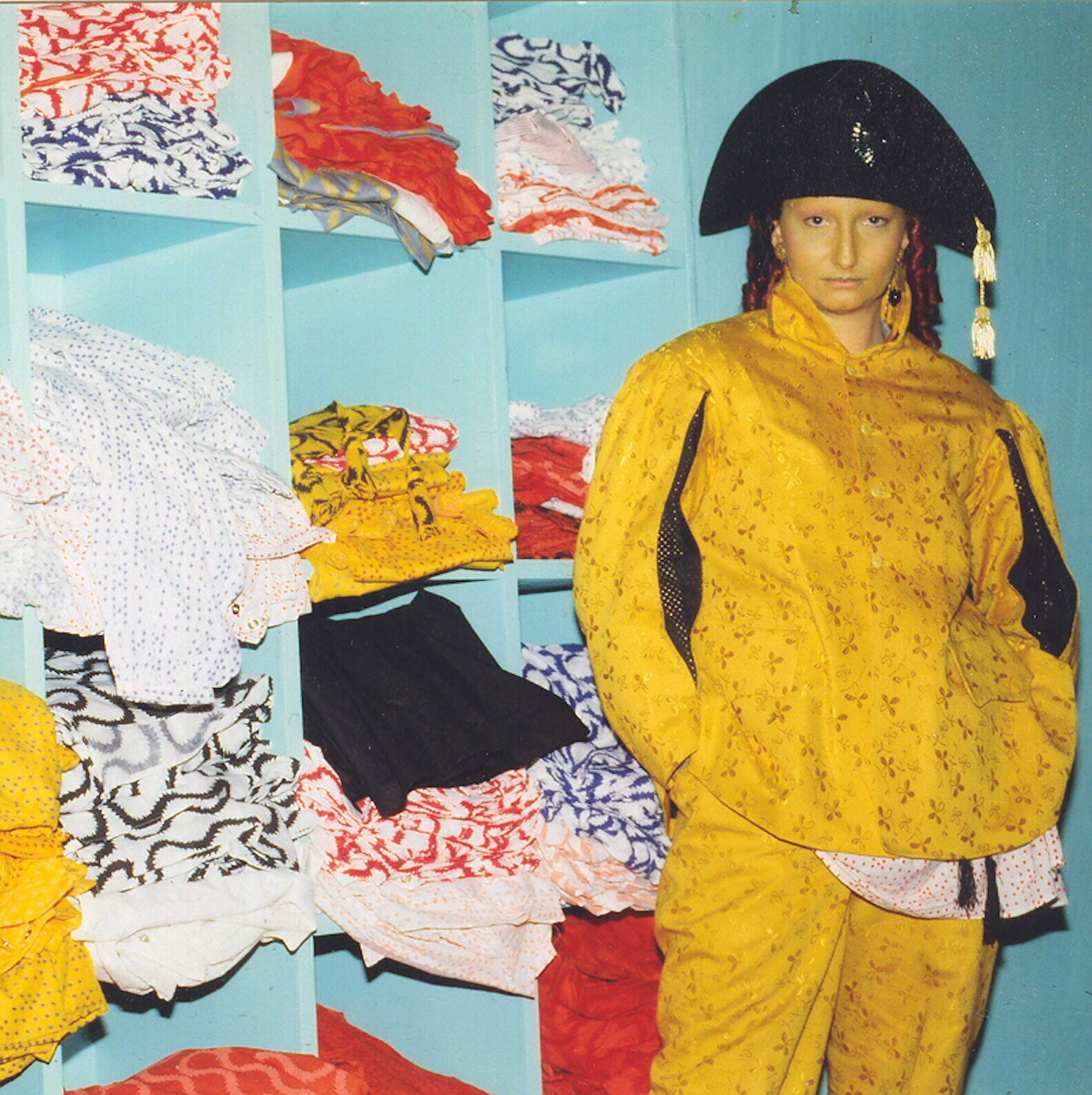

Jordan was a true innovator — fearless and intelligent. She wanted to be her own work of art and never compromised. In fact, her looks were so extreme during the latter half of the 70s that she was routinely moved by train staff into a first class carriage on her daily commute from Seaford to London, to protect her from the outrage and violence her appearance provoked from other passengers. Quite simply, no one else then dared to strut the streets in black rubber fetish-wear, or see-through clothing with nowt underneath, topped off with a towering peroxide hairdo and thick black eye make-up (two decades before Madonna brought S&M-inspired style to the masses with her 1992 photographic book Sex). Jordan’s courageous attitude and trail-blazing image made her the perfect figurehead for Viv and Malcolm’s confrontational fashions and placed her at the epicentre of punk rock mayhem unleashed upon the nation by the Sex Pistols (who were managed by McLaren). In the ensuing decades, every punky-looking girl has owed a debt to Jordan, for paving the way, even if they didn’t realise it…

By the early 80s — having starred in Derek Jarman’s film, Jubilee, hobnobbed with the likes of Andy Warhol and David Bowie, popped up in early issues of i-D mag, shared a flat near Buckingham Palace with a professional dominatrix friend and Sex Pistols’ lead singer Johnny Rotten, as well as managing Adam and the Ants (who went on to become one of the biggest UK pop sensations of the decade) — Jordan got married, then, alas, gradually succumbed to a serious heroin habit, before fleeing back to Seaford. She conquered her addiction and embarked on a successful new career, breeding Burmese cats and working as a veterinary nurse, which she still does to this day.

Until recent years, Jordan generally avoided the limelight and very rarely talked to the media about her past. Now, Defying Gravity, her long awaited autobiography, written with the author Cathi Unsworth, has finally arrived and paints a vivid picture of a life punctuated by pushing boundaries, provoking outrage, punk rock and pussies galore.

What prompted you to work on Defying Gravity?

I’ve been asked several times in the past to write a book, but I thought it would be too self-indulgent. There were two things that made me think the time was right — one was the beautifully curated Punk 1976-78 exhibition at the British Library in 2016, which made me realise how many people were truly fascinated by the crazy freedom of that time and my part in it. Also, in 2015, I sold some of the very old and iconic clothes — at auction — that I had from that time, which had been in a cupboard at home for years. I wanted to make sure they would be preserved, really, because there’s no point in them sitting in a cupboard, getting sadder and sadder. The last time I’d worn the Venus top [an extremely rare Westwood/McLaren piece from 1971] which went for many thousands of pounds in the auction, was back in 1985 at Live Aid! I had no sadness about selling them — I felt I was doing the right thing and real proper collectors and museums would have them and they would be taken care of and people would enjoy seeing them.

You were clearly very into clothes from a young age — where did that interest in image and appearance come from?

I don’t really know where that came from, it was an instinctive thing, but I guess learning to dance opened up my world. I adored ballet, it gives you a strict basis to your life, it opens you up to costumes and fantasy, moulding yourself into something else. It teaches you to overcome pain and fatigue and to try and excel and do your very best. And probably even before that, I always knew what I wanted to wear — at primary school I was known for my little fluffy dresses. There’s a picture of me in the book, when I was a child, wearing a little bridesmaid dress — and showing my knickers, even then!

Did your teenage visits to clandestine gay clubs in 1970s Brighton and London accentuate your growing interest in style? And do you think gays were pivotal to punk’s emergence?

Very much so. That’s where I cut my teeth and began to enjoy social dressing up. At school I was laughed at, basically, because nobody could understand why I would have my hair cut really short, or have different colours in my hair. The gay clubs at that time were mostly male clubs — there weren’t many female gay clubs in Brighton then. The gay male friends of mine who I met along the way opened my mind to different types of music, different types of interaction with people… you could dress any way you liked and never feel uncomfortable. In a way, it was a bit like what punk — for me — stands for, which is to be all inclusive. I was allowed in those clubs, even though I was a woman.

Was it important to you that Defying Gravity acknowledges how significant women were in the punk scene?

Very important. Punk was a time when women had an equal status. Everybody shared each other’s clothes, each other’s make-up. The lines were very blurred between male and female. Women could join bands, they could just pick up a guitar like the boys did and just get on with it. Artistically, women blossomed at that time and really spread their wings.

You wore some jaw-dropping looks, prior to and during the punk era, which must have caused lots of attention on the streets…

Down here in Seaford it was very difficult, there were many occasions where I had big trouble with people who felt I was being obscene, and didn’t understand why I looked the way I did. On the train from Seaford to London I had occasions where people got violent with me. I thought once I’d moved to London and lived there it’d be easy, but it wasn’t really. You’d still have the men on the scaffolding wolf whistling and thinking because you’re dressed like that you are easy game for them. And I also got the opposite reaction — people being very frightened of how I looked, because I was challenging normality, challenging people’s view on sexuality, and doing it deliberately, not as a sex object but as someone who knew where they stood sexually. It was an empowering sexual look. I just felt very comfortable and secure in myself. I look back on that time and think its quite surprising that I never got arrested, because there were a lot of times when I was walking about with very few clothes on! I loved the way I looked and rejoiced in it and I didn’t care what other people thought. I got chucked out of school when I was 14 because of the way I looked — my headmaster was really worried that people at school would start to copy me. I had to explain to him very carefully that people are not going to copy me, because they are actually all laughing at me!

People have talked about how terrifying it was to go to SEX or Seditionaries…. mainly because they were scared of you! What was it like there, for the first time visitor?

You couldn’t see through the window, from outside, as it had frosted glass like at a dentist surgery. The shape of the shop was like a dark long corridor and then at the end of it would be me, standing there, looking intimidating, with my bouffant hair and dark make-up, in front of a big rubber curtain, and behind that was a very small dressing room. It all looked a bit sado-sex, and it certainly wasn’t a place where we would say, ‘Hello, can I help you?’ I hated that sort of thing! Also, we really cared about the craftsmanship of what we were selling. I know people moaned about the price of the clothes, but Malcolm and Vivienne never cut corners. If they wanted a certain fabric or button, they would go to the end of the earth to get it. We would interrogate customers, sometimes, because in our view they were buying a work of art, something they should treasure. We didn’t really like people who came in and had a load of money, but just looked like a clothes horse. We would rather talk to people on the level of, ‘Why are you buying this? What does it mean to you? How would you like to wear this? There’s lots of ways of wearing this, let’s show you.’ So it wasn’t just shoving something in someone’s hand and taking the money. I’d much rather give the odd thing under the counter, or knock a few quid off the price, to someone who had travelled a long way to get to the shop, but didn’t quite have enough money to buy something. I’d give it to them for what they could afford to pay. Because it really meant something to them and they would look better in it, more than someone who was just buying it to be fashionable.

It was quite shocking to read in the book that Vivienne sacked you in the early-80s because you got married! Are you still mates with her?

Yes, we did long interview with her for the book. We spent four hours together and had a great time. I do laugh about it now, seeing as she has been married twice! I can see her point of view at that time. It has been mooted that, at the time, she didn’t want me to get married, as she was concerned I would then be off, somewhere else, doing other things, which is exactly what did happen after I got married! She phoned me up years later and asked me to go back and work in the shop, saying everybody was ripping her off and she needed to have someone there who she could trust.

Punk is a subject that’s been explored in endless books, films, documentaries and magazines, as well as PHDs and dissertations at colleges… there are so many interpretations of it. You are one of the true punk originators — so, how do you define it?

I think it was born out of a particularly bad time in history, where young people used their bodies and their actions to change things. They used their hands for music, or to create fanzines, they got out and did things because they were unhappy with how they were living. So it was an action time where people took their futures into their own hands.

How can young people today tap into the sort of energy that characterised punk in the 70s?

I have met a lot of young people who I have talked to at great length. People have stopped me in the street, for instance, or people who are doing projects for university or college will contact me. But the political and social background back then is so different to today… unfortunately, conforming is generally very important today, it seems. The lines between what mums and dads and children wear is blurred — I wouldn’t have wanted to be seen dead in the same clothes as what my parents wore! There is too much marketing and branding. But also, it’s such a shame that there is no affordable housing so that young people can leave home and be independent. It’s not good for someone who is, say, 35 to still be living with their parents. People used to live in squats and stuff in those days — that gave them great independence to do whatever they wanted. Activism is the way to go now. I agree with Vivienne that people need to be looking forward to the future of this planet. And I think the main thing is to have your own identity — people don’t always realise how empowering that is. Don’t just follow a trend. Don’t be afraid. Make your dreams into a reality.

‘Defying Gravity – Jordan’s Story’ by Jordan Mooney and Cathi Unsworth, published by Omnibus Press, is out 25 April

Credits

Images Michael Costiff archive