Ahead of his m.A.A.d exhibition’s opening at MOCA and the unveiling of her piece in the New Museum’s 2015 Triennial earlier this year, director Kahlil Joseph enthusiastically recommended I explore his fellow LA-based artist and filmmaker Martine Syms‘ work. Martine has already produced a prolific body of work, as well as lectured at Yale, SXSW, and MoMA PS1. Whether penning her Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto or compiling three years of her Google search terms as a diary on everythingiveeverwantedtoknow.com, Martine uses publishing, video, and performance to explore the ways we frame our individual and collective identities by challenging what and how we remember.

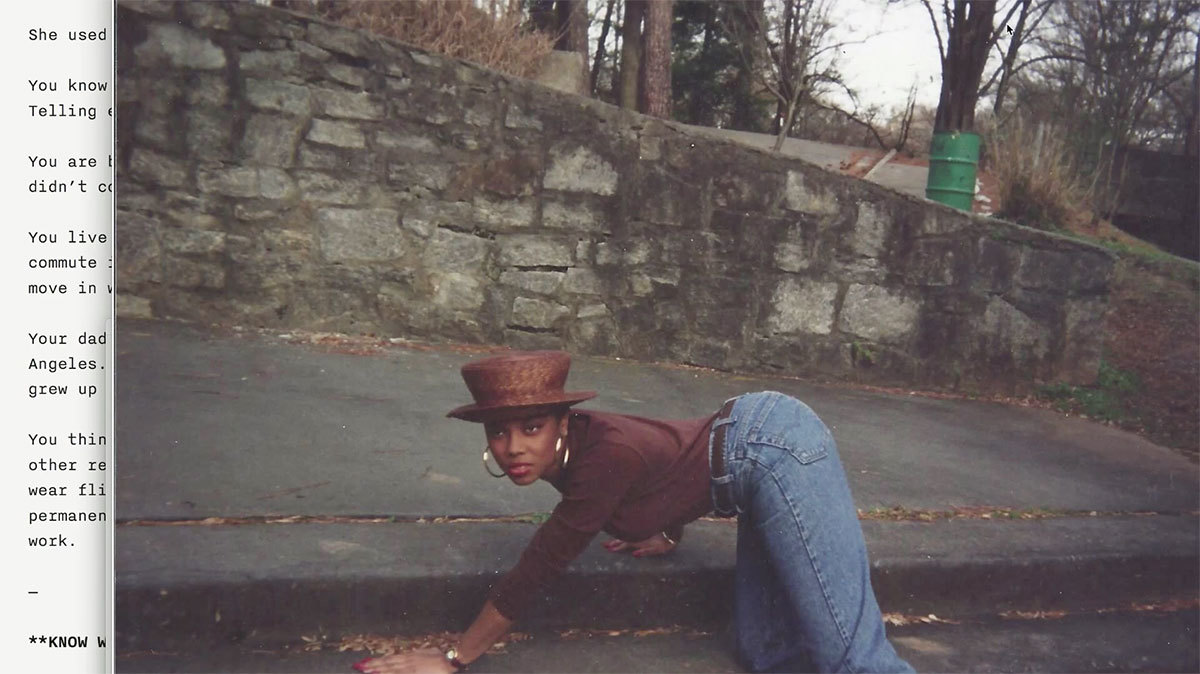

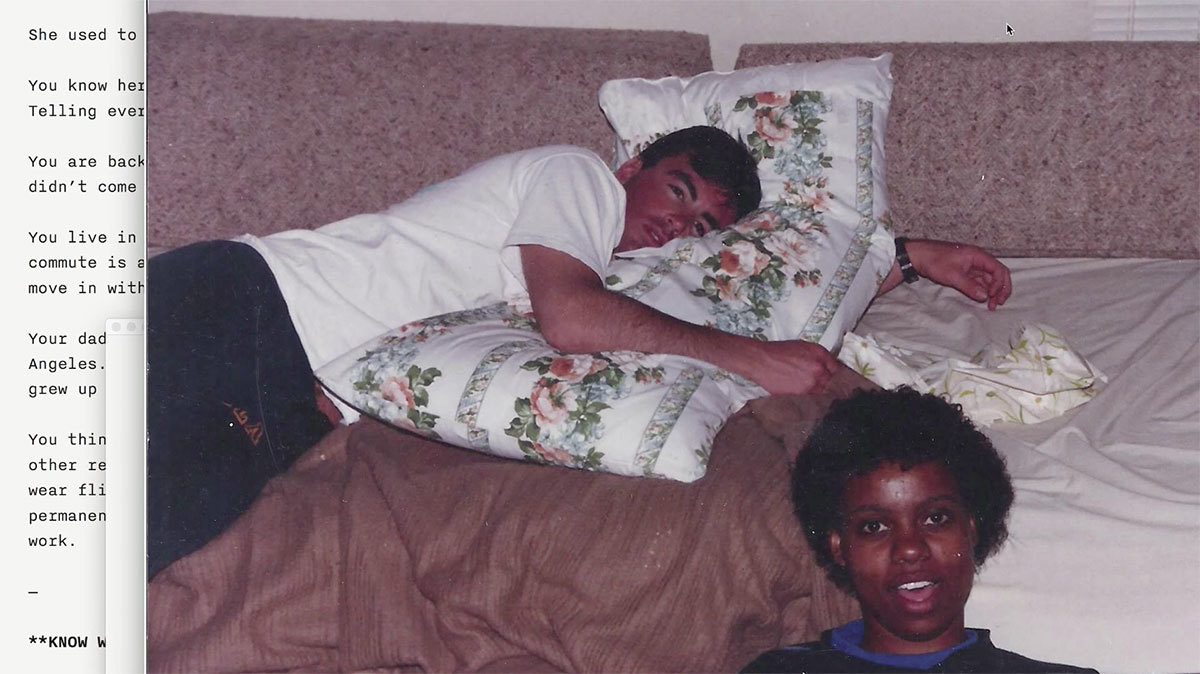

We’re proud to exclusively premiere Memory Palace, Joseph and Syms’ collaborative film commission for MOCAtv. While the short depicts singer/songwriter Alice Smith’s discovery of a photo album, the film’s flickering memories are deeply rooted in Martine’s own. We caught up with the artist to find out how raiding her aunt’s boarding house for old soul vinyl inspired the intimate and beautiful piece.

What are some themes or ideas that consistently interest you?

In general, I’m interested in the way we make meaning within a culture. Whether that’s through television or other kinds of popular media, the ways we come to frame our identities really interest me. I like to explore how personal histories intertwine with social histories, and examine the ways we look at femininity or blackness or even regional identities–I’m actually making a piece about California right now. What are the historical, economic, or social frames that help us make meaning?

A few years back, you presented your Reading Trayvon Martin project at The New Museum. Have you thought about expanding it to include events since then?

readingtrayvonmartin.com is a personal bibliography full of articles I have read about the Trayvon Martin case. It’s ongoing, although it’s definitely slowed down. After Trayvon Martin was murdered, I was following the response and subsequent criminal case closely. I saw it picked up both in mainstream media and on Twitter, and was interested in how the story shifted through the media.

The way the website is designed, it strips a lot of the information but leaves the titles so it’s only working with the language of the headlines. It goes through tweets, primary documents, articles, videos, anything that I was encountering and thinking about my own position as a reader–when I was the presumed reader, when I wasn’t, and what the difference between those kinds of stories were. Now, I think it tells a kind of meta story about how it gets pushed out of the news, but at the time, I was just immediately trying to find information. My initial motivation to make the piece was ‘Where can I find a place to put everything that I’ve been reading in one place, so that if someone wanted to read about this they could?’

When that case was going on, I felt it was maybe for someone my age, was one of those big, important civil rights occurrences. It brought a lot of attention and wider visibility to what’s going on in the criminal justice system, biases, the safety of black bodies, and the double standard of the law–which, if you’re black, you already knew about! But since it was a very specific response, I haven’t really thought about expanding it to involve current cases or making new sites around them.

Memory Palace deals with amassing information as well, but seems to work with an existing archive rather than creating one. Can you tell us more about the video and how you and Kahlil came to collaborate on it?

My aunt had a boarding house in LA that had been in our family for a while. There were all these different people living there and it’s where we spent many holidays when I was a child. My dad lived there when he’d first moved to LA, and my brothers and I have all lived there as well at different points, so it was this big nexus for my family.

When I met Kahlil, the house was being sold, so I was going there and taking photos, objects, and old magazines to my studio. I use a lot of those kinds of found materials in my work–one exhibition I did, The Queen’s English, was a collection of books from the bibliography of another book I’d found called Black Lesbians–and I wanted to do something about place and story. Kahlil coincidentally also collects found snapshots, primarily of black families. I was showing him some of the things I got at the house, which included seven boxes of independent soul 7” records. We were just hanging out and every week, I had more and more stuff. He started showing me the photos that he was taking, and we were just sort of messing around and talking about stories that were behind these photos, so it made sense to use those photos to start to tell a story. Memory Palace is really thinking about that house and some of my memories and my family’s memories there, but conflating those with our collective found materials.

Kahlil’s exhibition is up at MOCA until August, but do you have any plans to push these ideas further?

I have a solo show opening at Bridget Donohue Gallery in New York this September. The show is more or less a kind of deconstructed film, and it’ll operate using a similar character to the person who’s explored in Memory Palace.

martinesyms.com

@MOCAlosangeles

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Martine Syms and Kahlil Joseph, stills from the video Memory Palace, 2015, courtesy of the artist and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles