This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Summer! Issue, no. 372, Summer 2023. Order your copy here.

When the subject of surfing comes up, the images that populate most people’s brains are beaches in Southern California, Hawaii, or the shorelines of Senegal: locations that offer sunny and warm weather year round. The upper half of the US East Coast rarely comes to mind, considering that half of the year the weather forces its citizens to wear thick down coats and drink exorbitant amounts of coffee throughout the day. But against common knowledge, people in that region with access to beaches like to enjoy catching waves as well. The issue is that, in order to tame those waves, one needs access to a significant amount of disposable income; the average board costs more than $500. Because of that, the common portrait of a surfer is that of a white man. A group in New York’s Far Rockaway neighbourhood in the borough of Queens – which has been home to a majority Black population in recent decades – is actively pushing against inequality on the waves.

Since 2018, the non-profit Laru Beya collective (which translates to “on the beach” in the Indigenous Caribbean Garifuna tongue) has committed itself to empowering Black and other POC youth in Far Rockaway to engage with the water they’ve grown up with through surfing – particularly as gentrification begins to ravage the beachfront neighbourhood. You could say that the collective’s eyes are set on representation and you wouldn’t be totally wrong: it is important for a young kid to see non-white faces gliding through the ocean. But Laru Beya is facilitating something more grand by giving a group who are being actively displaced the tools for survival.

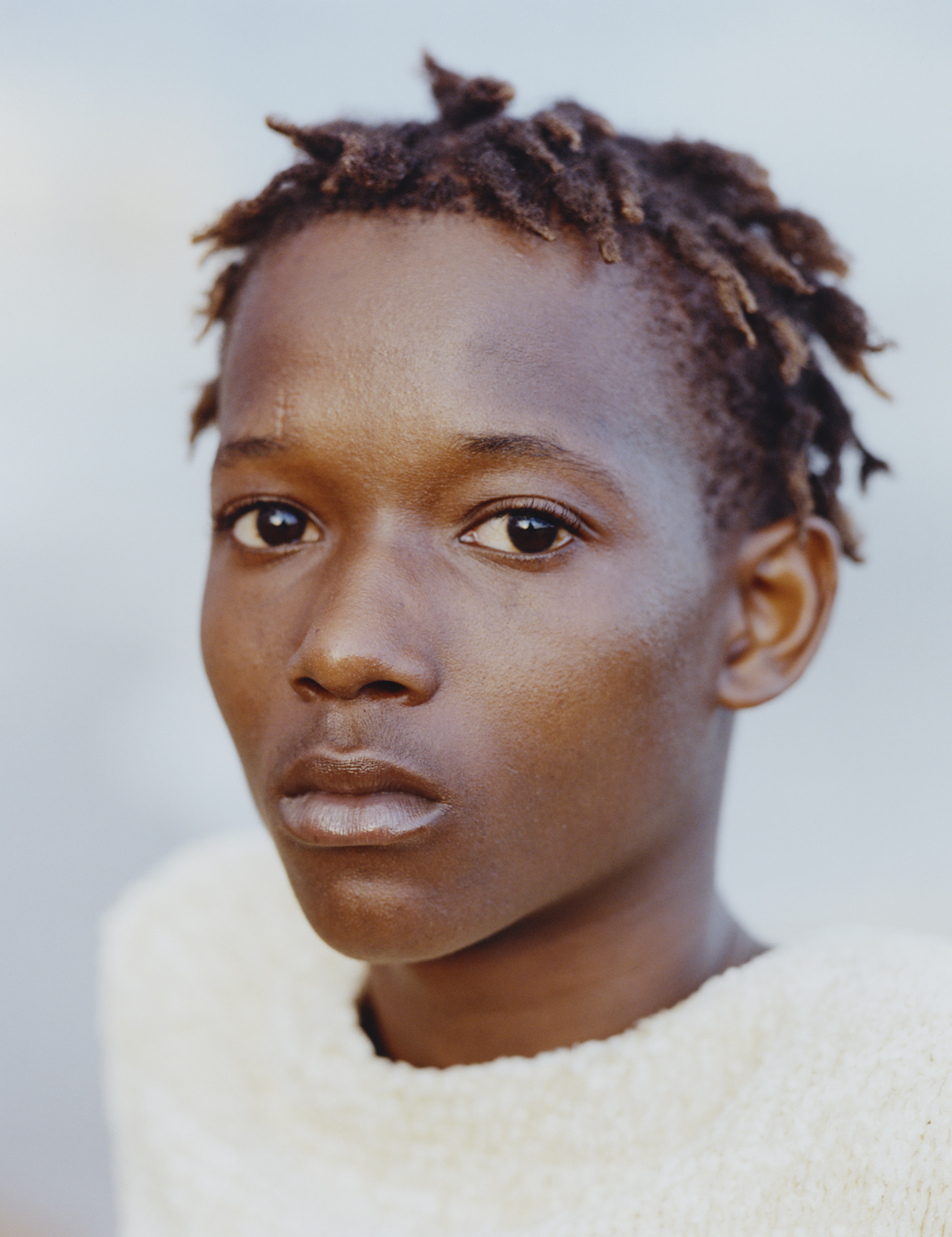

“Surfing was never on my mind before I started,” says 21-year-old Farmata, affectionately known as Farmy, who is a mentor for Laru Beya. “I grew up by the beach in Far Rock my entire life and I would go there in the summertime. My family had picnics here and there.” That’s what the beach provides for most Black families in the neighbourhood: a nice, breezy setting for an outing on a beautiful day. Surfing happened by pure chance for Farmy. “I was part of an internship and they’d take us to fun activities. One day, they took us to a surfer camp in Far Rockaway and I loved it so much I posted about it on social media. From there, a friend invited me to come surf the very next day and that’s where I met a lot of OG girls from Laru Beya. I’ve been doing it since then.”

Farmy, unsure of where life would take her outside of maybe going to college and living the cookie-cutter life that society predestined her for, was transformed by what she experienced as a sixteen-year-old mentee in the collective. A first-generation child of Senegalese immigrants who’s lived in Far Rock her whole life, she’s keenly aware of the racial and socioeconomic disparities at play. Laru Beya has given her a role in combatting them. “There are only two pools that people know about in the community. All of the other ones are private,” she explains. “There’s no space for kids and adults to learn how to swim. Every year there are so many drownings in Far Rockaway, and it’s usually children because we’re not taught about rip currents. As a child of colour it’s usually football or basketball you’re made to be interested in but when you have the beach in your backyard the options are endless.”

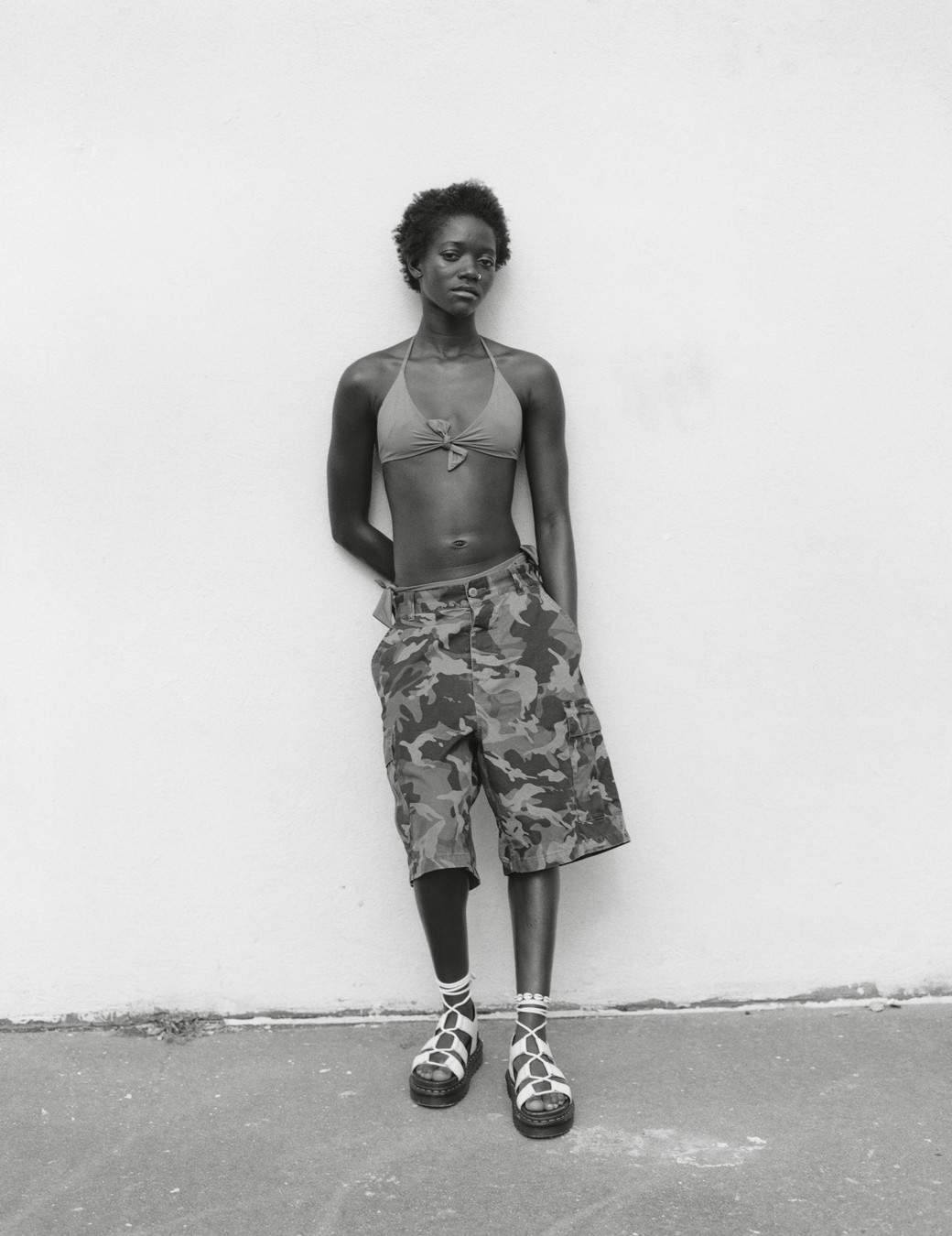

Devaughn, a seventeen-year-old obsessed with skateboarding, and whose family moved from Brooklyn’s Flatbush section to Far Rockaway, can speak to the power of surfing as a means of healing and freedom. “When I moved here I had to surf; we had such a large body of water near our house that I had to do something with it,” he says. “There was one day when I didn’t feel like skating so I went to my local surf shop and they let me take out a board for free. Surfing is good to let some steam off because it’s a way to be alone in a space. Sometimes skate parks are too crowded, but with the water, it’s so huge that you could pick a space where you want.”

That freedom has attracted non-natives as well. 27-year-old Cristina Wright is a photographer originally from the Myrtle Beach area of South Carolina where, like Farmy, the extent of her beach-bound childhood activities revolved around intimate family picnics and cookouts. The water attracted her, but she was an anomaly among friends and family; no one else around her was as comfortable with the ocean as she was. Once she moved to New York after college, she leaned further into her interest. “I was intrigued by surfing in New York because it seemed accessible,” she recalls. “I had a roommate whose brother surfed and I made him take me out one time and once we went I thought, ‘This is hard, I’m not even sure if this is something I can do.’ But as a documentarian, I just wanted to photograph people that were out there.”

While at the beach one day, Laru Beya’s founder, Aydon Gabourel, walked up to Cristina and asked if she had any interest in surfing, and she took him up on the offer. But even more than surfing, she feels gratified paying it forward to the young kids in need of mentorship. “To know that there are so many kids who live, like, a block away from the beach but don’t know how to swim or are terrified of the ocean made me want to get involved,” she says. “Laru Beya provided this anchor. I didn’t see myself being a beach person living in New York, but it’s grounding from a sense of community: having people to call on when you need something, and being a mentor to these kids. I always see myself in their place, wishing I had a mentor growing up.”

Like much of New York City, Far Rockaway is scheduled for immense change. Those changes are already happening gradually: areas around bodies of water – especially where populated by non-white citizens – are targets for redevelopment. Luxury apartments, expensive hotels and chic bars are starting to line the beach and Farmy’s childhood friends and neighbours are being priced out. To her, Laru Beya is the way to make her voice heard for the community she loves, and a place which needs support to continue being a home for people like her.

“I think Laru Beya is a strong voice in our community,” she says. “If they weren’t here, who would give these kids a chance? Things are changing and one opportunity can change a person’s life, especially a child who’s still figuring themselves out. Laru Beya is a safe space for folks of colour. It’s us taking up space.”

Credits

Photography Jeano Edwards

Fashion Milton Dixon III

Make-up Dan Duran at Frank Reps using Gucci Beauty

Photography assistance Julius Frazer

Fashion assistance Olaoluwa Olajide and Hannah Atira

Production Mish Parti at Fete Production

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING

Casting assistance Alexandra Antonova

Models Farmata Dia and Ahmed Dia at The Society, DeVaughn Bullock-Wireback and Cristina Wright